Having released their 11th studio album, Love Over Fear in 2020. Prog talked to the band's Nick Barrett about the highs and lows of Pendragon’s career and finds out why he considers the band to be an open marriage.

On Who Really Are We?, the penultimate track of Pendragon’s new album Love Over Fear, Nick Barrett sings, ‘To my mind it’s a miracle we got this far.’ He’s talking primarily about the human race and humanity’s capacity to be its own worst enemy. But it could also apply to Pendragon themselves – a band that formed at the height of punk’s popularity (and the beginning of prog’s long residency as the love that dared not speak its name), who missed out on the success and profile the neo-prog scene promised. The band also had to deal with poverty, bitter divorce, label and management turmoil, and see-sawing fortunes as well as the regulation line-up changes, yet they managed to hold their own creatively and commercially. Still retaining a strong following abroad, Pendragon endure, with last year’s belated box set, The First 40 Years, offering a part-live, part-remixed collection of songs from their preceding 10 albums.

Barrett recently relocated to the coast of Cornwall near Bude, where he and his girlfriend Rachel run a small but highly rated B&B, The Barn (“surfers and bikers especially welcome”), which benefits from stunning views of the countryside and out to sea at Widemouth Bay.

Those new surroundings seem to have had a strong influence on Love Over Fear, which is quite often effusive about the revitalising effects of being closer to nature.

“Peter [Gee], our bass player, said, ‘You can almost feel the sea’,” Barrett reveals, “and I definitely think the album has an uplifting feel. There is of course some darker underlying stuff, but overall it’s got a more uplifting feel.”

That’s certainly true, from the upbeat rhythm that opens the set with Everything to the Waterboys-esque folk-rock of 360 Degrees, in which he asserts ‘I don’t care if I’ve got seaweed for hair’ and ‘all aboard the carpe diem, love over fear’. On Water, the keen surfer also writes ‘I go down to the water when the wolf is at my door, she wraps her waves around you and makes you feel loved once more.’

The album culminates in Afraid Of Everything, urging us to ‘live the moment to the last’.

“It’s about how life is not all about having a pension to always keep this safety net. It’s about embracing the fear. With surfing sometimes it’s pretty scary when you go off the top of a bigger wave, but you have to find a way of making that work.”

All of the above are enveloped in some of Barrett’s most irresistibly anthemic melodies, punctuated by some strikingly emotive guitar work, along with some less conventional instrumentation, such as violin and organ.

But there’s also an undeniable yin to the yang of those songs, which is the frustration expressed at a world increasingly governed by (as Barrett sees it) ill-informed social media-based opinions and a culture of self-obsession.

Barrett’s views have always been difficult to pin to any particular point on the political spectrum. On one of his most outspoken compositions, 2011’s This Green And Pleasant Land, he raged in an apparently left-leaning fashion, at how ‘hospitals are just another business plan’ and old war heroes were dying alone in cold flats while ‘British Gas and their shareholders are getting richer, getting fat’. But elsewhere in the same song he made the kind of faintly ludicrous complaints that are beloved of right wingers everywhere: ‘Christmas is a word you can no longer say’ (obvious response being: “Well, you just did!”) and ‘It’s not legal to say what I think anymore because I don’t believe in Sharia Law.’

Meanwhile he prides himself on a wide range of reading from Solzhenitsyn and Russian history books through to the, erm, controversial works of David Icke.

But don’t tag him, folks – this is a man who puts his faith in the printed word far more faithfully than the forked tongue of social media. As befits a man who’s been cutting against the grain since he formed Zeus Pendragon all those years ago. Which is where we begin our conversation.

You spent your formative years in Stroud, Gloucestershire. How was that for an aspiring musician?

It’s very, very West Country, and a hard place to get a band off the ground. I remember going to the bank and asking for an overdraft. He said, “What for?” And I said, “We’re a band, we want to make a record.” He said, “Oi dunno much about records… If you wanted a cowshed, I could probably ’elp yer!” I thought to myself, this is not gonna be easy!

