Hailed as a genius by everyone from Eric Clapton to Noel Gallagher, late Fleetwood Mac founder Peter Green was one of the greatest British blues guitarists of his generation. In 2012, eight years before his death at the age of 73, Classic Rock was granted a rare audience with a reclusive man who changed music without ever truly conquering his demons.

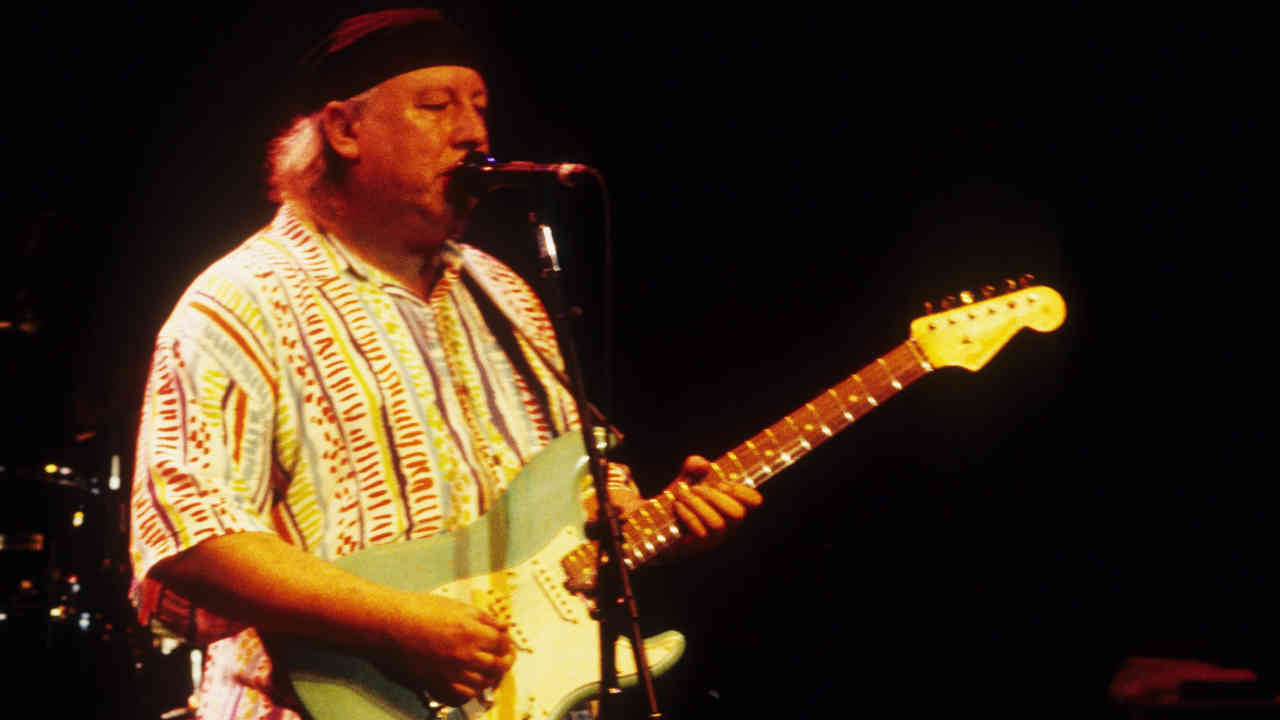

Peter Green sits in his lawyer’s office overlooking one of London’s most popular shopping thoroughfares. As you climb the stairs, you can hear the guitarist’s sing-song East End accent drifting down from above. Later, Green will compare his appearance in the 1960s to that of a “riverboat captain”. In fact, the description better suits his 65-year-old self. Today, he wears a yellow polo shirt, is clean-shaven, and has the remains of his white hair cut short, but he’d still look at home behind the wheel of a tugboat puttering up the Thames.

Then again, incongruity is all part of the Peter Green story. His work with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and Fleetwood Mac has inspired musicians as diverse as Carlos Santana, Gary Moore and Noel Gallagher. Then, just as rock music was becoming big business, Green turned his back on it all, tortured by guilt over the money he was making and with his thought processes damaged by hallucinogenic drugs.

