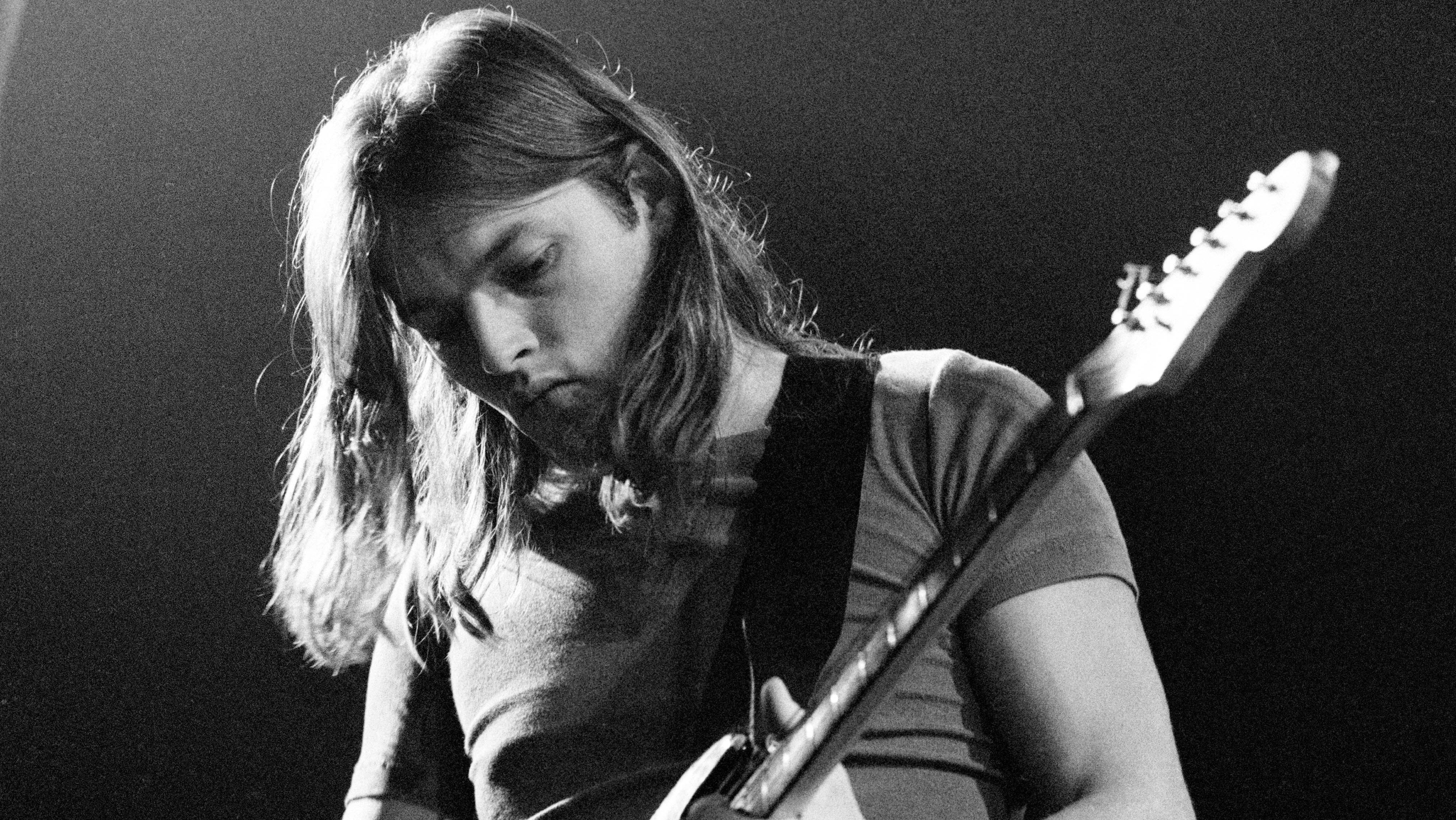

David Gilmour described Pink Floyd’s 1970 album Atom Heart Mother as “a load of rubbish... we were scraping the barrel a bit at that period.” His bandmate, Roger Waters, was no less harsh, later stating that if anyone was foolish enough to ask him to perform it now, he would tell them unequivocally: “You must be fucking joking.”

And yet the album that Pink Floyd’s two main protagonists at the time were so quick to dismiss was a landmark on many levels: the first British ‘rock’ album to feature one track covering an entire side of vinyl; the first to appear without any indication on the sleeve of who the group was or what the album was called, or indeed any information whatsoever; the first Floyd album to feature an outside writer (Ron Geesin, who co-wrote the monumental 23-minute title track); the first Floyd album to be specially mixed for four-channel quadraphonic sound as well as conventional two-channel stereo; and, despite all this, the first Floyd album to go to No.1 in the UK chart.

