In retrospect, it’s easy to pull at the threads of The Beatles’ studiously scrutinised timeline and examine the source of their unravelling; to point fingers at the capricious actions of each member who may have abdicated (albeit temporarily) along the way, and to speculate on the heroes and villains of their illustrious story.

But to the outside world at the time, which was largely unaware of the degree to which contempt had risen within the group, the ending of The Beatles was defined on April 9, 1970, when Paul McCartney announced – via a press release intended to promote his debut solo album, McCartney – that he had no intention of continuing to work with the group.

“Personal differences, business differences, musical differences” were his reasons for the break, he wrote, “but most of all because I have a better time with my family.”

Of course, we know now that McCartney’s declaration was merely the first public confirmation of the Fab Four’s dissolution – an increasingly distracted and dissatisfied John Lennon had requested a “divorce” during a private band meeting the previous September – but still, the other Beatles were incensed.

Despite the tangible tensions and fragmentations in the group, which undoubtedly rose to the surface after the death of manager Brian Epstein in 1967, heightened amid the strained recording sessions for The Beatles (aka the White Album), and came to a head with the aggressive legal wrangles that sought to salvage their Apple Corps business, it was presumed that The Beatles could endure as a recording unit, and coexist with individual solo pursuits.

“We’re not breaking up the band,” Lennon had told a journalist in January 1970, “but we’re breaking its image.”

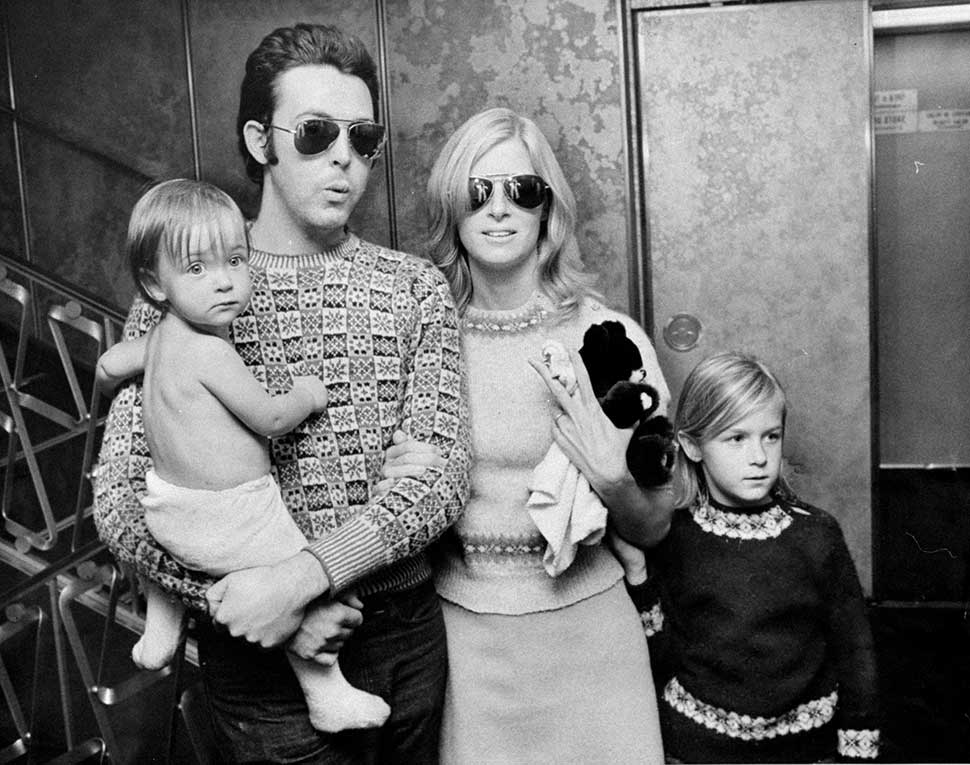

It was the unwavering love and support of Linda that coaxed her husband out of his state of despair. With her encouragement, he would begin to emerge from the grief and sorrow that had engulfed him with the intent to channel his restless energy into a batch of new, unrestrained and cathartic songs.

