It’s the summer of 1986 and rock is down the toilet. Not heavy metal (Iron Maiden are at their peak and Metallica are poised to overtake them), but good old-fashioned rock’n’roll, the kind pretty girls like too. You know, low-slung, sexy, catchy and, above all, c-o-o-l. Clad in stressed leather and daubed with morning-after make-up. Crotch-hugging, ass-shaking rock.

Oh, there is Bon Jovi, but they’re like a boy band: fake smiles, poodle-haired, formulaic rock-by-numbers pretenders. Rock for people who don’t actually like rock; pop in rock clothing.

So what can a poor boy do, except to go home and sit in a darkened room playing with knives? Make like Mötley Crüe is somehow real? Or Poison? Come on, man.

A year later, things would begin to change drastically with the arrival of Guns N’ Roses, straight from the streets of Hollyweird, blitzed on neon and permanent midnight. But it would take time for their impact to fully unload.

First though, came a British band that would score a gargantuan hit straight out of the box. A group of fuck-’em-all braves who showed true vision, real courage, ultra-panache by shaking off their shiny punk-pop skin to reveal the kind of snake-hipped, tra-la-la, riff-addicted rock we hadn’t seen since before Bonzo left the planet.

They were The Cult, and they were hated as much as they were ever loved and they knew it and just didn’t care. And in 1987 they would become the unlikely saviours of rock – real tattooed moonchild rock – with the release of their third album, Electric.

