Maverick. Visionary. Prog’s perennial Renaissance Man. Punk-approved eccentric. After more than 50 years of active service in progressive music, Peter Hammill has earned all these titles and more. Always positioned to the left of the prog mainstream and seemingly impervious to the passing of time and trend, he’s amassed an extraordinary catalogue of music, both as a solo artist (36 studio albums and counting!) and with the legendary Van der Graaf Generator: the band he co-founded in 1967 and that currently exists as a trio, with Hammill alongside Hugh Banton and Guy Evans. By any sane reckoning, he’s one of the most important and influential figures in the history of prog. But what’s less frequently acknowledged is that Peter Hammill’s music, whether solo or with Van der Graaf, sounds like absolutely nothing and nobody else. In fact, it never has.

After a comparatively long gap between solo records, Hammill is to release his first ever covers album, In Translation, in May. It’s a highly revealing piece of work: a collection of mostly European songs, including works by Mahler and Rodgers and Hammerstein, translated by the man himself and reimagined with his customary skewed flair. Both a self-evident love letter to Europe and a wide-eyed experiment in dismantling and reconstructing other’s work, In Translation sounds entirely unlike anything else one might hear in 2021. And that’s exactly how Hammill likes it.

“I’m completely comfortable with that,” he tells Prog. “I’ve never really wanted to join in. I suppose the entire career has really been about trying to do something and getting it slightly, wonkily wrong. When I started writing proper tunes, I guess the subjects of the songs were a little bit out of the ordinary, and I didn’t want to repeat things, so very early on I veered away from verse, chorus, verse, chorus. I can’t explain why, but from a very early stage I was taking a few turns to the left, away from the main drag.”

One of the great joys of Peter Hammill’s music is how relentlessly inventive and unpredictable its creator has been over the last five decades. Having applied his singular vision to everything from tear-jerking ballads to abstract noise, he remains incredibly hard to pin down sonically. Interestingly, Hammill is endearingly unsure where his musical vocabulary comes from. He cites his parents’ love of musicals as an obvious starting point, noting that he grew up hearing West Side Story blaring from the family record player and that “it must have seeped in somewhere”. But the real starting point for his fantastic musical voyage came when Hammill was packed off to boarding school as a child, ended up singing in the choir and had a moment of revelation that set his artistic wheels in motion.

“It was my first actual experience of, ‘This is music, this is great!’” he recalls. “I was a treble, at the junior school, going up to the main school for the Hallelujah Chorus. I’d only known the existence of trebles and altos at that point, so to suddenly be in a stall with basses and tenors, I thought that was absolutely fantastic. That was the first time I got that feeling that, wow, music is fantastic stuff. My voice broke not long after that and there were a couple of years when I wasn’t that involved or interested in music, and then British beat groups happened. I became super-keen on that, and then the blues thing too. I became enthused about the whole thing, but I didn’t think I would be doing it for the rest of my life.”

As it turns out, Hammill has made music for his entire life, although he cheerily admits that his first bona fide musical efforts were somewhat wide of the desired mark and could easily have stopped his career dead in its tracks.

“As a result of the beat groups and finding out about blues, I started to write these desperately poor blues songs, without any of the life experience required!” he says with a chuckle. “I had a harmonica, then eventually I got a guitar and started doing the same thing on guitar. I guess I was 14 or 15. By 16 or 17, I’d started writing some tunes, some of which eventually turned up in the body of work, not with the original lyrics, but the tunes stuck.”

