The putrid stench spilled out of the bathroom. It was the smell of decaying flesh mixed with the tang of day-old booze and cigarettes. The maid pushed her cleaning cart through the doorway and squinted into the darkness. It was daytime, but the motel suite’s previous occupant, Keith Moon, had left the curtains drawn, as if concealing the evidence of some heinous crime.

The maid opened the bathroom door gingerly. Her eyes were drawn first to the half-empty tub and then to the puddles of water on the floor. Finally, she saw it – wrapped in sodden toilet paper and placed on the lavatory seat, like the world’s worst birthday present: a dead piranha with its teeth bared in an awful rictus grin.

It was July 1967. The Who were touring America as an opening act for British pop band Herman’s Hermits, and Keith Moon had bought the fish from a local pet shop. That much is true. And the motel was in Vancouver. Or was it Oklahoma City? When it comes to The Who and Keith Moon, myth and hearsay still reign supreme.

Harvey Lisberg, Herman’s Hermits’ manager at the time, was on the tour and remembers the incident – sort of. “A piranha?” he says now. “Oh yes, I heard about the piranha. But I thought there was more than one.”

The Who’s summer ’67 tour was the one in which Keith Moon killed at least one omnivorous freshwater fish, and, if the rumours are true, destroyed a hotel lavatory with explosives and celebrated his 21st birthday by driving a Lincoln Continental into a motel swimming pool. Or did he?

Only one fact remains unchallenged: The Who came to America promising “to leave a wound”. They did just that. They left three months later, after nearly blowing themselves up on live TV. A wounded America would not forget them in a hurry.

I n truth it’s a miracle The Who made it to the US at all. By 1967 they’d already split up twice. Hits including My Generation and Substitute helped get them back together, but intra-band relations remained tense. In one camp was Keith Moon, bassist John Entwistle and guitarist/creative director Pete Townshend, all popping uppers, downers and anything in between; in the other, drug-free lead vocalist Roger Daltrey.

The first split occurred in 1965 when Daltrey was fired for punching a spaced-out Keith Moon backstage in Denmark. A year later, after an uneasy reconciliation, the singer left of his own accord. He didn’t know where he fitted in The Who, and wanted to form a soul group instead. But, as before, he was soon drawn back to the dysfunctional family unit.

Townshend’s songwriting was now leading The Who away from conventional white-boy R&B. Their second album, A Quick One, released in winter 1966, included A Quick One While He’s Away, a dark tale of sexual infidelity and Townshend’s first attempt at a rock opera. Later, I’m A Boy, about a lad forced to dress as a lass, and Pictures Of Lily, a hymn to masturbation, returned The Who to the UK singles charts. But Daltrey was unsure whether he could do Townshend’s strange lyrics justice.

