“I wanted to keep riding it – let's do it and see how far we can ride this. I was also caught in the whirlwind of the excitement of it. Counter to that Ed wanted to pull back. He was saying: ‘My life is too crazy now. I don’t want to do any more videos'. I was thinking: ‘Fuck, we’re going to blow this'.

“It went counter to everything I ever believed. But it also made sense in the long run because we’re talking to one another now. That’s one thing I think about Ed: I really respect his vision. In the long run he was right.” – Mike McCready, Pearl Jam

October 1993: Pearl Jam’s second album, Vs, has been out for a week. It has sold 950,378 copies – more than the rest of the records in the Billboard Top 10 put together. The reviewer in Rolling Stone magazine has written: ‘Few American bands have arrived more talented than this one… Like Jim Morrison and Pete Townshend, Eddie Vedder makes a forté of his psychological-mythic explorations.’

The band have just received four MTV video awards for songs from their first record, Ten, which itself is the eighth-best-selling album of 1993 despite being two years old.

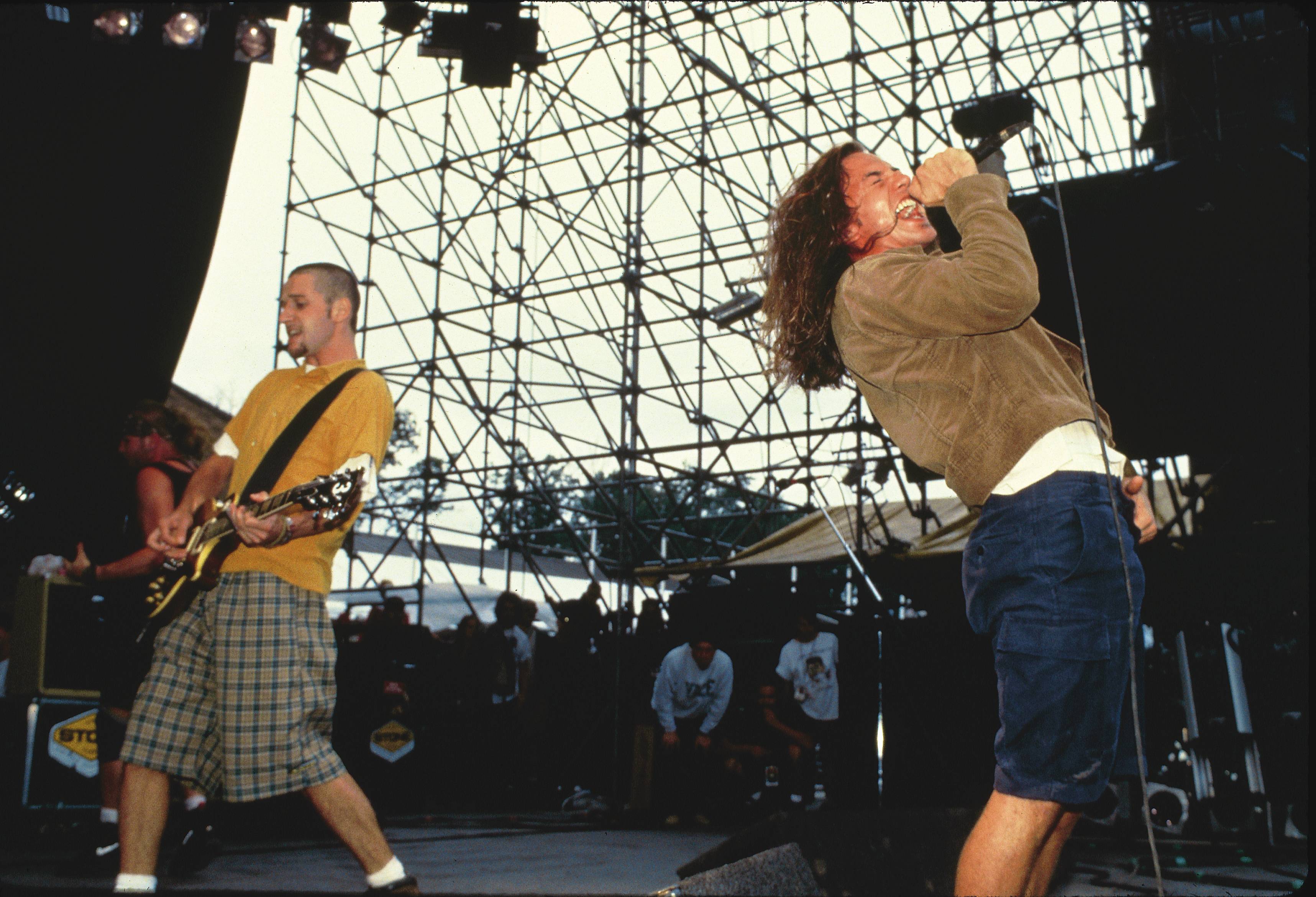

But it’s not just about the numbers. Pearl Jam’s words and music deal with some dark emotions and they provoke a deep affinity in their followers. Booked as a support act on the 1992 Lollapalooza tour under Red Hot Chili Peppers, Soundgarden and Ministry, they go on stage at 2.30pm. Over 30,000 people turn up to watch them play for half-an-hour. The organisers want to move them higher up the bill. Pearl Jam say no.

When the tour ends, bass player Jeff Ament returns home to his apartment in Seattle. Sitting in his local coffee shop, he wonders why everyone is staring at him. When he realises it’s because he’s a member of Pearl Jam, he begins spending his spare time in Montana.

Singer Eddie Vedder comes straight off the Ten tour, and has to write and record the Vs album. He is the only member of the band currently in a long-term relationship. He realises that the music has become more important than the relationship, and he knows it shouldn’t be. He finds it difficult to communicate this to the rest of the band.

Guitarist Mike McCready has been waiting his whole life for a chance to be a rock star. He grew up wanting to be like Paul Stanley and Joe Perry. When Duff McKagan, a friend from high school, moves from Seattle to LA, Mike decides to follow with his band, Shadow. By the time they arrive, in 1986, Duff’s band, Guns N’ Roses, are doing pretty well, and the whole of LA has back-combed hair and is wearing spandex trousers. Shadow join in, enthusiastically. McCready hangs out at the Cathouse and Club Lingerie, handing out fliers with the other wannabes.