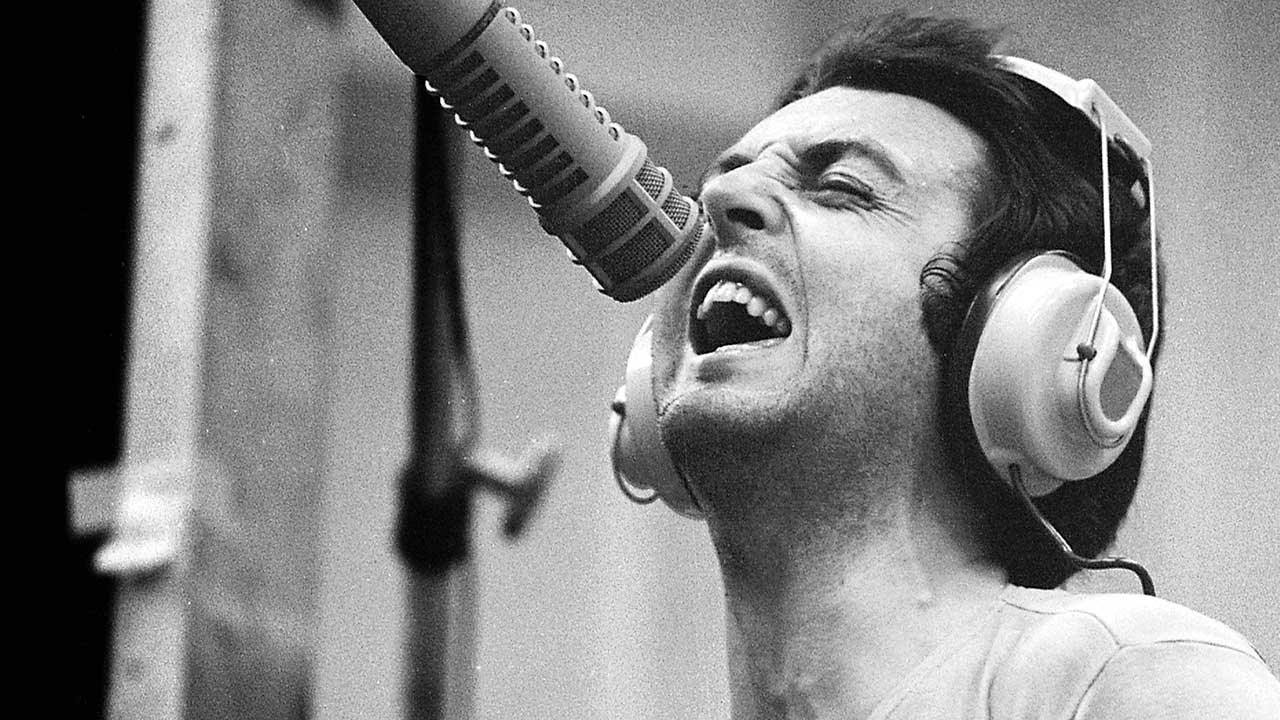

Having returned to London in late December 1969, he started work on McCartney in his St. John’s Wood home, where a four-track tape machine recorded intuitive and experimental sessions that delivered the album’s rudimentary tracks. Although he would later embellish these elsewhere – including at Abbey Road Studios, a stone’s throw from his house – the songs, with all the instrumentation played by McCartney, retained a distinctly homemade quality, with simplicity, improvisation and contentment at the heart of its primitive charm.

Impromptu instrumentals such as Valentine Day and Hot As Sun/Glasses sat coolly alongside meditative White Album leftovers Junk and Teddy Boy, extolling a sense of impulsive invigoration, while the levels of devotion and gratitude that Paul felt for his wife were evident in lilting acoustic opener The Lovely Linda and the rousing resplendence of Maybe I’m Amazed.