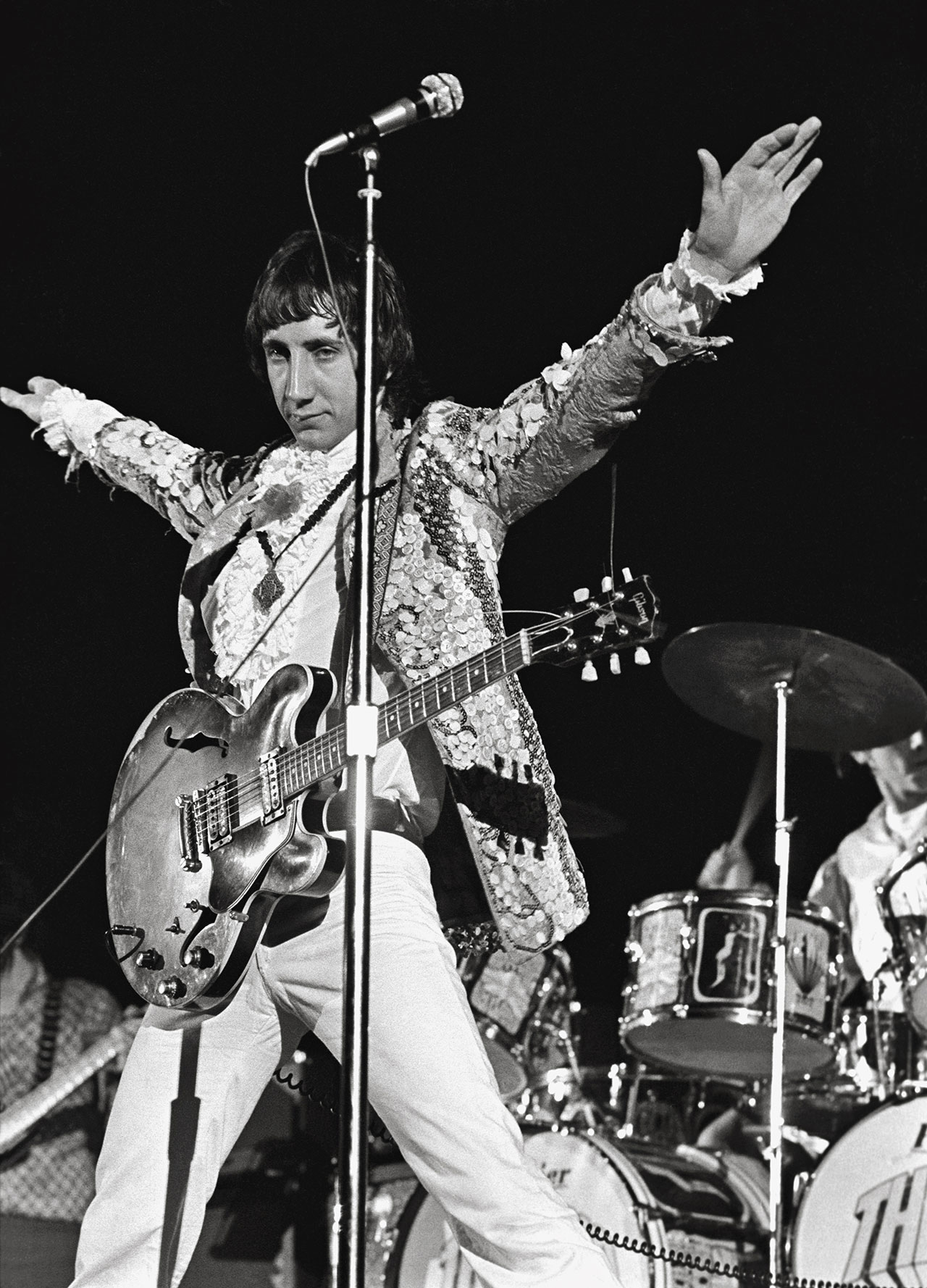

In fact the only thing The Who were sure about was their ability to induce shock and awe in a live audience. They proved that at California’s Monterey Pop Festival in June ’67. Ignoring the fashion for peace, love and flowers, their set climaxed with Townshend and Moon smashing their instruments. The audience were appalled and fascinated.

On paper, then, their latest touring partners, Herman’s Hermits, were the anti-Who. A cheery Mancunian pop group fronted by pretty boy Peter Noone, the Hermits didn’t sing about transvestism and masturbation; they sang old music-hall numbers and songs about beautiful girls. By ’67, America, as well as Britain, had fallen for the simple charms of I’m Henry The Eighth, I Am and Mrs Brown, You’ve Got A Lovely Daughter.

“The acts were totally incompatible, but it didn’t matter,” says Lisberg. “Herman’s Hermits were much bigger, and The Who needed to do some groundwork in America.”

The PR-savvy Townshend immediately created a stir by slagging off the headliners in American teeny magazine 16. “These Herman’s Hermits are the biggest band in America,” he scoffed. “I have a mission to rid the world of this shit.”