Too often, though, the mythology surrounding Peter Green crowds out his musical achievements. During a creative burst that lasted a little over five years, Green became the guitar hero’s guitar hero. An instinctive musician with a powerful but unadorned style of playing, he eschewed the flash and braggadocio of his peers while earning their respect and admiration. Even in the decade of Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton and Jimmy Page, Green carved out his own niche. Tracks such as the timeless Oh Well, Man Of The World and Need Your Love So Bad established him as a singular songwriter, a blues purist who ended up creating his own style of blues. Peter Green is a unique but these days often overlooked talent.

When he cracks a smile, you briefly glimpse the pop star he once was. While he’s anything but the hopeless acid casualty of rock legend, Green broadcasts on his own wavelength. During our hour together he’s funny, fascinating, confused, confusing, sometimes frustratingly self-deprecating but, most importantly, lucid – not least when talking about his music and where it came from. “The thing about the blues,” he says, “was making it mean something to me personally.”

Peter Green was born Peter Allen Greenbaum on October 29, 1946, the youngest of four, into a Jewish family in Mile End, East London. Ten years earlier, Oswald Mosley and his British Union Of Fascists had clashed with the local Jewish community while trying to march through their neighbourhood. Two years after Peter’s birth, his father changed the family name by deed poll to Green and moved them west to Putney.

For many years, Green hinted at a childhood troubled by anti-Semitism. “I was always a sad person,” he claimed in 1978. “I felt a deep sadness with my heritage.” Elder brother Michael, talking to Green’s biographer Martin Celmins, recalled: “A couple of times local kids would throw stones at the window and shout, ‘Yid.’” He admitted that it may have left an impression on Peter, who he described as a sensitive child who “questioned everything”.

Green first picked up a guitar at the age of 10, after watching Michael and his other brother Lenny playing, but claims he “didn’t take it seriously” until he reached his teens. By then he’d developed a good ear for music and could mimic singers he heard on the radio. His playing was now far ahead of both siblings. “Peter was a natural,” said Michael. “I’d be thinking: ‘God, I’ll never be able to do what he’s doing there.’”

Hearing a friend’s 78rpm record of Muddy Waters’s Honey Bee turned Green on to the blues, a musical obsession that would never leave him. After quitting school, he took jobs as a butcher’s boy and apprentice French polisher, while playing bass in a West London dance band called the Ken Cats and, later, with Eel Pie Island regulars The Muskrats. When he wasn’t playing gigs himself, Green could be found back at the Crawdaddy club in Richmond or the dilapidated Eel Pie Island Hotel, watching the likes of The Yardbirds and assessing the competition. It was while playing with The Muskrats that his musical ambition became apparent. Just as with his brothers, his playing ability was ahead of his bandmates. It quickly became apparent that he wouldn’t stick with the amateur group forever.

In August 1965, Green felt confident enough to hustle his way into a gig with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, a boot camp/finishing school for some of the UK’s finest blues musicians. Bluesbreakers guitarist Eric Clapton had taken temporary leave and gone to Greece. Such was his reputation that the words ‘Clapton Is God’ had been spray‑painted on a wall in North London. Mayall appointed a replacement, Jeff Kribbett, but Green caught a show at London’s Marquee and was unimpressed.

“He kept coming down to all the gigs and saying: ‘I’m much better than him,’” recalled Mayall. In the end, he let “the Cockney kid” take over. But the pushy 19-year-old who talked his way into one of London’s hottest groups is utterly at odds with the self-deprecating 65-year-old of today.

“John Mayall paid me a great compliment. He said I was the best guitarist he’d heard since Eric Clapton,” says Green. “I tried to float on that. But I used to drink before I went on. It seemed to be the thing where everyone went to the pub. I couldn’t play properly. Most of them [gigs] I flunked.”

If Mayall was disappointed, he never said so. When Clapton returned, he was impressed by his understudy. “He was a real Turk,” the guitarist later said of Green. “A strong, confident person who knew exactly where he was going.” But after just three gigs, Clapton resumed his place in the band, to Green’s profound disappointment.

Undeterred, in February the following year, Green auditioned for Peter B’s Looners. Peter B was Peter Bardens, a keyboard player who would later find success in Camel. Their drummer was a gangling, six-foot-five loose cannon named Mick Fleetwood. “They had funny clothes on,” Green says now. “Hipsters with big belts and fancy buckles. It might have been Carnaby Street stuff, but it blew my mind.” Green landed the job, but with his denim jeans and “river boat captain” sideburns, he’d yet to embrace the boutique fashions of the era. “Peter Bardens would say to me: ‘You look like a dustman,’” he grins. For Green, it really was all about the music.

