Being true to yourself is not easy in the music business. Most of the reality TV stars, singer-songwriters and half-baked indie bands that clog up the charts have to toe a company line, dress this way, look cool at all costs, create a new genre or rip off that sound everyone is buying into now, smile for the camera, supply that next hit single…

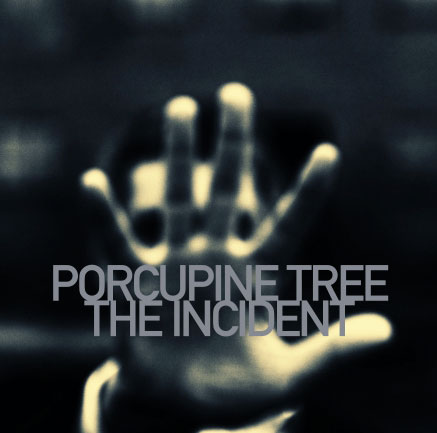

It’s always been that way, but there have always been outsiders, mavericks, who refuse to operate that way. Steven Wilson and his band, Porcupine Tree, do not operate that way. He has remained fiercely independent throughout his career, right up to Porcupine Tree’s highly conceptual 10th album, The Incident. Like his other bands such as No-Man, and his recent solo album Insurgentes, his work is progressive in the best sense of the word. It’s creative, diverse, forward-thinking music that doesn’t care whatsoever about hit singles, chart placings or gold discs – despite the fact that his band has been a slow-burning success for the best part of two decades.

The key word for Wilson is “album”. This is not a man who is a big fan of leaks or downloads. But there is an upside that, when we meet, brings a smile to his face – and should do to yours. “That the download culture is becoming more dominant doesn’t have to be a bad thing,” he says. “We had, for example, Mike Skinner with The Streets. A Grand Don’t Come For Free was a concept album by a British hip-hop artist. It helped liberate this idea of music as a three-minute pop song. If radio and MTV have no influence anymore, the idea of the single becomes less relevant, and people start thinking about albums again, so you have bands like Radiohead, Tool, The Mars Volta, Mastodon more recently, even Coldplay… big bands are thinking about the album as a statement.”

Wilson was a prodigious talent from an early age, working in his bedroom, teaching himself guitar and keyboards, making tape after tape of sounds, riffs and songs. Ironically, Porcupine Tree began as a joke – a made-up band with a false history, an imaginary 70s prog outfit with a full discography and band biogs. But then Wilson began releasing largely ambient and psychedelic music under the name, and eventually, when he began to attract interest from the music industry, he needed a band to tour with.

Enter some real-life musicians! Keyboardist Richard Barbieri had been in early 80s art-rock band Japan, while Colin Edwin joined on bass at the same time as Barbieri in 1993, and Gavin Harrison replaced original drummer Chris Maitland in 2002. But this is far from a backing band.

“The solo album is me, with no consideration for collaborators at all,” says Wilson. “That’s the kind of music that left to my own devices I make for myself, and is a bit more eclectic. But Porcupine Tree has a sound and that comes from the four musicians, so although people may see the credits and think, ‘Oh, Steven Wilson writes everything and the musicians are just doing what he’s written,’ that’s not the case. I’d never ask them to play something I didn’t think they’d enjoy. I know that the sound has to be something we all agree on. Imagine the four personalities as a Venn diagram – where those four personalities cross is the sound of Porcupine Tree, so I write in that area.”

That doesn’t mean it’s easy. “If you’ve written a song it’s your baby and you’re precious about it. Sometimes they suggest changes that aren’t what I had in mind, but I want to know what they think. Gavin comes up with very different drum parts than I would ever have thought of, and Richard is all about sound design, and a lot of the time what you’re listening to is the detail, the subtlety he’s put in there. The sound design aspect, for me, makes the records, and that’s all him. It’s very much a band, which is sometimes a frustration – that’s why I do solo projects as well because they can’t always fit my own way, but that’s good. That’s what being in a band is all about. The compromise gives you that sound.”

Porcupine Tree have always been experimental, but have developed, progressed and become heavier over time. A sea change occurred in the early part of this decade when Wilson produced Swedish prog-metallers Opeth, who had toured with Porcupine Tree and struck a chord, so to speak, by ploughing their own furrow. But Wilson is quick to dispel the myth that 2003’s In Absentia was influenced by the fact that he had been invited to produce Opeth’s Blackwater Park album.

