In the winter of 1989, a few of us were in the studio one day when we got a call from Mensch. “Steve’s in trouble. He was found unconscious in a bar in Minneapolis, and he’s been rushed to a hospital there.”

We flew out to see him immediately. It was me, Joe, Mutt and Tony DiCioccio, and either Peter or Cliff. I remember turning up at the Hazelden Addiction Treatment Center, north-east of Minneapolis. The patients looked like the cast from the film One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, including the large Native American. We were each asked by the doctor to write a letter to Steve voicing our opinions and how we felt about all of this. But then the doctor said, “OK. Now I need you to read it to him.” The doctor also told us about enabling and that if we loved our friend we would have to confront him via intervention. I read my letter first. We all sat in a circle and we told him, “Steve, you’re scaring the shit out of us.” He sat there with a cigarette taking it all in. Mutt gave him a big hug; then we all hugged him and told him that we loved him. That was a very tearful and emotional experience for all involved, especially when the doctor explained to us that about 70 per cent of alcoholics who get to this level usually end up getting killed either by accident or overuse. This was just about as serious as it could get. This was something very different.

The doctor also told us that the alcohol level in Steve’s blood was 0.59. That didn’t really mean anything to us, until he explained that it was a 0.41 level that had killed John Bonham from Led Zeppelin. Then he went into detail about just how dire it was – more statistics about alcoholism, the physiological and psychological toll on the body, everything. Then family members and friends of alcoholics at the facility came in with their stories.

With our support, Steve went to another rehabilitation centre, this time in Tucson, Arizona. We told him to take a six-month sick leave and get healthy – that we’d keep working on the record and that, as soon as he was able to, he’d get back in the fold. It wasn’t long afterward that Steve met Janie Dean, another patient who was being treated for heroin addiction. Steve thought this would be great – they could help each other cope with each other’s addictions.

But, as anyone familiar with addiction knows, this was a bad fucking idea. They both left rehab and continued aiding each other’s addictions. We didn’t think it could get worse, but it did. It became almost impossible to keep track of Steve’s whereabouts or what he was doing.

The morning of 8 January 1991, I got a call from Cliff.

“Phil,” he said, “I’ve got some bad news. Steve died in his sleep.” It was exactly like the dream I had had. What had happened was that he had been drinking and had cracked a rib earlier on. The doctor told him not to drink while taking his pain medications. He drank anyway. The coroner’s report, I believe, read that it was due to a swelling of the brain. Janie had found him at his Chelsea house in London. The very surreal part about it for me was that I had expected a phone call like this perhaps from Cliff for the past five years, so I wasn’t shocked but instead freaked out. This was such a huge psychological blow for all of us. After Rick’s accident and amazing recovery, we hadn’t thought we’d ever have to confront anything like this but now one of us had died. It’s incredible that we never prepare for death while we’re young, almost as if we have this immortal streak in us. Janie was not to be of this world for much longer either. We heard a few years later that she also died from drug use.

Initially, I didn’t even want to be in the band after Steve passed. It just didn’t seem right to replace him. Steve Clark had been such an integral part of the band; he had been instrumental in creating the sound and was part of this family that we had. I mean, you wouldn’t replace a brother if he died. It’s funny – many people have said to me over the years, “It’s great you kept Rick after his accident,” as if it’s only about being in a commercialized music group. I have to say, I always feel quite insulted by that statement. We’re a lot deeper than that. We chose to be together in this band, and we’ve spent more time together than most blood-related families. If you consider it, kids usually leave their parents’ households in their twenties if they’re lucky. But we have thirty-something years together under our belt.

With all this being said, one morning Joe and I were in the kitchen and I said, “I’m done. I don’t want to do this any more.” One of us had gone and the gang was broken. He said, “Well, what do you want to do?” I told him I’d rather be a plumber. (A bit ridiculous, considering I can barely turn a faucet off. But you get the idea.)

But Joe talked me off the ledge, saying, “Don’t become a plumber. We owe Steve for all these songs we wrote together on this record. He’s still part of us. Let’s, at the very least, honour him and finish what we started.”

So I did what Joe suggested: I threw myself into work. For weeks after Steve’s death I would go to the studio and play guitar and listen to the parts that Steve had done on our demos – I had to learn his parts and then play them verbatim along with my own. It was just me and Steve in that room. It felt as if there was a ghost in there with me as I played his parts over and over. It was almost as if he was still alive. It was just so weird. But I knew how to put his spin on all those notes. I lost myself in trying to sit there and play along with Steve, working as hard as I could to create something he would have been proud of.

I never really gave in to the emotion, though all that time I was dealing with Steve’s death. I had put up many walls so I wouldn’t have to deal with it or accept it. It wasn’t until about three months later, when I was stuck in traffic on the 101 freeway in Los Angeles and the Rolling Stones’ Waiting on a Friend came on the radio that I burst into tears. I pulled over to the side of the road and cried like a baby. I couldn’t stop. That was really the moment that I began to deal with the loss of my best friend. To this day, I continue to have dreams where Steve appears and we just talk as if nothing has changed. It feels totally natural, and that’s fine with me.

