While the playful, sassy music videos ZZ Top made for the singles from 1983’s Eliminator wowed MTV and famously rebooted the Texan trio’s career, not every voyager thrived in that brave new world. In 1982, the year after MTV arrived, the video promo was still finding its feet, and Pat Travers, for one, briefly came a cropper.

The promo for the Canadian singer/guitarist’s rather brilliant single I’d Rather See You Dead had a decent enough budget, but its footage of him serenading a deceased fictional lover as she lay pegged-out in her coffin landed bumpily at MTV, even if the corpse did join in at one point.

“I remember it was shot in a mansion in New Jersey”, a laughing Travers says today. “We hired a real coffin, and the funeral-home people were like: ‘You will look after it, won’t you?’ But as soon as they left we were all climbing into it to have our picture taken. I didn’t enjoy making videos, and that one was probably a little too out-there.”

Perhaps remembering the scene in which he and his fellow pall bearers did a little choreographed dance, Travers laughs again and shrugs his shoulders. “What can I say? Videos weren’t my forte, I just did what the marketing people asked.”

Some 43 years on from the Pat Travers Band’s 1980 classic Snortin’ Whiskey (And Drinkin’ Cocaine), Travers is chatting to Classic Rock at his home in Florida. These days he leads a much more temperate existence than that depicted in the aforementioned song, with mindfulness, meditation and practising karate at Black Belt, Third Dan all part of his routine. “I train so I don’t have to fight – that’s how that works”, Travers says of the karate. He still practises guitar every day too. His ongoing activity as a live performer necessitates it.

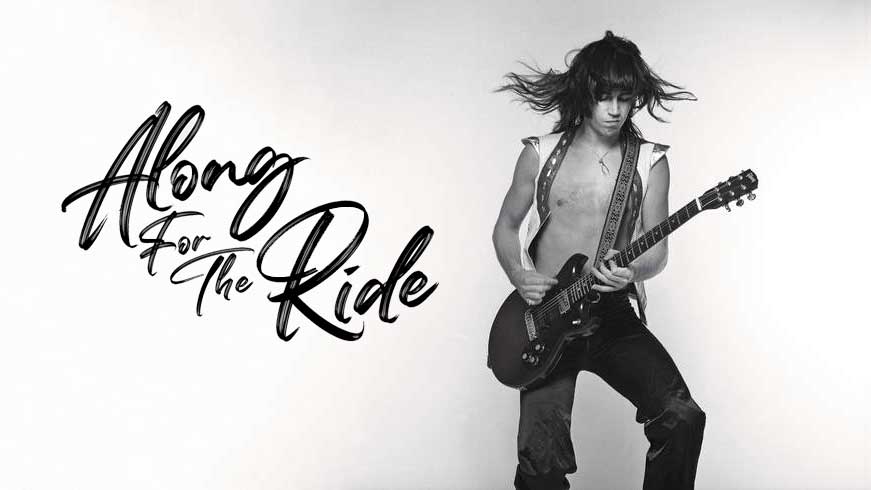

As his ginger cat Archibald pads around the room, Travers chats amiably about past glories, the anxiety that plagued him for years, and the time he almost joined Thin Lizzy. “You know, you think you can manipulate your destiny”, he says, “but most of the time you’re just along for the ride.”

Born in Toronto in 1954, Patrick Henry Travers had a Southern Irish father who was in the RAF, and an English mother who was a nurse. His parents had met in North Africa during WW2, and emigrated to Canada when dad couldn’t find work in the UK. Watching The Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1964 when he was 10 was seismic for Travers; ditto the Jimi Hendrix gig he attended in Ottawa when he was 13.

“At that point Jimi was easily the coolest guy I’d ever seen, and I experienced this beautiful assault on my senses”, he recalls. “I’d never even seen one Marshall stack, but Jimi had three of ’em. It was deafeningly loud.”