“I loved that record because it was so simple,” Neil Young would enthuse in 1999, as he inducted McCartney into the Rock And Roll Hall of Fame. “It was just Paul. There was no adornment at all… There was no attempt made to compete with the things he had already done. And so out he stepped from the shadow of The Beatles.”

However, in pushing ahead with the release of McCartney Paul became further ostracised from his estranged former bandmates, intensifying the conflicts that had separated him from the other three.

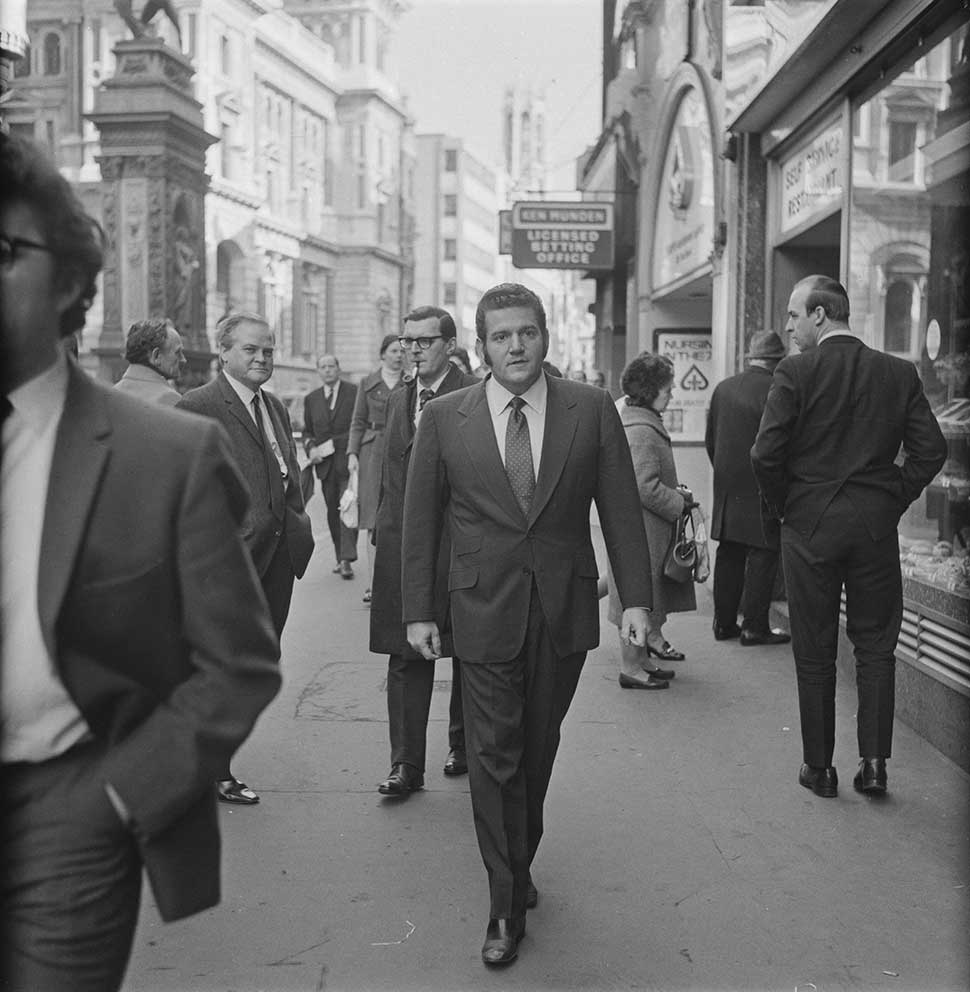

There had always been simmering resentments since McCartney assumed the lion’s share of responsibility to galvanise The Beatles and navigate their affairs after the death of manager Brian Epstein. And it must be noted that as individuals, each growing up, falling in love and maturing as artists, they were naturally gradually drifting apart, but the immovable wedge that irrevocably divided them was the installation of Allen Klein as the band’s business manager.