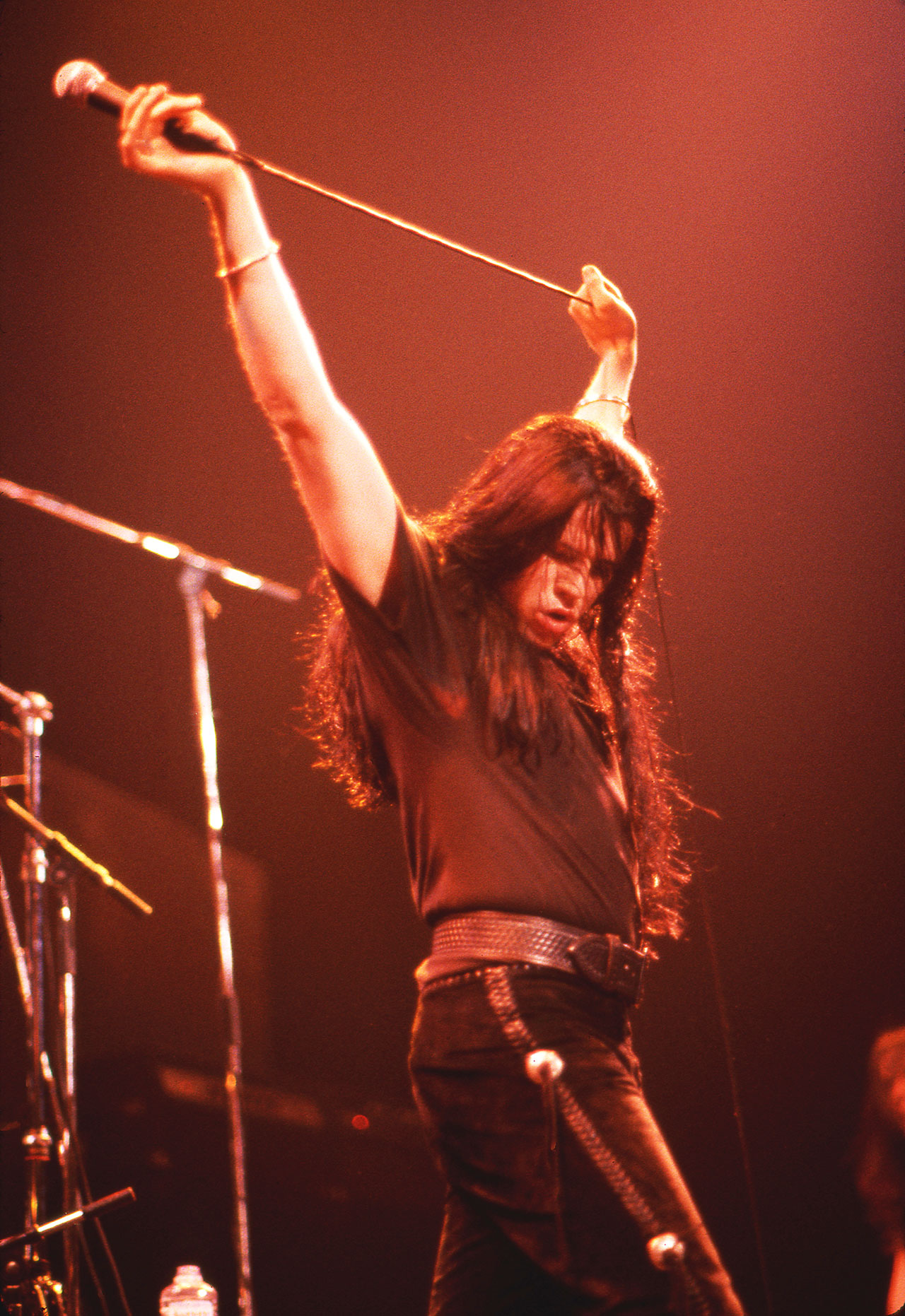

“It was just such an exhilarating time. The energy still resonates for me,” singer Ian Astbury reflected in 2013. “We didn’t have any conscious intentions to objectify the music. It was pure instinct.”

In fact, the recording of Electric was full of conscious intention. As bassist Jamie Stewart says now, Hendrix, Cream, Zeppelin, AC/DC, the Stones, “they were all in there, yeah. It was an intentional step… Ian had completely lost interest in British post-punk things. He just wanted to do straight-out rock.”

For those who didn’t live through it, it’s impossible now to imagine how unthinkable, wrongheaded even, it was for a British band in the mid-80s to simply want to rock. With the weekly music press still dominated by the fiercely partisan NME, where the term ‘rock’ could only be viewed in quotation marks while held aloft with a pair of tweezers, even having long unreconstructed hair was considered deeply suspect.

But then Ian Astbury had always been seen as somewhat suspect to the privileged elite of the UK music press. Never mind that his first group, Southern Death Cult, a four-piece formed in Bradford in 1981, were a basic mesh of goth and punk which found the singer dancing as if round a totem pole in Bowie-red hair. Later he shaved it into a mock-Mohican, his band sounding closer to Siouxsie And The Banshees than to AC/DC. But no matter how much they shook they were never quite hip.

From Bradford, via Ontario, Glasgow, Liverpool, a stint in the army, and a crash course in brain surgery when he heard The Doors’ The End while watching Apocalypse Now, which he described as “a religious experience”, 19-year-old Ian Astbury was not your run-of-the mill panda-eyed goth. Born to rock, to be wild, to show off and steal your girlfriend, he was frontman gold. Yet one hilariously pretentious Paul Morley article in the NME aside, Southern Death Cult remained of niche interest. A cult without a cause.

Then came Death Cult, formed in 1983 by Astbury and former Theatre Of Hate members guitarist Billy Duffy and drummer Nigel Preston, soon to be joined on bass by Jamie Stewart – “I was a guitarist who converted to bass just so’s I could join Death Cult.”

