There is a small chance that by the time you’re reading this, Perry Farrell will have lost his voice. The former frontman of Jane’s Addiction, Porno For Pyros and Satellite Party, the founder of Lollapalooza – the festival that became the template for Coachella and a host of other bohemian-minded, open-air behemoths – and an artist whose drug intake was legendary even for the LA scene he emerged from, is only now, at the age of 61, starting to feel the effect of a lifetime’s worth of revolutionising, rock’n’roll hedonism.

“I’m set to get three vertebrae in my neck replaced next week,” says the singer, sounding remarkably unconcerned, from his home in the coastal idyll of the Santa Monica Canyon. “I feel fine, it’s just that I’ve had a pain in the neck for the past three years from years of singing and headbanging. They’re going to go in there and do microsurgery. It sounds amazing and scary and yes, there is this very small chance that I would lose my voice, because it’s in an area near the vocal box, but I just want to get it behind me. I’m expecting, within four weeks, to start singing again.”

Perry Farrell isn’t one to dwell on downsides, or for that matter, much else other than the immeasurable vistas of possibility he still sees ahead of him. Considering he has a nine-disc, largely retrospective box set out called The Glitz; The Glamour! that takes in his pre-Jane’s goth band Psi Com, Satellite Party’s Ultra Payloaded and his two solo albums – 2001’s Song Yet To Be Sung and last year’s Kind Heaven – alongside a host of rarities and remixes, Perry’s ever-curious brain is only tangentially occupied with taking stock, reliving the past or considering the huge legacy he’s engendered. Charming, engagingly idealistic and fuelled by a mercurial urgency that doesn’t entirely belong to this dimension, he has a habit of taking the scenic route from any question you might put to him, but one where wisdom, innocence and wonder are constant features of the landscape.

“I tend to love to look forward, and then sometimes forget that I’m missing a shoe, so to speak,” he says when asked how the box set came about. “But my management team have really done a stellar job of reaching out and finding where all my music was located. When they asked me where the Satellite Party record was, I said, ‘I bought it back off the record company [Columbia]!’ They said, ‘Well, let’s put it out.’ I mean, you can’t find it on the typical routes of distribution – Spotify didn’t have it. And I have to admit this… I wouldn’t say I’m an airhead on purpose, or that I purposely choose to ignore things, but there’s a certain side of me that enjoys burying treasure. It becomes that much more valuable when you discover it. It’s kind of like looking for Atlantis.”

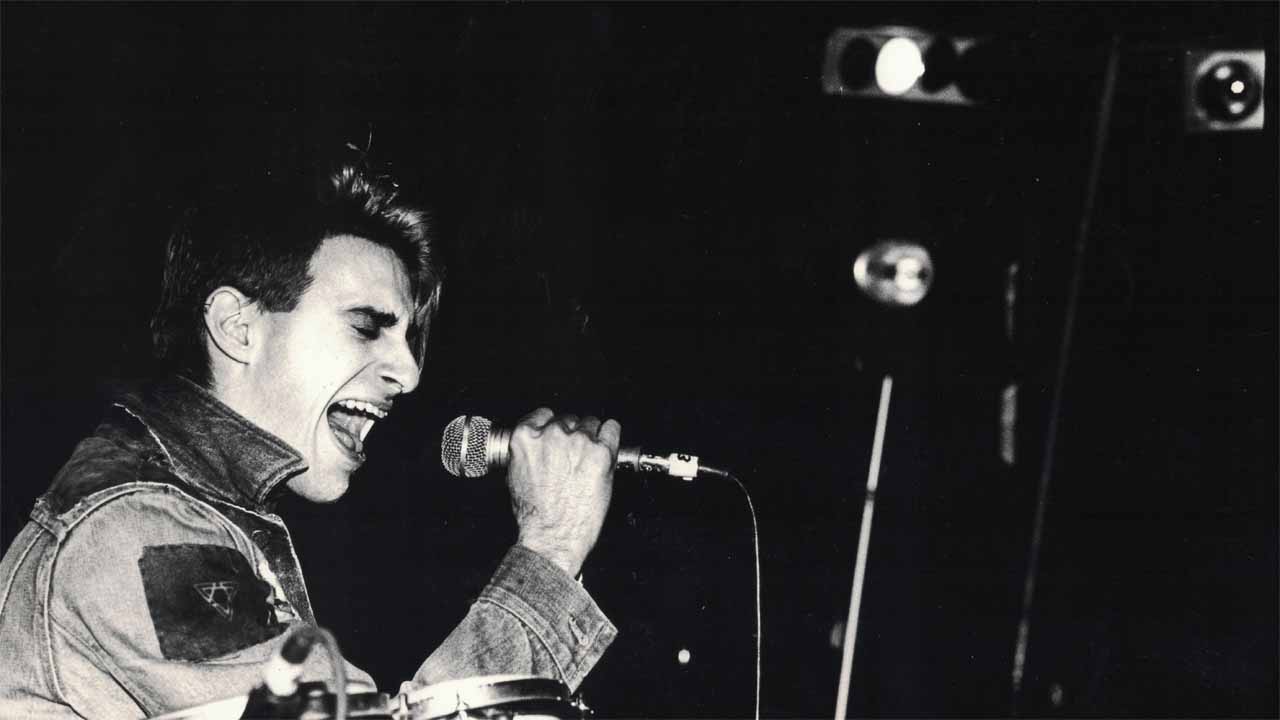

For many, the biggest discovery on The Glitz; The Glamour will be the ultra-rare five-track EP from Perry’s first band, Psi Com. Formed in 1981 and steeped in the kind of Bauhaus and The Cult-infused post-punk and goth that’s seeing a scene-wide revival now, it was a sound hardly native to the sun-drenched West Coast – even if The Cult ended up gravitating there in return. But for all its stark, angular dispatches from the shadows, you can hear the genesis of something irrepressibly inquisitive – a tentative roadmap for what was to come. How much of himself does he recognise in those early recordings?

