Peter Baumann’s audition for Tangerine Dream was, by any standards, a little unorthodox. Invited over as a possible replacement for outgoing organist Steve Schroyder, the 18-year-old was faced with one tiny problem: he couldn’t actually play keyboards. Band members Edgar Froese and Christopher Franke pressed on regardless. Within 20 minutes, Baumann was offered the job.

“I knew the difference between white and black keys, but that was about it,” he recalls of that day in 1971. “I got together with them and Edgar said: ‘Just start playing.’ That was it. It was a very extreme exploration of sound and its modifications. At the time, Edgar was also using the guitar in very unconventional ways. I had a reverberation spring attached to my Farfisa organ, which I started to rattle, and it made an enormous, thunderous noise. It was an aggressive sound that really disrupted things, a counterpoint to some kind of smooth, tonal landscape. After the session, Edgar went: ‘Yeah, that was very cool. Let’s go and play a concert.’ When it came time to get on stage, the lights dimmed and we just started to make sounds. It was very adventurous.”

Baumann was a perfect fit for Tangerine Dream. Led by Froese, who had founded the band as a fluid collective in 1967, they had left behind their early experiments with tape collage and rock guitar and were busy exploring largely uncharted ground. Their latest album, Alpha Centauri, had mixed up organ and flute with electronic textures. The addition of Baumann coincided with a deeper exploration of the latter, an enterprise in atmospheric sound that Froese liked to call ‘kosmische musik’. These synthetic spacescapes found their first expression in the abstract moods of 1972’s Zeit, which marked Baumann’s debut with the band.

Music critics didn’t know what to make of it. “There was no statement saying that synths would be a passing fad,” Froese said in 2010. “Critics had no words to describe their dislike of the equipment we were using, because they hadn’t seen it before. If you look at the development of the arts through the centuries, it’s always been the same intense reaction: conservative opinions against the fresh breeze of changing crystallized structures. It’s like the old saying: ‘What a dog doesn’t know well, he won’t eat.’”