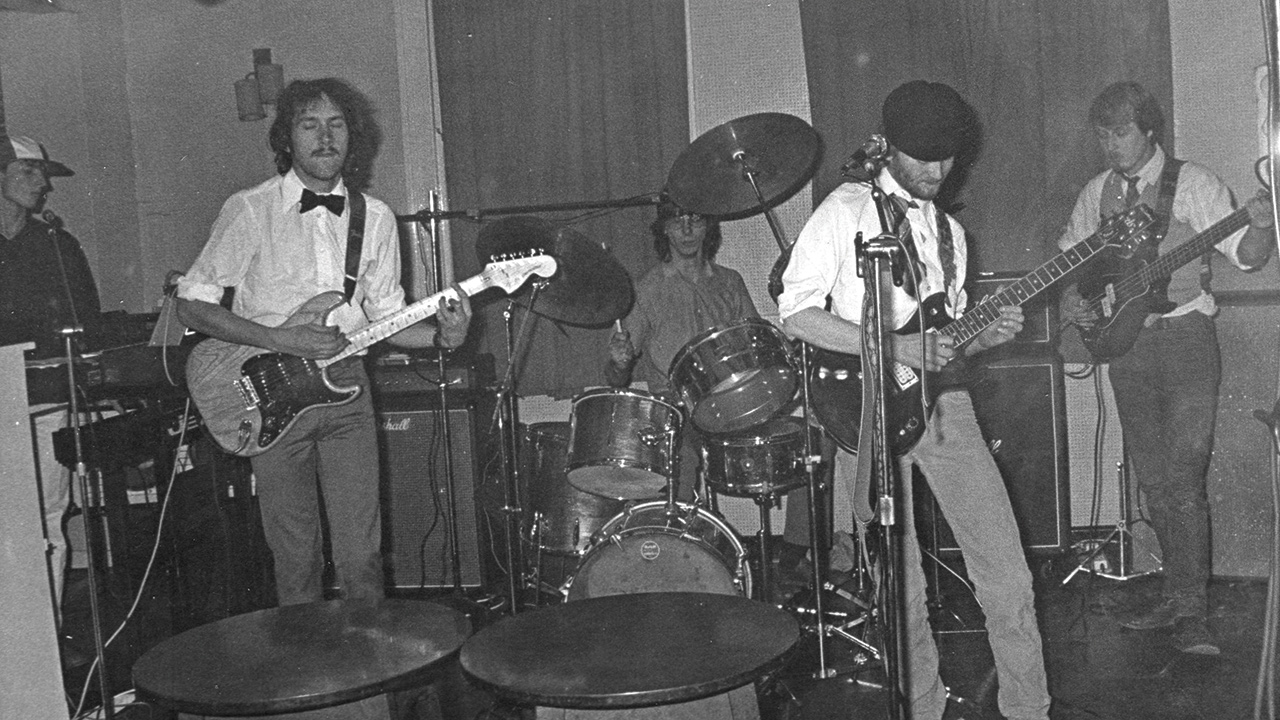

You formed Zeus Pendragon in 1978, left school at 15 and played your first gig the same night…

I just couldn’t imagine anything in life could be better than that. I came home from that gig and I just couldn’t sleep, I was going over every single second of the gig. One of the happiest moments of my life.

The story goes that you burned your school books that day too…

Yes, sir. I wasn’t really a school person. I told my careers teacher, “I want to be a rock musician, a guitarist.” She said, “Are there any courses you could go on to do that?” And I said, “Keith Richards didn’t go on any college courses!” So I was in the no-hope bucket.

Was 1978 a weird time to be playing prog, just as punk was going overground?

It was. With some of my mates it was like Invasion Of The Body Snatchers. Their souls had been taken! One guy would just live for Yes, everything was about them and suddenly within a week he was like, “Oh, I hate all that shit! I’m now into the Dead Kennedys.” Look, hang on, Dave! Are you in there?! Dave, don’t let this imposter take you over! I thought, no, I’m sticking to this, I love Genesis and that’s final!

It must have been tough to get the gigs then?

Yeah, and almost every gig we played was completely inappropriate. I remember one of the first ones we did outside the Stroud area was at Redditch College. It was a mixture of punks, skinheads, a few metal kids, two prog-looking people, and no one knew who we were. There was an enormous window about 15 foot by eight foot at the front of the foyer of the college and someone smashed that. It was absolute chaos, and everyone hated us. But we plodded on.