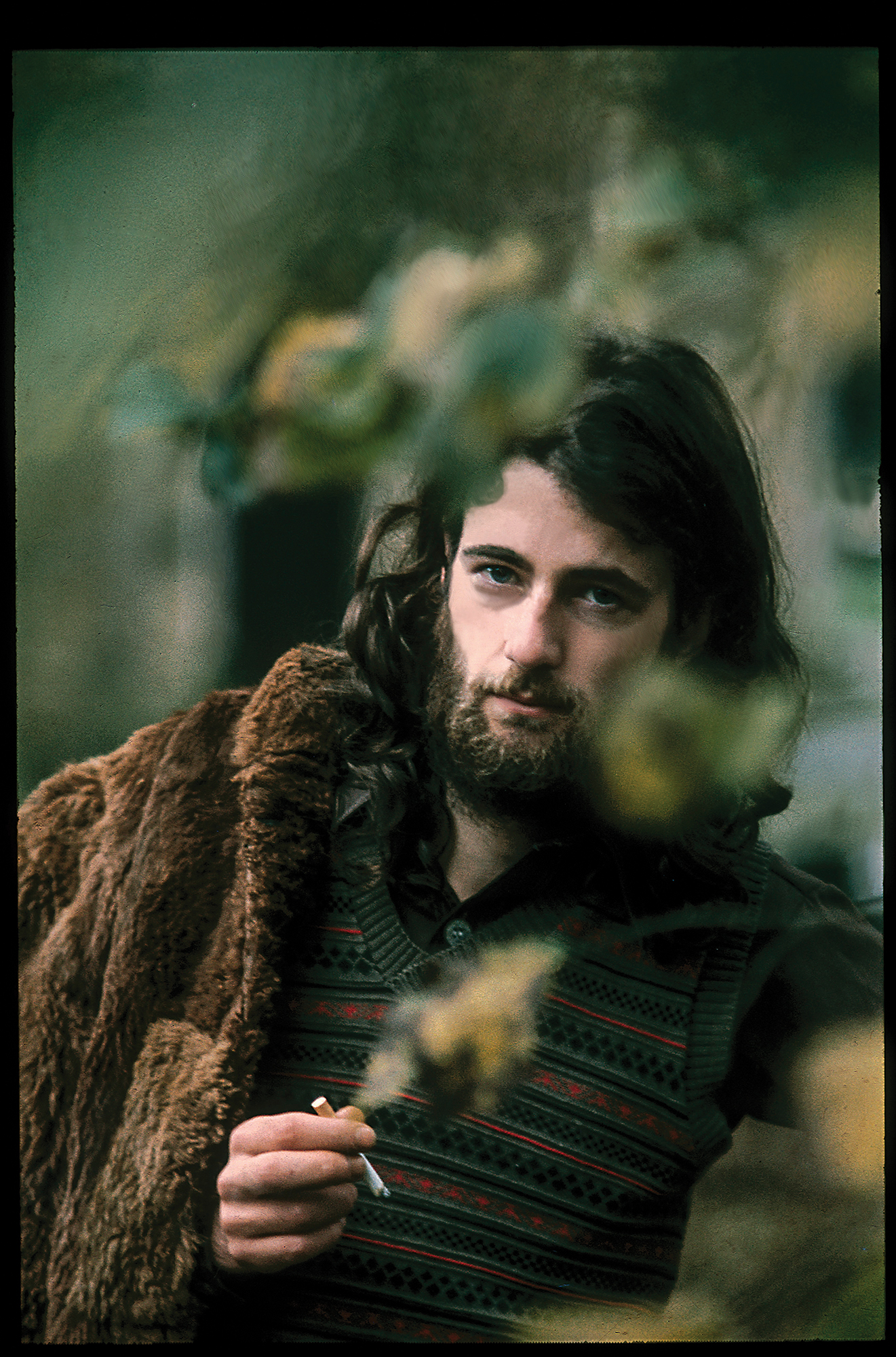

Freed from the blues, Hammill’s next move would prove to be the most important he would ever make. Arriving at Manchester University in the mid-60s, he swiftly joined forces with fellow aspiring musician Chris Judge Smith, and formed Van der Graaf Generator. At that time, the chances of having a successful career as a musician were slim at best, and yet after barely a year, the band were offered a contract by Mercury Records. Sensing an opportunity that may well have not been repeated, Hammill grasped the music biz nettle and set forth on a career he had never really expected to have.

“It was a dreadful contract, of course, but Judge and I decided we’d leave university and carry on and do it. We were super-naïve. But who knows? When I got to university I actually did try to change to a drama course and I wasn’t accepted for that, which was totally fair enough! [Laughs] I was a pretty wonky youth, to be honest. But meeting with Judge and having all that enthusiasm, things just happened onwards from there.”

What might he have been had he not become a musician?

“Well, I do think it would’ve been writing in one way or another. Whether that would have been novels or journalism, I don’t know. One of the ideas on the course I was doing in Manchester, which was Liberal Studies & Science – and how 60s can you possibly be? – was that people would emerge from the course knowing enough about both science and society to get involved in the civil service or decision making or maybe in scientific journalism, to explain things to people. Back then, popular science simply wasn’t a thing. Now there are lots of popular science books, explaining physics and all that kind of thing. Maybe that would’ve been that kind of territory that I’d have gone for.”