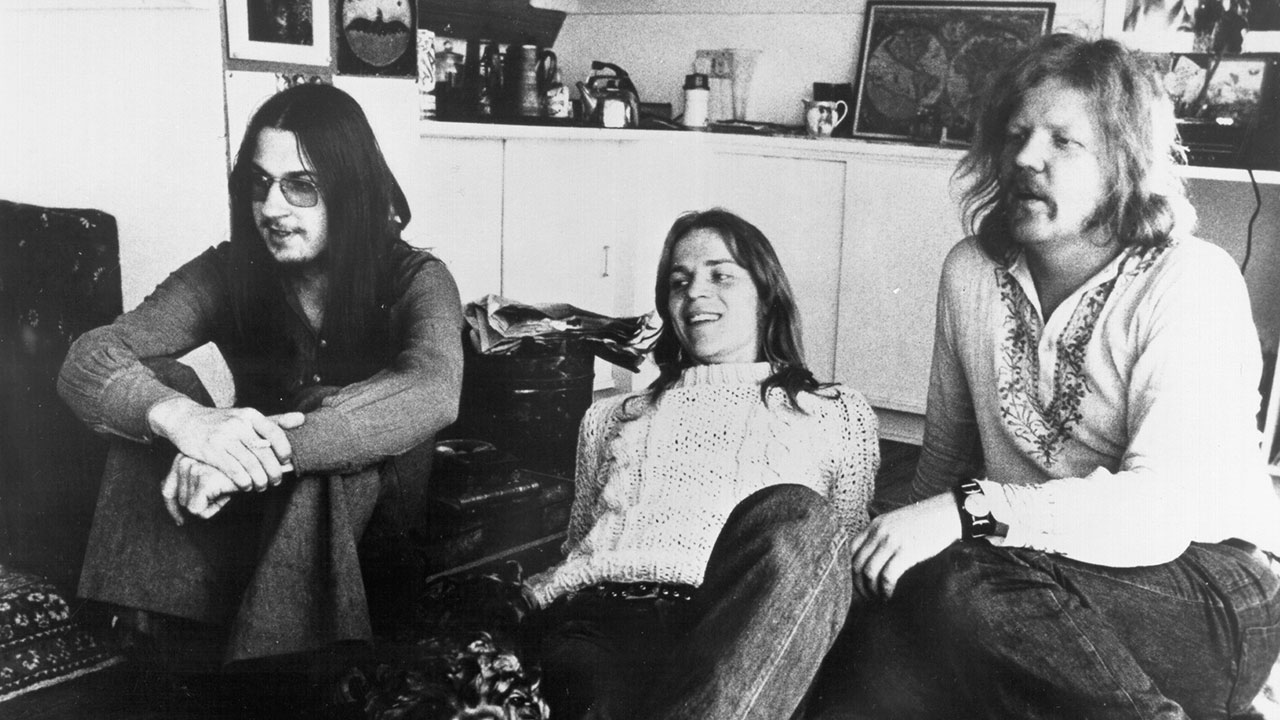

The core trio of Baumann, Froese and Franke stayed together until 1977, a crucial period that saw Tangerine Dream emerge as the forefathers of progressive synthtronica via a series of defining albums: Atem, Phaedra, Rubycon, Stratosfear and the soundtrack for William Friedkin’s Sorcerer, a body of work that prized innovation over pure technique.

“It was really about the intuitive feel for what sat together,” Baumann explains. “Deciding which directions the music should take involves very intuitive things and, ultimately, accidents. So if you have three individuals who are adventurous and experimenting, then the accidents just multiply. We were always on the lookout for anything that made noise. I was crushing glasses against the wall and recording that before the synthesiser came along. It was all about what sounds would raise our interest. When you get certain individuals together in one room, it comes down to chemistry. Somehow it just worked in this particular constellation. In Tangerine Dream, I never felt as though it was ever about any one individual. Music was the main focus. So the music and atmosphere that it created became the fourth entity. You could feel that it was beyond yourself.”

Baumann also believes that the nature of Tangerine Dream’s music lent itself more to prog than it did the reductive, and often disparaging, term Krautrock. “We felt that we were at the far end of progressive music,” he states. “There were some classical electronic composers and a few others that did experimental music, but the Krautrock artists – like Kraftwerk, for instance – had fully composed everything. Every note was completely designed and in its proper place. But that was progressive for the time as well.”

One of Tangerine Dream’s chief inceptions was the use of electronic sequencers, beginning with 1974’s Phaedra. This gave their instrumental sound added richness and scope, allowing for a wider spread of layered impressions and futuristic pulses.

“It goes back to my early years as a pupil of classical music,” Froese noted, “when I realised that everything in musical structure is bass-oriented. Specifically Bach’s compositions, where he explained it perfectly in his fugues and toccatas. Tangerine Dream were the first band to ever use the Moog modular system – introduced by Bob Moog and Wendy Carlos – as a standalone sequencer, as proved by listening to the title track of Phaedra. The programming of these sequencers was time-consuming, but it gave you the endless freedom to improvise on top of the basslines.”

Phaedra also signalled the onset of Tangerine Dream as a commercial proposition, at least in the UK. Boosted by the demand for imports of Atem, their previous LP, the band signed to Richard Branson’s Virgin label. Phaedra duly notched up six-figure sales figures and cracked the Top 20, mostly through word of mouth.

- Tangerine Dream share Stranger Things covers

- Tangerine Dream’s Edgar Froese dead at 70

- Tangerine Dream's Out Of This World gets vinyl release

- Tangerine Dream movie nears crowdfunding deadline

There was also a sharp increase in attendance at live shows, where Tangerine Dream had always tended to polarise opinion. “After many of our early performances, the stage would often look like a weekly vegetable market rather than a concert stage,” recalled Froese. “People had some fun throwing bad apples and bananas towards our electronic gear and were laughing their asses off. You need a lot of trust in your beliefs, and even more patience, that one day it will be over. We didn’t have a great open-minded crowd in those days. There was a rejection attitude all the way through, right up until we released Phaedra. That album did help to build a career I never dreamed of in my early years.”

Baumann remembers that “the overall atmosphere was always unique whenever we had a concert, simply because there was no showmanship involved. There was nobody dancing on stage, there were no vocals and no real ‘performance’. And we often had our backs to the audience. It was truly about just the music. Some nights were more intense than others, but it was always unique. You could feel whether the audience was attentive and really with the music, or whether they were leaning back and waiting for something to happen. When there are a couple of thousand people all focused and following every note, then there is a real potency there.

