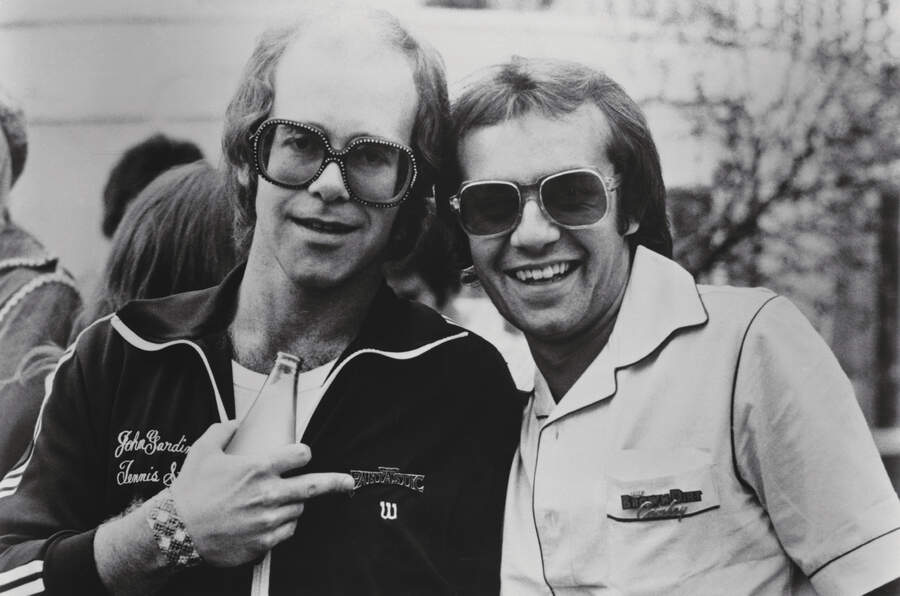

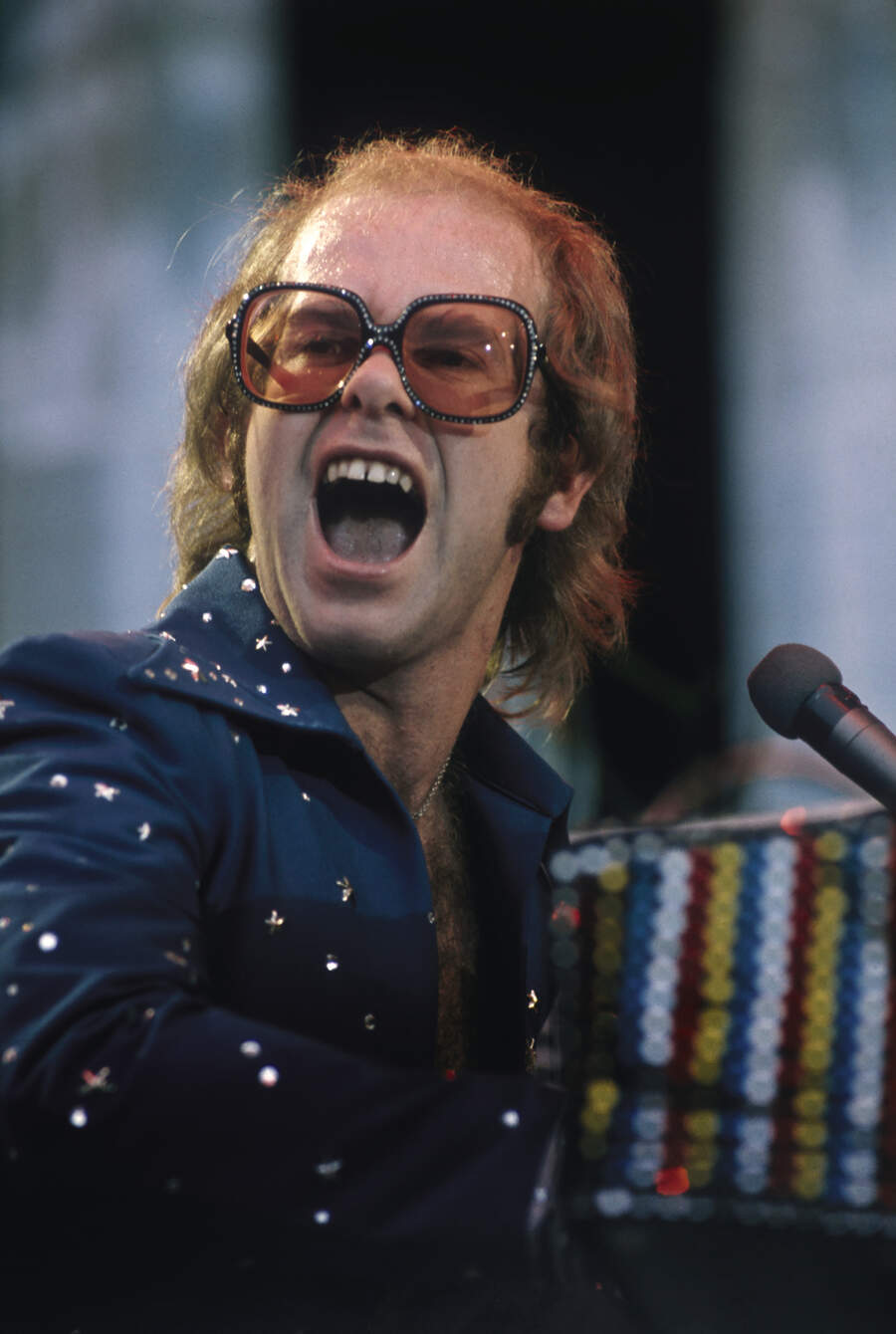

In 1975, Elton John was the biggest rock star in the world. His last four albums had all gone to No.1 in both Britain and America and he’d notched up a dozen US Top 10 singles, including three No.1s. His most recent chart-topper, Philadelphia Freedom, was inspired by his new friend Billie Jean King, the American women’s tennis legend who had