The early days of Thin Lizzy were the fun bit,” says Gale Claydon. “But that doesn’t mean they were simple. Phil was a really complex person.”

In the early 1970s, Belfast-born Claydon was Phil Lynott’s live-in girlfriend; the person that knew him best, away from the stage and gang of rootin’, tootin’ good-timers he surrounded himself with even before he became famous. Gale has always refused requests for interviews about her years with Phil. Now, on the 30th anniversary of his death, she has broken that silence.

“We were just kids when we met,” she sighs. “I was 18, he was 20. It was simple: Phil had a dream. We all had dreams. It was going to be wonderful. The world was going to be great.”

Gale was with Phil when Thin Lizzy signed with Decca Records and moved to London in 1970. There for those first three albums Lizzy made for Decca, none of them hits, but all pointing to the direction they would later find success with. But as Gale suggests, the story of Phil Lynott – the real Phil Lynott – is far from straightforward.

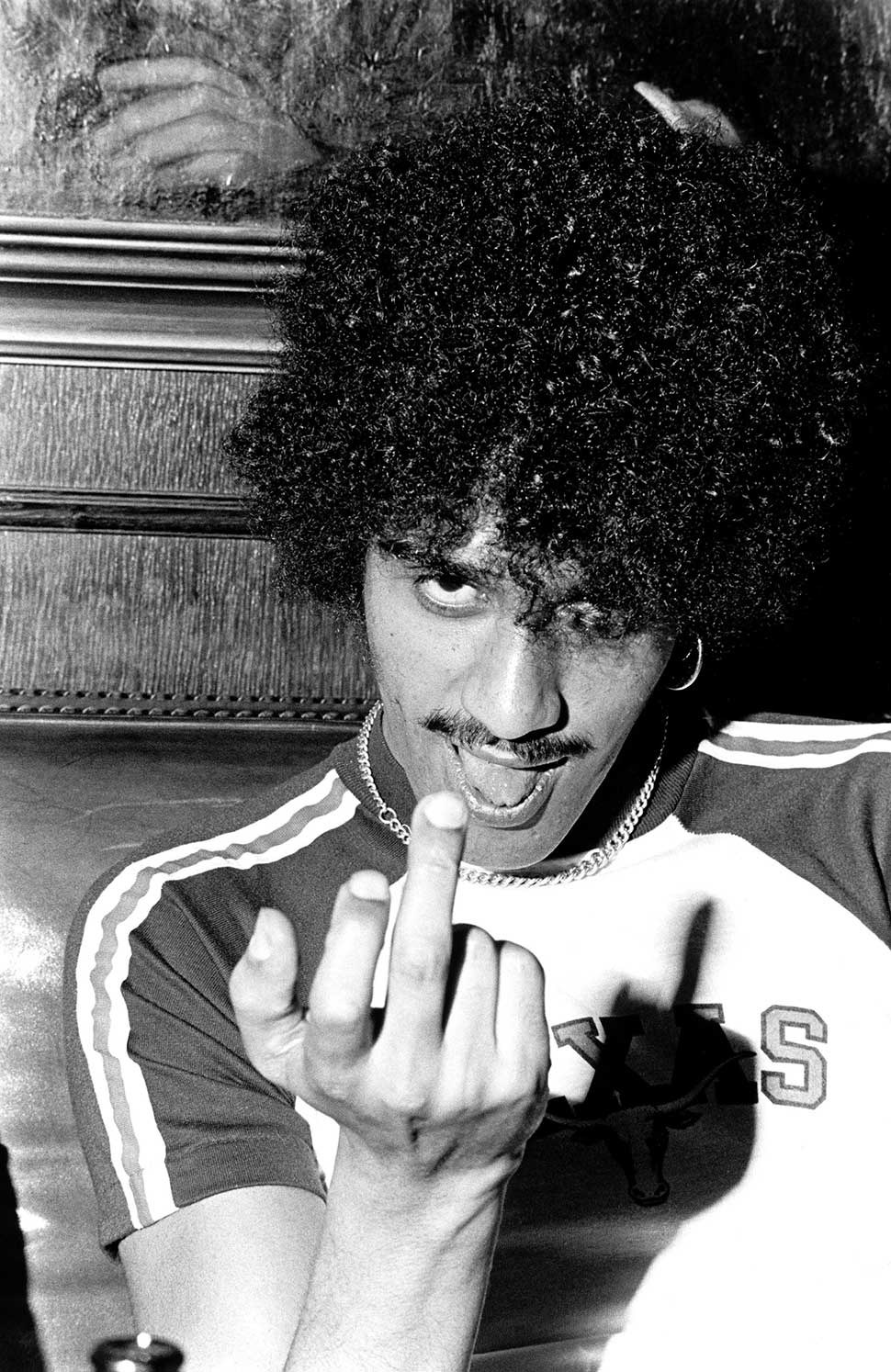

“Everywhere I read about him, he’s a caricature: a Playboy of the Western World. The leather, the afro, the wild boy. Well, he wasn’t. He was so complex. Not how people picture him now.”

