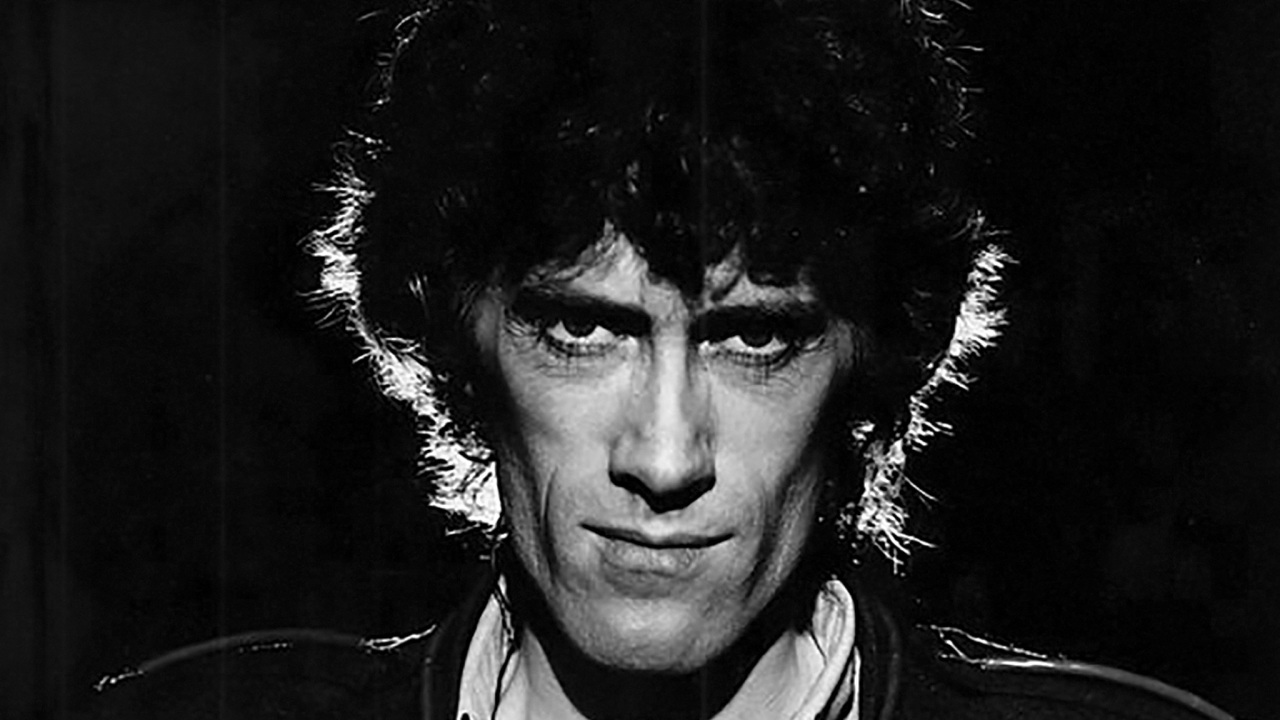

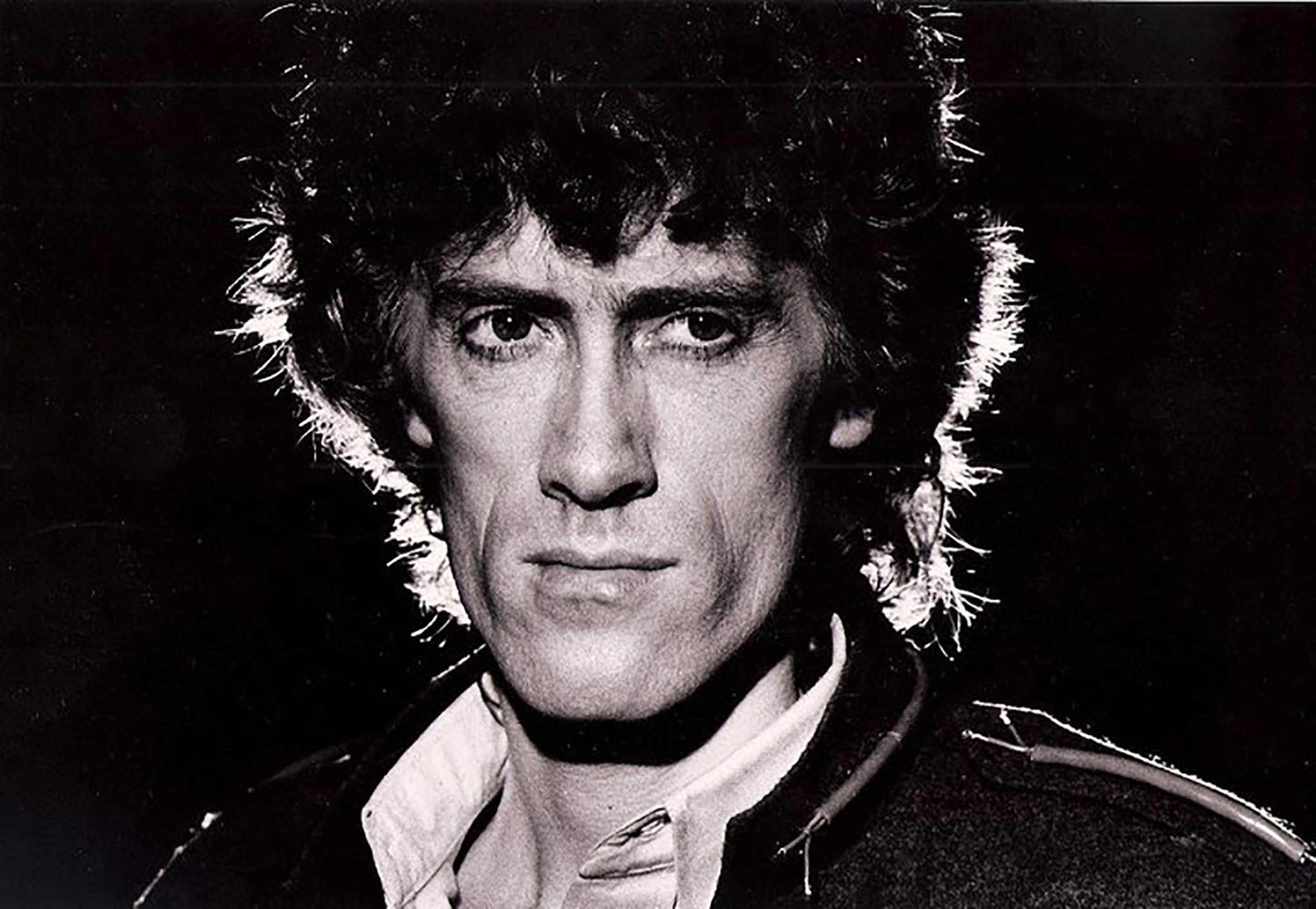

Rupert Hine is one of the few prog rockers – even one of the few at the outer limits of prog – to have had a five-decade career, a Top 5 novelty hit single, been in a band with an alternative comedian, and produced artists as wide-ranging as Camel and Rush, techno pioneers Underworld and Doctor Who Jon Pertwee. He’s earned accolades from Sir George Martin, and received comparisons to the maverick UK greats: Peter Hammill, Peter Gabriel, David Bowie, Bill Nelson, John Foxx and Kevin Ayers, to name but a few.

“I remember buying his adventurous 1980s trilogy of albums at the time of their release,” reveals Tim Bowness. “I discovered him via an interview in Sounds, which compared his work to musicians I liked such as Peter Gabriel and Peter Hammill. At the time there were very few artists producing the sort of music Rupert and his engineer Stephen W Tayler were coming up with. The nearest comparisons were Gabriel’s 3 and 4, Hammill’s A Black Box, Kate Bush’s The Dreaming and, at a push, Bill Nelson’s Quit Dreaming And Get On The Beam.”

He was a mid-60s mod, a late-60s hippie, an early-70s quirky glamster, a mid-70s prog jazz-rocker and an 80s avant-popster. He’s a regular musical Zelig.