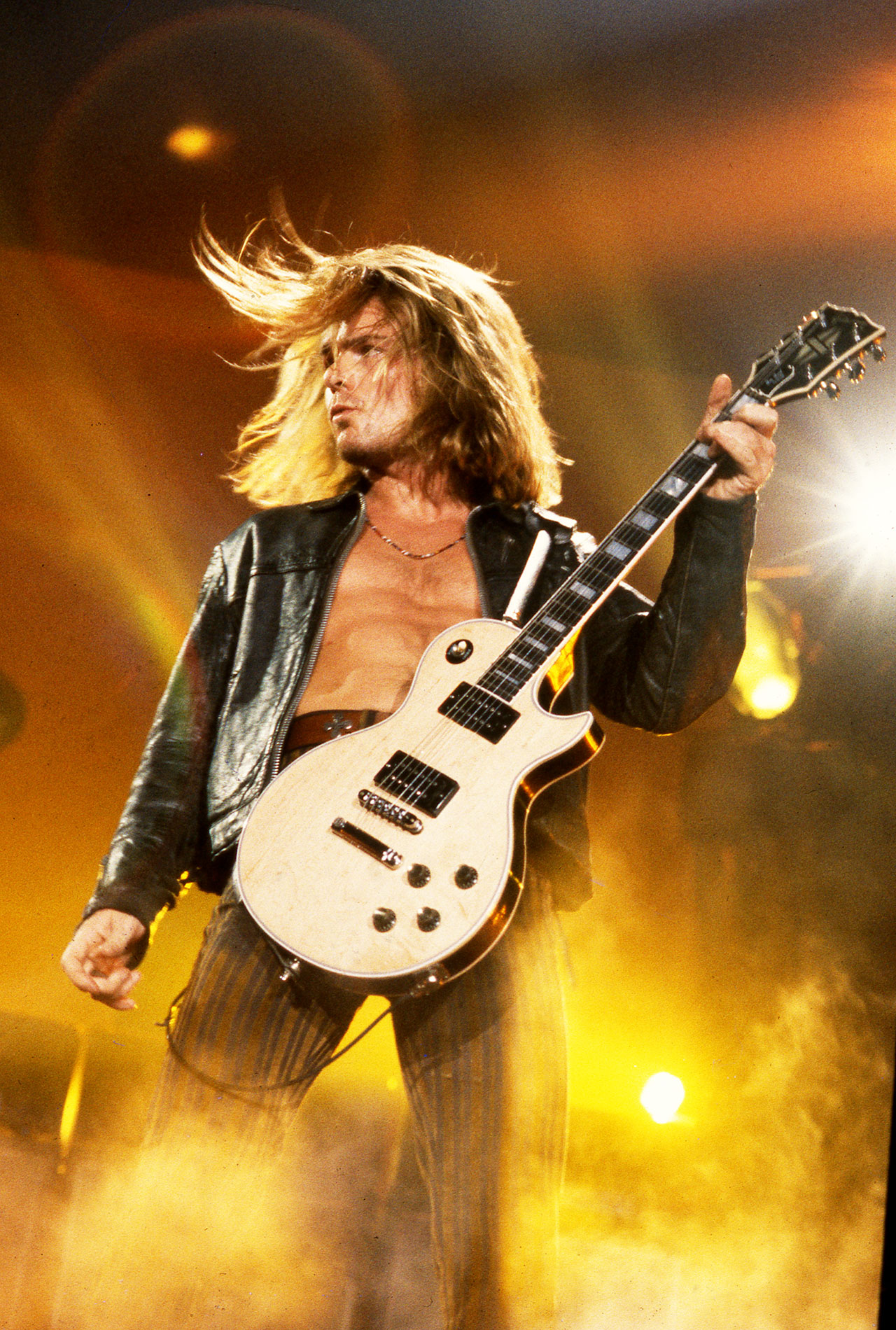

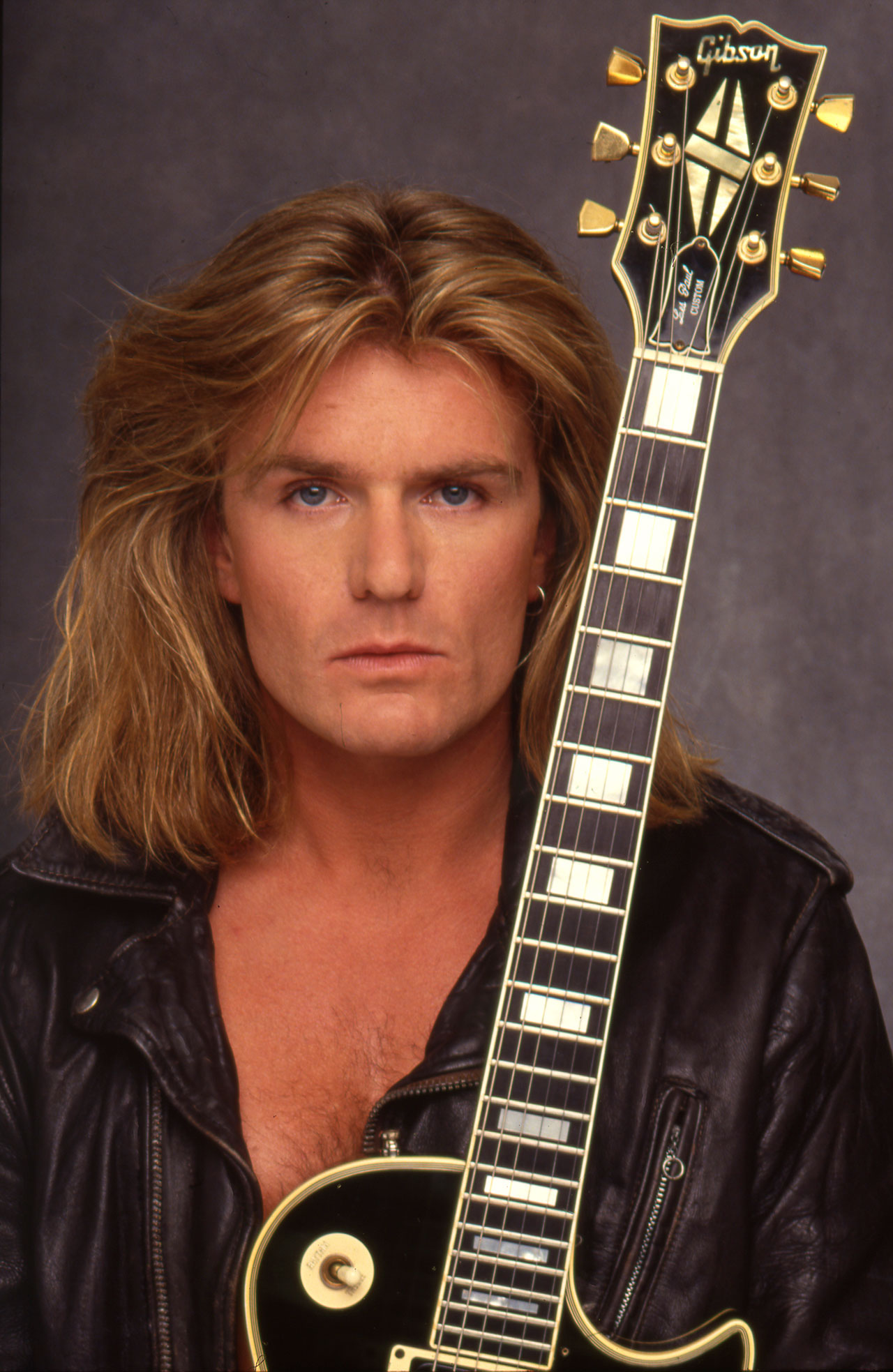

From day one, the leaders of the band were always Astbury and Duffy. The latter was from Manchester and of royal punk lineage, having been in The Nosebleeds when they featured a squirmy, painfully self-conscious singer named Steven Morrissey, later of The Smiths. Then Theatre Of Hate, whose debut album was produced by Mick Jones of The Clash. You questioned the moody-looking Duffy’s punk credentials at your peril, yet the first gig he’d gone to was to see Queen at Manchester’s Palace Theatre in 1974.

“It was a black stage, the guitar was chugging a D chord, which I’ve ripped off a million times, and Freddie Mercury appeared in some window with just his face visible,” Duffy recalls on his website. “Then, when the song kicked in, every light on the stage lit up. The entire band was dressed in white, and Brian May had a cape. That experience, which is utterly indelibly printed in my mind, made me realise I wanted to do that for a living.”

A deal with up-and-coming London indie label Beggars Banquet resulted in a four-track EP that sounded as earnest and pure and as bleak – more pre-hits Adam Ant than peak-time Led Zeppelin – as the band’s name.