Atom Heart Mother marked the moment that Pink Floyd came in from the cold of their post-Barrett malaise and found the way forward, towards everything we now remember them best for. Not simple pop-psychedelia, nor mere prog showmanship, but a clearly thought-out, if occasionally wavering, attempt at something that could neither be categorised as rock, nor classical, nor indeed anything else outside of what it is: its own faltering, frustrating, enticing, fundamentally flawed yet gloriously individualistic musical form. And while side two of the album comprised three five-minute tracks, each written by one member, culminating in a final ‘suite’ of sound effects largely concocted by Nick Mason, it was the title track – co-written with the aforementioned Scottish avant-garde musician and composer Ron Geesin – that finally cemented Floyd’s burgeoning reputation as creators of both art and music.

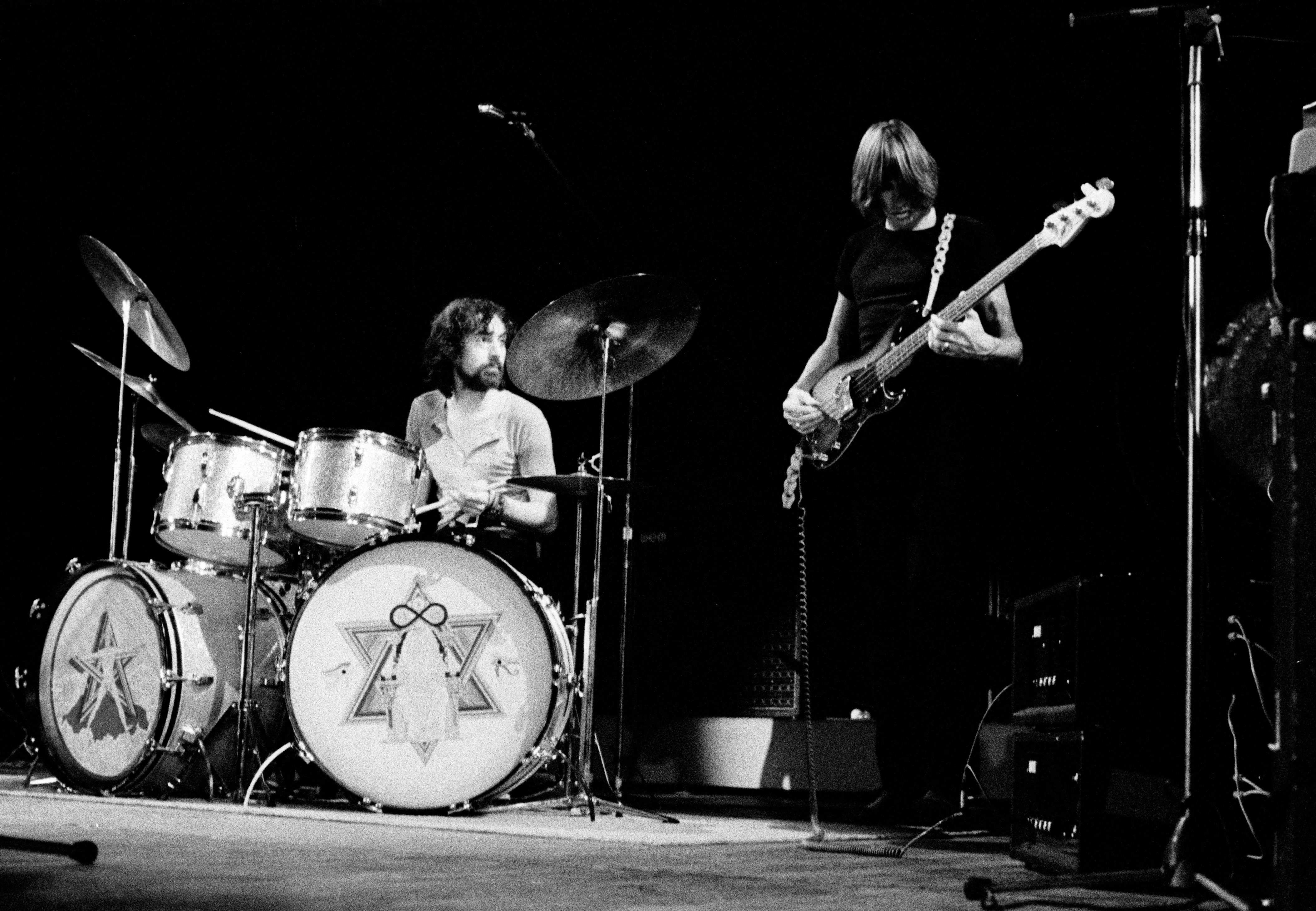

“It has a life of its own, that’s for sure, outside of what any of us thinks of it,” Ron Geesin says now. Despite having first met drummer Nick Mason in 1968, Geesin was so far off the rock grid that he’d never heard of Pink Floyd. “I was too busy with my own self-conjured endeavours.” These included a one-man show he describes now as “a Dadaistic eruption”, as well as his work with tape recorders and electronics on a variety of art projects for radio, film, TV and “my own totally uncategorisable recordings.”

But it was Geesin’s relationship with Roger Waters that would lead to him working on Atom Heart Mother. “We were both a couple of… well, I shouldn’t say ‘nutters’, cos we weren’t nutters,” Geesin says. “We had lots of enthusiastic and alternative thoughts. We hit it off and started seeing more of each other, dinner parties and so forth. Then we started playing golf. It was a kind of therapy.”