But then that was ‘Philo’ for you. Or “Philip, to my friends,” as he once told me, though I rarely heard anyone address him so. The life and soul of the party with the wary brown eyes. Always good for a joke and a toke, but who always kept that little bit back from you. A complicated man with a tangled background – half-black, half-white, part Catholic, part God-hater – who would write poetry one minute, knock you out cold the next. A man who would slap you on the back, but never fully trust you.

“I don’t think Philip trusted anybody his whole life,” says Gale, who went on to become a television producer in the 80s and stayed in touch with Lynott until the end of his life. “But then you look at his upbringing and you understand why. Why he was so insecure, so angry and so determined to bloody make it. He simply had to.”

Or die trying.

The illegitimate product of an affair between his Irish mother Philomena Lynott and Brazilian father Cecil Parris, Phil was born in West Bromwich in 1949. He was four when Philomena sent him to Dublin to live with his grandmother, Sarah Lynott, while she stayed in England and worked. Philomena recalled how her mother fainted when she first saw a picture of her “little black baby”.

“The stigma of not being married was a big thing in Ireland back then,” says Gale, who was close to Philomena (or Phyllis, as she still calls her today). “But to be unmarried with a black baby… was just unheard of.”

It was something Lynott himself would be made painfully aware of every day. “I wasn’t an outcast exactly,” he said. “But I knew I was the only one around like me. I wasn’t allowed to forget it.”

“He was the only black kid in the whole neighbourhood, let alone the school,” recalls Lizzy drummer Brian Downey, who first met Lynott when he was nine. “Phil would get picked on, called the ‘N’ word. But he could handle himself. He used to go to the boxing club. So because he had that reputation, people would back off him.”

There was another side to the teenage Lynott too: one that was shy, gently spoken, devoured Irish history books, loved the plaintive folk ballads of the mythological Celtic past, and would reference 19th-century Dublin poets like Clarence Mangan, who had influenced James Joyce.

“Phil was the most nationalistic person I ever met in my whole life,” says former Lizzy guitarist Scott Gorham, who met him in 1974. “To hear Phil speak, Ireland was the greatest place in the world. He knew all the dates and names and what battles happened. He’d drag me along to some well in Ireland and go: ‘You know what happened here?’ I’d be like: ‘You know what? I don’t really give a fuck.’ He’d be like: ‘Well I’m gonna tell ya anyway!’”

“He was a funny fucker, too,” says Downey. “He had that Irish way of telling a story, seamless. You’d be spellbound listening to him.”

It wasn’t just the guys that loved to hear Phil talk, though. Gale Claydon recalls the party in Dublin for Phil’s 21st birthday. “There were hundreds of birds there. Then after it was over he came to my room to tell me how lonely he was and could he come in and chat. It wasn’t until later I found out he’d already had four different females that night!”

“He was always trying to prove himself,” said guitarist Gary Moore, an old compadre of Lynott’s in Dublin, who would later pass through Lizzy’s ranks three times. “He had to be the guy who could outfight anyone, could pull more chicks, drink more. Dublin was a very small pond, but Phil was determined to be the biggest frog in it.”

In fact, Lynott was already looking beyond the Irish music scene, such that it was, towards England and America, swapping Van Morrison for The Band, while always under the spell of Hendrix.

“You have to remember, we were a bit behind the times when it came to the rock scene,” says original Lizzy guitarist Eric Bell. “The first time we saw a piece of hash wasn’t until about 1969. You’d have to meet someone straight off the boat from London, who’d sell you a quid deal.”

Bell (originally from Belfast, but living these days in West Cork) recalls an Irish music scene dominated by the show bands; big ballroom groups for people to dance to, not sit and look at.

“There were a few big Irish acts, like Them and Taste,” says Bell. Mainly, though, it was little groups with big dreams. “Groups that played a few originals but mainly did covers by The Beatles and the Stones, that sort of vibe.”

As teenagers, Lynott and Downey had played in one such outfit, the Black Eagles, mixing Elvis covers with Jim Reeves ballads. Now after a short but eventful spell in Skid Row, where bandleader and bassist Brush Shiels taught Lynott the basics of the instrument, as well as inspiring him to write songs, Phil was ready to form his own band.