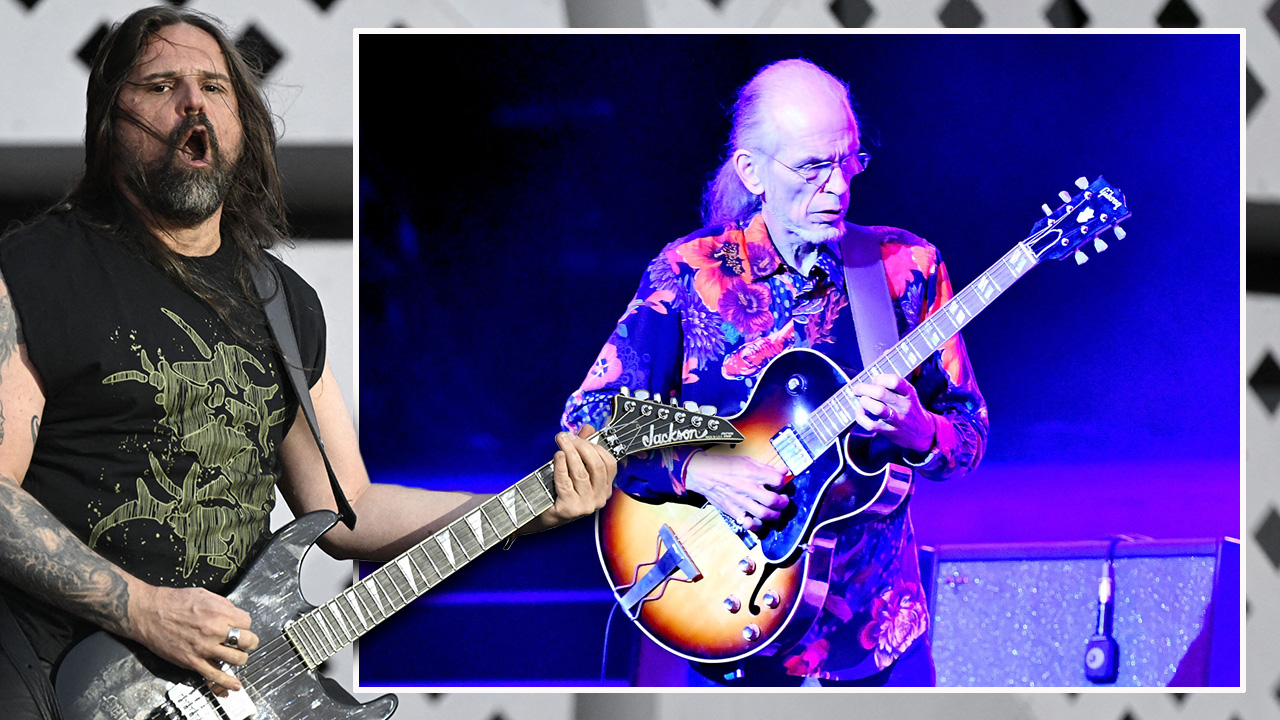

Then around 1982, the neo-prog scene began to take shape. Was that the first time you felt any belonging, or was that scene quite competitive?

Funnily enough, it was both. When we played with Marillion for the first time in London we couldn’t believe it – there were 500 people going completely nuts, with the greasepaint on like Fish, jackets with all the bands on, and yet there were also people there with mohawks, and it was really quite something. With other bands doing a similar thing we did feel part of something, and that did grow into competition – not with Marillion because there was no contest: they were signed to EMI and they obviously did brilliantly. It just pushed you a bit harder. If someone got two gigs you’d try to get five gigs.

Marillion’s manager, John Arnison, then signed you to his label Elusive for the Fly High Fall Far EP (1984) and your debut album, The Jewel (1985). How was that experience?

Looking back on it, you could look at what we signed and think, “This contract’s terrible, you’re never allowed to breathe again!” But he never really stuck to it and it’s incredible he took a risk with us to do that. Without that we’d have never got a leg up to make any records. So we’re still grateful for all the help we had.