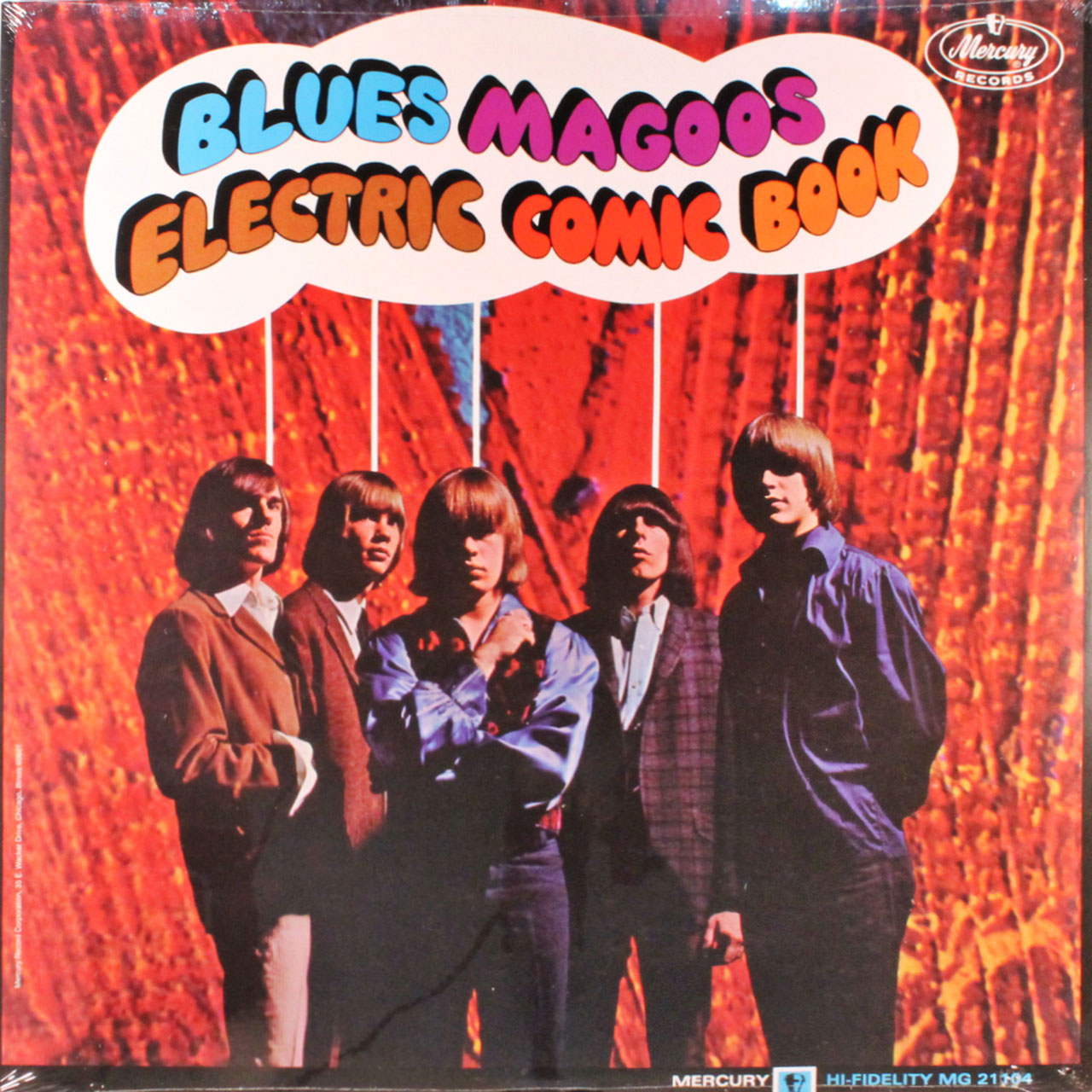

The Who joined Herman’s Hermits and their American special guests, the Blues Magoos, for the first date, in Calgary on July 13. The three groups would spend the next 10 weeks travelling in a chartered DC-9 jet with their names sprayed across its fuselage.