beaten Bobby Riggs in the famous Battle Of The Sexes match the previous year. King was now part of the Philadelphia Freedoms, a newly formed professional tennis team.

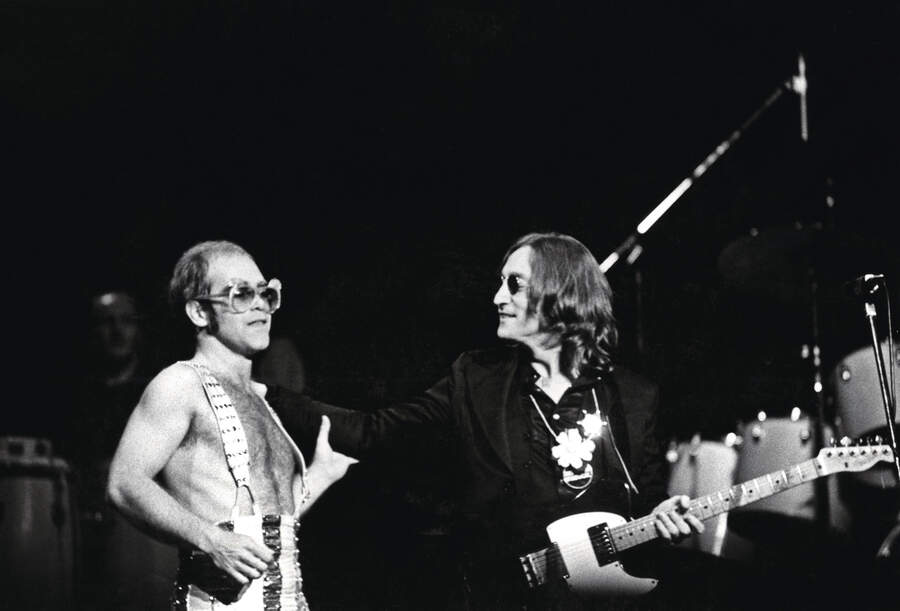

Elton’s previous single had also gone to No.1: Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds, featuring backing vocals and guitar from another new best friend, John Lennon, who’d written and sung it in The Beatles.

