In the late spring of 1976, I flew to Los Angeles to write an article about Thin Lizzy for the NME.

I’d already met Lizzy several times and was thoroughly aware that although guitarists Scott Gorham and Brian Robertson, and drummer Brian Downey, played significant roles in the group, it was Phil Lynott who led the band.

They were in town to play a show on June 2 at the Santa Monica Civic, not topping the bill but supporting Journey. Since the booking, their single The Boys Are Back In Town had surged up the US charts, pulling the Jailbreak album behind it.

As we sat by the pool on the roof of the Hyatt House hotel, we both knew this was a pivotal moment. The cavalry, in the form of the hit single and album, had arrived just in time, heading off the group’s creditors at the pass and saving them from breaking up. Now, the only way was up.

Like a reflection of this, Lynott seemed chipper that day. Perched on the edge of a sunbed that had been pulled into the shade of a parasol, his bare feet stuck incongruously out from the bottom of his black leather trousers, which was somewhat inappropriate wear considering the baking heat. His top half was encased in a black cowboy shirt, its silver press-stud buttons snapping the sleeves firmly shut around his wrists, as though he was making a point about his attitude to life.

But as we talked, I couldn’t help noticing that he looked quite exhausted. Despite his natural bravado, the demands of newfound success were having an effect on him.

“I mean, okay, the band’s breaking,” he told me in that rich Dublin brogue. “It’s not that important that we break as fast as we’re breaking. It’s never been that important to me. It’s the quality of the breaking. If we break with quality we’ll last like all them bands that are me heroes. Like The Who. That band’s great. It’s got integrity and that’s why it works. Pete Townshend never lost contact with his audience and he didn’t go through too many mind fook-ups.”

I’ve noticed that you seem to believe almost passionately in a kind of total contact with Thin Lizzy’s fans. And you seem to certainly believe in songs, as opposed to just getting up there and creating a series of sounds.

Yeah [nodding]. Well, I was a singer, right, and the 60s proved that melodies played in the rock idiom… That whole weird thing rock went through when the arrangements dominated – ELP, Jethro Tull and 10⁄4 time – was very harmful to rock because although there are a lot of good musicians, musicianship and melody don’t always have to be the same thing. And there’s a lot of false focus. The very harmful stage of the whole thing was when the bands just got up and just let it float. Put screens and films on and hoped the audiences were tripping and that they’d get off on it.

Of course, much of that pretension came from such acts considering themselves as artists. But you also certainly regard yourself as an artist, and not just in the field of music. For example, you’ve sold 10,000 copies in the UK of your book of poetry, Songs For While I’m Away.

I’m incredibly proud of that. I’m more proud of that than, say, I was when the record got into the charts. A budding poet, eh? There’s a guy here in LA who’s written how I’m Bruce Springsteen. Now I have to spend half me interviews saying “I’m not fooking Bruce Springsteen” and that I appreciate him but I don’t try to imitate him. I take it as a compliment when we’re compared, but I take it as an insult when it’s said I imitate him. This guy ’ere in LA worded it in such a way that all of a sudden I’m on the defensive. It’s a freaky one, the power of the pen.

So is the power of being up onstage…

Oh, yeah. [Momentarily distracted as he wheels around to follow a passing bikini bottom] That’s the nice thing about being a live act. I can get the audience, but it’s for the moment. It’s like, “Can I do it tonight?” And you can see when people like you. But on record – and with the pen – it’s almost for all time. Really a lot more thought has to go into it.

At this point, Chris O’Donnell, Thin Lizzy’s co-manager, wandered over and handed Phil a set of photo contact sheets the band had taken at Disneyland the previous day. The frontman flicked through them, largely satisfied.

“I only want shots where I look ’andsome,” he said, smiling with a measure of irony. “And some of these are very funky. I love shots where the band look grassed. Knowharramean? And I think the girls do, too.”

Thin Lizzy seem to be doing very well with girls now. But you still remember the bad old days, though, Phil? Remember being looked on as a token loser band?