Regardless of Townshend’s criticism, The Who and the Hermits had one thing in common: they were all post-war, ration-book kids, hell-bent on enjoying themselves in a country that until recently they’d seen only in the movies. As Harvey Lisberg puts it: “They were all English, they were all working class and they were all drunk in the middle of nowhere.” What could possibly go wrong?

Five days into the tour came the piranha incident. One source claims Moon left the fish in a bath of warm water before playing that night’s gig at the Vancouver Agrodome. When he returned, the water had gone cold and the piranha was dead. Although Herman’s Hermits drummer Barry Whitwam tells a grislier tale and thinks it happened in Oklahoma City: “Keith put the piranha in the bath and ordered a raw steak from room service. He told the waiter to throw the steak in the bath. And the fish choked to death.”

On stage, The Who’s live show was similarly dangerous, and highlighted the gulf between their music and that of the headline act. The mostly female audience wanted to scream at Peter Noone and hear about Mrs Brown’s lovely daughter. But they couldn’t ignore The Who. Every night, at the climax of My Generation, Townshend smashed his guitar just enough to separate the body from the neck. Later, his roadie glued it back together in time for the next show. “The guitars were crap, but the audience didn’t know that,” Lisberg points out. “It was clever promotion.”

After Vancouver, the tour headed south for dates in Texas, Tennessee and Alabama. “This was our indoctrination into the real America,” said Townshend.

“We all loved black music,” recalls Lisberg, “so it was horrendous to see colour prejudice and black people having to ride at the back of the bus.”

The locals’ prejudice also extended to the visiting Brits with their fancy clothes and hair. In Chattanooga, Moon and the Blues Magoos’ singer narrowly escaped a beating after sauntering into a good old boys’ bar wearing velvet trousers and a sealskin jacket. In several Holiday Inns, the long-haired Limeys were made to wear bathing caps in the swimming pool.

- The Who: Albums Ranked From Worst To Best

- Interview: How The Who salvaged Who's Next from the Lifehouse wreckage

- The Who’s Townshend writes 2 tracks for Tommy touring show

- The Who: How We Made Quadrophenia

Then again, their way of going swimming was rather unorthodox. Moon, Barry Whitwam and Hermits bassist Karl Green had devised a game where’d they’d christen each new motel by jumping into its pool from their respective balconies. “Bloody insane!” says Lisberg. “You’d be sat in your room, and suddenly you’d see one of them go sailing past the window.”

After discovering how painful it was landing feet first in the water, they started wearing shoes. But Moon soon trumped the others. One day, as various Hermits placed wagers on who would jump from the highest balcony, Moon plummeted past from the motel roof, into the pool, dressed in riding boots, a top hat and a cape. All bets were off.

Moon’s 30 minutes on stage every night wasn’t enough to burn off all his excess energy. Bored, homesick and invariably pissed, he desperately needed a distraction – any distraction. In the south he discovered cherry bombs, a firework that looked like the comedy bombs in Tom & Jerry cartoons. They were devastatingly powerful and banned in most states. Naturally, Moon stocked up. “I said: ‘How many of them have you got?’” recalled Townshend. “And he said: ‘Five hundred.’”

Townshend thinks Moon blew up his lavatory in a Holiday Inn in Georgia. Lisberg believes it was Montgomery, Alabama. Moon and Entwistle had already blown a hole in a chair and a suitcase, before tossing a cherry bomb into the toilet just to see what would happen. Moon pulled the chain, but the still-lit firework wouldn’t flush away. The pair ran from the bathroom just as it exploded, sending chunks of porcelain flying.

It was 2am and Lisberg was fast asleep when the motel manager rang him: “Suddenly there was this broad southern accent going: ‘Do you have a mister Moon in your party? The toilet is missing from his room.’” Townshend later inspected the damage. “There was no toilet,” he marvelled. “Just a sort of S-bend coming out the floor.”