“Zelig? I like that,” says Hine of Woody Allen’s fictional character who morphed throughout history depending on the company he kept, and the context. He also likes Prog’s other catch-all term for him. “Eccentric British songcraft? That’s good too.

“I was 16 when I made my first record, in 1965, and here we are 50 years later, still going,” he reflects with a wry chuckle. “I have favourite periods but they were all different. I can’t ever stand still. I’ve always admired people liked David Bowie who go from album to album, changing style, if not genre. You get an amazingly high turnover of fans and it can be dangerous, but I like the idea of evolving. I can’t not. I’m not stuck in the 60s or 70s.”

PHOTO ABOVE: GETTY

It was at school in Horsham, Surrey in the early 60s that Hine formed his first band, a “traditional R&B beat group” called The Aztecs in which he assumed vocal and harmonica duties. They later changed their name to 4 7⁄8 (four and seven-eighths), their imagery based on that of a building society. After school, at Ewell Technical College, came Randy’s Incaras, where Hine met David MacIver.

The pair, fearing the end was nigh for beat groups, decided to form a folk duo, Rupert & David, à la Simon & Garfunkel. Gigs alongside Bert Jansch, Leonard Cohen, Donovan and Paul Simon himself became commonplace. In 1965, they recorded a version of The Sound Of Silence for Decca, with young session musician Jimmy Page on guitar, a certain Herbie Flowers on bass, and a 26-piece orchestra arranged by Mike (She’s Leaving Home/Jesus Christ Superstar) Leander.

Careers variously in modelling and acting seemed to briefly beckon for the Swinging 60s dilettante – that was him advertising a Terylene shirt in a TV commercial with Jim (Carry On) Dale – but it was, he says now, “A passing wisp of a moment in time,” that he puts down “partly to the way I looked – a bit Donovan-esque flower child”.

In 1971, he recorded his debut solo album, Pick Up A Bone, with Roger Glover of Deep Purple and with orchestration courtesy of Paul Buckmaster, arranger for Elton John and Bowie. It has become something of a lost cult classic, featuring Hine’s unusual, eclectic approach to songwriting. The 1973 follow-up, Unfinished Picture, was a darker and more experimental affair. Some have even heard in its idiosyncratic textures a prefiguring of Radiohead’s post-rock.