Initially, this was called Orphanage, and featured local lads Pat Quigley on bass and Joe Staunton on guitar. Then they met Eric Bell, changed their name to Thin Lizzy – famously after a stoned Bell suggested it based on the Beano cartoon Tin Lizzie (“Try saying ‘thin’ with a Dublin accent and you’ll get it”) – and found their true musical identity.

Bell had been tripping when he’d introduced himself to Lynott and Downey at an Orphanage gig. Two years older than Lynott and bullish about his own musical prowess, Bell worshipped at the Truth-era shrine of Jeff Beck. “Eric when he first came into the band had this kind of leadership role that he adopted for himself,” recalls Downey. “But because Phil was writing the majority of the songs, it was always going to be Phil’s group.”

Always. Even after Lizzy acquired a manager in another Dublin adventure-seeker named Ted Carroll, it was always Lynott who called the shots. “Phil was the man with a plan,” chuckles Carroll today. “But they struggled for a long while before it began to work.”

There had been a one-off single, The Farmer, on EMI Ireland in July 1970 – Lynott’s go at sounding like The Band, even affecting a southern American twang – that had sold less than 300 copies. Things only got serious when Decca Records, one of the few major London labels with a presence in Dublin, offered them to a three-year deal.

“It meant moving to London, but we saw it all as the next step to our dream,” says Gale. “Of course it was still the days of ‘No Blacks, No Dogs, No Irish’, so it wasn’t easy.” Eventually, Carroll found them a one-room bedsit in West Hampstead. “Everywhere you looked there were notices stuck to the wall. ‘DO NOT TURN ON THE HOT TAP’, ‘DO NOT LEAVE THE LIGHTS ON’. Dreadful!”

Lynott spent most of the time travelling up and down the M1 in a transit van with Lizzy. Philomena paid for petrol and van repairs, stuffing a few quid in his pocket whenever the band were in Manchester, where she now ran a showbiz digs called The Biz – actually a small, scruffy hotel with no bar, named the Clifton Grange.

Lynott would be welcomed in The Biz as The Kid. Percy Gibbons, a six-foot black Canadian comedian, became a mentor to him. “Really intelligent, really well read,” says Gale. “He had Philip mesmerised because he just had so much knowledge.” Those were the days, she adds, when Lynott would enter a room and not want to be the centre of attention. “He was insecure, which he did his best to hide. But he had more chips on his shoulder than the Grand Canyon.”

Tempted by the thought they might have unearthed another Taste – the West Cork trio fronted by Rory Gallagher, whose second album On The Boards had reached the UK Top 20 that year – Decca put Lizzy into their in-house studios in Paddington in October 1970 and gave them two weeks to make an album.

Released in April 1971, Thin Lizzy was a blend of contemporary blues rock, traditional Celtic rhythms and Lynott’s own mystical poetry. It was the result, says Carroll, of Lynott’s immersion in the local Dublin folk scene, which included such figures as experimental folk-rockers Dr Strangely Strange and poet-warrior Peter Fallon.

All the big tracks were autobiographical: Look What The Wind Blew In mentions Gale; Clifton Grange Hotel namechecks Percy Gibbons. “It was really all about Phil’s life up till then,” says Downey.

Decca rushed the band back into the studio to record a follow-up, Shades Of A Blue Orphanage, named after Lynott’s previous band Orphanage and an earlier Bell outfit, Shades Of Blue. Released into the void in March 1972, this time the results were disappointing: a confusion of styles, half-baked ideas and stoned self-absorption.

The most impressive, if mish-mashed, song was the seven-minute opener, The Rise And Dear Demise Of The Funky Nomadic Tribes. The rest of the album wasn’t much more than the band desperately filling out Lynott’s sketchy templates for tracks he would rewrite much better in years to come.

It was a low point in Lizzy’s career, which nearly saw Lynott leave to join Deep Purple guitarist Ritchie Blackmore in a new outfit to be called Baby Face (named, adding insult to injury, after one of the more uptempo tracks on Lizzy’s second album).

“Ritchie turned up in the studio one day to jam,” says Downey, still incredulous. “I was asked to play drums to Phil and Ritchie jamming. Eric wasn’t asked to play. He had to sit in the control room and just watch. Me and Eric looked at each other like, ‘Well, that’s the end of the band then.’”

But Lynott was never going to take orders from Blackmore. “It lasted a week, then Phil just came back as if nothing had happened,” says Downey. “He wanted to be the leader of his own band, not the singer in someone else’s.”

Ironically, Lizzy would record an album of Deep Purple covers under the cringeworthy name of Funky Junction in order to pay off their increasingly hefty debts. “It was an embarrassment,” chuckles Downey. “But we were desperate for the cash. It got us out of a jam so we could carry on going as Thin Lizzy.”