He made his recording debut with Peter B later that year, on the Booker T-inspired single If You Want To Be Happy. In July, when Clapton quit the Bluesbreakers to start Cream, John Mayall knew whom to call.

Mayall’s landmark album Blues Breakers With Eric Clapton had only just come out. By October 1966, Mayall and his group were back in Decca Studios in West Hampstead – but minus their godlike lead guitarist. “As the band walked in the studio, I noticed an amplifier which I never saw before,” recalled producer Mike Vernon. “So I said to John Mayall: ‘Where’s Eric Clapton?’ Mayall answered: ‘He’s not with us any more. He left us a few weeks ago… Don’t worry, we got someone better.’” Vernon was incredulous. But Mayall was adamant that “in a couple of years he’s [Peter Green] going to be the best”.

The Bluesbreakers’ next album, A Hard Road, featured two Green compositions, including an instrumental, The Supernatural, on which he sketched out a sinuous, improvised style of playing, later revisited on Fleetwood Mac’s Black Magic Woman.On the road, though, Green faced sceptical audiences.

“I don’t know anyone who wouldn’t be worried about having to follow Eric,” he says now. There were hecklers. But within a fortnight, Green had won them over. While Clapton would soon be finessing a high-speed style of playing with Cream, Green favoured slow, measured solos. “Peter had a deftness, a more melodic style… deeper blues,” said Mike Vernon.

Green has mixed feelings about his playing from that time: “Sometimes I’d feel confident. Other times I feel like I’m going too fast.” He also noticed that the faster he played, the more favourably some of the audience responded. The era of the guitar hero had arrived. But Green condemned the craze for what he called “7,541 notes a minute”. He wanted no part of it. “I don’t like people to say to me: ‘Oh, you’re better than Eric Clapton,’ all this kind of thing. People used to do that, and I didn’t know where to put myself.”

Green had another fortuitous encounter while in the Bluesbreakers. Their bassist at the time was 20-year-old trainee tax inspector John McVie. Then, in April 67, Green’s old Peter B’s Looners bandmate Mick Fleetwood became the Bluesbreakers’ drummer. Fleetwood lasted just two weeks before getting sacked for turning up drunk, but for a short time, the three key members of what would become Fleetwood Mac performed together. As a birthday gift to Green, John Mayall paid for a recording session. One of the tracks recorded at the session was given the title Fleetwood Mac.

By now, though, Green was getting restless. “I didn’t agree with the kind of material which was being played [in the Bluesbreakers],” he told Record Mirror. “It was becoming less and less of the blues. We’d do the same thing, night after night. John would say something to the audience and count us in, and I’d groan inwardly.”

With Mayall’s blessing, Green handed in his notice and started auditioning musicians for his own group. Mike Vernon had discovered an Elmore James-obsessed 19-year-old guitarist called Jeremy Spencer playing in a trio called the Levi Set. In June, Vernon arranged a support slot for the group with the Bluesbreakers in Birmingham. He also tipped Spencer off that Green was leaving.

“I met Peter at the Birmingham Metro Club,” says Jeremy Spencer now. “He wanted to hear me play because he wanted to form a new band and was intense about doing straight Chicago blues.”

Spencer auditioned, but didn’t think he’d passed. At the end of the night he was surprised when Green told him he’d got the job. Green then showed Spencer something he’d written in his notebook on the drive up to Birmingham. “It was like a prayer that said something like, ‘I can’t go on with this music like it is. Please have Jeremy be good, please have him be good,’” says Spencer.

Next, Green called Mick Fleetwood. The drummer was about to buy a set of ladders for his new job as a window cleaner, and he accepted Green’s offer. John McVie, however, was reluctant to give up a regular pay packet with Mayall, and turned Green down. As a temporary measure, Green hired 24-year-old trainee teacher Bob Brunning on bass. But it was evidence of Green’s lack of ego and belief that McVie would join eventually that he christened the new band Fleetwood Mac, the name they’d given to a song recorded at the Mayall-funded session.