As the headline act, Herman’s Hermits were held accountable. The hotel manager gave Lisberg the bill (“I think it was one thousand dollars”), which he passed on to the tour promoter: “We weren’t going to pay. I tried to have a talk with Keith and tell him not to do it again, but he was totally wacko.”

At 27, Lisberg was regarded as the tour’s responsible adult. Peter Noone was 16 when he’d joined Herman’s Hermits four years earlier (Lisberg had to be appointed his legal guardian before their first US tour). But by summer ’67 the Hermits were in their late teens or early twenties, and the mood of sexual liberation emanating from the West Coast had made its way inland.

In every town, the groups would plug that night’s gig on the local radio station. After the concert, whichever DJ they’d met earlier would arrive at their hotel with a troop of young females in tow. “There were millions of groupies,” says Lisberg. “Nobody knew where they came from, but they were always something to do with the DJs.”

Lisberg stationed roadies outside the Hermits’ rooms to keep the younger groupies away. “But they still got in.”

Townshend’s old art-school friend, photographer Tom Wright, joined the tour in Florida. His first 10 minutes with The Who was an eye-opening experience. As the DC-9 taxied down the runway, Wright glanced out of the window and saw a station wagon racing alongside: “We must have been doing about eighty, when the driver produced a double-barrelled shotgun. He pointed it at the plane and fired twice.”

Wright later discovered Keith Moon had spent the night with a young fan, and that the gunman was probably her irate father.

The shots missed the plane. But as the tour progressed, the precarious condition of the old DC-9 became more apparent. After taking off from Providence, Rhode Island, Lisberg saw oil splashing across the window and flames spurting from the engines: “The whole plane freaked out.” It didn’t help that two passengers had just dropped acid.

The jet made an emergency landing in Memphis. Fire crews doused the flames and led the tour party to safety. In response, Townshend composed the Who song Glow Girl: ‘The wing of the airplane has just caught on fire/I say without reservation we ain’t getting no higher…’

Wright recalled Townshend sitting for hours “with his nose in a paperback” in the Memphis airport lounge while most of The Who and the Hermits killed time in the bar. Townshend admitted there were times when he felt isolated on tour. After every gig, Moon and Entwistle would drink themselves into oblivion, while Roger Daltrey entertained the local womenfolk (“The shagging was good” is his memory of the tour). Townshend, however, would retreat to his room alone and dream up ideas for a rock opera he hoped would match The Beatles’ Sgt Pepper.

On their rare days off during the tour, The Who booked studio time in New York, Nashville and Los Angeles to record tracks for their next LP. Among them were the future single Mary Anne With The Shaky Hand (“Another of Pete’s wanking songs,” according to Entwistle), and Rael, an epic piece about global warfare and economic superpowers.

The conflict at the heart of The Who in ’67 was captured in those two songs: the pop single versus the fledgling concept album. And that musical tug of war was reflected in their divergent antics on the road. While Townshend composed rock operas, his bandmates tried to drink, drug or shag themselves to death. That or blow themselves up with fireworks.

The tour reached its pinnacle of excess in Flint, Michigan, on August 23, the day of Keith Moon’s twenty-first birthday. Not that anyone believed it was his twenty-first. Even his close friend John Entwistle presumed Moon turned 20 that year and was lying about his age so he could drink legally in America.

After playing the local high school, the touring party commandeered a suite at the Holiday Inn. Most of the furniture was removed, except for a table on which there were several multi-tiered birthday cakes and two punchbowls: one filled with lemonade, the other whisky and coke.

The groups had been given the use of the suite until midnight. At one minute past, the hotel manager demanded they turn off the music. Tom Wright recalled a drunken Keith Moon grabbing a handful of cake and squashing it in the manager’s face. But no two people can agree on what happened next.

Hermits bassist Karl Green is sure he and Moon got into a food fight, during which Moon tried to rip off his jeans. Green retaliated by tearing off Moon’s trousers and most of his underwear. The local sheriff, appointed to keep an eye on the party, tried to arrest him for indecent exposure. At which point a half-naked Moon, smeared in marzipan and icing sugar, ran away.