Shadow last a year or so before McCready becomes ill with Crohn’s Disease and returns to Seattle, where, sick and disillusioned, he quits playing guitar. He flounders for a year or two, and is working in a restaurant when his old friend Stone Gossard calls and asks if he’d like to play on a tribute record for the singer in Stone’s band, who has just died from a drug overdose. McCready’s last shot at being a rock star has arrived.

Stone Gossard and Jeff Ament have been part of the Seattle scene forever. One of their early bands, Green River, release the first record on the Sub-Pop label. On the back of Green River, Sub Pop become successful enough to sign Nirvana and fund their debut album. Stone and Jeff’s next band, Mother Love Bone, sign a major-label deal just before Nirvana do, but the band folds when singer Andrew Wood overdoses. When the chance comes again, they’re desperate to take it.

After Ten goes triple-platinum and Vs is released, Pearl Jam make the decision – some of them reluctantly – not to make any more videos or promote themselves heavily to the press. Instead they go on tour, and write and record their third album while on the road. Its producer, Brendan O’Brien, calls the sessions “a little strained – and I’m being polite. There was some imploding going on.”

Pearl Jam have reached their fork in the road…

Summer 2009: Pearl Jam still exist. In fact, they more than exist, they’re flourishing. They have a new album in the can, and they are looking forward to marking their 21st anniversary in 2011. To understand how well they’ve survived, how good was the decision they made when they came to that fork in the road, look at the list of bands who occupied the same headline space back in 1993: Soundgarden, Nirvana, Alice In Chains, Mudhoney, Hole, Tad, L7, Screaming Trees, Stone Temple Pilots… These are names from another age.

Pearl Jam’s tried and tested survival techniques remain intact, too. This is their first formal interview with Classic Rock, and, aside from a few days of press, they will not be doing too many more with anyone else. They have entrusted the making of their 21st anniversary movie (Pearl Jam Twenty, released in 2011) to Cameron Crowe, a director they first worked with on the film Singles in 1992. They have retained the same manager, Kelly Curtis, for their whole career. When they required a new drummer after the departure of Jack Irons in 1998 they got Matt Cameron, formerly with Soundgarden, and a man who had lived through the same formative experiences that they had. There is safety in shared history.

They have even returned to Brendan O’Brien as producer of their new record, a tight yet expansive 38-minute album titled Backspacer. It’s the first time they’ve worked with O’Brien since the dark days of 1994’s Vitalogy.

- Pearl Jam - How Death Brought Ten To Life

- Sport: Eddie Vedder

- Alice In Chains: Seattle scene was magic

- Pearl Jam donate $300,000 to aid Flint water crisis

For Pearl Jam there is a feeling of having made things right, of having acknowledged the lessons of their past, of having found their place in the world.