In his mid-teens, with his early bands Red Hot then Merge, Travers became a fixture of Quebec’s busy, four-sets-a-night bar scene. Necking Preludin pills to stay awake, he grew worldly wise beyond his years, and at one point backed a transvestite exotic dancer. That was all fine, an education, but the gifted young guitarist was tiring of being “a human jukebox” on the cover-versions circuit. It was Ronnie Hawkins (whose backing-group The Hawks had at one point included all five future members of The Band) who told Travers: “Play to the world, kid, don’t just play to locals.”

Struck by Hawkins’s advice – and mindful of where Jimi Hendrix had first come to the fore – in 1976 the 21-year-old Travers packed his bags and headed for London.

“Was it a culture shock?” he says. “Because of my parentage, not so much as you might imagine. But I do remember feeling a little scared when I landed at Heathrow with just my suitcase and guitar – especially as nobody seemed to know where ‘Downtown London’ was[laughs].”

After finding cheap digs, he quickly found a manager and put together a three-piece band via an ad in Melody Maker. They soon scored a deal with Phonogram Records, but an auspicious-sounding early demo session produced by Def Leppard’s future Midas-touch producer Mutt Lange yielded “nothing useable”.

According to Travers’ recollection, their ill-fated demo session burnt five hours getting a bass drum sound, par for the course given Lange’s famously painstaking approach. The drummer in that short-lived Travers band line-up was Nicky Headon, later ‘Topper’ Headon of The Clash.

In the end another South African, Emil Zoghby, produced Travers’s self-titled debut. Released in 1976, it was heavily reliant on covers, including JJ Cale’s Magnolia and Chuck Berry’s Maybellene.

“Yeah, it took me a while to get comfortable writing”, Travers explains. “At first it felt too much like homework.”

An important arrival was Grimsby-born Peter ‘Mars’ Cowling, the super-tight, alwaysin-the-pocket bassist who would anchor Travers’s music for many albums to come.

“Mars was off-kilter, kinda weird”, Travers recalls of Cowling (who died in 2018). “We got along great. He already had the nickname ‘Mars’ when I met him, but whether that was a reference to him being from another planet I don’t know.”

Liverpudlian Ron Dyke played drums on Travers’s debut, but by 1977’s follow-up Makin’ Magic he’d been replaced by future Iron Maiden drummer Nicko McBrain. When Classic Rock jokes that McBrain’s playing wastighter back then, devoid of ‘big man falling downstairs’ fills, Travers laughs, but says: “Nicko was a naturally funky player, crisp with loads of energy. That was what I loved about him!”

It was Travers’s then-girlfriend Susie, an employee of Phonogram Records, who inspired the album’s Rock ‘N’ Roll Susie, a truly great distillation of gigging and dating, and one of several new originals that marked a huge leap forward in Travers’s songwriting. “Was Susie rock’n’ roll in real life?”, he says. “Absolutely!”

Elsewhere on Makin’ Magic, the layered guitars on Stevie made trailblazing use of echo effects. Featuring former Trapeze/Deep Purple man Glenn Hughes on backing vocals, Stevie was a deeply personal Travers ballad written as a stream-of-consciousness pep talk for his younger brother. ‘Ever since I can remember, you’ve been so talented’, runs parts of the lyric. “And Stevie’s still really talented today”, Travers says. “He still sings and plays guitar in a band up in Vancouver.”

Another Makin’ Magic guest – albeit an uncredited one – was Thin Lizzy’s young firebrand Brian Robertson. Robbo played second lead guitar on Travers’s cover of Blind Willie McTell’s Statesboro Blues, on which the pair incorporate a musical quote from David Rose’s saucy 1958 instrumental The Stripper.

“I’d seen Lizzy play in London in 1976 doing stuff from Jailbreak, and they were just incredible”, Travers says. “I didn’t get to roll with Phil [Lynott] much, unfortunately, but I became real chummy with Scott [Gorham] and Brian. Me and Scott used to play a lot of darts. Treble nineteen was his favourite shot. He’d drink black and tans and throw that dart like a harpoon.”

On Travers’s third album, Putting It Straight, also released in 1977, he hymned his adopted home city on gritty opener Life In London. ‘People are people wherever you go’, he sang. He also documented the new(ish) threat of punk: ‘some kind of revolution’, with its ‘razor blades and safety pins’. Change was afoot, and he sensed it.