Elton had a lot of new friends now, heavyweight celebrity groovers like Elizabeth Taylor and Cary Grant; Michael Parkinson and Miss Piggy. He was enjoying camp tabloid ‘spats’ with old tarts from the before-days like Rod Stewart and Marc Bolan. Cat fights with David Bowie, who believed Elton ripped off Space Oddity for Rocket Man (which Elton’s lyricist Bernie Taupin kinda had). Heart-to-hearts with Dick Cavett and Freddie Mercury.

It was his relationship with Lennon that really mattered, though. It was he who inspired Elton to fork out for his Windsor mansion, Woodside, after a visit to Ringo Starr’s palatial residence, Tittenhurst – formerly owned by Lennon – convinced him that a man of his stature should have a country mansion of his own.

When Philadelphia Freedom hit No.1 in March ’75, the more interesting conversation concerned not the Billie Jean connection nor the copycat Gamble & Huff production. What grabbed most attention was the B-side, a frenzied live recording from November ’74 of Elton and Lennon belting out early Beatles song I Saw Her Standing There – Elton holding down the McCartney vocals easily.

The two had become buddies, bonding over cocaine and a shared sense of bawdy English humour, during hot summer night sessions in New York for Lennon’s fifth solo album, Walls And Bridges. Elton played keyboards and sang harmonies on the track that would cement their musical kinship, the driving Whatever Gets You Through The Night. Elton had encouraged Lennon to release it as a single, betting him it would go to No.1. Lennon, who’d never had a solo chart topper in America, laughingly took the bet, agreeing that if he lost, the reclusive ex-Beatle would make a guest appearance at an Elton concert.

After Whatever Gets You Through The Night became Lennon’s first – and only in his lifetime – solo No.1 single in the US, he was on stage with Elton in front of a deliriously disbelieving audience at Madison Square Garden, his first live appearance for two years.

Things were running so hot for Elton John that year that his latest album, Caribou, had only just arrived at No.1 in July when he and Bernie Taupin returned to the Caribou Ranch studio (after which the album had been named) in Colorado to begin writing and recording their next album.

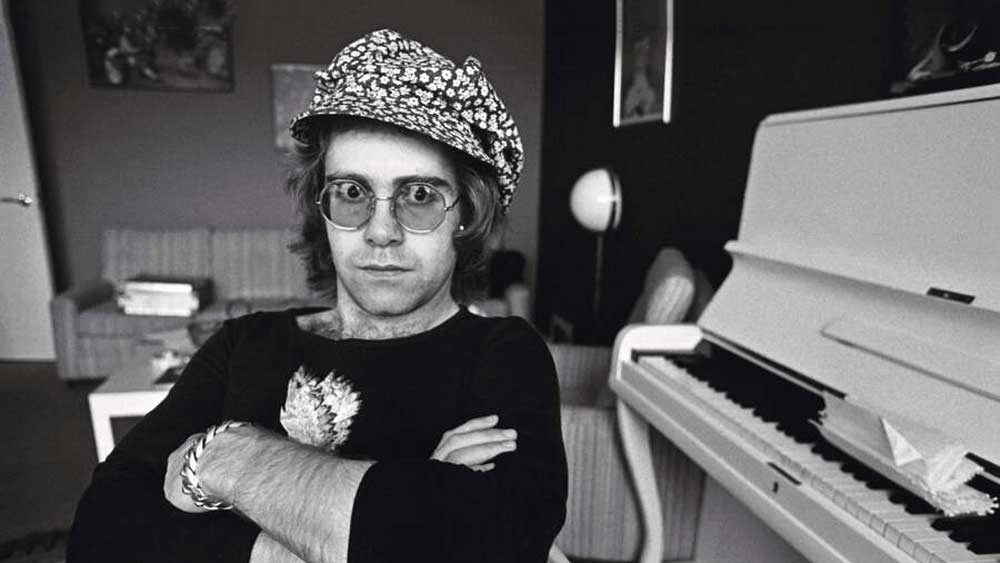

Some of the music had already been worked out during the five-day trip from Southampton to New York on the ocean liner SS France that Elton elected to make (he’d recently been gripped by a cocaine-induced terror of flying). Elton spent his lunchtimes working at the piano in the ship’s music room. However, the ship’s resident pianist, a classicist, resented this intrusion so much that she made a point of playing on the deck above him, battling to drown him out.