This year brings both Hammill’s new solo record and the prospect of a huge and long-awaited Van der Graaf Generator reissue campaign, including a colossal box set and remixed, vinyl editions of the band’s classic albums, the revered Pawn Hearts and Godbluff. Meanwhile, the current Van der Graaf line-up are finally due to play some shows later this year and in 2022, after rescheduling everything for reasons that hardly need explaining again here. There is, it seems, a lot going on, and Hammill’s dual careers continue to flourish, consistently defying the odds. Sustaining one career is pretty impressive, but keeping two significant plates spinning for the best part of 50 years is nothing short of miraculous.

“Initially, while Van der Graaf was going, I thought they were two very different things. They weren’t really in competition,” says Hammill. “Back then, I don’t think any of the others thought they were in competition either. Although it had a connection to Van der Graaf, [Hammill’s 1971 debut solo album] Fool’s Mate was obviously not remotely in Van der Graaf territory, even though the guys were playing on lots of it, along with lots of other people. But it was never a competition with the band and Fool’s Mate was material that the band was never, ever going to do. Then I made Chameleon In The Shadow Of The Night, The Silent Corner And The Empty Stage and In Camera, and those were all when Van der Graaf wasn’t in existence. So there’s always been a clear divide.”

Clear divide or not, there was one moment when Hammill’s solo career and his work with Van der Graaf plainly overlapped. His fifth solo album, 1975’s seminal Nadir’s Big Chance was recorded by the band’s classic line-up of Hammill, Hugh Banton (bass/Hammond), Guy Evans (drums) and David Jackson (saxophone), just after the quartet had made the decision to reform after a three-year hiatus. Musically ahead of its time (and often cited as a proto-punk classic), it set the tone for the Van der Graaf albums that would soon follow, while also pushing Hammill ever further from the mainstream.

“Nadir… is a very specific case. Obviously by the time it was recorded, we knew we were going to be doing Van der Graaf again, and already we knew a lot of the tunes that we were going to be doing,” Hammill explains. “Again, the songs on Nadir… were tunes that were never going to be played by Van der Graaf. And yet, it was the first thing we recorded together having decided to reform and it had a significant influence on the later work. So much of it was done pretty much live, and we did Godbluff and Still Life as a result of that.”