“In my personal estimation, Peter Green was just about the very best blues guitarist this country has ever produced,” Mike Vernon said in 1994. Vernon lost no time in signing Fleetwood Mac to his new Blue Horizon label. The band made their live debut in August 1967 at the Windsor Jazz & Blues Festival. Eric Clapton strolled around backstage, sporting a Hendrix-style perm and draped in what one eyewitness thought was a bedspread. Spotting Green in T-shirt and baggy jeans, Clapton told him: “Peter, you’ll never be a star if you dress like that.” Green smiled, but said nothing. It was still all about the music.

A month later, as Green predicted, John McVie took over from Bob Brunning. Fleetwood Mac’s debut album – titled, against Green’s wishes, Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac – was released in February 68. It reached No.4 and stayed in the UK chart for a year. Mixing Spencer and Green originals and a cover of Elmore James’s Shake Your Moneymaker, it was, says Spencer, “a spontaneous release, which we all enjoyed”.

Green is less sure. “I don’t have fond memories of it, no,” he says. “Because I had to do the singing, and I really shouldn’t be doing it.” To listeners then and now, Green’s expressive voice is a highlight of the record. But he won’t be swayed. “In the traditional old jazz bands, they’d get one of the musicians to try a bit of singing. But he would only be talking. I categorise myself as like that. We used to play down the Flamingo. One night Ruby Turner got up and sang with us, and I was so relieved. I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be good if I could play like this all the time.’”

If Green felt insecure at the time, he hid it well. In May 1968, Fleetwood Mac’s single Black Magic Woman, a song about the guitarist’s sexual frustration, snuck into the Top 40. With barely time to draw breath, Fleetwood Mac were back in the studio in the spring of 1968 to make their second album, Mr Wonderful.

From these sessions came another single, the exquisite Need Your Love So Bad. But while the album itself bottled the band’s on-stage energy, it flagged song-wise. Still, the first peek into the darker side of Green’s psyche came on Trying So Hard To Forget: ‘I can’t stop my mind wandering back to when I was a downtrodden kid,’ he sang. ‘…I would spend most of my days running and hiding from the world outside.’

Fleetwood maintains that Green was haunted by the discrimination he’d experienced as a child. “He was an East End lad with a chip on his shoulder – a Jewish boy who got beaten up,” the drummer said in 1997. Green won’t elaborate. “It [childhood] wasn’t as bad as all that,” he says. “It wasn’t terrible.”

He may have felt downtrodden in his youth, but as a bandleader, Green had a clear idea of what he wanted. “He was incredibly ambitious,” Mick Fleetwood has said. But while the drummer and John McVie fell into line, Spencer was reluctant to follow Green’s instructions. “Peter would invite me to the studio with parts mapped out for me,” he says. “But I thought he should just go ahead and do them himself.”

“That’s because Jeremy didn’t like to be told what to do,” Green laughs. “He’d say: ‘Last time I was told that, I was at school!’ Jeremy wouldn’t play on my tunes, and I don’t know why.”

Spencer: “In hindsight, I should have been more accommodating.”

Although Spencer was now distancing himself in the studio, on stage he was a vital part of the show, with his bawdy jokes and impersonations of other pop stars. His attitude in the studio partly drove Green’s decision to bring in a third guitarist. Eighteen-year-old South Londoner Danny Kirwan was another Mike Vernon discovery. “Danny was a fabulous guitarist,” recalls Green. Whereas Spencer stayed out of Green’s songs, Kirwan wanted to get involved. Fleetwood Mac’s sound expanded for the better.

Despite his new recruit, Green played all the guitar parts on the band’s1969 single Albatross. The slow, almost ambient instrumental broke Fleetwood Mac out of the blues ghetto and on to daytime radio. Purists winced as their favourite band went to No.1. At the time, the group were touring America. Fleetwood says: “When we came back it was all over the music papers: ‘They’ve sold out!’”

But they also returned having tried LSD for the first time in New York. It was a watershed moment for Peter Green. The single, Man Of The World, reached No.2. This plaintive song is impossible to listen to without wondering how much lyrics such as ‘I wish I’d never been born’ related to their composer’s troubled frame of mind.

“The solo part is nice,” Green says now. “The instrumental break with the slide, in the Hank Marvin style, I thought was good.” And the lyrics? “It’s very corny in a way.”