Yeah.

You were actually conscious of that, then?

I was conscious that the media saw that we didn’t follow up Whiskey In The Jar. And we didn’t in terms of record sales. The only place we seemed to be happening was on the street. But, you know, that’s Thin Lizzy summed up for you. Like an album and three singles after Whiskey…, man, you’d get people mentioning Whiskey… in interviews – and I’d go “Oh Jeezuz”. That was how far behind the press got on the band. They really lost contact. They were all going on about ‘the Irish traditional thing’. Bad photographs went out. We were generally misrepresented. You know, all the things that I’m worrying about now happened to us the wrong way. And that’s where we got the loser tag. And then when we broke up – well, not many bands break up three times. [Laughs] And still come out on top.

Which can’t be just down to your ego?

It’s also down to our drummer Brian Downey. Me and Brian have known one another since we were kids. But I’m the mouthpiece of the band. You take a band that’s made up of arms, legs, bodies… I happen to be the piece that talks. And does all that area of it, you know? I’m also very easy to recognise; the darkie in the middle jumping around with the guitar, you know. Dat boy’s got riddim! Knowharramean?

The Santa Monica Civic show was a real triumph. Lizzy were introduced over the tannoy as “the next supergroup”. But just over a week later, the rest of the tour was cancelled and Phil flew back to London, where he spent two weeks in an isolation hospital: he had been diagnosed with hepatitis.

Later he admitted to me that during the LA stint he had shared a needle with a girl, catching the disease. Though he never revealed what drug he had been injecting, I assumed it was heroin. While it would later haunt his life, at the time I felt it was simply a one-off.

While he was in hospital recovering, Phil wrote much of Johnny The Fox, the follow-up to Jailbreak. Despite the success of the single Don’t Believe A Word, released in October 1976, just six months after Jailbreak, the album was widely felt to have fallen short of its predecessor.

Johnny The Fox was followed almost a year later by Thin Lizzy’s eighth album, Bad Reputation, a tougher, more substantial record. It was launched with a one-day festival at Dalymount Park in Phil’s home town of Dublin. Also on the bill were Graham Parker, Fairport Convention, the Boomtown Rats and the Radiators From Space.

The day before the Dalymount Park show, I found myself with Phil in the centre of Dublin, in Bailey’s Bar, where the 1916 Easter Rising had been planned. It was the singer’s 28th birthday, and he was downing some celebratory pints before moving on to some serious partying at Castletown House in County Kildare, home of Desmond Guinness, of the Guinness dynasty. He gazed into his glass of beer as he extemporised on his approach to his existence as a rock’n’roller.