“The music we made back then was much more complicated than what we were doing by the time we came to Electric,” recalls Stewart. “There was a lot more to do on the bass, the guitar didn’t figure as much. As time went on, though, things got simpler and simpler, to where on Electric it was all about the guitar, and I was basically just strumming a D chord.”

The process of stripping back the post-punk pretensions began with the final shortening of the name, in 1984, to simply The Cult. Indeed the real roots of what was to come on Electric were there on The Cult’s first album, Dreamtime. The nod to Astbury’s obsession with The Doors, and their track Horse Latitude, on album opener Horse Nation; the big, pounding drums and atmospheric sky tracing of Duffy’s guitars; the trippy lyrics – ‘Let the children kiss the stars,’ Astbury sighs on the single, Spiritwalking.

It was clear that Astbury saw himself as a direct descendent of rock’s golden age, the late-60s. ‘I will wear my hair long,’ he threatened on the title track, ‘an extension of my heart’. “It was just as a protest,” says Stewart now. “This is a post-punk band saying, well, we’re gonna do it our way, thanks.”

They certainly looked like nobody else at the time. Performing on Channel 4’s The Tube that year, while Duffy stands remote, shoe polish-black hair, tied at the back, and shiny black leather trousers, Astbury is a constellation of colour, his face divided down the zigzagged middle, white pancake with red flag stripes, his hair similarly duochrome, black at the front, white gold at the back. His next TV appearance later the same year found him wearing flared, bell-bottom trousers – a hanging offense in 1985. The album recorded only modest sales, but warrants were now officially out for his arrest by the fashion police.

Then, in October ’85, came their second album Love, their big, chart breakthrough. The sound of Love was the sound of The Cult in excelsis. Reverb-heavy, lightning-flash drama, gothic, psychedelic, pop-to-punk-to-rock moreish. Nevertheless, says Stewart, “The initial reviews of Love were just dreadful”. Thankfully their growing fan base of sad-eyed boys and kohl-eyed girls loved it. But it was the newcomers, the Cult-curious, who made the album and the three singles released from it – She Sells Sanctuary, Rain, and Revolution – significant chart hits.

Overseen by London-based producer Steve Brown, fresh from fashioning hits for ABC and Wham!, but who’d cut his teeth as an engineer in the 70s with Thin Lizzy, Dire Straits and the Boomtown Rats, Love was the place where The Cult met their future full-on. Or so it seemed. “Up until Love we were just trying to get our influences out,” says Stewart. “Now we were more ourselves.”

Perfect band meets perfect producer, makes perfect album for imperfect times. By the summer of 1986, when the Love tour was over, Beggars Banquet were understandably eager to get band and producer together to do it all again, only this time even better. Time was booked at Richard Branson’s plush Manor residential studios in the Oxfordshire countryside, and budget levels were set at an appropriately eye-watering high. Nothing, surely, could go wrong. Love would be followed by an album called… Peace. Geddit? The Cult finally had the force with them.

“It started out as exciting,” says Stewart. “We were coming off a success so we were like, okay, let’s go and see if we can repeat that success: Love Mk II. The riffs and the chords were pretty much in that vein.”

Three months later, however, when the recording was complete, it became obvious to them all, says Stewart, “that it was just… overblown. Overcooked. At the time, I was trying to like it, but I played it to a few people and I thought: ‘All these tracks are too long and there’s an awful lot going on in them.’ But it takes a lot of bottle and commitment to give that up and say right now, we’re not going to release this, we’re gonna do something completely different.”

In fact it was Astbury’s obvious lack of commitment that finally condemned the Manor sessions, as they became known. “They were very unprepared,” recalls Steve Brown. Astbury, in particular, he insists, was “extremely unprepared”. On Love there had been an intense pre-production period at a residential rehearsal studio, working on the material. “It encouraged a team spirit. I’d go and see Ian in the evening and we’d go over lyrics and stuff. But we were all thrown into the Manor sessions… It was a very different atmosphere.”