This is the point at which Moon’s version of events differed from everybody else’s. Several eyewitnesses, including Townshend, remember him slipping on a piece of cake, falling over and smashing his front tooth. They also remember him being driven to an emergency dentist before spending the rest of the night in a police cell.

However, in a 1972 Rolling Stone interview, Moon claimed to have escaped the cops by running into the parking lot and jumping into the first vehicle he saw: a spanking new Lincoln Continental. He released the handbrake and the car smashed through the surrounding fence and into the hotel swimming pool.

“So there I was, sitting in the driver’s seat, underwater,” he bragged. “Water was coming in through the bloody pedal holes in the floorboard, squirting in through the windows…”

He claimed to have escaped by forcing the driver’s door open and swimming to the surface. The problem with his account is that nobody else saw it happen. Neither Lisberg nor Herman’s Hermits believe the story, and Entwistle, who died in 2002, was equally dubious. Daltrey, however, insists a car did end up in the swimming pool – and that he saw the astronomical bill to prove it.

Herman’s Hermits have always maintained that after Moon was carted off to the dentist it was they who went on the rampage. Various Hermits armed with fire extinguishers sprayed the Holiday Inn’s walls, carpets and several vehicles in the parking lot, stopping only when the corrosive foam stripped the paint from the cars. “Oh God! The foam,” Lisberg sighs. “Everything was covered in that shit.” You wonder, then: did a Lincoln Continental damaged by a Herman’s Hermit somehow ‘become’ a Lincoln Continental driven into a motel swimming pool by Keith Moon?

The Who and Herman’s Hermits were banned from the Holiday Inn chain for life, and the tale of Keith Moon’s twenty-first passed into music biz folklore. But not everybody is a fan. “This day was unpleasant for me,” Townshend wrote in his autobiography Who I Am. “Though it has been turned into an apocryphal joke by everyone involved.”

The Who and Herman’s Hermits said their farewells after a show in Honolulu on September 9. Townshend had failed in his “mission to rid the world of this shit”, and Herman’s Hermits had matched their touring partners for uproarious behaviour. But The Who had one last card to play: their debut US TV appearance on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour a few days later.

Dick and Tommy Smothers were folk musicians-turned-comedians with a nice line in political satire. Tommy Smothers had been a compère at the Monterey festival. But on TV he played the ‘straight’ host and acted bemused by The Who in their Edwardian ruffles and paisley jackets.