Then you made Kowtow, by way of showcasing both sides of your music: accessible radio-friendly rock and adventurous sounds.

We always had a commercial side of our sound, and I’m proud of that. It didn’t feel like a compromise – it was just another thing that we do as well as the long instrumentals.

But you ended up towards the end of the 80s without a major label deal and, like much of the neo-prog scene, at a pretty low ebb…

Well, we couldn’t get a record deal. We were feeling pretty sorry for ourselves, management decided they didn’t want to do it anymore, it was incredibly demoralising. We had no money, no record deal, a whole load of debt, we were renting a room, driving a crappy old Ford Cortina with a burnt-out head gasket,

no girlfriend, it was just a shit sandwich. You’d be standing on the hard shoulder at three o’clock in the morning, freezing to death with a broken-down van, no money for food, and you’ve got a gig to get to in Manchester then another one in Southampton, and you’ve got to make it work.

But I had Clive [Nolan, keys] and Peter with me, and we were all pretty determined. So when one was down the others would say, “Come on, let’s give it another go.”

You look back on these problems and they’re actually opportunities. When we couldn’t get a deal it also forced me to say, “Right, we’re not getting any interest, let’s start our own record company.” And it was the best thing we ever did.

And while the early 90s were a struggle for a lot of prog acts, you feel otherwise, don’t you?

Yeah, well when we released The World, we were thinking we’d pay off the

bills and see what happens but we sold 12,000 in a week. We started

to get some money coming in, we could advertise, tour more, we could start our fan club, The Mob, and distribution got better. For us the early 90s were just magical.

Was that partly a result of looking further afield?

Yeah, I’d be faxing people overseas in the middle of the night because it was cheaper. I’d decide, “Okay, I’m going to hit Japan tonight.” And I faxed all these people all night long, went to bed and came back the next day, and maybe there might be one person faxing in return saying, “We’ll have a box, sale

or return.”

Evidently, quite a few unlikely fans came out of the international woodwork…

Yeah. In around 1994, on the Window Of Life tour, we got a call out of the blue telling us an agent in Poland wanted to put Pendragon on over there. It turned out our records had been smuggled in under these lorries throughout the 80s and played on the radio so we actually had quite a big following over there. We built a good following in France through contacts there, and the same in South America. Within two years we’d sold out nights in Buenos Aires and Chile.

And by the time of 1996’s The Masquerade Overture you were doing pretty well, weren’t you? In fact, you have previously talked about that period offering you a taste of the rockstar lifestyle: girls, Jacuzzis, a big house in

the country…

Yes, sir.

Aaaand then you got divorced and lost the house…

At the time it was a complete and utter nightmare, but you just have to carry on. And it has fuelled me to keep being creative.

So it seems, if we count Not Of This World (2001) as your heartbreak album…

It is, and it’s one of my favourite albums. If you breeze through life, your will to create just dwindles. The inspiration to think about life, the universe

and everything is less pressing.

The motivation for older musicians becomes making money, and the creative impulse sinks to the bottom.

You also began to introduce some more contemporary sounds on the albums that followed – 2005’s Believe, Pure in 2008 and Passion in 2011 – from nu-metal to hip-hop. What inspired that development?

My son and I are really into motocross and when he was very young he’d get all these motocross videos for us to watch. Some of the music on it was American college rock, emo or nu-metal, and you know, the singers aren’t classic vocalists, but they had this energy and the sounds of the songs were so melodic. Bands like A and Trapt had these fantastic songs with a metal edge. So on stuff

like Comatose (II. Space Cadet) on Pure that’s one of the things that’s come out: this grungy, punky edge.

Inevitably, it got some polarised responses from fans…

Yeah but then I used to hate opera, and that was my problem, not opera’s. I remember when The Lamb Lies Down… came out, I just thought, “What the heck is this? These two albums, it’s just so wordy I can’t get my head round it!” But I started to play it again and again and after the penny dropped listening to The Carpet Crawlers, I realised it was the best music I’d heard in my life. I mean, so many people say, “I hate jazz!” That’s their opinion but they’re making their world much smaller.