The material just wasn’t there in the way it had been on the Love album, says Brown. “We hadn’t had any pre-production. I had a few scratchy demos, and we were just recording without rehearsing, which I’m really not comfortable with at all. One of my sayings is: measure twice, cut once.”

But there was “another element” to his unease. “I think Ian was drifting across the Atlantic, mind-wise. I don’t think he was interested in going away to Richard Branson’s mansion house to record a British album. I think somebody was on the other side of the Atlantic in New York, studying graffiti and rock’n’roll and AC/DC and all that sort of thing. If I’d have had the guts, and the age, maybe, I’d have put the brakes on the whole album and gone to the record company and said: ‘No, we’re not there. We need to go and get the material together and do some pre-production.’

"However, the world doesn’t work like that. They’ve got audiences out there gagging for another album. But the vibe wasn’t there. We weren’t coming up with the Sanctuarys or the Rains or the Revolutions. They just weren’t appearing.”

Though he declines to name names, it’s clear that “other element” Brown points to was American producer Rick Rubin. A large man in billowing shirts and khaki camouflage trousers, with his enormous scraggly beard and trademark wraparound shades, these days Rick Rubin resembles a hippie-ish Orson Welles, and certainly there is something of the musical auteur about him.

Rubin likes to go barefoot to meetings, espouses a Zen philosophy of vegetarianism and karmic law, and fingers a string of lapis lazuli Buddhist prayer beads as he talks, closing his eyes and rocking silently back and forth as he listens intently to music, before pronouncing gnomic judgement. His voice is surprisingly soft and always reassuring, and many of the artists he has worked with over the past 30 years refer to him simply as The Guru.

But that all came after he worked with The Cult. Back then he was a 23-year-old chancer from Lido Beach, on Long Island, who still ate pizza and burgers, though didn’t drink. Music had been his passion for as long as Rubin could remember. Interestingly, considering the career he was to have, he loved The Beatles but “never really liked the Stones”.

“I have no training, no technical skill,” Rubin insisted, although he could play guitar and plainly knew his way around a recording studio, “it’s only this ability to listen and try to coach the artist to be the best they can from the perspective of a fan.”

At the time he began working with The Cult, he had already produced career-defining albums for The Beastie Boys (Licensed To Ill), LL Cool J (I Need A Beat), and, most recently, Reign In Blood for Slayer. He’d also produced Walk This Way, the first major rock-rap crossover hit, for Run DMC and Aerosmith.

He was also a devoted AC/DC fan. “I was in the studio in New York one time and Rubin was in the next studio, sitting there with all these AC/DC albums on the desk in front of him, using them to make sure he’d got the drums and guitar right,” recalls former AC/DC producer Tony Platt. “They were like his template for the future.”

As Rubin later recalled: “When I’m producing a rock band, I try to create albums that sound as powerful as Highway To Hell. Whether it’s The Cult or the Red Hot Chili Peppers, I apply the same basic formula: keep it sparse, make the guitar parts more rhythmic. It sounds simple, but what AC/DC did is almost impossible to duplicate.”

But that didn’t stop him trying.

Jamie Stewart recalls that it was Astbury who was the main driver in abandoning the Peace album – and with it the services of Steve Brown – and relocating the band to Electric Lady studios in New York to start all over again with Rick Rubin.

Brown recalls: “I received a phone call to give me the news that they had decided to go off to New York and record with Rick Rubin.” The band had also sacked their UK management team and signed with Frontier, a powerful LA-based company. “So you can see a clear break right there. See somebody’s gone: ‘Right, let’s go take America. And we don’t want to do it as a British band we want to do it as a pseudo American band.’”

The vibes just weren’t right, says Stewart. “Ian’s into vibe. Ian would much rather record where the Stones recorded something famous, like Olympic studios in London. Ian had moved on. He’d gone back to listening to more blues – and the Beastie Boys,” whose Fight For Your Right, a hit at the time, found Rubin stealing from AC/DC’s High Voltage for the riff. “Ian just lost interest in the reverb, echo, big wall of noise thing we’d had on Love. He’d lost interest in it almost before we’d started recording, and got even less interested in it as we went along.”