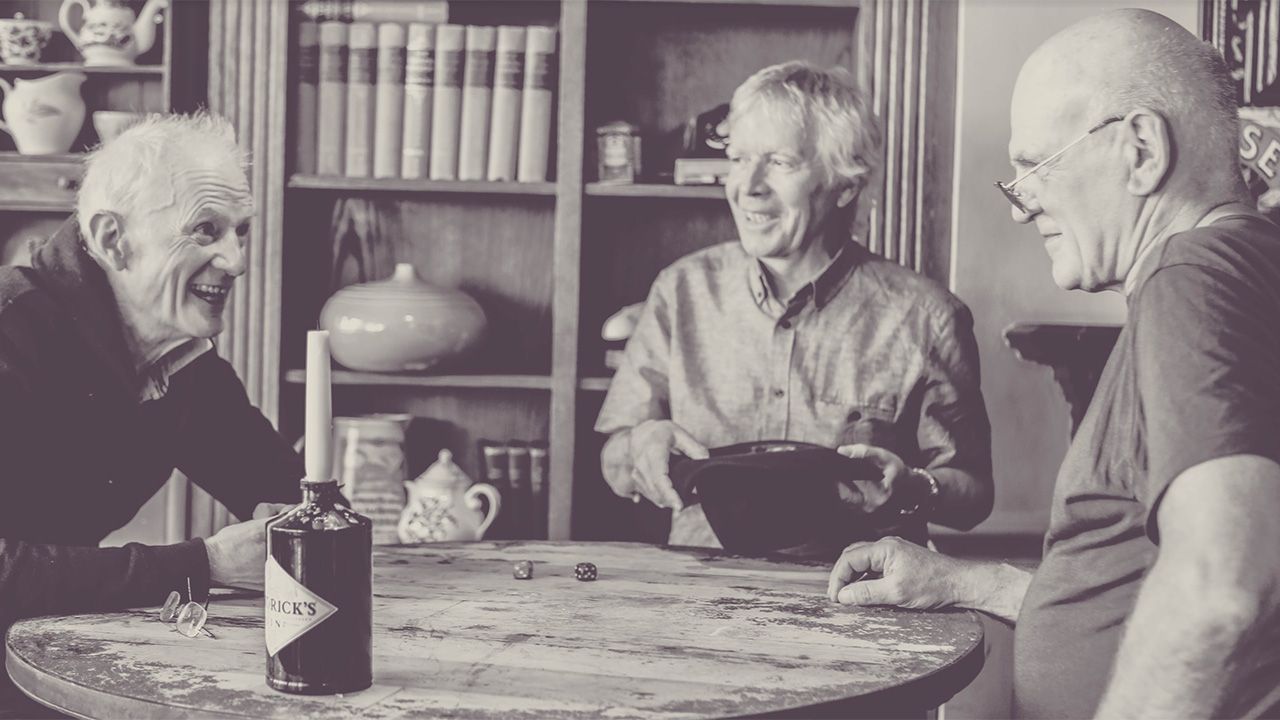

Still going strong after all this time, Hammill’s relationships with Hugh Banton and Guy Evans have been fundamental to both of his careers. As he notes, the bond between the three of them has become even stronger in recent times, not least since they decided to reinvent Van der Graaf Generator as a trio, following the departure of David Jackson from the reunited line-up in 2006.

“It’s been a lifelong thing with Hugh and Guy, yes indeed,” says Hammill. “It’s pretty extraordinary, I think. To have this late flowering of a career is quite odd. To do that and then find ourselves reduced to a trio, but actually needing, for our own validation, to find out whether it could actually work as a trio. Then, when it did work, it just became a necessity to carry on and see what else was possible. It’s pretty bizarre stuff, for chaps in their late 60s. But particularly over the last 10 years, we’ve been incredibly supportive of each other. We’re very different people and we have different interests, but we’re united in the common goal of playing together, doing the right thing and, of course, not compromising.”

It’s a testament to Peter Hammill’s unerring ability to do the unexpected that he is, at 72 years of age, releasing his first ever album of cover versions. In Translation comprises renditions of 10 songs by European and American composers and songwriters, all but three have been translated into English by Hammill himself, and rearranged in such a way that they fit snugly into the freewheeling aesthetic of the singer’s more recent creations. It’s a beautiful, emotionally potent piece of work, but it’s also a very plain and pointed love letter to Europe, recorded as the UK’s relationship with the continent has been irrevocably changed. Hammill admits that part of the motivation behind In Translation has been to pay tribute to Europe, almost in defiance of the prevailing Brexit winds.

“Obviously, as I was doing it, this Brexit cliff has been looming, waiting for us to fall off it,” he says, sounding genuinely incensed. “But having finished the album, I did realise that I wouldn’t be able to translate these songs if I didn’t have an understanding of those cultures. I wouldn’t be able to translate if I hadn’t learned the languages while having this great experience of being a European, travelling around Europe. And yeah, this is a privilege, which is not going to be there for my children and grandchildren. So it’s a love letter to all of that, indeed.”

Hammill and Van der Graaf Generator have an enduring bond with Europe that stretches back to the late 70s. Although relatively well-known at home, it was across the channel that the band would find their most vociferous support base, with Italy proving to be the country that loved Van der Graaf more than any other. For Hammill, those first experiences of travelling through the continent had a profound impact on his worldview.

“It was all a brave new world to us,” he says. “There wasn’t the sense of homogeneity in Europe that there now is. Shops were different. The food was different. There wasn’t even a Vietnamese restaurant on every street. So when you went abroad, you knew you were definitely in a different country. For me and for all of the others, there has always been a sense that we’re privileged to go and work somewhere and to be a part of the life of that particular country and culture temporarily. We all felt it gave you the chance to ask questions, like, ‘Why is that like that?’ or try to understand the culture directly by talking to people.”

Hammill takes a deep breath, audibly exasperated: “You know, it’s been a tremendous privilege to be able to travel, and that’s one of the things that’s so fucking piteous about the whole Brexit thing. It’s clearly the design of this government to deny that view on other cultures, and to be directly anti-culture and anti-European, so that nobody will ever know that there’s a world outside. Right, rant over!”