“It was the opposite,” Wilson says. “The reason I worked with Opeth is that I was already becoming more interested in heavy music again, not the other way round. In Absentia was written before I worked with Opeth so I’d already moved towards that. The first music I ever really liked as a kid was the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal. This was the first music that was really mine, in my time – bands like Diamond Head and Saxon – so that was in my DNA. Like a lot of people as they get older, I moved away from metal. I had this thing in the back of my mind that metal was something I’d grown out of, in a patronising kind of way.”

There’s a very good reason for that. “Most of the metal I was hearing was Korn and nu-metal stuff, but then I got turned on to bands like Sugar and Opeth and I was blown away, because I suddenly realised where all this incredible creativity that had been missing from mainstream metal – and even progressive music at that time. It was sophisticated, album-based music. That revitalised my interest. With In Absentia and producing Opeth, it all came together at the same time.”

Porcupine Tree’s new album, The Incident, harks back to an earlier age of prog, featuring a series of songs sequenced in Roman numerals, rather than in standard numbers for the iPod generation, which flow from one to another in a seamless way. In fact it moves the genre forward – it transcends any genre, but the influences are wide-ranging, far-reaching…

“Wilson is a genius, I think.” So said Derek Taylor, the dapper, very English PR guru who helped make The Beatles huge before being poached by The Beach Boys in the mid-60s to turn the surfer boys onto a more alternative crowd. He was talking about Steven’s namesake Brian – the Beach Boy who had a meltdown and abandoned his magnum opus Smile in 1967 before finally completing it in 2004, but it could just as easily apply to the Porcupine Tree mainman. And the reason for bringing this up is to highlight the sheer breadth of Steven’s influences.

“What I love about Smile is that you have a series of songs that have reccurring themes, melodies and chord sequences,” says Steven. “The Beach Boys were a huge influence on my vocals. I finally discovered a way that I could feel confident about being a singer. I’d never thought of myself as a singer or had the confidence to push myself forward, but listening to Brian Wilson’s great works gave me the confidence to start using harmony vocals, but in a rock context. It was around the time of In Absentia, when we started to reach a bigger audience – there was something fresh about the fusion of harmony vocals with heavy riffs.”

Wilson’s influences are diverse, and in come cases surprising, which may explain why Porcupine Tree sound like no-one else in the modern sphere of music. “When I grew up my father was into stuff like Dark Side Of The Moon and my mother was listening to Donna Summer, John Coltrane and Marvin Gaye records, which were also conceptual in the way they were structured. So for me they became the two sides to my musical personality, but the thing they both had in common was the idea of the album as musical continuum, a musical journey. And then as I grew up I discovered other things, like Marillion and Jethro Tull. I loved anything that had this ambition to elevate the album above just 10 songs strung together. You see that influence in all of our work, but The Incident takes it to the next level, not just as an album that’s sequenced well but as an album that’s a complete listening experience.”

The album as a concept is where we arrive back to, but in a way Wilson too has come full circle. From early ambient works such as Voyage 34, a 30-minute single that combined guitars with the technological influence of similarly independent early 90s electronic pioneers such as Future Sound Of London and The Orb, Porcupine Tree moved in a more song-oriented direction from 1999’s Stupid Dream album, grew heavier, and have landed at The Incident, 70-plus minutes of vignettes that can be taken individually but which also form a cohesive whole.

In the same way, Wilson is a bag of contradictions when it comes to technology – although not a fan of downloads he says, “I wouldn’t rule out a download release in the future. But because of the era I grew up in I’m very romantic about the physical format, particularly when it’s done well. A lot of CD releases are functional and not very exciting or inspiring, but I think when it’s done properly, you can make things that people still really want to own, and cherish, that are magical and beautiful, in the same way you’d want to own a beautiful painting.”

Aside from the physical aspect, Porcupine Tree have pioneered albums in 5.1 surround sound, so as well as touring this autumn Wilson is working with Robert Fripp to convert some of King Crimson’s back catalogue. “It’s a dream come true. It’s a real bonus that because I’m a specialist in 5.1 I have the opportunity to approach the likes of Robert, and other people from that era. I’ve asked Alex [Lifeson, who guested on the Fear Of A Blank Planet album] if I can do the Rush stuff, which would be amazing.”

Sound, ambition, feel. Those are the things that you sense drive Steven Wilson, no matter what he’s writing, producing or mixing. Porcupine Tree have built up a huge following across the world, won awards, been up for a Grammy… none of that, you sense, really matters to Wilson. His band have helped revived interest in progressive music, and that maybe matters to him more. Enjoy The Incident, but already we have to wonder where he will go next…

This article originally appeared in issue 10 of Prog Magazine.