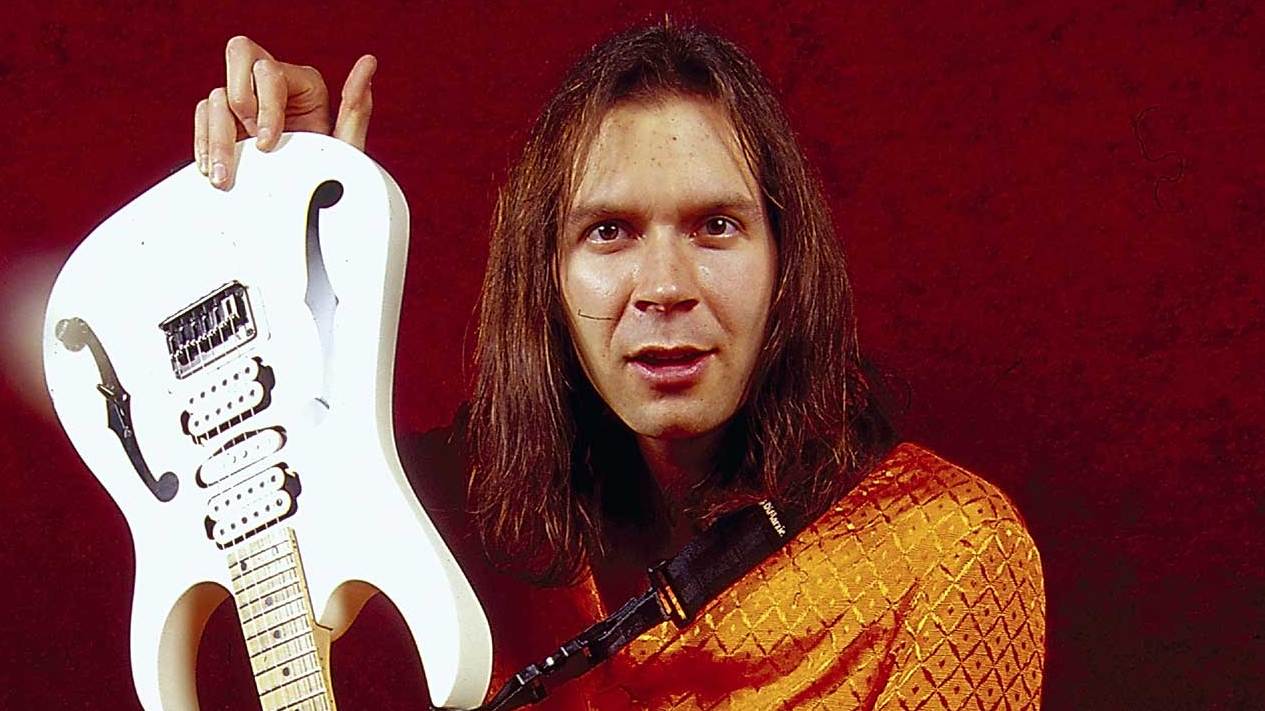

Paul Gilbert’s from budding musical youth in Greensburg, PA, to the glitz of 1980’s Sunset Strip rockdom with Racer X, to worldwide platinum sales with Mr. Big, to unwavering respect from musicians of every genre, has been paved with stylistic shape-shifting, billions of perfectly picked notes, and probably more broken guitar strings than he’d care to admit.

For Paul, who in 2016 celebrates 30 years of recorded music, he wouldn’t have it any other way. Making his recording debut back in 1986 with the Los Angeles-based Racer X, he probably never fathomed the incredible evolution he’d make not only as a musician but as influential instructor. Now synonymous with everything from Ibanez guitars to DiMarzio pickups, he’s spun a full 360 degrees over three decades – known as much now for the notion of his self-coined “terrifying guitar” as scoring a #1 pop single with Mr. Big’s To Be With You.