“I don’t think I could have handled it if I was a big 70s rock star,” says Mike McCready. “Those are all the myths that I grew up believing, listening to Van Halen or all the guys I grew up with…”

Not that he didn’t give it a go. McCready spent 1993 and beyond embracing the rock’n’roll dream. “I partied lots, I drank a lot and lived the lifestyle. I loved it and hated it. I did it till it went fully south on me, and ended up getting clean. And I have been for a long time, and I’m very grateful for that. But that’s how I handled it. I was the one in hotel rooms breaking things.

“I realised we were a really good band, and we were treated as a great band and that turned into something else that was bigger than any of us could really put our fingers on. I didn’t try and figure it out, I just went along with it. Whenever there was something to do at a party, I went out and did it. I bought into that lifestyle and it was fun for a while and then it turned into a complete nightmare.”

Long before it was a nightmare for Mike, it was a sombre reality for Eddie Vedder. It became known that the lyrics to Alive, Pearl Jam’s biggest song, closely followed the path of his real life. Eddie grew up thinking that his stepfather was his real father, only discovering in his late teens that he was not – the same time he found out his real father was dead. His angst struck a chord with millions of kids. They loved Pearl Jam’s music, but it was Eddie who embodied it for them, who spoke to them and for them.

It was Eddie that Time magazine put on the cover of their October 25, 1993 edition, even though he’d refused to talk to their journalists. It was Eddie who coped with the stalker about whom he would later write the lines: ‘I return to find an open door/Some fuckin’ freak who claims I fathered by rape her own son/The last I heard the freak was purchasing a fucking gun.’ It was Eddie in the long-term relationship; it was Eddie who told the rest of the band that he couldn’t do this any more; it was Eddie who came across like the miserable bastard who didn’t like fame or adulation or attention or money. It was Eddie and Kurt Cobain who became the faces of the Seattle Scene for the parts of America that wouldn’t otherwise understand what the Seattle Scene was. It was Eddie about whom people asked: “If you don’t want to be a rock star, why are you in a rock band?”.

The idea that we didn’t want to be famous was kind of BS in my mind,” sayds McCready. “I’d been trying to make it in bands in Seattle since I was 11. I was in Warrior, I was in Shadow, we did demo tapes, we were a metal band, all this stuff. In the early days, late 80s, Seattle was just rock bands playing all over the place and putting out records. Green River was, Tad… Everybody was trying to play music and make a living. The image of the anti-image or whatever was just how people were up here. I don’t think we were trying to get rid of the whole 80s hair-metal thing. That wasn’t calculated. Personally I was part of that scene. I moved down to Los Angeles and we tried to make it; I used to wear spandex.”

But it wasn’t so much the rock star lifestyle that was affecting Eddie. Rather it was the expectation that came with the job. That Time magazine cover carried the line: ‘Angry young rockers Pearl Jam give voice to the passions and fears of a generation.’ No one had ever written anything like that about Bon Jovi.

“It’s what happens when a lot of these people start thinking you can change their lives or save their lives or whatever,” Eddie says. “It creates these impossible expectations that in the end just start tearing you apart.”

The Pearl Jam dynamic was about to change forever. The band had begun as Stone and Jeff’s band. They’d formed it, they’d found Mike and Eddie, they’d written the music that became the songs on Ten. They were the ones who’d been in Green River and Mother Love Bone, who’d carried on when their singer died, who’d managed to get another record deal. But, as Eddie became the focal point of the group and its most famous member, he gradually assumed the leadership, too.

“We never really seriously considered giving up,” says Eddie. “I just think that the idea was to try to get our hands on the steering wheel and, you know, not take it off into a ditch, but definitely find an off ramp. ‘Let’s just drive on some side roads for a while or let’s slow down’. The vehicle wasn’t built for speed. And definitely, you know, I think at some point it was like looking around and saying: ‘Who is driving this fucking thing?’. Or we thought we were driving, but we’re ending up in places that we never thought we would go.

“And so: ‘Do we wanna be here? No. Let’s get the fuck out of here. Who is gonna drive? Let’s get these other hands off the wheel, let’s grab the wheel. Foot on the gas, foot on the brake, whatever, but let us drive this thing’. We didn’t wanna just have a record or two and not know what could happen after that, you know. It is astounding to me how bands don’t last. And it doesn’t seem that hard to us, but it must be, because this just doesn’t happen that often.