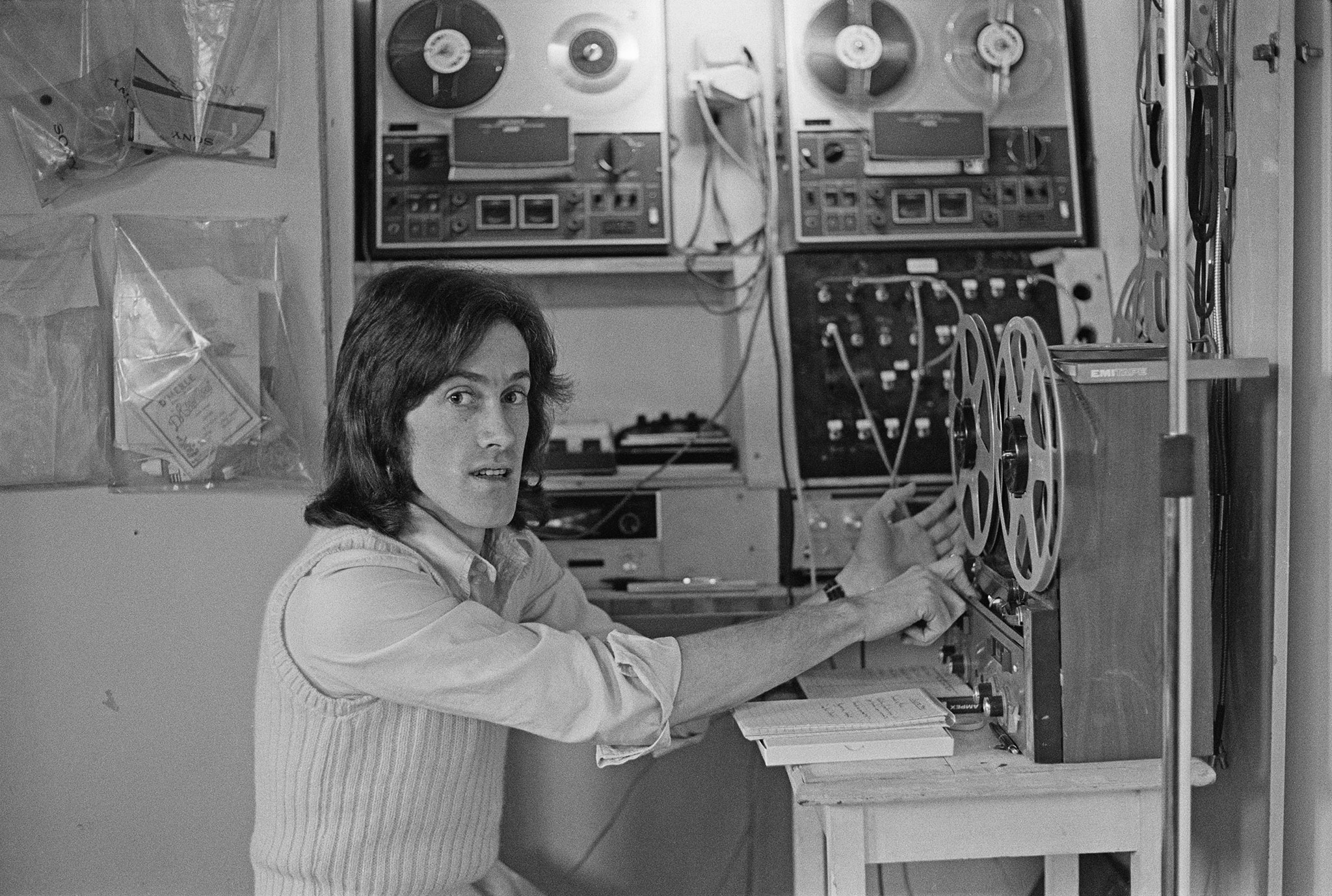

“That first album was very much produced by Roger and it had these amazing arrangements,” he explains. “It was all done at the highest level, at Air Studios, and we had a wonderful time making it. And even though it wasn’t a massive seller, it was well received and the record company wanted me to do another. Trouble was, Deep Purple had become the biggest band on the planet and so Roger couldn’t do it. So he suggested me. He said: ‘Just do the umpteen crazy things you do at home with your mad tape recorders and stuff!’”

Unfinished Picture, with its contributions from Mike (King Crimson) Giles, John G Perry of Caravan, and Steve Nye and Simon Jeffes of Penguin Cafe Orchestra, wasn’t actually Hine’s first production job. That honour goes to the single he made in 1972, entitled Who Is The Doctor, for Jon Pertwee, a danced-up version of the Doctor Who theme with a spoken-word, recitative performance from the Time Lord himself.

“I was asked if I’d do a vaguely disco‑friendly, dance version,” he laughs. “I loved the original theme but I wasn’t sure about the dance bit, but I liked a challenge so I did it. I was a kind of one-man BBC Radiophonic Workshop. It was four-on-the-floor, pre-disco disco. It was great fun.”

It was an inauspicious but suitably eccentric start to Hine’s production career. Before long, he had produced Kevin Ayers’ 1974 album, The Confessions Of Dr Dream And Other Stories, which sold a quarter of a million copies and established Hine as the go-to studio hound.

Did he have tons of state-of-the-art equipment? “It was more tin cans and bits of string than anything particularly hi-tech – it was lo-fi,” he muses, comparing his set-up to that of Mike Oldfield, Mike Ratledge of Soft Machine and early Pink Floyd.

By the late 70s he had produced albums for John G Perry, Dave Greenslade, Café Jacques, Anthony Phillips, Murray Head and Camel.

What, Prog wonders, did those artists demand of him? “My reputation,” he admits, “was that I could produce the unproduceable. Artists that became problematic, the record label would want me to do. Anyone who could be antagonistic. They seemed to think I had this therapeutic technique and could seize a great album out of an artist in a way their confrontations couldn’t.