Back at Caribou in August, the serious work commenced on what Elton and Bernie now determined would be their magnum opus: a concept album on the level of other great 70s conceptualists like Pink Floyd, The Who, Genesis and David Bowie.

Despite selling more records than all of them, Elton and Bernie were acutely aware that they didn’t command the same level of respect as contemporaries like Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell, whose work always got the red carpet treatment, even when it disappointed. Elton and Bernie came up with Daniel and Your Song and Rocket Man and Candle In The Wind, and so on and so on.

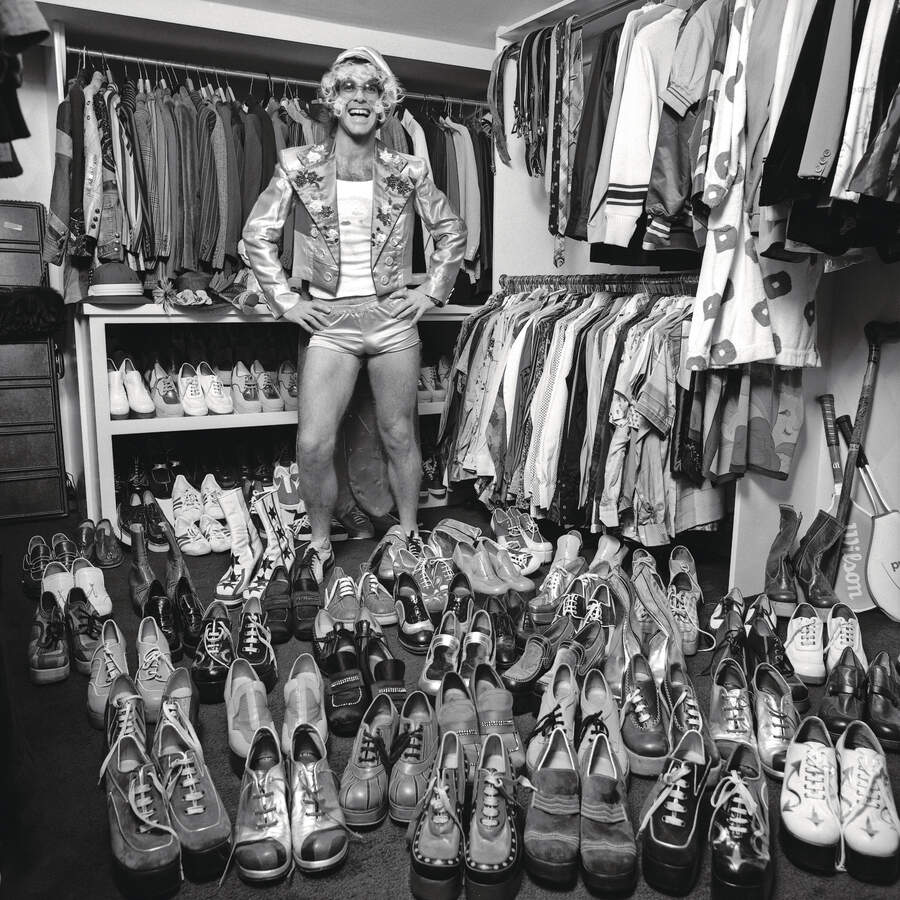

With both men now resident far over the rainbow, they already had everything you could dream of. But they were doing Scarface levels of cocaine and had begun to glimpse immortality. The kind that Neil Young had. Now they craved that too. But Dylan didn’t crocodile-rock on The Muppet Show; Joni didn’t pretend to be black on Soul Train. Young didn’t go on stage dressed as a cat, in sunglasses, with cute ears, and start playing piano. Lou Reed was dramatising Brando-style shooting heroin on stage.

Elton and Bernie knew they needed something epic to move the critical dial on the tragi-comic singer in the oversized clown glasses and gold nine-inch platform boots. Elton considered growing back his Honky Château beard.