This album and 2014’s Men Who Climb Mountains have been highly melodic, anthemic affairs. And this one even seems to have a strong back-to-nature theme…

I never really pick a theme and think, “I’ll make an album about that.” It’s not a concept album as such. It just slowly unfolds maybe from one or two lyrics. The song Water, for instance, started as one or two words. I think I came up with: ‘This is my element, time is irrelevant’ and it went from there. When I moved down to Cornwall I stood where we live, and I thought, “Well there’s sea there, there’s fields there, there’s sky there, blue and green everywhere around – it’s an incredible thing, and… you don’t get that in Swindon!” It inspired the song 360 Degrees, which just had to be an uplifting thing.

At the same time, there’s another more topical theme of the malicious influence on modern life of the internet and social media. Truth And Lies,

for instance, seems to reference a mendacious modern age of fake news and “alternative facts”…

It just struck me the lack of interest in the truth in things is just monumental at the moment. It’s incredible people don’t seek it. And yes, the song Everything

is about social media, people who know everything but know nothing. Everything seems to be trial by Facebook and people never go away and do any research. I say things to people like: “Donald Trump is the first Republican president to hold up the rainbow [LGBTQ] flag” [in 2016. His administration has since denied embassies the right to fly the flag – or so it says on the internet] and people are horrified, they don’t want to believe it. Some sort of alternative way of thinking is out there, but they don’t want to do their research. So that’s where Truth And Lies becomes an inspiration and I want to write about it.

But I’m glad the lyrics are cutting through because you never know, really. Me and Clive used to talk about “Dusty Bin” lyrics. Do you remember Dusty

Bin from the TV show 321 [who would offer ludicrously impenetrable cryptic clues to baffled contestants]? With some lyrics you just couldn’t have a hope

in hell of unravelling what they are about.

Another theme seems to be the era of self-obsession… ‘Don’t fill your snowflake head with how beautiful am I.’ ‘Snowflake’ is a bit of a loaded phrase – what does it mean to you?

This is a big subject so it’s hard to say things in a few sentences. People react very emotionally to things the further away from the truth they get, and because of that emotion I think people are overly sensitive to things. They can’t deal with their own lives.

I notice from the Musicians Union I’m getting tons and tons of mailouts about mental health and how you can talk to people, and sexual harassment… there’s nothing about getting musicians a better deal on Spotify which is what we really need. I mean, I suspect one of the reasons why they’ve got mental health problems is ’cos they’re not getting paid for their work!

I think there’s an awful lot of narcissism created out of social media. Everyone’s preoccupied with “What’s everyone saying about me today?” It’s become absolutely intolerable.

How different are you now as a creative person than you were when Pendragon started?

I get more and more immersed in doing things properly, more intently and more seriously. Whereas when I was 25, I’d sit around smoking and doing bugger all. This music has taken nearly six years, and I could spend a week working a keyboard sound and then decide I don’t like it and bin it. That phrase “youth is wasted on the young” seems true to me; when I got the vinyl of this album I must have listened to it 50 times listening to every single second checking it was as good as it could be. I’d go back to Karl [Groom, producer] and say, “Can we move that hi-hat one decibel? It’s not quite right.” I have to give it absolutely everything.

Meanwhile, Pendragon continues as something of an open marriage, given that Clive is still among the hardest-working men in showbiz, with Arena, the Caamora Theatre Company, solo projects and what have you. How does that work?

Basically, it’s live and let live. You can become the jealous husband or you can get on with it. We get a bit old and angry with each other – “I didn’t know you were touring then, you never told me!” – but we usually just work it out. “You going out April, May? We’ll go out October, November.” It’s worked itself out over the years. And this is the reason bands like Pendragon have survived. People feel they have other creative outlets somewhere else. When Clive first joined Pendragon [in 1986] I said, “Look, we’re not really looking for any more writers here.” And he said, “That’s fine by me.”

We all realise how frail this whole existence is. We realise how important it is for Pendragon that these other bands have some way of surviving still. It’s important that there’s a genre and there’s a number of artists doing it. If there was just one band there wouldn’t be a Prog Magazine! [Laughs.] So it’s important that there’s a bit of a brotherhood going on. And it’s a great, fascinating thing to be part of.