Gilbert’s name was the stuff of legend even before Racer X’s Street Lethal debut – a record featuring a group of fresh-faced fellow GIT students (Guitar Institute of Technology, now Musician’s Institute) with Racer X’s drummer Scott Travis going on to Judas Priest fame. Hired as a guitar instructor at the heralded GIT even before he turned 21, Gilbert notoriously asked Shrapnel Records head Mike Varney for an audition in Ozzy Osbourne’s band – Gilbert was all of 15 years old at the time? Varney may not have secured a gig with Osbourne, but he did offer Gilbert a record deal a few years later.

“I did send some tapes to Mike – he really liked my playing, even if he said my songwriting needed some work,” remembers Gilbert with trademark jocularity.

The story of Paul Gilbert the shred-guitar demon is well-documented, but not much has been said about the method behind his madness, or the crafty songsmith that lies beneath – he’s released some 14 solo studio records since 1998, all of which contain a mesmerising meld of melodic inflection and guitar space-oddities. Paul’s got much to offer on the topic, as do some friends happily caught up in his wake.

“GIT classes were packed solid in the mid-1980s,” recalls Keith Wyatt, guitarist for roots/Americana act, The Blasters. Wyatt was an instructor at GIT during the time Gilbert arrived at the school, and the two have remained close to this day. Wyatt says that Gilbert stood out from the hundreds of other aspiring guitar heroes for a few good reasons.

“He had skills and musicality far beyond his years,” begins Wyatt, “he was passionate about learning, and he had a wild imagination and sense of humour about the whole thing.” Wyatt lists examples as describing shred guitar in terms of “playing cards on bicycle spokes,” which would later materialise as a power drill attached to a pick (check out Mr. Big’s Daddy, Brother, Lover, Little Boy). Even though Racer X were packing clubs on the weekends, he’d always head back to the woodshed after the parties ended.

“Paul still showed up for class on Monday, and soaked it up like a sponge,” Wyatt notes. “His enthusiasm for knowledge and education never stopped. He’s as devoted to his students as he is to performing.”

Gilbert’s fretboard antics have crossed generations, as evidenced in younger players like Nita Strauss, currently guitarist for the Alice Cooper band. Strauss, an admitted Gilbert devotee, recalls the first time she heard the inspirational licks emanating from her speakers.

“I was 13, and just starting to play guitar,” she recalls. “I saw a VHS tape of another guitar player shredding on this insane song. I immediately showed it to my older bandmate, who matter-of-factly said, ‘Oh, that’s Scarified (from Racer X’s Second Heat). I was totally blown away watching it; not only by the technical proficiency of the song, but how much fun it sounded to play!”

Strauss notes that in the often frustrating world of “shred” guitar, Gilbert and Racer X heralded a more celebratory tone within the music.

“It was the joy of shredding, not taking themselves too seriously,” she explains. “Now, years later, Alice’s (Cooper) drummer Glen Sobel and I play Racer X songs at soundcheck from time to time. By the end of it, we’re both smiling and laughing. Because Racer X songs are challenging, they’re ‘technically difficult.’ Most of all, they’re a blast to listen to and to play – that’s what I like most about them.”

Gilbert himself has an interesting take on his shred ‘guitar god’ status.

“It was a little strange to be labeled something that didn’t exist,” he says, due to the fact that the term ‘shred’ had yet to be officially coined in the mid-80s. “When I was a kid, I wanted to be a ‘heavy metal’ guitar player – that term resonated with me. If I step back from it, I’m really fortunate that people are calling me anything. To be a musician that people will pay attention to is really an honor and a very valuable thing to me. As long as people are listening to it, they can call it whatever they like.”

The Racer X albums Second Heat in 1987 and Live: Extreme Volume in 1988 would further cement Gilbert’s status as a guitar wizard. Gilbert’s initial run with Racer X held to 1989, when he would form Mr. Big. His teaming with bassist Billy Sheehan was the stuff of music store chatter in 1989, although it was becoming clear that the songs were Gilbert’s focus.