Then Bernie had it: the story of their own journeys from hopeful nobodies to spangly superstars. But it would need a compelling concept album title like Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars, or The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway. Bernie came up trumps again: Captain Fantastic And The Brown Dirt Cowboy. Both earthy and glam. Mysterious yet real. A musical origin story with Elton as the crazy Captain, and Bernie as the Cowboy with a conscience.

Given just four weeks to get it done even though it wouldn’t be released for another nine months, they set to work in a blizzard of cocaine. Meanwhile, Elton’s manager (and secret lover) John Reid made plans to launch what everyone agreed would be the most important album of the 27-year-old singer’s career.

Hubris, though, does its best work at such times. When Elton’s ’74 world tour ended with a show at London’s Hammersmith Odeon on Christmas Eve, for a live simulcast on BBC TV and radio, it was presented as a crowning achievement. For Elton, however, who was suffering from undiagnosed depression, paranoia and soul-deep loneliness, exacerbated by his excessive coke habit, it felt like an ending. And not a happy one.

A few weeks into 1975, without consulting anyone, he took the decision to fire his band. All gone in one fell swoop.

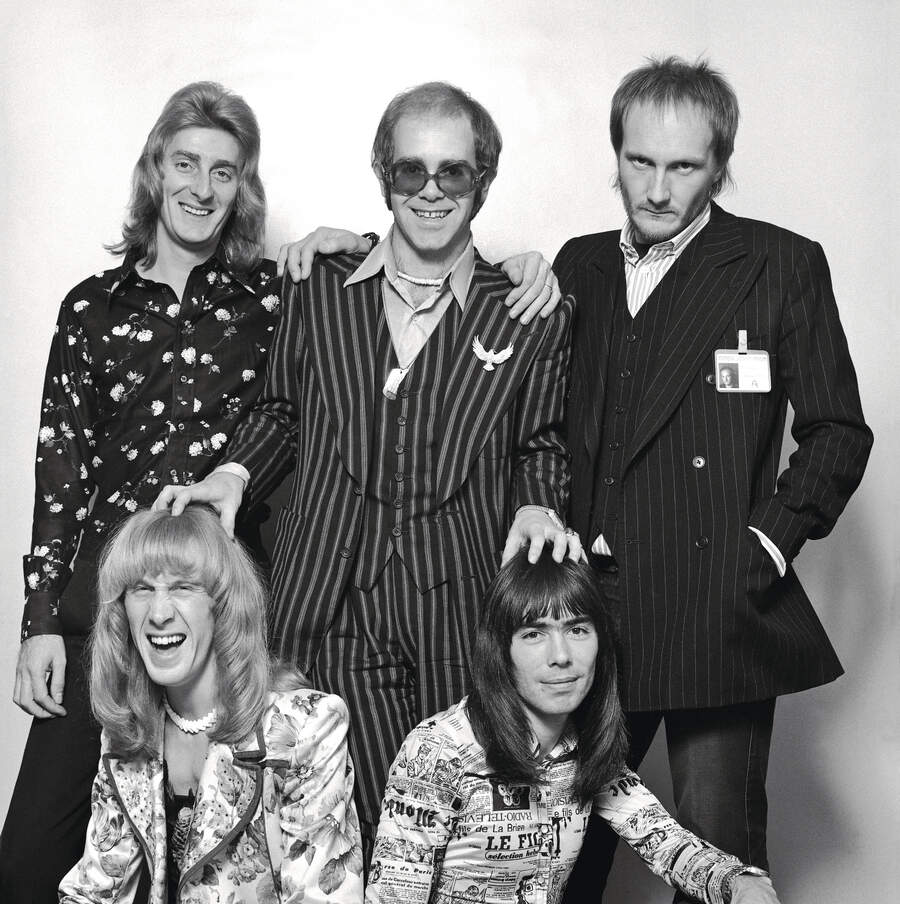

It seemed a bafflingly self-defeating move. Elton’s recent releases had been credited to “The Elton John Band”; many fans (and critics) thought it was about damn time. Built around longstanding mainstays guitarist Davey Johnstone, bassist Dee Murray and drummer Nigel Olsson, they had developed a distinctive sound across dozens of Elton hits. They were with him on TV, featured heavily on stage. For the big Thanksgiving Day show at the Garden, their names were spelled out in huge neon lights – Elton, Davey, Nigel, Dee and Ray (newcomer percussionist Ray Cooper). They had just recorded what was about to be pushed as the singer’s greatest album yet.