An uncompromising and aggressive businessman of nefarious repute, Klein was nominated by John Lennon, George Harrison and Ringo Starr to oversee operations, based on the managerial successes and financial recuperations he’d finagled for Sam Cooke, The Animals, The Kinks and, most recently, the Rolling Stones.

McCartney was firmly opposed to Klein’s gruff bullying tactics, and put forward his father-in-law, American attorney John Eastman, as an alternative, but he was outvoted, and eventually Klein won control of The Beatles’ empire.

Now, with McCartney ready for release, they were all attempting to stand in Paul’s way. Ringo’s solo debut, Sentimental Journey, was scheduled for an April 1970 release, and such competition was deemed unfair. Moreover, The Beatles’ Let It Be album would be forthcoming, which should be given promotional and marketing priority.

The latter was especially galling for McCartney, who had been enraged by the enlistment in early 1970 of famed producer Phil Spector and his entrustment – at the behest of Klein – to piece together and polish the assorted picks from lengthy Beatles sessions the previous year and turn them into an album. Then, by overdubbing orchestration and other elaborations on McCartney’s song The Long And Winding Road, without consultation or permission, Spector incurred the wrath of an artist whose prized creation had been unceremoniously vandalised.

“In future no one will be allowed to add or subtract from a recording of one of my songs without my permission,” McCartney wrote in a scathing letter to Klein. “Don’t ever do it again."

Exasperated by his predicament and treatment, he looked for a way out. Attempts to reconcile throughout the summer of 1970 proved futile, and on the last day of that year McCartney launched proceedings to extricate himself from The Beatles’ contractual partnership the only way he could: by suing his former bandmates.

1971, therefore, was going to be another tumultuous year. But McCartney already had a welcome distraction from the nastiness, in the shape of his loving young family, plans for a new album, and a much-needed change of scene. His heart was elsewhere: in the countryside.

We were living in Scotland on the farm under very basic circumstances,” he recalls, looking back to that summer when the family again decamped north. “I mean, I said I wanted to get back to basics, but I think we got back beyond basics! We were like squatters in our own house! It was pretty damn funky.”

In stark contrast to their city habits, the agrarian lifestyle seemed to suit the couple, and Paul threw himself into the farm’s routines, with mowing fields and shearing sheep among his duties. Immersed in the slow yet busy pace of austere domesticity – Linda was pregnant with Stella at the time – the move afforded Paul a fresh perspective from which to approach his next chapter.

“I’d had a little chance to kinda settle into my new circumstances with Linda, and now it was kind of a little bit easier to look at future plans, because my personal circumstances were a little more comfortable,” he explains. “So I was able to take some time and start planning the kind of album I wanted next. And having done a homemade ‘front parlour’ album [McCartney], I now wanted to kind of expand a little bit. I was ready to open my horizons.”

He’d amassed a set of songs that were as bucolic as the surroundings in which they were created. Some were written in their “wee garden” with “the kids running around… and the sun would be shining”, while others came to fruition on a family holiday to France. The lyrics attested to a sense of fulfilment, were imbued with a radiant cheerfulness, and glorified the idyllic intimacy he relished with his family. In the allusively titled Heart Of The Country, for example, one evocative verse enthused: ‘Want a horse, I want a sheep/I want to get a good night’s sleep, livin’ in a home in the heart of the country.'

To bring them to life, however, Paul decided that this time around a collective effort would paint the most vivid picture. And so his thoughts turned first to who might make the perfect partner – the foil with which to spur his creative process. The ideal candidate, he realised immediately, was sitting right beside him.

“I remember one night saying to Linda: ‘I’m gonna form a band. Would you like to be in it?’” he says. “It was just a natural, organic thing to have happen. And with some trepidation, she kinda said: ‘Er, yeah.’”

Aware of Linda’s then limited musical talents, and the accusations of nepotism he would face, McCartney nevertheless brought his wife into his band in an instinctive gesture that verified the level of appreciation he felt towards the woman who had nurtured and protected him at his lowest ebb, and was characteristic of their inseparable marriage.