Elsewhere on the album, Scott Gorham played second guitar on good-times rocker Speakeasy, which was named after a celebrated nightclub in London’s West End. At the time, the Speakeasy – or ‘the Speak’ as it was sometimes known – was the place for discerning hard rockers out on the lash and/or pull.

“I used to go with Robbo”, Travers recalls. “It was a great place to have [adopts Glaswegian accent] a few bevvies. We would get there pretty late, pretty well-oiled.”

Travers wasn’t at the Speakeasy on the fateful night when Robbo injured his left, fretting hand while preventing his Scots soul-singer pal Frankie Miller from being glassed in a fight. But he does recall the ramifications of that incident – and with good reason: “Lizzy had been due to leave for a US Tour the next day, and with Robbo fucking up his hand they were a man down. There was talk that maybe I could fill in for him. I even had a play with the other guys. But in the end I thought it would be too disruptive for my own career, which was then just getting going.”

The upshot was that Travers stepped down, and regular Lizzy super-sub guitarist Gary Moore stepped in.

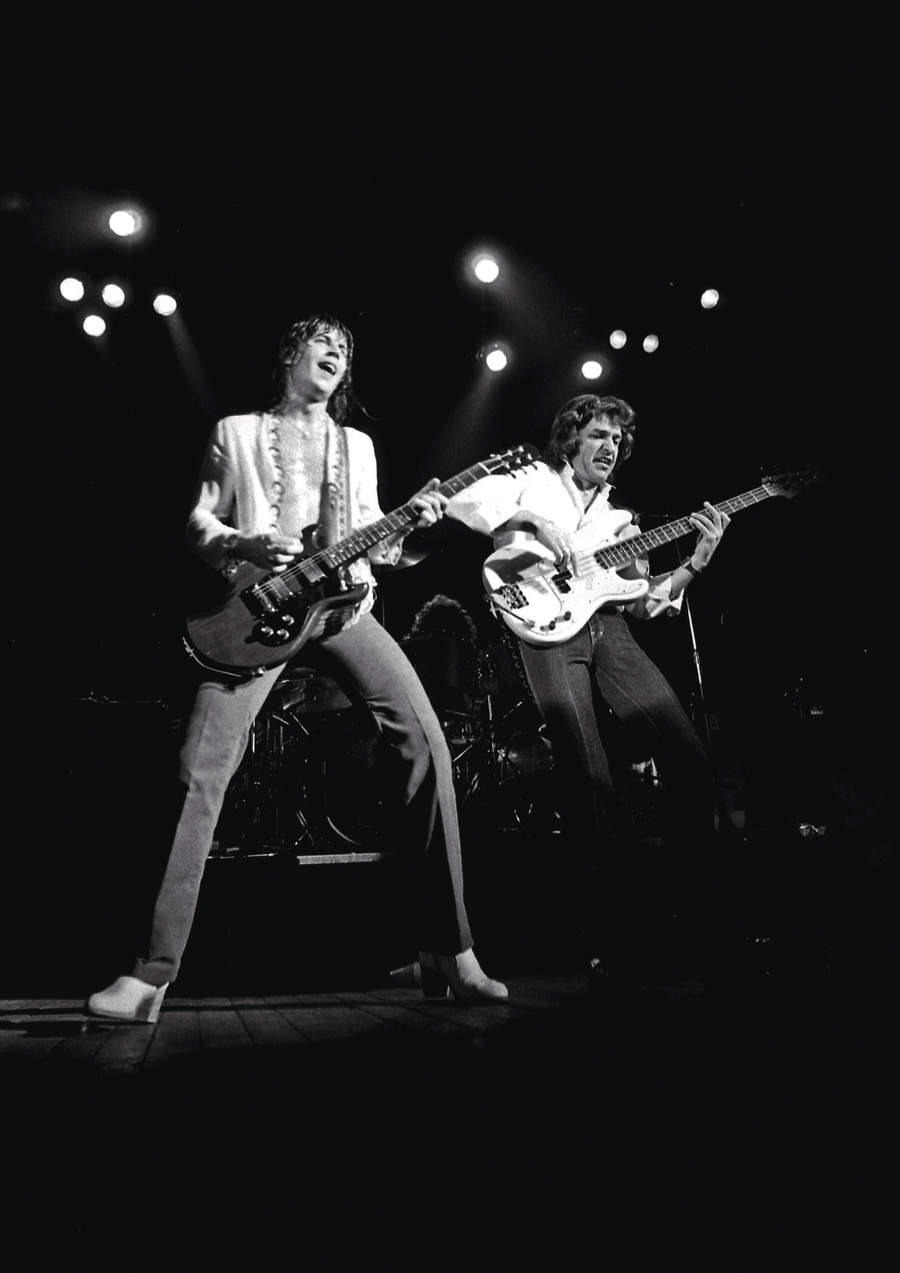

Most Pat Travers Band aficionados agree that the definite line-up arrived around the time of his fourth album, 1978’s Heat In The Street. Having guest guitarists was fun and all that, but now Travers wanted a permanent fixture, a foil. He says it was Journey guitarist Neal Schon who introduced him to Pat Thrall, a tricksy yet highly tasteful young guitar player from San Francisco’s Bay Area. Thrall and Travers didn’t just share their initials, they also shared a certain rock’n’roll appetite too. Further, both had been precociously gifted, rising through the ranks as teenagers.

“I’d always wanted another guitarist in my band”, says Travers. “Pat and I clicked as musicians and as friends. We were both young and skinny and romantically unencumbered back then, so we had a lot of fun. Pat would play this jaw-dropping lead stuff, but he could also be very atmospheric with his sounds. It felt like we had a new engine in the car, and that car was a Lamborghini, you know? We were at the start of great things.”