Dee Murray was scuba-diving in the West Indies when he got the call. “I could tell right off [Elton] was embarrassed about something,” he recalled. “He said: ‘I’ve decided to change the band. I think you, Nigel and I have gone as far as we can together.’” He told Murray he’d already called Olsen. Then both men called each other, confused, devastated, aghast. Only Davey Johnstone was spared – although he too would be gone in three years.

Recently it had become a thing, singers deciding they didn’t need the others. In 1975, Rod left the Faces, Bryan Ferry abandoned Roxy Music, Steve Harley sacked Cockney Rebel, and Ian Hunter fled Mott The Hoople. Maybe it gave Elton fresh ideas. Or maybe he’d been coked out of his mind one night and realised his whole life had been leading up to this point.

John Reid feared the rift might muddy the waters when they began rolling out promotion for the album. He needn’t have worried. Not in America, at least, where Captain Fantastic And The Brown Dirt Cowboy made history by going straight to No.1 in its first week of release – a landmark not even The Beatles or Elvis Presley ever achieved. It remained there for seven weeks, going gold in the US based on pre-release orders alone, then selling 1.4 million within four days of release.

In Britain (where it was released in May 1975) it was a different story. It was one of the few territories in the world where Captain Fantastic didn’t top the album chart, stalling at No.2. The solitary single from the album, the almost seven-minute-long Someone Saved My Life Tonight, despite huge fanfare, was a flop by Elton’s standards. Top five in America, it crawled to No.22 in the UK. Initially in thrall to the true-life romance aspect of the ‘young Elton and Bernie’ narrative, critics struggled with the remaining nine somewhat gothic, often corny, occasionally moving tracks.

Appearing in the order they were written, Bernie’s lyrics are heartfelt and plainspoken, devoid of his trademark cluttering of metaphors and images. These were “songs about trying to write songs,” declared Elton. “Songs about no one wanting our songs.” He added later that Captain Fantastic “was probably my finest album because it wasn’t commercial in any way”. It certainly wasn’t. Disappointingly dour and surprisingly devoid of hits, the album was – whisper it – actually rather dull.

That fact was belied by the kitchen-sink cover artwork, created by the psychedelic artist Alan Aldridge, of Beatles fame, and based on Hieronymus Bosch’s unnerving medieval triptych The Garden Of Earthly Delights. Elton appears in circus ringmaster drag, saddling his piano like a magic carpet, surrounded by fantastical figures capering through an elaborate collage of twisted grins and creepy, elongated fingers; two women, crocodile- and bird-headed, pose naked close to a strange ceramic jug figure that appears to be excreting sunflower seeds.

One can only guess that the carnivalesque artwork had been delivered long before the music, which begins with no fanfare at all with the title track. It appears at first a gentle popfolk song, Elton’s cod-American drawl reflecting on his ‘raised and regimented’ upbringing, while Bernie, the boy from the Lincolnshire wilds, ponders: ‘Shall I make my way out of my home in the woods?’ From there the track flowers elegantly into an irresistible groove. Tasteful but tainted. More thoughtful than curtain-raising.

Tower Of Babel, which follows, is equally restrained, at first, although its terse chorusing of ‘Sodom meet Gomorrah, Cain meet Abel’ and Johnstone’s layers of fiery guitars add intensity. The mood picks up with next track, Bitter Fingers, a musically jaunty but lyrically downbeat depiction of Elton’s early years playing pubs and clubs for pocket money. ‘It’s hard to write a song with bitter fingers,’ he chirps as the band kick into high gear.