“That was one of the amazing things about our relationship actually,” he reflects, “a fact that never really seemed to me – or her, I think – to be unusual. We just happened to be together. It was like we just hung out together a lot. And as our family grew, there was even more reason to hang out.”

But more hands would be required to assist with making the new album. And while one would assume the pressure to maintain the degree of pre-eminence that The Beatles enjoyed would weigh heavy on him, McCartney opted to uphold the back-to-basics policy he had initiated. A supergroup was the opposite of what he wanted. He was going to start this new group from scratch.

Linda made arrangements to hold auditions for musicians in New York, and so in October the McCartneys flew to the States to put together their band. Over three days in Midtown Manhattan they tried out a succession of guitarists and drummers that had been recommended through their network. David Spinozza, a young R&B session guitarist, made the cut.

“I remember there was a drum set, keyboard, amps and some guitars in the room,” Spinozza recounts. “Paul asked me to play some chords in a straight eighth-note feel [G to B7 to E minor]… He had also wanted to know if I played keyboard and drums, which I did, a little. He asked me to play both, so I did… I guess he knew what he was looking for.”

The drummer who impressed the most was Denny Seiwell. “I think I came in with a good attitude,” he reasons. “I said: ‘Well, what do you want to hear?’ and he said: ‘Just play some rock’n’roll time’. So immediately I thought: ‘What would Ringo do?’ So I went to the tom-toms and just kicked ass for thirty seconds or whatever. He said: ‘Well, how about a shuffle?’ He had me just go through a few different flavours and styles of rock’n’roll drumming, and I did so gladly.”

“We kind of hit it off right away,” Seiwell adds. “I made him laugh a few times, we had a few giggles. It was a really fun thing. I don’t think I was there more than fifteen or twenty minutes, and then he said: ‘Fine, we’ll let you know.’ And then I left.”

After the personnel choices were confirmed, the team soon convened at CBS Studios on 52nd Street to begin recording basic tracks. Each song was presented to the group as an almost complete arrangement, and they would be expected to fill in the gaps.

“I would say: ‘These are the chords. I’d like you to do this riff here, and this is the speed of the song, and this is how the words go,’” McCartney comments. “I wouldn’t say: ‘This is exactly what you have to play.’ So then within that framework people would then come up with their own ideas, and then once that was sounding okay you’d go and do a take.”

“Every time you heard one of these songs, you’d go: ‘Oh my god, this is really special,’” Seiwell says. “I thought it was better than most of the stuff that I was used to hearing from the Beatle period. This was really interesting music.”

“We worked on a song per day,” guitarist David Spinozza explains. “We’d get in at nine a.m. and go to five p.m. It was very efficient. I was used to sessions with music charts written out, and an expectation in getting at least three songs recorded in a three-hour session. So it was a different style of working for me. Paul wanted us to learn the songs like a band and work on the parts until they really gelled.

"I enjoyed listening to the songs come to life, and it was a luxury to do one a day and not have the pressure of getting three done. I also thought the tracks came out really special that way. He has a knack of making every track a special sonic experience."

Over the next four weeks, the foundations were laid for the songs that would eventually make up the album, given the title Ram. During this process Spinozza – who had lined up another job to start after his contracted time with McCartney – was replaced by renowned guitarist Hugh McCracken, fresh from sessions with soul star Aretha Franklin.

After breaking up for the Christmas holidays, they returned to New York to resume work in January. This time they also holed up at A&R Studios on 7th Street, working with A&R’s founding producer Phil Ramone and Dixon Van Winkle. Here the group completed the backing tracks and added overdubs and lead vocals.

“When I first heard the rhythm tracks, I just thought: ‘Wow!’” says Van Winkle, who was sent the CBS studio sessions tapes prior to McCartney’s arrival at A&R. “I mean, the songs themselves were so great, and Paul got these great musicians in. It was a wonderful rhythm section – you couldn’t beat that.”

Also recorded at A&R were the orchestral arrangements for the songs, four of which (Dear Boy, Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey, Long Haired Lady and Back Seat Of My Car) were scored by The Beatles’ longtime producer, George Martin, in his first collaboration with McCartney since Abbey Road in 1969.