With Decca reluctant to commission another Lizzy album, Carroll persuaded them instead to take a chance on a single. In an era when the music press was dividing new acts into two camps – album-oriented (read: cool) and single-oriented (uncool) – the decision to release a stand‑alone single was a last throw of the dice. “Phil had written this song for it which he saw as part-Hendrix, part commercial pop tune,” recalls Downey. “It was called Black Boys On The Corner.”

The first Lynott lyric to aggressively address his blackness, the sinisterly funky Black Boys On The Corner was also the first Lizzy track that gave a real glimpse of what the band would come to sound and feel like in the coming years.

All they needed was a B-side, but with Lynott preferring to keep his best songs for the next album, the band worked up a version of an old Irish folk ballad they had played for beer and dope money in their Dublin days: Whiskey In The Jar.

“It was an afterthought,” says Carroll. “But Eric worked up this fantastic electric guitar version, with that brilliant intro of his. The first time I heard it, I said: ‘This is a hit!’”

Decca agreed and switched the tracks around, making Whiskey… the A-side. Lynott was furious: he was sure Black Boys… was a hit. But Thin Lizzy were in no place to argue.

Whiskey In The Jar went to No.1 in Ireland, though it took a while to find its way onto British radio. But by March 1973, it was Top 10 in the UK and Lizzy were making their Top Of The Pops debut.

The band went from playing to 50 people a night to headlining halls in front of a thousand. But Lynott resolved that the next single would be much more representative of the real Thin Lizzy. Ironic, then, that the song in question, Randolph’s Tango, stood out like a sore thumb in the Lizzy repertoire. It was another storytelling vignette, this time replete with timbales, Spanish guitars and Lynott crooning like an ageing, over-refreshed roué.

“Phil loved Rod Stewart,” explains Downey. “He fancied doing something along the lines of Maggie May. I knew Randolph’s… wasn’t a hit as we were recording it, but I didn’t have the courage to say it to Phil. He was convinced it was an automatic hit. But it was a giant fucking flop.”

Still, Decca agreed to finance another album. “Phil had written some great songs for that album,” says Downey, “a great mixture of soft and heavy. Making it was the best experience we’d had till then. We were all very pleased with it.”

They had every right to be. Vagabonds Of The Western World, released in September 1973, was first and foremost a rock album and, as such, Lizzy’s new mission statement. From the shuffling opener, Mama Nature Said, with Lynott in full-on gang-leader mode, the feeling was immediately up. Suddenly all the hallmarks of the glory days to come were there. The ballsy rocker, simply titled The Rocker; the knowing-smile ballad (Little Girl In Bloom); the Celtic legend writ large (the title track).

It ended with another soon-to-be-signature Lynott motif: A Song For While I’m Away. Musically, with its tumbling melody and syrupy chorus, it could be one of those Jim Reeves ballads he’d sung back in the Black Eagles. But lyrically, this was Lynott looking to a time when the then fanciful words would come true: ‘Far away hills look greener still/But soon they’ll all slip away/It’s then I’ll be returning/And I’ll be coming home to stay…’

With great reviews in both Melody Maker and NME, and Radio One tastemakers like John Peel and Bob Harris falling over themselves to book the band for sessions, Vagabonds should have been a solid chart hit. Instead it flopped.

Lizzy lost their deal with Decca, and they lost Eric Bell. Despondent at the lack of recognition, drinking heavily and in love with an English girl who wanted to come on tour, despite the band’s strict ‘no girlfriends on the road’ policy, Bell finally quit on stage, in Belfast, of all places. On New Year’s Eve 1973 he hurled his guitar into the air mid-set and refused to come back on stage. “He broke the cardinal rule,” sighs Carroll, “leaving Phil and Brian in the shit, trying to carry on alone.”

Bell was contrite in the days that followed but Lynott had had enough. Eric was out. Gary Moore, another Belfast boy who’d made his bones playing with Lynott in the Skid Row days, was hastily drafted in. But when Moore bailed too, more interested in pursuing a solo career than trying to revive a band still trying to live down its novelty hit, Thin Lizzy appeared doomed.

What followed has gone down in Thin Lizzy folklore. The arrival of two previously unknown young guitarists by the name of Scott Gorham and Brian Robertson marked the beginning of a whole new chapter.

“Even after Eric went, Phil was never going to give up,” recalls Gale Claydon. “He had to make it. Even so, he’d be absolutely amazed to see how highly regarded he is even thirty years after his death. But he was never one of those people who were going to grow old. You just couldn’t see Phil with a bald spot and creaking limbs. He was a rock star. He’d made his mind up about that long before he became one. And he’s still a rock star now.”

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 219, in December 2015.