Strings breeze through Tell Me When The Whistle Blows, bringing shimmer to this opaque tale of youthful uncertainty. ‘Long lost and lonely boy, you’re just a black sheep going home,’ Bernie writes, recalling his long train rides home to Lincolnshire after songwriting sessions in London with his unexpected new friend.

This leads into Someone Saved My Life Tonight. Specifically it’s about Elton’s former fiancée Linda Woodrow, who ‘almost had your hooks in me, didn’t you dear’. They had met in 1968. Elton was 21, a five-foot-seven virgin. Linda was 24 and four inches taller. He a struggling musician, she the heiress to a family fortune.

After Linda informed him she was pregnant, Elton, still a closeted homosexual, felt obliged to “do the right thing”, and proposed marriage. Linda accepted. Then days later she watched Bernie drag her fiancée out of the oven into which he’d placed his head, on a pillow, and turned on the gas.

“You know inside you’re making the wrong move,” Elton reflected later. “You deal with it by being preposterous.” So preposterous that the next day Elton and Linda ordered a wedding cake, and furniture for the marital home. The sorry saga came to an end only after openly gay singer Long John Baldry took Elton to task: “You don’t really love her! Don’t be a damned fool…” Elton burst into tears, and the wedding was off.

Side Two, as it quaintly used to be known, opens with the soft-rockin’ chugalug (Gotta Get A) Meal Ticket, another true-life story from the hard-scrabble life of two penniless songwriters dreaming the dream. Better Off Dead follows, hovering somewhere between Billy Joel and Gilbert O’Sullivan, with Bernie on strident form: ‘Through the grease-streaked window of an all-night cafe, we watched the arrested get taken away'."

What these days would be considered ‘a deep cut’, next comes the sickly sweet Writing. Making the rookie error of tethering the lyrics too literally to the narrative, it quickly descends into twee: ‘Oh I know you and you know me, it’s always half and half…’

The standout ballad is We All Fall In Love Sometimes, a musical conversation piece between lovers. Except again it’s Elton and Bernie staring into each other’s eyes. This far in, you wanna yell: “Okay, we get it! You had it tough in the beginning!”

You’re never allowed to lose focus on the fact that this is a concept album. Inevitably, then, the album closes with the suitably portentous Curtains, six minutes-plus of plodding everything-means-everything balladry; an all-hold-hands Wizard Of Oz dénouement.

While some critics found Captain Fantastic And The Brown Dirt Cowboy overindulgent and whimsical, Elton was unrepentant. He scolded Melody Maker: “I can’t understand the critics who say that Bernie and I must be egomaniacs. The album wasn’t meant to say: ‘Here we are, we’re wonderful!’” Adding: “I identify with this album so much more than anything else I’ve done. For me it will always be my favourite album.”

The feeling of hubris only mushroomed, however. With the much-loved Elton John Band gone, he had announced that his new band – EJB remnants Davey Johnstone and Ray Cooper, plus drummer Roger Pope, guitarist Caleb Quaye, bassist Kenny Passarelli, and on synthesiser James Newton Howard – would debut at Wembley Stadium on June 21, where the album would be live-premiered as a musical state occasion, and played in its entirety.

After top-notch support sets from Stackridge, Rufus with Chaka Khan, Joe Walsh, the Eagles and the Beach Boys – the last of whom delivered a full menu of crowd-slaying hits – Elton’s headlining set was met largely with restless indifference from the audience, caught off-guard by the prospect of Elton, the renowned showman, drunk and weary after a long day and night of grooving around and having fun, taking himself so seriously. It didn’t help that the album had only been on sale a few weeks and that most people didn’t know the songs yet.

“People started to leave. I was terrified,” Elton recalled. “It was years since I’d lost an audience. I couldn’t just suddenly strike up with Crocodile Rock halfway through. We eventually got round to the hits, but it was too little too late, as the reviews quite rightly pointed out.”

Elton dealt with this latest calamity the only way he knew how: by plunging straight back into the studio – Caribou, again – to record a new album, titled Rock Of The Westies, which was released just four months later. It was his last album to reach No.1 in the US, while in the UK it barely scraped the top five. Elton John’s imperial period was over, the captain going down with the ship, announcing his retirement two years later. The first, but of course not the last…