All but four of the tracks that ended up on Electric – including a horribly plodding cover of Steppenwolf’s Born To Be Wild, the only bum note – had originally been recorded at the Manor. Only one of the four, Lil’ Devil, with its AC/DC-on-stilts riff and hot-lips Jagger lyrics, had real impact though, giving the band their biggest hit single in Britain yet. The other seven were remade-remodelled by Rubin.

“There were some great guitar riffs that were in the [Peace] sessions that got lost in the [Electric] sessions because of the complete turnaround sound shift,” says Stewart. “I’m thinking of Electric Ocean and the first version of Love Removal Machine. It was almost baby with the bath water, but we just had to do it.”

Indeed the Peace version of Electric Ocean had a groovy, spiralling 360 riff that is completely missing from the more juddering Electric version. Love Removal Machine had the same ‘borrowed’ riff from the Stones’ Start Me Up as on Peace, but was shorter, more manicured, right down to its new finale, another ‘borrowed’ moment, this time from Zeppelin’s Heartbreaker – that glorious 90 seconds at the end where Page ditches the intricacies and simply rocks the fuck out. Another cornerstone Electric track, Aphrodisiac Jacket, with its horny, descending riff, unashamedly evokes Cream’s Tales Of Brave Ulysses.

The most glaring appropriation of a classic rock guitar riff, though, comes on the lead track, Wild Flower: an exact replica of the riff to Rock ‘N’ Roll Singer by AC/DC. “There was a lot of AC/DC going on at the time, it’s true,” Stewart says with a laugh. “It was on in the studio a fair bit. Like, this is more the sound we’re going for now. Trying to acclimatise to this new soundscape where the rhythm guitar is often the riff.”

It’s not like AC/DC or Zeppelin or the Stones didn’t ever ‘borrow’ from others. “Billy told me some years ago he’d talked to Angus Young about that riff [to Wild Flower] and apologised, and Angus said: ‘Don’t worry about it. We all borrow stuff all the time.’”

Across the street from Electric Lady’s funky Greenwich Village location was a retro rock memorabilia store called Rock And Roll Heaven, where Astbury would spend hours entranced by its collection of 60s and 70s American music mags, buying up vintage psychedelic posters by Rick Griffin and hard-to-find vinyl LPs. “It was a holy grail of this period we were enamoured with,” he recalled years later in Rolling Stone. “We’d take these artifacts back to the studio, like, ‘Check out this picture of Jimmy Page in Creem magazine from 1975!’ We even had ‘Zoso’ T-shirts made up.”

Rubin also had another trick. At the same time as beseeching them to abandon their “pussy English music” in favour of rock with a capital ‘R’, he brought his experience as a hip-hop producer to bear. Specifically, the instant gratification a monumental kick-drum guarantees.

Drummer Les Warner, who was making his first album with The Cult, was a super-talented player whose idol growing up had been Thin Lizzy’s Brian Downey. Percussive, clever, powerful, he was into the sheer dynamics of drumming. When Rubin insisted he rein it in for a far simpler backbeat that recalled AC/DC’s workmanlike drummer Phil Rudd, Warner was appalled.

But then Duffy had also been directed to flush the flash and concentrate on non-effects, hard-edged rhythm, so Warner reluctantly went along. The end, though, more than justified the means. Rubin recalled how he would wait for his engineer to finish playing back a mix, allow the band to make their observations, “and then I’d push the kick-drum up five decibels. That’s what ended up on the record – ridiculous kick-drum!”

And total attitude. Everything was done old-school, recording drums, bass and guitar all together live in the studio. “No cutting and pasting. Just for the vibe, the live attitude thing. But it’s hard. That’s quite a discipline.”

With work in New York continuing right through Christmas 1986, when Astbury and Duffy returned home to England in the New Year they looked ahead emboldened, to a 1987 loaded with 50-state dreams and a stars-and-stripes future.