He smiles and takes a sip of tea. Green talking down his talent is an occupational hazard for any interviewer, but there’s none of the false modesty most musicians have when dismissing their best work. Discussing the same song in 1969, Green said: “Words get in the way. The music is a more precise way of telling someone something.”

For Mick Fleetwood, though, Man Of The World was clearly “a cry for help”.

In early 1969, Green got a chance to live out his blues fantasies when the band took part in a jam-come-recording session with Otis Spann, Willie Dixon, Buddy Guy and David Honeyboy Edwards at the Chess Records studios in Chicago. But by the spring, as Fleetwood Mac worked on their third album, Then Play On, Green seemed to be in the grip of an identity crisis. As the 60s drew to an end, many pop musicians were seeking spiritual enlightenment. The Beatles had dipped into the teachings of the Indian guru Maharashi Mahesh Yogi, while The Who’s Pete Townshend had become a disciple of Meher Baba. Green now renounced Judaism and converted to Christianity. He grew his beard long and began wearing robes and a crucifix on stage.

Talking about his conversion now, Green’s eyes twinkle: “It’s a fantastic feeling. You bubble with it. All your problems are nowhere to be seen.” But a stipulation of his conversion was spreading the word of Jesus to people in the street. Easier said than done. “I think it was a soldier first of all, in Denmark,” he grins. “He went by, and I said something to him about Jesus. You’re stumbling at first. But then a chap went by in a suit, a city gent, and he slaughtered me.” He starts laughing. “He knocked it out of me. I can’t remember what he said, but I didn’t bother again.”

For Green’s bandmates, though, there was another, bigger, problem. “I decided to leave,” he says. “I bought a cello. I was going to learn cello. But the managers came to me and said: ‘Stay on for the boys, cos they’ve got families… and you’re doing so well writing the hits, so it would help.’ So I stayed on.”

Then Play On, released in September 1969, was their first record for major label Warner Bros. The writing was split between Green and Danny Kirwan. The latter’s choirboy voice contrasted with Green’s world-weary vocals. Their weaving guitars on Coming Your Way were a blueprint for twin-guitar rock bands such as Wishbone Ash. On Closing My Eyes Green sang the haunting line: ‘Some day I’ll die, and maybe then I’ll be with you.’ He told interviewers that it addressed the comedown from his failed attempt to convert to Christianity.

The album’s most startling feature, though, was its ambition. It wasn’t pure blues, but it was Peter Green’s blues: fusing Chicago with London; shades of English folk, Jewish and African rhythms. Whatever turmoil the guitarist was experiencing, he was, says Fleetwood, “determined to push the band forward”. And never more so than on the album’s centerpiece, Oh Well. The nine-minute composition was a masterclass in dynamics: a jabbing riff segued into a mini-symphony filled with Spaghetti Western guitars, orchestral drums and Green’s new discovery, the cello. Oh Well was split in half and released as two sides of the next single. It gave them their third top-five hit in less than a year. Fleetwood Mac appeared on Top Of The Pops, with Green singing about God and confusing the teenyboppers with his mad monk’s beard and gown.

Back on tour, in March 1970 Fleetwood Mac flew to Munich for a gig. They were met at the airport by delegates from the High-Fish Commune, a left-wing collective preaching free love and drugs. Green was smitten. “One of the girls was very attractive, a very famous model. Clifford [Davis, Mac’s manager] was very hurt when I walked off with them.” The model was Uschi Obermaier, a pin-up and actress who went on to have a long-running affair with Keith Richards.

Mac’s roadie Dennis Keane, who accompanied Green to the commune, later claimed they both had their drinks spiked with LSD. The commune’s leader later admitted inviting Green so they could get a message to the Rolling Stones. Fleetwood thinks Green stayed at High-Fish for three days. When they finally persuaded him out for the night’s gig, he was still tripping on acid. On stage, his playing became increasingly unhinged. “I did this thing with my guitar which made it sound like an air-raid siren,” he recalls. “I said to Mick: ‘What did you think of my playing?’ He said: ‘You were mad tonight… mad.’” He breaks off, laughing.