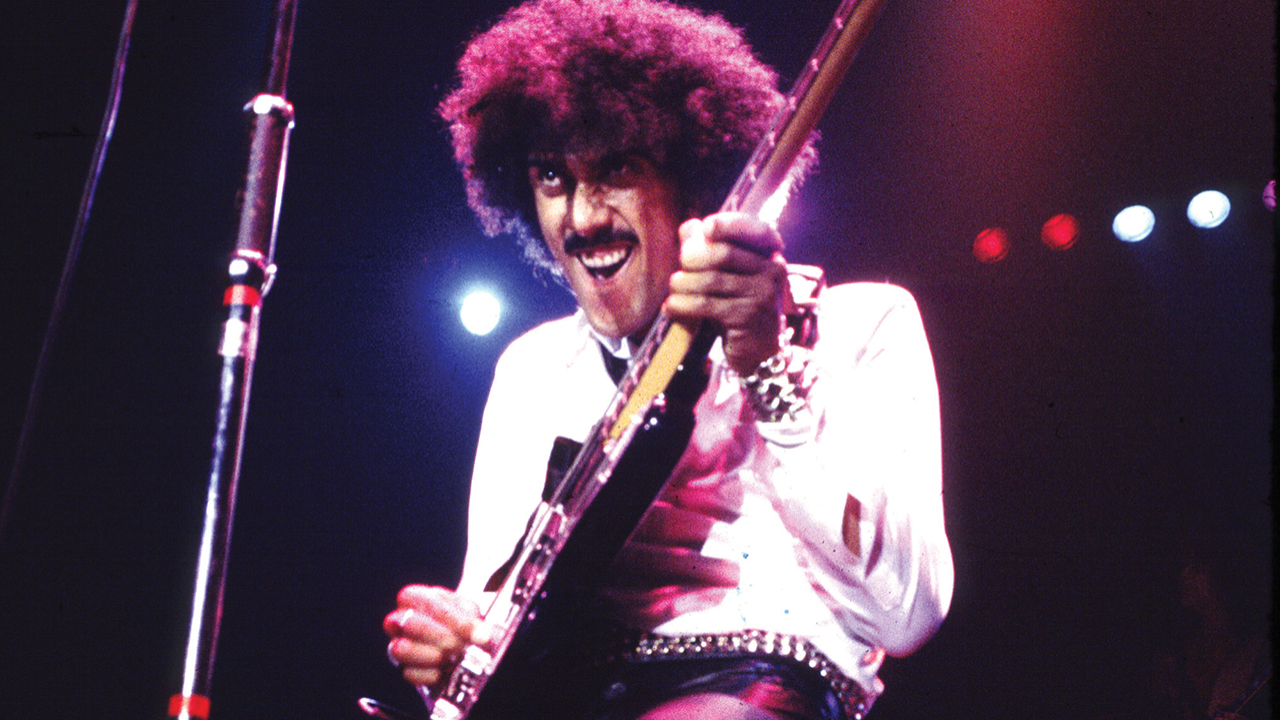

“Sometimes I get up there onstage and I go completely berserk – I’m often completely off me fookin’ head,” he said. “And it’s got sweet fook-all to do with drugs, man. It’s just that I can get as heavily into what I’m doing as when I used to be a kid playing cowboys, when you’d be completely wrapped up in killing millions of Indians and just living this whole trip out: hiding behind rocks and trees and sneaking off to imaginary places. Anybody can be anybody in rock’n’roll. It allows for all these people to exist within it and live out their fantasies. I mean, I certainly do.”

He was also looking forward to coming back to the UK in November, after a return visit to the US. “This whole image thing that’s going down between new wave and boring old farts will be sorted out and we’ll be able to just play.”

Do you feel at all professionally intimidated by the rise of punk and the new wave?

Everything they’re singing about I actually do: I do what I want to do. I never wanted to be like anybody else. I don’t give a fook about good, bad or indifferent music – I just like what I like. I don’t care if we lose whatever title or success we have. Because it’s only something the kids give you. And if they want to take it away from you, it’s their God-given right, man. I’ve no God‑given right to be up there saying I’m the people’s choice. I mean, I’m glad for the couple of years that I’ve had. And if it’s ever all over, it’s all over. But [laughing determinedly] I’ll be the last to give in. Knowharramean?

[Glancing around, distracted] Fook, man, they’re the prettiest colleens in the world in this town. The only trouble is I can’t get away with giving ’em the blarney like I can everywhere else. I have to adopt the more subtle approach: “DO YOU DO THE GIG?”

Have you always been living out this Johnny Cool, quasi-gigolo persona?

I was with a girl for a long time and we split up about three years ago. I just went totally insane after being so faithful and so loving for so long. That’s why I’m the easiest lay in town. Now it’s two drinks and “Take me home, baby.”

Are you playing at being a rock star? I’ve certainly heard women accuse you of being sexist.

I get this big tag of being sexist. [Smiling, almost gleefully] But you know I’m not. I think chicks are pretty fookin’ together, pretty okay. In general chicks are smart. But boys talk different behind chicks’ backs. No matter what anyone says. If the lads are together then it’s different talk to if there’s a chick in the company. And because I actually write songs about these situations – like Don’t Believe A Word or_ The Boys Are Back In Town_ or The Rocker – where it’s real lads’ talk, I get a lot of chicks saying, “That guy. Who does he think he is? Thinking chicks are dumb?” Which is not the point that I’m trying to put across at all. I’m just trying to show [pursing his lips] the reeeee-alllll truth of what’s going on in those situations. There are times when I’ve gone with chicks who’ve been insisting to me that I am not black! Well, baby, I am certainly not white. There is no way I can go grooving around South Africa.