Stewart feels “Billy and Rick were the main drivers” for wanting Electric to be The Cult’s ticket to ride in America. “Billy’s always been a business head, and I’m sure Rick had his finger on that too,” he says laughingly. “So if you wanna make a record that people outside of LA and New York are gonna buy, you have to ditch the chorus reverb and… I don’t know. You’ve got to change your guitar amp.”

Released in March 1987, Electric divided everyone. The hard rock mags acted suspicious, like what are these punks trying to pull? The new wave bibles also smelled a rat, for different reasons. Even some of the band’s fans were frankly baffled. Instead of the sparkly fairy dust of Love, there were now tightly compressed guitar riffs. The kind of high, dry, blam-blam sound that sounds great bursting out of tiny radio speakers. Or cheap stereos, straight out the window, delighting the neighbours.

“We lost a lot of the British, kind of goth audience at the time, but we still kept a bunch,” says Stewart. “Maybe half of the Mission fans and people that liked that kind of thing went: ‘This Electric stuff is not for us’. But half of the folk who did like Love could also get on with Electric, despite it being quite a shift. You weren’t supposed to do that and yet we did.”

In America there was also a hasty rethink among their existing supporters. “College radio, who were all over Love, weren’t quite as all over Electric. But then there were tons of classic rock stations in the States who would have been up for it. But then somehow or other in Britain it took off as well.”

As with Love, there were three hit singles on Electric – Love Removal Machine, Wild Flower and Lil’ Devil – only this time they also began climbing the US charts. Like Love, Electric also got to No.4 in the UK. Unlike Love, Electric also reached the US Top 40, eventually selling more than a million copies there. By the end of 1987, as the world tour that followed finally came to an end, The Cult had proved their doubters wrong, and drawn a road map for all who would now follow, not least Guns N’ Roses, who opened for the band on the North American leg of the summer ’87 tour, after being invited on to the tour personally by Ian Astbury.

Speaking three decades later, Billy Duffy put it like this: “We heralded a change that culminated with everyone buying Appetite For Destruction, and we were treated badly for standing up and saying there’s nothing wrong with organic rock music. Ian wears his heart on his sleeve, and he shows where he’s at in his dress. We were into heavy rock but we weren’t a metal band, and the English music press felt scared by that. They didn’t have a clue what we were doing.”

On tour, Duffy suggested they needed a second guitar player to play Electric material live. So Jamie moved over and former Zodiac Mindwarp bassist Kid Chaos came in. “It was hard to find somebody else, because we weren’t in the Whitesnake camp and we weren’t in the punk camp any more,” explains Stewart. “We needed someone in tune with The Cult, and that wasn’t going to be easy.”

They were on the road, hitting the sky, for eight months. By the end of it the band was almost finished. “There were no drugs, that was never really our thing,” says Stewart. “Ian liked wine and Billy liked Jack Daniel’s. Then somebody decided smashing gear would be a good idea, and that was the beginning of the end, really.”

When, on the last night of their Australian tour, Kid Chaos “gave away his bass amp to some kid in the audience”, it was the last straw.

Back home for Christmas 1987, a year exactly since they’d finished working with Rick Rubin on Electric, The Cult didn’t know what they wanted anymore, just what they didn’t want. Warner was fired soon after. Kid Chaos went back to Zody. Astbury, Duffy and Stewart “fled from each other, really”, and The Cult went into forced abeyance for nearly nine months, when they began work on the next step towards American superstardom, with Canadian producer Bob Rock, with whom they would make the multi-platinum, planet-quaking Sonic Temple album. After that, Guns N’ Roses stole their new drummer Matt Sorum to help them make the two Use Your Illusion albums, and Metallica made off with Bob Rock to record their own shape-shifting mega-hit, the Black album.

It was with the Electric album, though, that the real rock revolution began. Standing on the shoulders of giants like Zeppelin, AC/DC and the Stones as they churned out one drop-dead-gorgeous classic after another. The kind of album the then recently rejuvenated Aerosmith could still only dream of making. The one that sent the jolts that fried your wolf-child, sweet honey baby brains. Right on.