Heat In The Street also saw former Black Oak Arkansas drummer Tommy Aldridge replace Nicko McBrain. An explosive player given to playing drum solos with his bare hands, Aldridge – together with Thrall and the ever-steadfast Mars Cowling – gave the Pat Travers Band wings. The lasting proof of that is arguably best illustrated by their 1979 album Live! Go For What You Know.

“’Ello music lovers!” announces its cockney-accented compere. “From the streets of Toronto to the streets of London… they’re here to kick your ass!”

And kick our arses the Pat Travers Band most certainly did. From raucous, funky opener Hooked On Music to their infectious party tune cover of Stan Lewis’s Boom Boom (Out Go The Lights), this was a live act that could upstage just about anyone.

“It was a magical time”, recalls Travers. “We’d only been together for about four months, but we were already super-tight. The whole point of the live album had been to buy time to write the record that would become Crash And Burn. But then Boom Boom became a huge radio hit and we had to go back out on the road to promote it.”

Was it a mistake to bring in organ/keyboards for their next album, 1980’s Crash And Burn? Possibly. The record’s title track packed a huge, righteously deep groove, but with Travers behind his Farfisa organ for parts of his band’s first headlining UK tour something was lost and something was gained. Their fine cover of Bob Marley’s Is This Love hit the spot, too. But when Crash And Burn’s debauched rock-riffer Snortin’ Whiskey began gathering airplay, putting Travers on the radar as never before, the album didn’t have the simpatico follow-up that might have brought him true fame.

Asked if Snortin’ Whiskey’s party-animal excesses were an accurate reflection of he and Thrall’s proclivities at the time, Travers, like most re-formed rockers, isn’t overly keen to delineate the (white?) lines of past indulgences.

“We probably started early and finished late”, he says, smiling. “But a lot of bands were much worse than us, I can tell you.”

Still, when he chatted to Thomas S Orwat for the journalist’s YouTube series Rock Interviews, Travers was more candid about the origins of Snortin’ Whiskey.

“Pat Thrall was about four hours late for rehearsal, and he showed up in pretty rough condition”, Travers recalled. “I said: ‘What have you be doing?’ And he goes: [mimes cocaine sniff] ‘Snortin’ whiskey and drinkin’ cocaine!’ I said: ‘That sounds like a song title to me!’ I had the riff already and I wrote the song in about eleven minutes.”