Are there many other black guys in Dublin, Phil?

Oh, there’s a few. There’s, uhh… there’s Dave Murphy [pointing out a black guy with dreadlocks at the bar, who waves a greeting before returning to his pint of Guinness]. But, you know, people in Ireland aren’t that bothered by what colour your skin is. If you’ve got big ears, they’ll say, “There’s the geezer that has big ears.” Or they’ll talk about you as the feller with the funny hat and the leather jacket. And like I’m black so they’ll just go, “There goes the dark guy.” Now the hardest time I ever had being black was when I went to England for the first time and tried to find a pad. Being Irish is bad enough without being black as well.

I’m very proud of being a brother. Don’t get me wrong. But I think that there are a lot of people like Stevie Wonder who’re more apt than me to put it across. My cause is more the half-caste cause. You know, a lot of people are really delicate with the questions: “It must be really difficult being a half-caste.” But to me I am normal. Everybody else is different. I know it’s an existentialist point of view: that I am the centre of the world.

Well, that can be quite logical. You can, if you so wish, see all viewpoints, be the fulcrum around which all the nonsense can move. And keep laughing.

Right. Right. Well, that’s your French writers for you. [Mimicking a stage Irish voice] They put me perspective roight when I was a young la-a-ad. I was into that for a long time. Figuring I was number one. And if I die the world ends. I was into Sartre and his pals for a long, long time. I believed what they wrote was correct. Now I’m not so sure.

Why?

Because one day I looked at history – history freaks me, you know. And for some reason I happened to think – and maybe it’s that Catholic base that gets you every time – that there must be hope; that there must be somebody up there looking after the side of good. It’s too easy for evil to win, and good has won out nearly every fookin’ time.

I was born Catholic, reared Catholic, churched, everything. But I went to England and saw that other people didn’t go to Mass and I didn’t go to Mass. I started seeing that it was easy to be with the girls. And I just lapsed. But every so often I’ll think I’m going to crash in a plane or something and I’ll find myself going, “Jesus, Mary and Joseph, don’t scare me like that, Motherofgod, fer fook’s sake.” All this stuff that’s been beaten into you just comes out. It just catches you when you’re a kid. So now I look on it as a basic set of ground rules that are really important. They’re a great set of rules to look at. I can say, “I’m breaking this rule here.” But at least I have a set of rules to work off.

Listen, you’re staying at the Gresham [hotel], aren’t you? You’ll see little kids begging outside the Gresham. You will, honestly. And then you’ll go inside and you’ll see hordes of nuns and priests drinking brandy. And it disgusts me. But as much as I’m disgusted by the way it’s run, the basic ideals and the fundamental rules that they’ve taught are very sound.