“Record producing,” he furthers, “is 85 per cent psychotherapy and 15 per cent music. Some artists are very difficult to work with. You’ve just got to get inside them enough to understand why they’re making music. It can’t be because they’re hoping to be rich and famous, but because they have to – those are the artists I’m attracted to. It can be utterly productive one minute and utterly destructive the next, but it’s a wonderful challenge, and when you get it right, it can be tremendously rewarding.”

He means that in the artistic, rather than the financial, sense. Hine has made few, if any, decisions based on commerce. Indeed, he even turned down the offer to produce Def Leppard in the 80s.

“Their manager was so insulted that I said no,” he recalls. “He said, ‘Do you have any idea how much money you’re saying no to?’ I said, ‘Why on earth would that be of interest to me?’”

If Hine has enjoyed any commercial success, it has been accidental. He formed Quantum Jump in 1973 as an opportunity to indulge a penchant for fusion, funk, prog and jazz-rock. Parts of their 1976 debut album sound like 10cc’s brainiac art-rock, or the first foray by Todd Rundgren’s Utopia at their most cosmically intricate and intense, while overall there’s a sense of musicians high on their initial giddy encounter with The Mahavishnu Orchestra.

“I wouldn’t deny that,” he says of the Rundgren connection. “I wasn’t conscious of him at the time, but later on I did recognise a kindred spirit when it comes to a nice bit of musical mayhem. As for Mahavishnu, we all absolutely fell in love with their first two albums. We wanted that intensity, but to combine it with something slightly more vocal. One of the tracks, Alta Loma Road, had a middle section we would jokingly call 45⁄8, it had such a quick time signature.”

Were the performances artificially enhanced? “A little bit,” he reveals. “Nothing too deviant or hardcore. You need to have your chops together to play at that speed.”

As an example of Hine’s “accidental success”, look no further than The Lone Ranger, a track from that debut Quantum Jump album. Reissued in 1979 in slowed-down, ironed-out form, thanks to heavy rotation from Kenny Everett and the inclusion in the intro of the name of a hill in Hawke’s Bay, New Zealand – Taumata-whaka-tangi-hanga-kuayuwo-tamate-aturi-pukaku-piki-maungahoronuku-pokaiawhen-uaka-tana-tahu-mataku-atanganu-akawa-miki-tora, which became its tongue-twistingly infectious refrain – The Lone Ranger became a Top 5 hit. It sold half a million copies and got Quantum Jump on Top Of The Pops, for which performance Hine wore a badge bearing the statement “Creep Is The Word”.

“It wasn’t high-minded at all,” Hine says, recalling his sole Top 5 entry as a professional musician. “It was a fun, throwaway thing. We had no idea it would be a hit.”

Expectations were probably higher for his 80s productions for Tina Turner, Chris De Burgh, Howard Jones, Stevie Nicks, Thompson Twins, Rush and Suzanne Vega. If he was the therapist in the 70s, his producer role in the 80s was as the sonic alchemist.

“In the 80s I was painting pictures with sound,” he says. “My work was considered brave and eccentric and nobody could understand how on earth I was doing it.

“I was organising the recording of noises and sounds from the real world and making them musical,” he says of his rudimentary form of sampling – not for him such luxuries as the Fairlight, although he did consider Dolby and Horn to be contemporaries. “I always loved Thomas’s stuff, and there was a parallel between Trevor and I on the producing front.”

If Horn was Wagnerian, Hine was, he says, “lurking somewhere between Mahler and Stravinsky”. He is especially proud of his work with The Fixx, the British band who became prophets without honour in their own land, yet enjoyed huge success in the States with their Hine‑enhanced attack.

“I came up with an entirely new guitar sound,” he asserts, marking the transition from the traditional “big, heavy, dumpy, lumpy rock guitar sound” to something “far more shiny but no less exciting”. It was a sound mimicked by countless acts. “It had a huge appeal to rock bands,” he marvels. Rush, for example. “Doing The Fixx led to Rush [1989’s Presto and 1991’s Roll The Bones] – they required constant sonic refreshment and they loved The Fixx. Neil Peart also loved the thinking behind my early 80s solo albums and thought that would be good for Rush.”