This was the first time anyone in the band had suffered the loss of someone that we saw every day. Although we were all trying to process this, there was something that really started annoying me. It was the fact that when Steve’s funeral was announced, all of a sudden, everyone started caring about Steve – from total strangers to people who knew him on the fringe. I was so pissed about this that I decided not to go to the funeral. When Steve needed help, only the people really close to him were there. As soon as he died, everyone jumped in with their “I knew Steve” stories, not trying to help with his addiction but simply based on trying to hang out with a rock star. The floodgates opened and all the sycophants started pouring in for the funeral, which confirmed my decision not to go. I know Steve would have been with me on that.

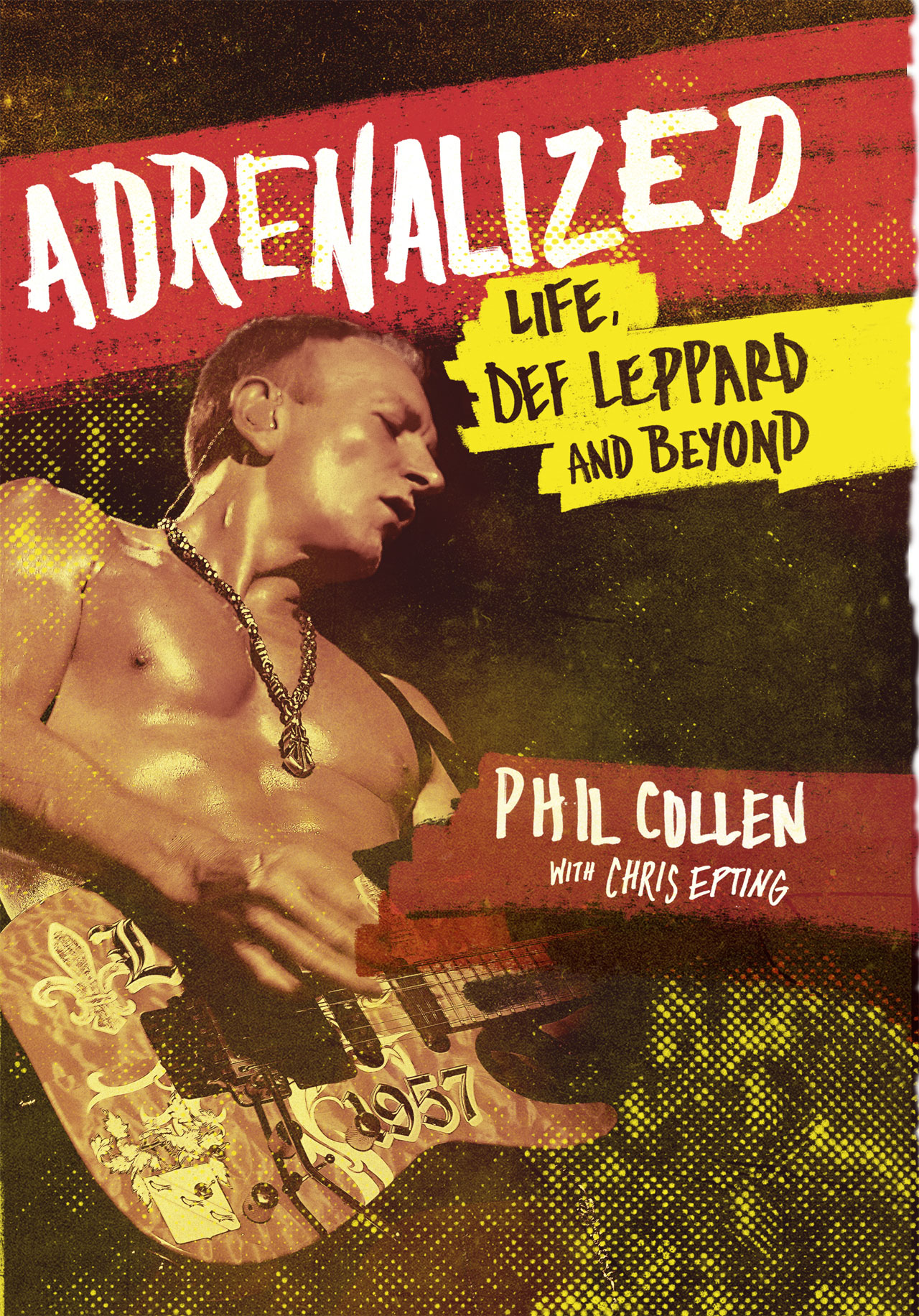

Phil Collen’s Adrenalized: Life, Def Leppard And Beyond is out now on Bantam Press, and costs £18.99.

Def Leppard’s new album is to be released as a Classic Rock Fanpack on October 30, four weeks before the regular CD is released. The Fanpack will include the CD (including an exclusive bonus track), a 116-page magazine featuring all-new interviews with all five band members, all-new photos and a track-by-track guide to the album, a series of collectable art cards, and a metal Def Leppard keyring. Pre-order now.