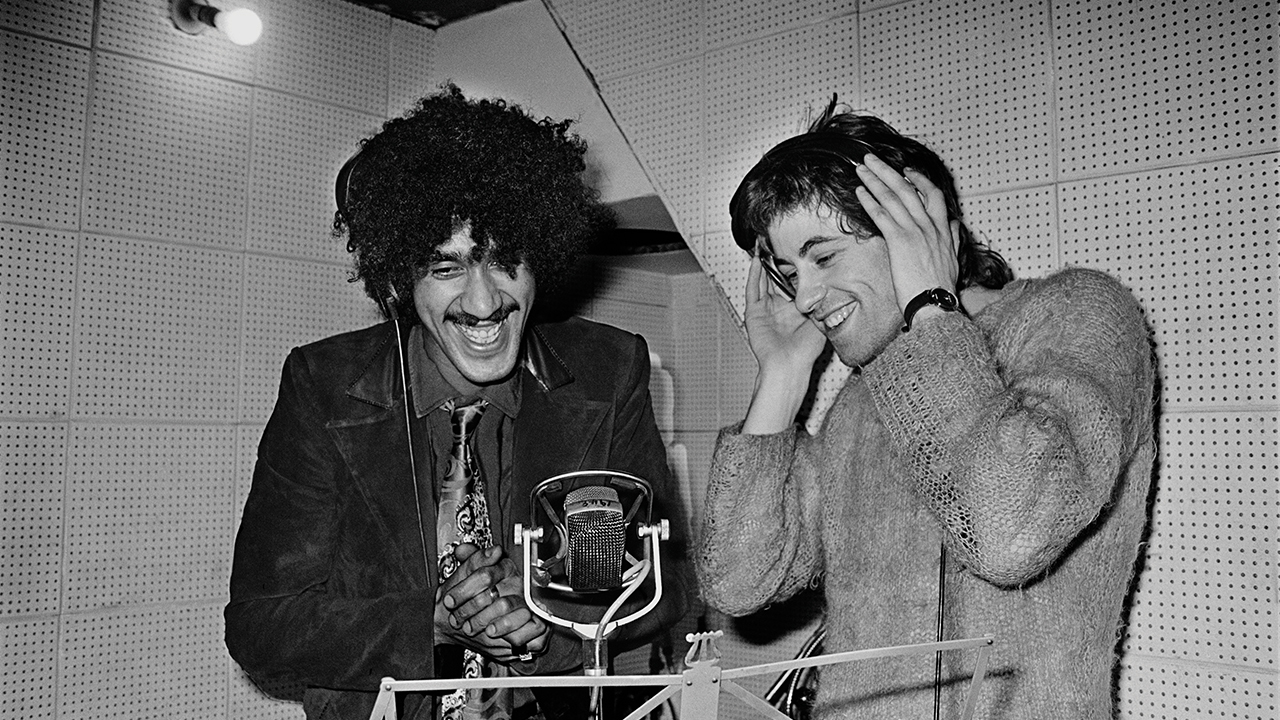

As we had been talking, Bailey’s Bar had become mercilessly packed with Saturday night drinkers. Across the room, Bob Geldof was pinned in against a table by fans, apparently proffering the kind of semi-sermon for which in time he would become legendary. Phil glanced at him, gave me a knowing grin, and stood up, hitching up his black leather trousers.

“Hang on a minute. I’m dying for a piss.”

Two days later Phil was stretched out on the king-size bed in his hotel room on the outskirts of Dublin, taking occasional sips from a pint of bitter. He kept one eye on the TV set: it was half-time in the Gaelic football semi-finals and Dublin were trailing behind Kerry 13-12.

The previous day at Dalymount Park, Thin Lizzy had unveiled several songs from Bad Reputation to some 25,000 people. As they returned to the stage for an encore of The Rocker, I couldn’t help notice from my position in the stage-front VIP pit that Phil had a clump of white powder lodged in his moustache beneath his right nostril. It would have been simple for him to wipe away this cocaine residue, and I couldn’t help wondering if this was deliberate, a signifier of his outlaw cool.

Sprawled on the bed 24 hours later, he seemed to be in a state of creative comedown, quiet and reflective. Instead of asking him about the new album I had some questions about the previous one. Scott Gorham, for one, told me that he thought Johnny The Fox was a little weak in comparison with Jailbreak.

“Well, I don’t agree at all,” came the reply. “I think Scott’s missing the point. Especially in the perceptions of the lyrics, I think it was a far more mature album than anything Lizzy had previously recorded. I wrote most of it while I was still in the early stages of recovering from hepatitis. But in retrospect, I can see that I was very sick and, therefore, it is a lot milder than Lizzy generally are.”

How did the hepatitis affect your view of life?