“With Ram, as always, we worked closely and well with each other,” Martin disclosed in 2011. “It was a shame the recordings happened in New York – I missed out on those. But it seemed the scores worked out okay without me. Mostly the scores were straightforward. They are always templates which can be modified on the session. Quite often I would make on-the-spot changes to make the arrangements work better. And Paul had such a vivid imagination he could easily have done the scoring himself if he had a little instruction.’”

Finally, the tapes were taken to Sound Recording Studios in Los Angeles where, after some last-minute extra overdubs, they were mixed by engineer/producer Eirik Wangberg, who was also charged with choosing their sequence on record.

“I became at least in a state of shock, how he trusted me,” Wangberg says. “A few hard days and evenings followed choosing tracks, sequencing, cutting and splicing them together. Then I called and said: ‘Now you can come and listen to Ram.’ Paul and Linda sat down, listened intensely, and commented with joy as they heard the album for the first time.”

What they heard was the sound of freedom: a series of signposts mapping the route from desolation to salvation. Alongside the aforementioned Heart Of The Country, which bounces like spring lambs, Eat At Home, a more dynamic rocker stuffed with suggestive innuendos, is another paean to the pastoral pleasure the McCartneys derived from their private hideaway. Long Haired Lady, a coruscating composite of three individual song sketches, is a love letter to Linda in which Paul’s reverence to her is all too palpable.

“Right after I had finished a mix to Long Haired Lady I turned around to see his reaction,” Van Winkle recalls. “I knew the mix was final; tears were running down his cheeks.”

Paul explored the couple’s profound connection further in Dear Boy, an imagined communiqué to Linda’s ex-husband – “a very nice guy called Mel,” Paul points out. “I kinda felt like he had missed Linda – he’d not seen in her what I had seen in her – and so the song was really written to him. You know: ‘You’ll never know what you missed, dear boy.’”

The luscious, layered vocal harmonies in Dear Boy were inspired by the Californian sunshine in which they were recorded (plus, of course, the Beach Boys, Paul’s eternal source of harmonic inspiration), and were Linda’s first real studio vocal performance, done with the reassurance and support of her studio-veteran husband.

“What I liked about Linda’s singing was the tone of her voice,” Paul says. “I’d never worked singing with a woman before, all my harmonies to that date had been with males, so I liked this idea of her range. But she wasn’t a professional singer by any means.”

“I put my part on,” he continues, “and then encouraged Linda to just take it easy, relax, put a good performance in, which she did. Years later some of my really cool, professional friends who knew what was good and what wasn’t would listen to those harmonies and point them out and say those are really great harmonies. I remember Elton John commenting on that, and I remember Michael Jackson commenting on that.”

The multifaceted complexities of Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey and The Back Seat Of My Car, which bring to mind The Beatles’ innovative studio adventuring, especially the shifting Abbey Road B-side medley, nonetheless retain a wholesome organic flavour, and stand out as Ram’s more potent moments.

Perhaps the most consequential of all the tracks, however, was Too Many People. The assertive album opener, it reflected the still raw relations between McCartney and Lennon, and made a retaliatory strike against his once closest compadre, who’d been especially critical of Paul in the press, taking lyrical potshots at John’s political posturing. ‘Too many people preaching practices,’ he railed, ‘don’t let ’em tell you what you wanna be.’

“And it was directly aimed at John,” Paul confirms, “but it was about our relationship at that time, and me feeling that I didn’t need to be preached at.”

Understandably, it ignited a war of words played out through song that would last a couple of years, with Lennon’s ire, McCartney suggests, being deliberately stoked by Allen Klein. On his 1971 album Imagine, Lennon replied with the caustic cut How Do You Sleep? ‘The sound you make is muzak to my ears,’ he snarled. ‘You must have learnt something in all those years.’