Another unfortunate side effect of the pandemic has been that Hammill hasn’t been able to make his annual trips to play shows in Japan and, most importantly, Italy. Uniquely among nations, Italy welcomed Van der Graaf Generator as bona fide rock stars when they arrived for the first time in 1972.

“That’s the place where we’ve done most of the touring and had most of the success, yeah. Our tour manager did a fantastic job of preparing the way, along with a couple of journalists and magazines. So that was the setup, and obviously then we had to deliver. We were right for Italy and Italy was right for us at that time. The stars were aligned, basically. Obviously there’s an operatic element to the Italian soul that likes big gestures, and we were capable of big gestures at that time.”

Having been blown away by the reception in Italy, Hammill gradually began to immerse himself in the country and its culture. He notes today that he’s been to Italy virtually every year since that first trip, and that learning the language has been one of the great joys of his life, and not just for the purposes of translating song lyrics.

“I did a solo tour in Italy after Van der Graaf broke up the first time, and if I was going to speak to anyone other than my tour manager, I needed to start learning some Italian,” he recalls. “I’d studied Latin at school and that was useful, and I’d done some French so that was useful too. I began to have some understanding about how the Italians use their hands, which is obviously crucial, and so that’s how I started speaking Italian, in a very basic way. By the time I’d done that, I’d plunged into the swimming pool of language.”

Given that it comprises songs from an assortment of noted and more obscure European songwriters, readers could be forgiven for thinking that In Translation indicates a similarly deep love for European music. But just as his songwriting appeared to emerge from nowhere in the late-60s, so Peter Hammill’s music continues to evolve and mutate without any significant outside musical influence whatsoever.

“When it comes to European music, to be honest, I’ve never been much of a listener to other people’s music,” he says. “Touring around Italy, we’d hear radio and Italian pop music as much as our contemporaries. That’s interesting, because I do think there are some hidden chords that the Italians have that we don’t have access to, and that’s why Italian pop always seems to have a particular character. They stick chords together in a fascinating way. I Who Have Nothing [from In Translation] is a case in point – that’s an Italian tune, bang on, I don’t think it could come from anywhere else. But was it an influence? No, because I didn’t listen to it that much.”

If he listened to lots of other people’s music, does he think his music would come out differently?

“I honestly don’t know. I like making music, really. The stuff I’ve listened to over the last few years has generally been classical, which is outside my territory. If there’s something that’s remotely near my territory, which obviously has become broader and broader over the years, I’d rather be making it than being a recipient of it. That might sound a bit egotistical but that’s just how it is. I get the joy from making it, rather than taking it in from somebody else.”

Standing apart from the crowd can be a hazardous business, but Peter Hammill has somehow always made it look easy. Famously, he was the only major figure from the progressive rock world to be given a free pass by the otherwise unforgiving punk rock scene that exploded in the UK in the late 70s. Nadir’s Big Chance is often cited (somewhat dubiously) as one of the first punk records, Sex Pistols frontman John Lydon was (and is) a fan, and the late, great Mark E Smith of post-punk legends The Fall once asked him to produce his band’s next record, citing Hammill’s 1978 album The Future Now as inspiration. Not surprisingly, Hammill has never much fancied getting a Mohican and takes such things with a pinch of salt, but he does admit that the parallels between his own music and the untutored racket of punk do exist.

“I don’t entirely buy into the idea that Nadir… was the start of punk, but it was important in terms of the Van der Graaf line-up that was coming on, the band of Godbluff and Still Life,” he states. “We were doing complex stuff, more than just three chords, but we were doing it with a degree of aggression. A song like Arrow, it’s all over the place in terms of time signature and so on, but if you strip it down to what it is, it’s really aggressive, with screaming vocals. That’s not that far away from punk, is it? Then there was the Van der Graaf when Mozart [bassist Nic Potter] came back. At that point we were playing for survival, and it was ridiculously aggressive. I think we were pretty much in with the zeitgeist there.”

He’s absolutely right, of course. Listen to Vital, the visceral Van der Graaf live album recorded at the Marquee Club in January ’77, and witness the sound of a brutal and wilfully uncommercial band making a terrifying din that still makes most punk rock records sound like Mantovani. As much as it may be hard to equate the well-spoken, articulate polymath we know and love with the spirit of pogoing and snot, there is undeniable kinship in there somewhere. Perhaps Hammill flourished during the punk era because it was so obvious that, unlike many punk bands, he was an authentic rebel.