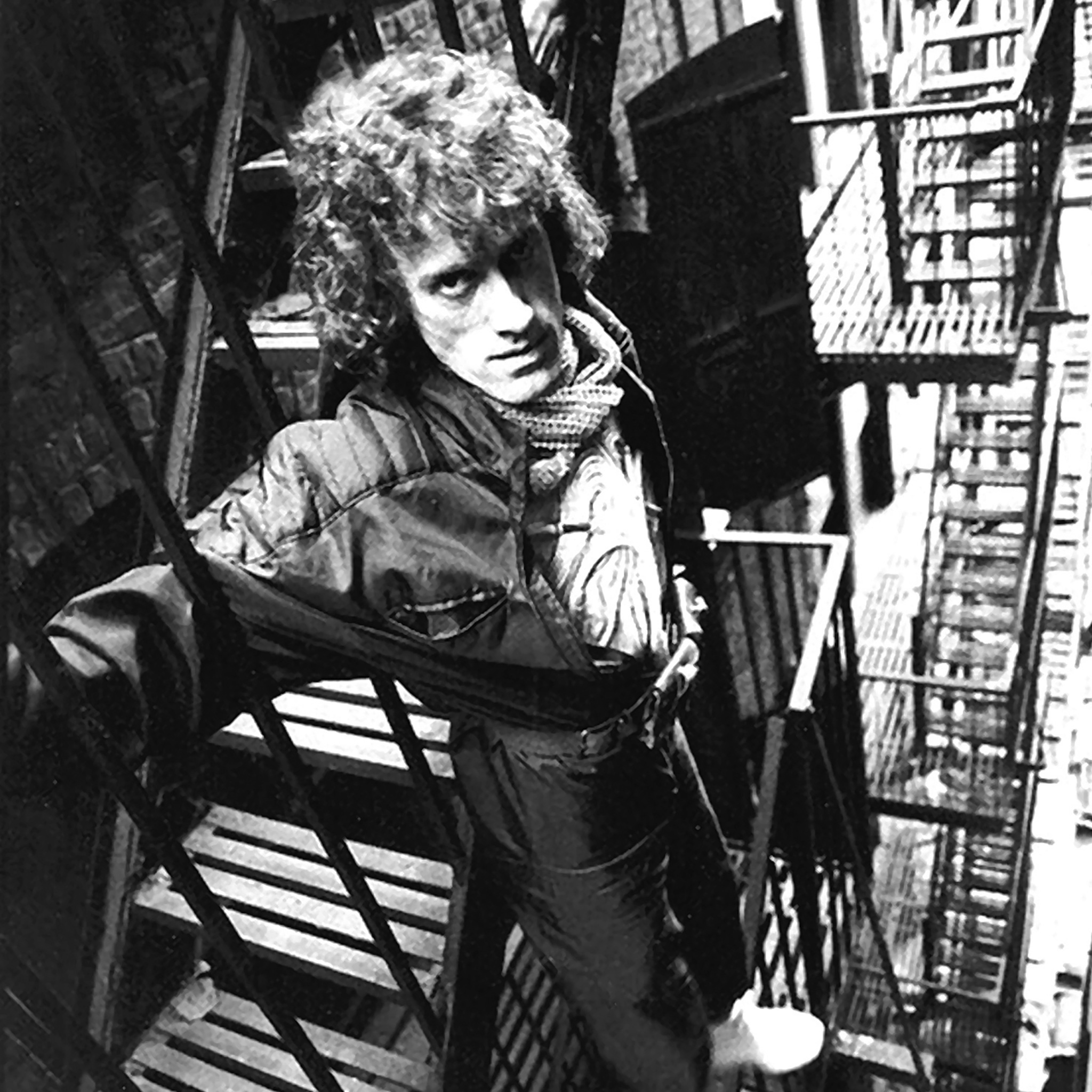

Those early 80s records – Immunity (1981), Waving Not Drowning (1982) and The Wildest Wish To Fly (1983) – formed a trilogy of experimental but obliquely accessible albums, not a million miles removed from Bowie’s Berlin triptych or Robert Fripp’s three-parter (Daryl Hall’s Sacred Songs, Peter Gabriel’s II, his own Exposure). He used them to “say some things, loudly, that were provocative; not simple songs about love but things that mattered to me about the state of the world, undeniable global events that needed commenting on”.