“I had two options,” McCartney says of the ongoing slanging match. “Either to not reply, not respond, or, if anything occurred to me, to just put it down as a song… I soon got fed up with that idea. It occurred to me once to send a grenade back at him, but it wasn’t really something that I enjoyed doing.”

As The Beatles’ courtroom dramas persisted through the early 70s, this bitter narrative kept the pair publicly at loggerheads until, McCartney insists, they “got it out of our systems” – ostensibly following the removal of Allen Klein in 1973, after a disgruntled Lennon, Harrison and Starr uncovered his malpractices and initiated their own litigations against him. “So it kinda settled down,” he continues, “and then eventually the Beatles mess got sorted out, and then we were able to talk to each other like human beings and friends.”

By the middle of the 70s, relations between McCartney and Lennon had warmed considerably, their visits together in the States offering a glimpse of hope at the prospect of a future Beatles reunion. Their last meeting in person was in New York in 1976, four years before Lennon was murdered. “That was something I was really always very glad of – the fact that we got back together again as friends,” McCartney says. “Because we’d been through too much to let business arguments blow up our whole relationship. So when we got it back it was a good thing.”

Ram was released on May 17 in the US and on the 28th in the UK. Its cover photo of Paul grappling with a ram was shot by Linda during shearing season on the farm. As well as providing an authentic portrait of the rustic style of living that so infused the music, it also illustrated plainly one of the title’s double meanings.

“It’s strong, it’s a male animal,” McCartney says. “And then there’s the idea of ramming – pushing forward strongly – which I thought was pretty cool.”

It was also decidedly significant in that the whole album – its genesis, its subject matter, its creation, its release – was an exercise in pushing on. McCartney had to forcibly impel himself forwards so as to be liberated from under the weight of all the acrimony, dread and vilification that dampened his creativity as The Beatles fell apart. But the fight wasn’t quite over yet.

“Ram represents the nadir in the decomposition of sixties rock thus far,” critic Jon Landau would write in Rolling Stone. Calling it “monumentally irrelevant” and “emotionally vacuous”. His stinging review even suggested that “Paul is not happy in his role as a solo artist, no matter how much he protests to the contrary”.

But his assessment of the album could not have been more mistaken. Certainly the record-buying public were quick to disagree. Ram topped the charts in the UK and US, while its lead single, Another Day, a song first tried out during the Let It Be sessions, reached the top five in both countries.

These successes validated the strenuous efforts McCartney went through to create this album, paid off the perseverance he showed in defiance of crippling mental anguish, and substantiated conclusively the momentous magnitude of a new creative partnership with his wife. Accordingly credited to both Paul and Linda McCartney – the only album ever to do so – Ram was the spark that reignited Paul’s passion for making music.

In fact he treasured the songs so much, he commissioned the entire album to be translated into an orchestral version. Titled Thrillington, it was arranged by producer Richard Hewson and recorded a month after the completion of Ram – without any appearances from McCartney – but wasn’t released until April 1977, credited to a mysterious ‘Percy Thrillington’ (“I was hoping to remain anonymous,” McCartney says with a laugh. “I basically enjoy lying!”), the album duly sinking into obscurity.

Today, for all Ram’s associations with redemption, McCartney regards it as his favourite solo album. “It was some of the best stuff that he did – definitely since leaving The Beatles,” offers drummer Denny Seiwell.

At the time, the purpose of Ram was just to do something. To write, to create, to prove to himself that he could do it, and that a new direction was required if he was to avoid lazy comparisons to The Beatles and to invigorate his livelihood as an artist. In that process of self-discovery, he says, some of the components of creation were “quite throwaway”. But looking back 50 years later, it’s exactly that unconventional makeshift quality that endears it to him so much.

“Whatever went down,” he says of the turbulent events of 1971, “I got caught up in it, so I assumed that a lot of stuff I did then was no good. But now when I go back to it I sort of think: ‘I remember why I did that. There was a reason for it; it wasn’t just some flippant off-my-head gesture.’

"So looking at it now, like a lot of things in retrospect, it looks better than it looked to me then."