“The first Mr. Big album was a transition for me,” Gilbert reflects. “What I did, was kind of step back and listen, watch, and learn from the other guys in the band. I certainly contributed to the record – a lot of the songs were based on riffs I wrote, but some of the ideas were really foreign to me. Maybe what it was, was that I grew up with The Beatles, but I didn’t really grow up with soul music. Eric (Martin, Mr. Big vocalist) was really into that sort of thing. I love that music now, but a lot of stuff that Eric was doing – I never would have thought of it myself. Whenever anyone would have an idea like that, my gut reaction was like, ‘I don’t know about that.’ But, I held myself back and would always listen and give it a chance.”

Gilbert came into his own with Mr. Big on the band’s second album, Lean Into It in 1991 – the album featuring the monster acoustic ballad To Be With You. On this album, Gilbert would begin to write “complete” songs, like Green-Tinted Sixties Mind and A Little Too Loose. It was the touring behind the first Mr. Big album with Rush that led to a major revelation for him.

“I was a huge Rush fan, and it was great to play with my heroes, but we also had the opportunity to play these big venues in front of a lot of people,” he begins. “I thought we were playing really well, but the songs just weren’t connecting with the audience. I thought we needed songs that would really connect. When we set out to write Lean Into It, that was my goal – to write songs where the melody would stick. So, that’s where we got To Be With You, Just Take My Heart, Green-Tinted Sixties Mind, and all of those. The next tour was a whole different reaction from the audience, and our success went through the roof.”

Some of Gilbert’s post-Mr. Big solo albums, like 1998’s King Of Clubs, would continue to showcase his more ‘song-oriented’ work. The record is filled with quirky, sugary power-pop tunes like Girlfriend’s Birthday and Vinyl – some of the most impressive radio-friendly work he’s done outside Mr. Big.

“There were just some things I had to try,” Gilbert says about leaving Mr. Big during the mid-1990’s. “We had so much success, especially in Japan, but I felt that it wasn’t me that was succeeding. I wanted to put the real me out there and see what the reaction was; for myself as well. I wanted to make the music that I would listen to. I was getting heavily back into pop music at the time, back into The Beatles and Cheap Trick. This was probably a strange move to people that were fans of my playing, but I was really fortunate to try that and see where it went.”

John 5, guitarist for Rob Zombie, wears his admitted Gilbert influence on his sleeve. One listen to John’s recent solo cuts like Black Grass Plague have Gilbert’s psychopathically arpeggiated, fleet-fingered stamp all over them. John 5’s comments provide perhaps the most cohesive take on Paul Gilbert’s legacy.

“Paul wasn’t an imitator, he was an innovator,” John says. “He would come up with these things like string-skipping; he was shredding and it was definitely his own style, influenced by Yngwie and all these other players. We always talk about his guitar playing, but he’s also a really great songwriter. You can’t just have great guitar playing; you need songs to back it up. Paul’s an incredible musician and definitely one of my favourite guitar players. He’s also a great teacher; he’s helped millions of players with his instructional videos – that’s really imperative.”

Gilbert admittedly never sought the position of teacher growing up. He says he was more interested in “buying orange pants and pointy guitars to play the rock star.”

“The things that have changed for me are, being able to actually listen to my students,” he admits. “It’s one thing to stand in front of a class with a seminar, but you have no idea if it helped, because you’re not hearing people play. In my online school in recent years, I get to hear everybody play – anyone who sends in a video, I listen to them. To prepare for all this, I went back to Musician’s Institute, and I did over 100 private guitar lessons with 100 different people, just to get to listen to them and get a sense what the people need, what they’re struggling with. That led me to do a very different guitar course for my online school – the communication is enormously helpful.”

Thirty years on, Paul Gilbert answers the question of legacy with a humble, simple response.

“I’d just love to leave something that stands up to my own criticism; to my own ear. A lot of it does – when I listen back I think, ‘Oh yeah, that worked!’ Not everything worked, but a lot of it did. I’m very happy with that.”