For many, Green’s spell in the commune was a tipping point in his mental decline. Back in England, he told the band that he wanted to give away all of his money. “Some of it, not all of it,” he corrects. Ever sensitive, he had apparently been moved to tears by TV footage of the recent famine in Biafra. “I just wanted to make a contribution. They [the band] thought I wanted to give it all away, but I wanted them to do it as well.” Green wrote cheques for large sums to a number of charities; the rest of the group and their management were reluctant to do the same. But the guitarist’s messianic vision persisted.

One night after a drug-induced dream, Green began work on a new song. With its sabre-rattling riff and Hammer Horror imagery, The Green Manalishi (With The Two-Pronged Crown) suggested a mythical beast of the kind that stalked Black Sabbath’s just-released first album. For its composer, though, ‘the green manalishi’ was a symbol for money. Released as a single, it went Top 10 in May. Perversely, a song about the evils of money was about to make its composer even more of it.

That summer, Green finally quit Fleetwood Mac. Fleetwood says: “He was good about it. He told us what he was going to do.” In August, the band announced his replacement: ex-Chicken Shack keyboard player and John McVie’s wife Christine Perfect.

Why did he leave? Green reacts to the question as if he’s never been asked it before. “I don’t know,” he shrugs. “I probably could remember if I tried… Let me see… I wanted to be free or something.” At the time, Mick Fleetwood explained that Peter “wanted to be just Peter Green. Not Peter Green of Fleetwood Mac.”

After his departure, Green recorded an improvised solo album, 1970’s The End Of The Game, and went to the US to spend time at Goddard Free College in Vermont, “just to hang out and do whatever I like”. Surrounded by beautiful girls, he took a hit of LSD. “But I still haven’t returned from that. You’re not allowed to return.” He hesitates. “It’s like someone’s playing with you.”

Back in England, he carried on living with his parents in the house he’d bought in suburban Surrey, occasionally jamming with other musicians and telling the press that there had been “no challenge” in remaining with Fleetwood Mac. When Spencer quit the band in 1971, Green stood in for a few US shows. But the albums the group were making without him – 1970’s Kiln House and the following year’s Future Games – held little appeal. “I couldn’t identify with it,” he says. “It wasn’t blues, was it?”

According to Green, he took LSD once more after Vermont. “It was in Surbiton. I listened to Donny Hathaway all night long. It was a beautiful night.” But the experience left him “halfway between this” – he holds his hands apart in the air as if gesturing towards something unseen – “and that. And that’s no good.”

Some close to Green maintain that LSD was the trigger rather than the cause of his problems. “I think there has been a bit too much blame put on it,” says Jeremy Spencer. “Unfortunate mental afflictions have been around for centuries before the existence of drugs.” In the mid-70s, Green was diagnosed with schizophrenia.

As he disappeared from public view, the band he started were becoming one of the biggest in the world. Did he ever listen to Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours? “Yeah, I like Rumours. Just as well. It sold about 22 million – just last week,” he chuckles.

The contrast between Mick Fleetwood’s and Peter Green’s lives since 1970 is not lost on the man whom Green spared from a job as a window cleaner. Interviewed in 1997, when Fleetwood was touring the re-formed Rumours-era band around the US, the drummer told me that he “wanted to help Peter in any way I can”. The air of unresolved business – even guilt – was palpable.

You can still hear Peter Green’s blues in the music of Led Zeppelin, Gary Moore, Black Crowes, Rory Gallagher and Brian May, to name a few. In 1978, Judas Priest covered The Green Manalishi and turned it into the heavy metal song it always threatened to be. Green’s style of guitar playing – the sustained notes, the trembling vibrato – has inspired hundreds of guitarists. The man who never wanted to be in competition with Eric Clapton has been described by Clapton as “a truly phenomenal player”; more recently, Oasis’s Noel Gallagher has cited Fleetwood Mac’s reluctant frontman as one of his favourite singers from the 60s.

After a stint of recording in the 1990s and a 2009 tour billed as Peter Green And Friends, Green spends most of his time now at home, listening to the radio and his vast collection of CDs. He still plays with the members of the Peter Green And Friends line-up, but only in a rehearsal studio; there are no current plans for gigs or tours. Often, when he’s on his own, he picks up the guitar and puts on a recording of his music. “I play along to Peter Green And Friends,” he smiles.” I sit on the couch – with a speaker here and a speaker there – and I play along with it.” He pauses and offers another fleeting pop-star smile. “Nobody’s watching me, so I can’t go wrong.”

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 174, July 2012