“When we did Ten, Stone and Jeff were pretty much leading the way on that,” Mike says. “As that record blew up and we got huge, Ed slowly emerged as the leader for the second and third records and from then on. We try to make it as democratic as possible, but certainly it leans a lot towards Ed’s vision.’

Deconstructing success is not a simple process. Turning down money, fighting Ticketmaster (as the band did for three years), making albums that – perhaps subconsciously – sounded less and less like the big-hit debut, selling fewer and fewer copies of each one, arriving at a position where, as Rolling Stone magazine wrote in 2006: “This is a band that have spent much of the past decade tearing apart their own fame.” All of that takes its own toll.

“There were times when we were fighting, there were times when we were really getting along well, there were times when we weren’t talking to each other,” says McCready. “There were things that happened that, had we not pulled back at that time, we would have broken up. There were some very tense times.”

What’s been left behind afterwards is a band with an entirely new hierarchy. Vedder –who the rest of the group call Ed rather than Eddie – is now its defining figure, both culturally and artistically.

“I knew Pearl Jam was always a real positive environment to be in compared to Soundgarden,”says Matt Cameron, who watched Pearl Jam from the outside before he joined. “Soundgarden was always a real negative environment. The music that we made in Soundgarden came from a darker sort of place. It was awesome and I love it and I’m very proud of it, but Pearl Jam has a better inter-working relationship.”

“We all kind of have our single ways of doing things,” McCready says of the way Pearl Jam operate now. “Ed’s the leader in a way. We bring our things and he sings over the top, but I think he’s caring enough and interested enough in other people’s songs that he will listen to them and put ideas to them. He could certainly write every song on the record. And that would suck, I think, for us. I think they’d be great songs, but for us band members it would suck. But we’re lucky we can all still write music and he’s into it. He trusts us.”

- Soundgarden album ‘off to very good start’ says Matt Cameron

- Soundgarden: the story behind Jesus Christ Pose

- Kurt Response: Steve Gullick on his new book ‘Nirvana Diary’

- Secret Layne Staley tracks could surface, says Seattle audio engineer

“He’s the artistic director of the band, there’s no question about that,” says Stone Gossard. “We’re effective because of his instincts. But as the artistic director he’s saying: ‘I need a Jeff Ament vibe, I need a Stone Gossard vibe…’. He’s looking for material from all of us. He doesn’t just approach the band as: ‘I’ve got all of this figured out and you guys just follow my lead’. There’s a lot of other players more suited to that. He wants our combination to drive this thing. You let him drive and trust his instincts. He’s a band guy. He likes bands.”

“What the band did this time,” Vedder says of the new record, “which was really nice, is that they went and played without me for a week in Montana. They wrote and played… they didn’t even tell me they were going, which I thought was extremely kind, and didn’t even make me think like: ‘Well, I should try to get there, maybe for the last two days’. They just went and worked for a week – and I think Brendan was there for a day or two – and what they came back with was songs, you know, as opposed to riffs. That started the process, so it made my job just a lot easier, because riffs are tougher than songs. They actually had arrangements to them.”

“Ed is incredible in the way he can draw creative information out of all of us,” Stone says. “It’s not every rock singer that’s as good as Ed. He wrote five or six songs on the record, and clearly is a great writer based on his solo record [2007’s Into The Wild] He could do it all if he wanted to, but he really chooses to participate in this thing and he really wants people’s input.

“The empowerment all of us feel about him drawing us out and for him to feel excited about our brand of rock – we have a unique take. Certainly Jeff and Mike and I, we’re not professionals… We have something we do together, and usually it’s the best when it’s three chords and any knucklehead in a bar could play it. But he puts them together in a way that sounds right, and his voice and his lyrics and his storytelling over the top of our groove and our energy makes it something special. You have to embrace your weaknesses as well as your strengths. He’s willing to subjugate his ego in terms of drawing out information from everyone. Even he is ultimately at the whim of what we are capable of as a group.”

For Pearl Jam the last year has been a circular one, in which both ends of their career meet up. Alongside the recording of Backspacer, they and Brendan O’Brien undertook a reissue of Ten, a project that saw O’Brien remix the record’s 11 songs for re-release alongside the originals. It was an opportunity for them to look backwards as well as forwards.