Next, he formed the meta-rock band Thinkman, featuring himself and a series of actors who played the part of musicians, such as Julian Clary. Really, Clary and co were merely the visually appealing front at this, the peak of the video age, for a series of rhythmic/melodic LP excursions by Hine (1986’s The Formula, featuring Stewart Copeland on drums; 1988’s Life Is A Full Time Occupation; and 1990’s Hard Hat Zone).

Hine’s last album proper was 1994’s solo affair, The Deep End. Since then there has been a big-beat/techno project called ARODA that has yet to see the light of day; some soundtrack work; the Spin 1ne 2wo covers outfit with Phil Palmer, Paul Carrack, Steve Ferrone and Tony Levin; and Songs for Tibet: The Art Of Peace (2008) which, during the Beijing Olympics, became iTunes’ third most downloaded album around the globe.

These days, back in England after a decade in California, Hine runs Auditorius, a music publishing project with BMG Rights Management. Having had a quadruple heart bypass operation, he’s not overly fixated on the past: he lives in the present and considers the best music of today to be as good as any ever made.

As for his own contribution, how would he like to be regarded? As the man who reinvented the guitar? As someone who managed to endure and adapt to the changing times? Or as the man who tamed Tina and Stevie and Rush? He considers the bathetic nature of that last sentence.

“That,” he says, laughing all the way from his home in Wiltshire, “was sounding quite saucy until you got to Rush!”

This article originally appeared in issue 58 of Prog Magazine.

YOUR SHOUT

He produced Rush, Camel, Saga and Kevin Ayers. So is Rupert Hine prog?

“He produced two Rush albums which makes him prog enough for me.” - Richard Anderson

“The Quantum Jump albums are prog enough.” - Wayne Roberts

“Has some prog credentials (producing Camel, Anthony Phillips, Rush etc) but a lot of his other work would send most prog fans screaming (Howard Jones, Tina Turner, Chris de Burgh and the like). What I’ve heard of his solo work seems pretty new wave to me.” - Terry Lewis

“He also produced Camel’s I Can See Your House From Here, as well as Worlds Apart and Heads Or Tails by Saga. He also played some synths on Caravan’s For Girls Who Grow Plump In The Night.” - Jordan Ian Farquharson

“His solo albums are what I would class as prog – very talented chap!” - Steven Banks

“One of the most innovative producers and composers ever. How his (solo) work is so overlooked has always perplexed and irked me. Most definitely prog; in the most positive sense.” - Phil Morris

“Decades ago I owned some of his albums. If I think of those I’d rate him a prog enough artist. Have to listen his music again.”- Hannu Jarvenpaa

“Not at all, shouldn’t be even mentioned in the same breath as the word prog.” - Steve Harrison

“The album Waving Not Drowning is outstandingly progressive in my opinion. Ambitious, full of musical journeys, almost every song something new, and trying to move on to another level.” -* Per Per Lundberg*

“Never heard of him. Thought you meant Rupert Holmes for a second.” - Nicholas John Payne

“He likes Pina Colada and that’s good enough for me.” - John Kirtley

“Don’t know about prog but one of the more intellectual members of the music fraternity, incredible sense of humour and way ahead of his time. He was giving anti-homophobia messages in the 70s long before it was fashionable. Check out the video for Lone Ranger.” - Andrew Marlow

“Ten out of ten for name alone…” - Simon Young

“He also produced The Fixx. He is also a recording artist, but I haven’t listened to any of his music. Love his production skills though.” - Chris Pipkins

“He did some great stuff with both Saga and Rush. He also used the Saga guys on his solo albums so he’s prog enough for me.” - Chris Monk

“Produced the best Saga albums and also Chris de Burgh. So the jury is out a bit here.” - Martin Howells