A few years later, however, punk was a spent force in the UK and the 80s were in full swing. Most prog bands that had thrived during the genre’s heyday were either pursuing an overtly polished and commercial course or not making music at all. Peter Hammill simply carried on making solo records, eager to explore a new decade’s possibilities. In 1983 he was offered the main support slot on a tour with Marillion, a young band that were stridently recreating the sounds of the early 70s and, somewhat against the commercial grain, building a huge, passionate fanbase in the process. Many artists in Hammill’s position would have taken a pass, preferring not to acknowledge the arrival and potential threat of the new guard, but instead he grabbed the opportunity: to present his music to some new people, and confuse the hell out of them.

“At that time I hadn’t toured around Britain for a long time, so obviously it was an opportunity to get through to people. The Marillion chaps were all really pleasant and everything, but it was a career move to some extent. I was doing it with John Ellis [guitarist who co-founded punk band The Vibrators and has worked with Peter Gabriel among others] and about half of the set would be two guitars and voice, but I also decided that we’d do some of the crazier stuff. So half of it was ordinary-ish tunes like Happy Hour [from 1982’s Enter K] and then the other half was us playing over these cassettes of musique concrète elements. It didn’t go down very well with the bulk of the Marillion audience! [Laughs] There was, however, part of the Marillion audience who obviously went, ‘Hang on, what’s this all about?’ There are loads of people who saw me for the first time on that tour and have followed ever since, which is interesting, I think.”

Could it be fair to say that Hammill derives almost as much satisfaction from confounding people as he does from entertaining them?

“Well, in some ways it was an anti-career move too. There were some nights when there was conspicuous disagreement with the fact that I was sharing a stage with Marillion, from the audience! But it was probably not as extreme as when I was supporting Peter Tosh, in Italy, in a football stadium, unannounced.”

Yes, you read that right. In 1980, Peter Hammill volunteered to act as main support to Peter Tosh, reggae legend and former Wailer, on a tour of football stadia around Italy. Aside from creating one of the most mind-boggling line-ups of all time, the shows proved to be an unexpected success for all concerned, with Hammill apparently relishing the gigs’ confrontational vibe. Frankly, it’s hard to imagine anyone else from our world doing the same.

“At the start of each show there’d be chaos because I’d go on, and half the crowd would be just reggae people and they’d be whistling and shouting me down,” he recalls, cheerily. “Meanwhile, another half of the crowd was bellowing, ‘Don’t you know that’s Peter Hammill?’ So I’d be singing through all these catcalls for 10 minutes, but eventually I’d get through. So that was even more extreme than the Marillion reactions. The Tosh crew really didn’t know what to make of me at first, but eventually it was [credible Jamaican accent] ‘Ah, Neil Diamond, man!’ [Laughs] I figured that was close enough. So I have not been averse to putting myself into adversarial positions sometimes.”

Back in 2021, Hammill finds himself in an enviable position. Although he’s never made a fortune from his music, he’s ticked along consistently for decades, almost entirely self-sufficient and with an unerringly loyal fanbase. In 2003, he survived a heart attack and swiftly returned to action, reuniting Van der Graaf Generator and becoming even more productive as a solo artist. (“It’s remarkable how quickly one’s sense of immortality returns!”) For the last few years, Hammill has made albums completely alone, building songs from scratch in his home studio and drifting ever further away from musical convention. In fact, he seems to be enjoying the creative process more than ever and taking more leaps of faith too, as showcased via recent collaboration with Swedish art rock collective Isildurs Bane and UK psychedelic prog act The Amorphous Androgynous. With Van der Graaf Generator poised to return to action in the near future, prog’s premier maverick, visionary and eccentric is as busy as ever and thrilled to have done, as he puts it, “whatever the hell I like, for 50 years”. He’s even more excited about what happens next.

“I’ve just started work on a new solo album, so that’s underway now,” he concludes. “This is simply what I love doing. I don’t want to presume that I’ll always be able to find songs, because it’s actually still a mysterious process to me. I don’t want to presume that I’ll always find subjects for songs, but right now they’re still coming. Let’s just say that it’s very unlikely that I would be a happy retiree!”

This article originally appeared in issue 119 of Prog Magazine.