“We’d play to mostly college kids and the younger crowd. They all had long hair and smoked a lot of pot. After Phaedra the concerts got much bigger and we toured a lot more. The instruments and the sound became more sophisticated and we started using quadrophonic sound.”

Perhaps the most famous, or infamous, Tangerine Dream gig came at the back end of 1974, when they shared a bill with Nico at Reims Cathedral, north-east of Paris. Looking somewhat incongruous amid the gothic splendour, stood behind a nest of wires and banks of equipment, the trio delivered a meditative, trance-like set. The authorities had estimated a crowd of between 1,500-3,000, which turned out to be a gross miscalculation.

“We were in this cathedral that was hundreds of years old and there were 6,000 people there,” says Baumann. “It was very dark – there were a couple of lightbulbs just below the ceiling and a lot of people were smoking pot, so there was this kind of fog in the air. It was a very eerie and intense atmosphere. The acoustics in a cathedral are obviously quite different from those of a concert hall, so we adjusted to that intuitively and played much more sparsely. We basically just sent sounds out into this huge echo chamber.”

The show was a huge success, though local church groups were less inclined to agree. Having neglected to provide refreshments or even basic toilets, the organisers were left to clean up an almighty human tip afterwards. As Froese later lamented to Melody Maker: “It was a terrible situation. People couldn’t move, they had to piss up against the walls. You can imagine the mess by the end of the concert. What’s more, we got the blame for it!”

It was a story that continued to run for weeks, with pages of media coverage devoted to the notion of rock groups being invited into a place of holy worship, not to mention the flagrant use of marijuana. One Catholic group went so far as to demand retribution for “those irresponsible souls that desecrated this historic and venerable site”.

Other shows were less problematic. Tangerine Dream’s reputation rested on their love of improvisation and a symbiotic relationship with the venues they played in. Their late-70s gigs concerts tended to be minimal, low-key affairs. One gig, for example, at York Minster in October 1975, was conducted in complete darkness.

Baumann’s tenure with the band came to an end after a fallout with Froese: “It just felt like it wasn’t as much fun any more. And I think Edgar wanted to go in some other direction.” He made a handful of solo albums before setting up Private Music in 1985. This label served as a repository for various new age and electro-centric artists, among them Suzanne Ciani, Yanni, Patrick O’Hearn and, eventually, a new iteration of Tangerine Dream.

By the millennium, he’d left music to concentrate on philosophy, science and evolutionary theory, an interest that led to him setting up the Baumann Foundation in 2009. It was only in 2014 that he rediscovered the urge to create music again. He built a studio in his California basement and began assembling a few song ideas. This in turn led to him reconnecting with Froese. The pair met up in Austria in early January 2015, a meeting Baumann calls “an extraordinary encounter”, during which they talked about working together again. Alas, Froese passed away just weeks later.

Baumann has remained committed to the cause, however. Earlier this year he released Machines Of Desire, his first new album in decades. “It really was a joyful re-entry into music,” he says, adding that his time in Tangerine Dream was a subconscious reference point. “I always had a particular flavour within the group and was more interested in extreme spatial ideas and broad spectrums – real deep bass and clear highs, and lots of reverb and delays. It was always leaning towards making the music sound very three-dimensional, so that was a big part of the Machines… album. The wonderful thing about doing instrumental music is that you don’t have any thought processes. It’s all intuitive, it’s all creative.”

He’s already planning a follow-up and reveals that he’s also been in touch with Froese’s widow, Bianca. “We speak once in a while and there’s a new documentary about the band, which I’ve done some interviews for [Tangerine Dream: Sounds From Another World, directed by Margarete Kreuzer]. We have a wonderful relationship. Who knows, maybe we’ll do something together, or not, in the future. It was always a matter of chemistry. And the original line-up of Edgar, Christopher and myself was so unique that it’s hard to find something that fits that well. I wouldn’t want to be part of something just for the sake of it.”

As for those glory years in Tangerine Dream, does he ever get the chance to appreciate just how important the band were? “Not at all. Looking back, you think it was pretty cool. But at the time there wasn’t much to compare it to. As I say, we just did it out of intuition and enjoyed doing what we did. We had no idea that it was all that influential.”