Unfortunately the ‘classic’ Pat Travers Band lineup was short-lived. Legend has it that the wheels came off shortly after their dazzling performance at 1980’s Reading Festival. But on whether that’s true, Travers says: “Not really. There was dissension in the ranks, and around the ranks. Plus I had a lot of problems with my management, and that meant the band got screwed-up too. We’d been due to go to Japan and transition to bigger and better things, but everything just fell apart. It was very sad but out of my control.”

Rising star Pat Thrall quit to hook up with Travers’s old pal Glenn Hughes in Hughes/Thrall. “It wasn’t a surprise”, says Travers. “We all knew each other and moved in the same circles.” Tommy Aldridge left to work with Gary Moore on the Dirty Fingers album, and would soon tour in Ozzy Osbourne’s Blizzard Of Ozz. The ever-loyal Mars Cowling stayed put, but when you got right down to it, Travers was effectively now a solo act. And to complicate matters, his anxiety levels were going through the roof.

When he returned it was with 1981’s Radio Active, a more than decent solo album recorded with New-Yorker Sandy Gennaro on drums. (I Just Want To) Live It My Way and Play It Like You See It were fine Travers originals, but it was his barnstorming, unhinged tale of sleep deprivation I Don’t Want To Be Awake that revealed most. ‘I’ve got demons livin’ inside my head!’ Travers shouts at the end of the track. ‘Gremlins with pick-axes chopping my mind into little tiny pieces!’

“Oh God!” he says now. “That album’s difficult for me to listen to because I was miserable on so many fronts. I was in an unhappy marriage, but it wasn’t her fault. I was anxious about my career, and management were getting weirder and weirder. I also used to imagine and anticipate horrible things happening to my loved ones. It wasn’t until many years later, maybe around 2016,that I was actually able to manage my anxiety through breathing exercises and mindfulness.”

Although touring in support of the Radio Active album had Travers co-headlining North American arenas with Ritchie Blackmore’s Rainbow, the record didn’t do well in the charts and he was dropped by his label Polydor. Travers sued Polydor for breach of contract, and won, which paved the way for 1982’s Black Pearl, which he calls “a really good album, the last of the old-school Pat Travers LPs.”

Intentionally or otherwise, the record’s brilliant stand-out track Can’t Stop The Heartaches seemed to have one eye on drive-time radio, even if it aired a by-now familiar philosophy: ‘You can’t stop the heartaches, the wrong turns your life takes/No, you’re never really in control.’

Black Pearl’s ambition and fuck-it-I’m-going-todo-what-I-want daring came up trumps, with Travers even recording a lead guitar-led version of Beethoven’s Fifth symphony. “I’d always loved classical, and I just thought it would be fun to work it out”, he says of the version he fleshed out with samples of orchestral instruments. Roll Over Beethoven? Oh yes.

In more recent years, Travers, whose admirers include former Rush guitarist Alex Lifeson and Metallica’s Kirk Hammett, has remained prolific – his discography now includes more than 30 studio albums. His 1940s big-band-influenced 2019 album Swing (“Who doesn’t love swing music? It’s so infectious”) was a joyous departure, while last year’s The Art Of Time Travel was a polished, deeply considered album made slowly when the pandemic took Travers – along with everyone else – off the road.

One of that album’s key songs is Ronnie, a heartfelt tribute to friend, fellow guitarist and early influence Ronnie Montrose, whose death in 2012 from a self-inflicted gunshot wound pulled Travers up short.

“I hadn’t known Ronnie had clinical depression, so I was deeply saddened”, he says. “I sat up really late one night listening to [the band Montrose’s song] Rock Candy and wrote most of Ronnie there and then.”

Sad losses aside, today Pat Travers is well. He walks lots every day, and right now is getting ready for his band’s next round of shows. He’s made peace with his past, and those moments all of us have: the ones where we zigged when we should have zagged.

“Having so much anxiety, it was sometimes difficult to enjoy things”, he concludes. “I spent a long time second-guessing myself on everything, but I got over it eventually. Now I can listen back to old stuff and think: ‘You weren’t completely delusional, this is actually quite good!"