Geesin had invited Waters to collaborate with him on his soundtrack for filmmaker Roy Battersby’s extraordinary documentary The Body (cue a bewildering series of burps, farts, sighs and heavy breathing). When Pink Floyd found themselves foundering over their next album, Waters invited Geesin to attempt a musical rescue mission.

They had demoed five untitled instrumentals, strung together as one continuous piece titled The Amazing Pudding. But the band were now off on tour, and clueless as to what to do next on the record.

“They had only made a backing track, and they genuinely didn’t know what to do with it,” says Geesin. “But they needed to do something because EMI were pushing them. And their egos were pushing them as well. But they were knackered, from all the touring. It’s a wonder they were still standing up.”

Geesin worked out of his Notting Hill basement through the sweltering summer of 1970, often stripped to his underwear. “Since none of them could read or write music, I was left to get on with it,” he says. “And I was glad. Rick and Nick came in right towards the end, but only to have a bit of a listen. Just a few notes on the first themed section and the first few bars of the choir, and how that might start.”

By then, Geesin had retitled the piece Epic. It was this version that the band debuted at the Bath Festival in June 1970. When John Peel requested the title ahead of a Radio 1 broadcast a month later, Geesin drew Waters’s attention to a story in the Evening Standard about a woman being fitted with a nuclear-powered pacemaker, headed: ‘ATOM HEART MOTHER NAMED’. Waters seized on it. Not for the title of just the Floyd’s most ambitious piece yet, but of the entire album.

“Nobody knew what it meant, it just sounded right,” says Geesin now. They also kept his suggestion for naming the opening section Father’s Shout, after the American jazz pianist Earl ‘Fatha’ Hines. (Other section titles, such as Breast Milky and Funky Dung, were ‘inspired’ by the sleeve artwork.) Geesin doesn’t recall getting any further feedback about the work he’d done, other than being called to Abbey Road studios to assist in the actual recording. The only trouble he encountered came from the orchestra.

“It was nearly a disaster, because the brass were hard session musicians and I was not used to working like that. EMI had their own guys they used and they were not helpful – the worst kind of jobsworths. And because I wasn’t trained like they were they thought: ‘We’ll have this bastard!’. And they very nearly did.” Fortunately, the choirmaster hired for the session, John Alldis, arrived a day early and offered to intervene. “It was just as well. I had my arm pulled back ready to hit the horn player.”

A less unnerving yet historically more interesting moment occurred when Syd Barrett – then recording his second solo album in another studio at Abbey Road, with Gilmour producing – suddenly appeared.

- The 10 Roger Waters Tracks Every Pink Floyd Fan Should Own

- Kettles and chaos: the crazy story of Pink Floyd's lost album, Household Objects

- Five Classic Moments From Pink Floyd's Wish You Were Here

- The 10 heaviest Pink Floyd songs

“He turned up during a break,” Geesin recalls. “He breezed in, in a long coat, spun round a couple of times, and disappeared. Someone said: ‘This is Syd Barrett’. I didn’t even know who he was. I had a vague notion that he had been a member of the group and had left, but that was all. There was no idea of someone with talent or who had done a lot of work or anything, it was just: there he was and there he wasn’t.”

Pink Floyd nearly joined their former leader in career suicide when the powers that be at EMI heard the finished Atom Heart Mother album. One executive gazing puzzled at the Hipgnosis-designed sleeve could only offer: “Friesians, aren’t they?”. In fact designer Storm Thorgerson – inspired by Andy Warhol’s earlier ‘cow wallpaper’ drove out to a field in Potter’s Bar and “photographed the first cow I saw.” Nevertheless, when it was released in October 1970, Atom Heart Mother went straight to No.1 in the UK.

Geesin insists he wasn’t aware of the fact until someone asked him how he felt about it. “I thought, oh, that’s amusing,” he says.

He does, however, recall the mixed reviews the album received. “I’ve still got the little cuttings in my archive. But side two wasn’t anything to do with me so I didn’t feel particularly strongly. With 42 years of hindsight, though, I’d say it was an interesting collaboration of disparate forces that happened to make something bigger than any of the individual parts.”

Film director Stanley Kubrick wanted the title track for A Clockwork Orange, but talks broke down when the inscrutable Kubrick had a face-off with the intractable Waters over which section of the film it would actually be used in. And despite their later backtracking, Pink Floyd initially went to great pains to perform the title piece of their new album live, dragging both choir and brass section out on tour with them. When that proved impractical, they paired the piece down to 15 minutes by omitting the ‘collage’ sections, and were still regularly performing it up to 1972, when Dark Side Of The Moon replaced it as their centrepiece.

In June 2008, when Geesin performed Atom Heart Mother at the Chelsea Festival in London with Italian tribute band Mun Floyd, Gilmour joined in, extending the performance to more than 30 minutes. “I only came back from France three weeks ago, where we did it,” he enthuses. “The brass was the best in Europe. It was proper, marvellous, really fantastic! And so it goes on…”

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #190.