You know, at first I just thought I had a fookin’ dose. But I was unable to drink for six months. Standing in bars watching other people getting drunk was a revelationary experience. Being sober for so long gives you a whole head turnaround. So I went through a few changes. For the better, I hope. It was definitely me body saying, “Enough.”

I’d been living such a wild life up until then. And for the three weeks I was in hospital, me mother just laid into me with everything she’s wanted to say to me for the last year. “And you don’t look after your teeth either.” I was just lying there. Couldn’t even defend meself.

And it does hit you after a while that the night life is maybe a bit of a wild life. You’re chasing the wrong things. That was the idea behind Fool’s Gold. I wouldn’t have written either that or Massacre without having been ill. You caught me on a bit of that tour: I was going it. I was going ten to the dozen.

Perhaps you were trying to live the life of a Dylan Thomas-like hard-drinking, carousing poet. After all, you’ve just had your second book of poetry, Philip Lynott, published…

Poet? Seems like a whole career. It’s hard enough trying to say I’m a musician. I’d just prefer it to be musician. I work in lyrics, and music has lyrics. But poetry in that, yes, it means a lot to me. I was actually writing down what I thought and believed in at these periods in me life.

Why do you write lyrics and/or songs?

The main thing that pushes me to write a song is to share my personal experiences. Plus the sheer ego of thinking my life is so important it should be shared. But I also put it down for meself. It helps me really get a perception of phases I was going through. That way both the books and the albums have been a great source, a great guide, for me to see how I’m developing as a person and if I’m actually achieving the things that I originally set out to do.

Basically, though, it’s to share an experience. I could preach. Bob Dylan did it a lot in the old days and a lot of the new wave bands are doing it a lot now. They’re preaching really strong stuff. But I can only do that when I’m right. And I have to go into it a little bit deeper than just a catchy line. In a way I ran into that with Fighting. It was preaching anarchy, you know. And whereas Johnny [Rotten] and his boys may be into anarchy, I’m not. I’m extreme, but I can’t take anarchy. Maybe there’s a reference to Ireland in that.

How do you feel Thin Lizzy are doing at the moment?

[Almost bashfully] I’m completely zapped at how much we’re accepted as a major band.

But you’re at a crossroads, aren’t you? You can subtly dilute what you’re doing and your approach to it and go for mega-stardom. Or you can follow your chosen art to its ultimate conclusion, to perhaps justify to yourself the ravaging and self‑abuse that is beginning to appear more and more as the hallmark of rock genius.

When I wrote Warriors on the Jailbreak album, which is a song about heavy drug taking, the only way I could give any sense of heavy drug takers was by describing them as warriors; that they actually go out and do it.

People like Hendrix and Duane Allman were perfectly aware of the position they were getting into. They weren’t slowly being hooked. It was a conscious decision: to go out and take the thing as far as it can go. To the limit. And some of them really did. Tell us what it’s like, man.

But Warriors also seems autobiographical. In the song I have the suspicion you see yourself as that warrior figure, cutting your way through life. Will you take it to that extreme?

I don’t know. We’ve succeeded in doing what we want to do. I’ve put all me energies into Bad Reputation, the new album. Now we’ve achieved our goals we have to find new ones. And if those goals mean taking it further to the extreme, I won’t be able to tell you until we get back from America. [Laughing] But I’d do it – and I know I will do it – whether I was successful or not.

Of course, Phil Lynott did take it to further extremes. He loved the hedonistic lifestyle, yet as Bob Geldof had pointed out, he also believed it to be part of the job. He revealed his own contradictory feelings on the subject on Got To Give It Up, from 1979’s_ Black Rose: ‘I’ve been messing with the heavy stuff, for a time I couldn’t get enough/But I’m waking up and it’s wearing off, junk don’t take you far.’_

Living the fool’s gold of a rock’n’roll lifestyle as he perceived it was what brought about the end of Phil Lynott on January 4, 1986.

I loved the guy: he was hilariously funny, really bright and shrewd. At times he was an inspirational and supportive figure to me.

Dear me. What a tragedy.