“You know, I hadn’t listened to those tapes since, because my head is always in the moment,” admits Perry. “But I saw that I was a young man who was trying very hard to aspire towards greatness. I was giving it a real effort. I wanted to be the type of person that Jim Morrison was, or Ian Curtis was. Jim Morrison could be outrageous, and I have my own personality, so I’m not going to be exactly like either of those, but what those men shot for was greatness, and at least I made the attempt.”

For Perry, aspiring to that kind of greatness wasn’t an end in itself. As with his heroes, it wasn’t the fulfilment of blind ambition, but of a worldview, however embryonic it might have then been – a hunger to force the world to account for you, to effect change.

“If you’re shooting for greatness like ‘Make America Great’, that’s bullshit. If you’re saying, ‘Let’s make the world great, let’s make ourselves great’, then that’s brotherhood, that’s a great spirit. There was a movement around that time, but we were mixing quite well with everybody. So, for example, you would see at our shows rockabillies, punks, S&M bondage people, gays, fashionistas. And then there were kids who were coming from the valley who liked rock and hard rock and Van Halen.

“So it was a great time,” Perry continues, “because we were creating, and culture was happening. It’s a wonderful time when nobody really knows anything, and so you were free to do what thou wilt. I had the luxury of being free, because I had no money, and I didn’t have many obligations. So that gave me the most freedom that I ever had in those days to be creative and to try things, and the things that didn’t quite work, you discard. It’s kind of like car design – you don’t make new car designs because your car is broke, right? You make your new car design because you are trying to evolve the concept of an automobile.”

Although not included in the box set, Jane’s Addiction remain the nucleus around which Perry Farrell’s career has spun. Their debut, self-titled live album in 1987, and the two studio albums that followed, 1988’s Nothing Shocking and 1990’s landmark Ritual De Lo Habitual, might have had their roots in the Sunset Strip sound – you can see the members at a street party, alongside members of Guns N’ Roses, on Penelope Spheeris’s 1988 documentary, The Decline Of Western Civilization Part II: The Metal Years – but they were a glorious, liberating mutation, too. Some of that was down to Dave Navarro’s soaring, expansive leads – as one writer put it, “Jane’s Addiction rock out in 360°” – but the freak flag they flew was hoisted by Perry.

Androgynous, dreadlocked and flamboyant, with a face that bordered on the cubist, the frontman didn’t offer a haven for fellow misfits; he offered a Technicolor celebration of difference, and allowance for it to run free. As he sung on Ain’t No Right from Ritual…, before its exhilarating, jet-fuelled guitar ‘whoosh!’, ‘I am skin and bones, I am pointy nose / But it motherfuckin’ makes me try!’.

“You have to have a message that is helpful and healing and all those other things,” says Perry. “The stories on those albums were very personal, but anyone can do it. You really have to come to know yourself, and get in your head to the point where you can place your voice anywhere and assess the world, and project it back through art. It’s just a practice.”

Jane’s’ introduction of firecracker funk and dub amongst a host of spectacular, speculative detours wasn’t mere eclecticism; it was a map of a mind that couldn’t stay still. It was impossible to replicate, but in its breaking down of barriers and smashing of masculine norms, its influence on the grunge scene – and their own rejection of metal’s mid/late 80s slide into posturing and conservatism – was immense. They were regularly cited by the likes of Rage Against The Machine, Tool and Soundgarden as the ground zero for alternative rock.

“I think we gained our freedom by doing excellent work, and that gave us our right to experiment,” says Perry. “Our label trusted us, and we were fortunate. People were always saying something is dying, like, ‘Rock’n’roll is dying.’ They weren’t seeing something growing. What I’m trying to tell you is, man, in this dystopian world, start looking for that utopian world.”

That urge to remake the world in a utopian light has only become more pronounced since, from the creation of Lollapalooza, to his freeing of 2,300 Sudanese slaves in 2001 with money generated by a Jane’s Addiction reunion, to his creation of a multimedia art and entertainment space in LA linked to his Kind Heaven album. That Perry Farrell has chosen to be defined by this outlook, rather than the traumas he’s experienced, not least his mother’s death by suicide when he was three, is testament to a man who’s bound to the transformative nature of art.

“What’s the point of dwelling on something that’s terrible all the time?” he asks. “I’ll tell you what my last four years have been. It started with my wife miscarrying, on election night. Now I can be as sad as the next guy about what’s happened to my family and me, but most people have the same amount of tragedy. Everybody loses people that they love, so there we all share a common experience. If you lose them you never forget them. There is a certain compartment in my mind where it’s still there. I don’t discard it, it becomes part of a family album that you make beautiful, and that is what I choose to do.”