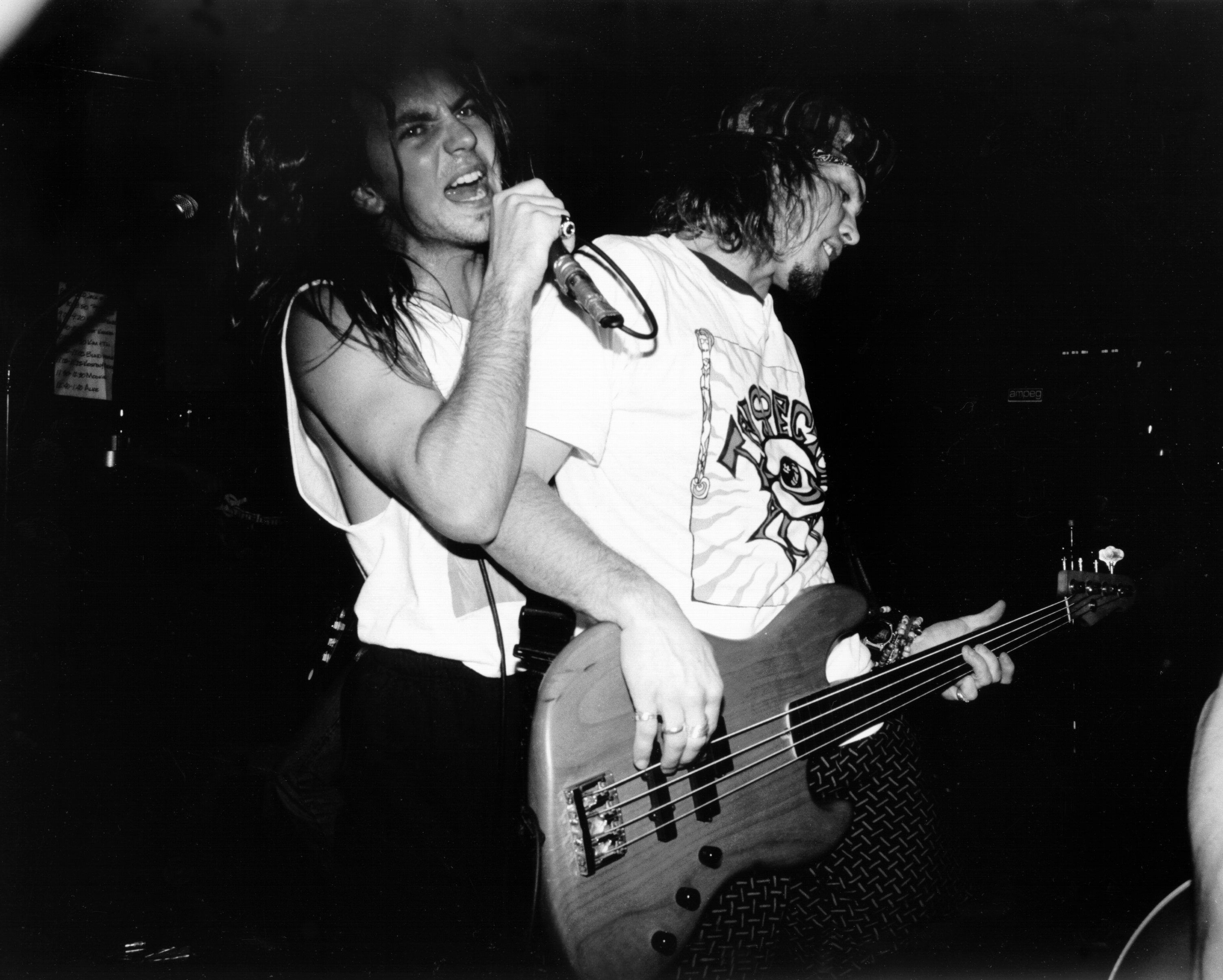

“Hearing the reissue, it felt that raw, like when were opening up for Alice In Chains, when we were Mookie Blaylock going up and down the West Coast. It felt like that,” McCready says. “We had 30 minutes, and we had those songs and a Beatles cover, and we had to hit it hard. It reminded me of those days. Looking back, Ed handled it perfectly, because we’re still around. Now we’re older and we have families and we love doing our art and playing music, having fans out there, being able to talk to Classic Rock magazine. I think he handles it better now. We all do. We’re older and we’ve been through the ringer a little bit.”

“Without wanting to sound trite, I think we’re the best band we’ve ever been right about now,” agrees Vedder. “We might not be throwing our heads into drum kits, but slightly… you know, slamming torsos into amps. But it’s still pretty aggressive when we get out there.”

“This band likes rock’n’roll,” Gossard says. “We revel in playing it, more so now than ever before. I don’t think we enjoyed it as much as we could have in the 90s. It wasn’t nearly as much fun as it is now.”

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #137.

For more on Pearl Jam and Jeff Ament, then click on the link below.