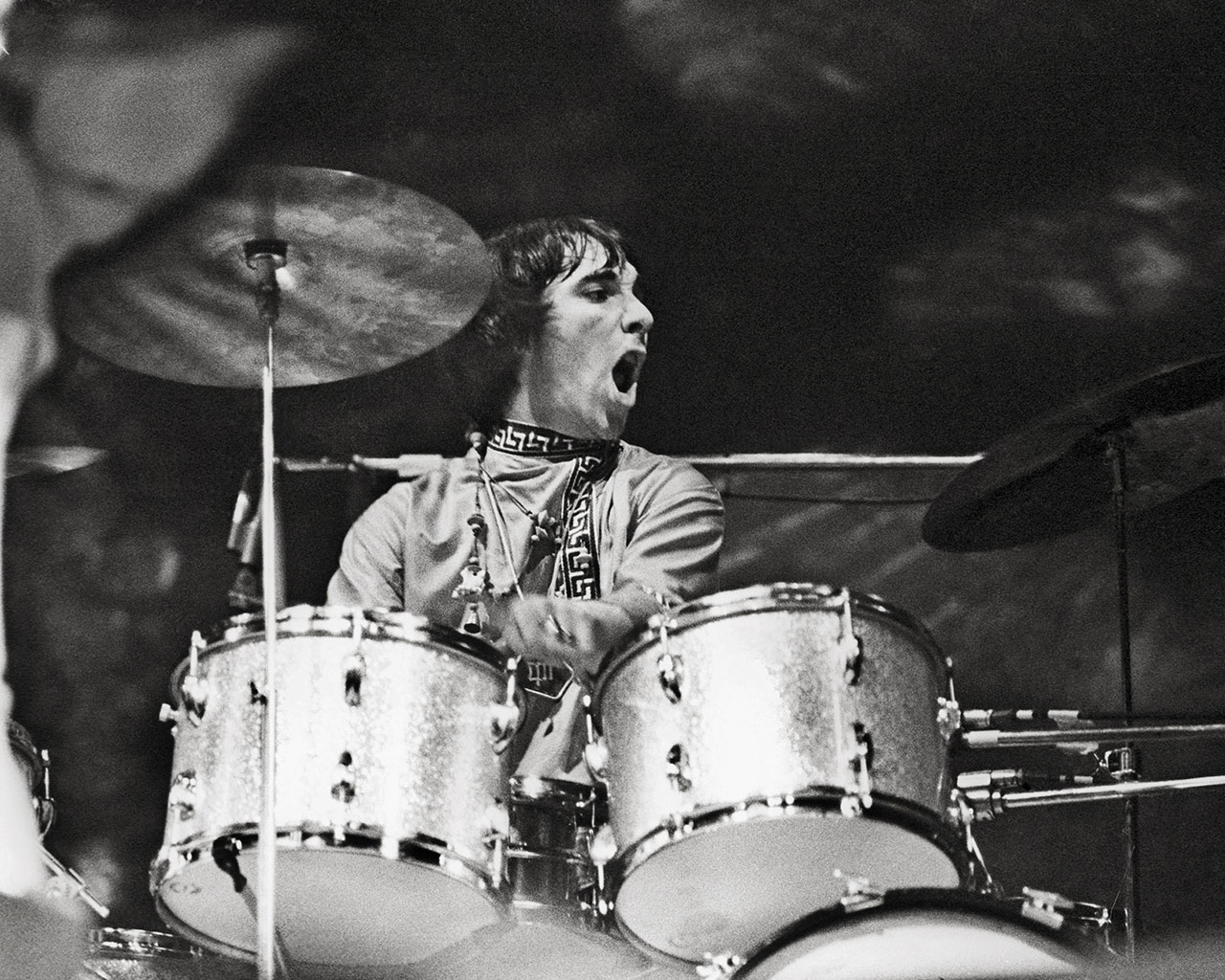

The Who mimed their new single I Can See For Miles, followed by My Generation. At the end, Moon kicked his drums off their podium and Townshend dismembered his guitar. It was business as usual – until a thunderous explosion shook the studio. The TV cameras wobbled as the set filled with plumes of smoke. Through the mist, viewers saw Moon leap from his drum riser and Townshend totter into view with a finger jammed in his ear and his hair standing on end.

The Who knew there was an explosion coming. Moon had a small cannon filled with theatrical flash powder next to his kit. But under Union rules he’d not been allowed to fill it himself. Hearing that was like a red rag to bull, and it’s thought he loaded the cannon with an extra charge when the technician wasn’t looking. Townshend was closest to the blast, and paid the price. “My hair caught fire and my hearing was never the same again.”

The Who returned to England, to find that almost blowing themselves up on TV had given them their biggest American hit yet. I Can See For Miles flopped in the UK, but made the US Top 10. “It was my masterwork,” declared Townshend.

Their next album, The Who Sell Out, a partial concept album inspired by Britain’s pirate radio stations, was witty, satirical and groundbreaking. It was also the first step on the road to Tommy, the 1969 rock opera that transformed the insecure Daltrey into a world-class rock star and The Who into one of the biggest bands on the planet.

After Tommy there would be no more jolly boys’ outings with the likes of Herman’s Hermits. Over time, a dead piranha and an exploding lavatory would seem like relics from an innocent, bygone age. In 1967 The Who went to America intending “to leave a wound”. They achieved their aim. Sadly, Keith Moon, their wayward and talismanic drummer, would wound himself fatally in the years ahead.