Pink Floyd’s Live At Pompeii: the saga of rock’s most epic home movie

In 1972, Pink Floyd staged their most ambitious gig yet – in the ruins of Pompeii. But that was just the start of the drama…

“It’s just us playing a load of tunes in the amphitheatre with some rather Top Of The Pops-ish shots of us walking around the top of Vesuvius and things like that. I think Pink Floyd freaks would enjoy it. I liked it because it’s just a big home movie.”

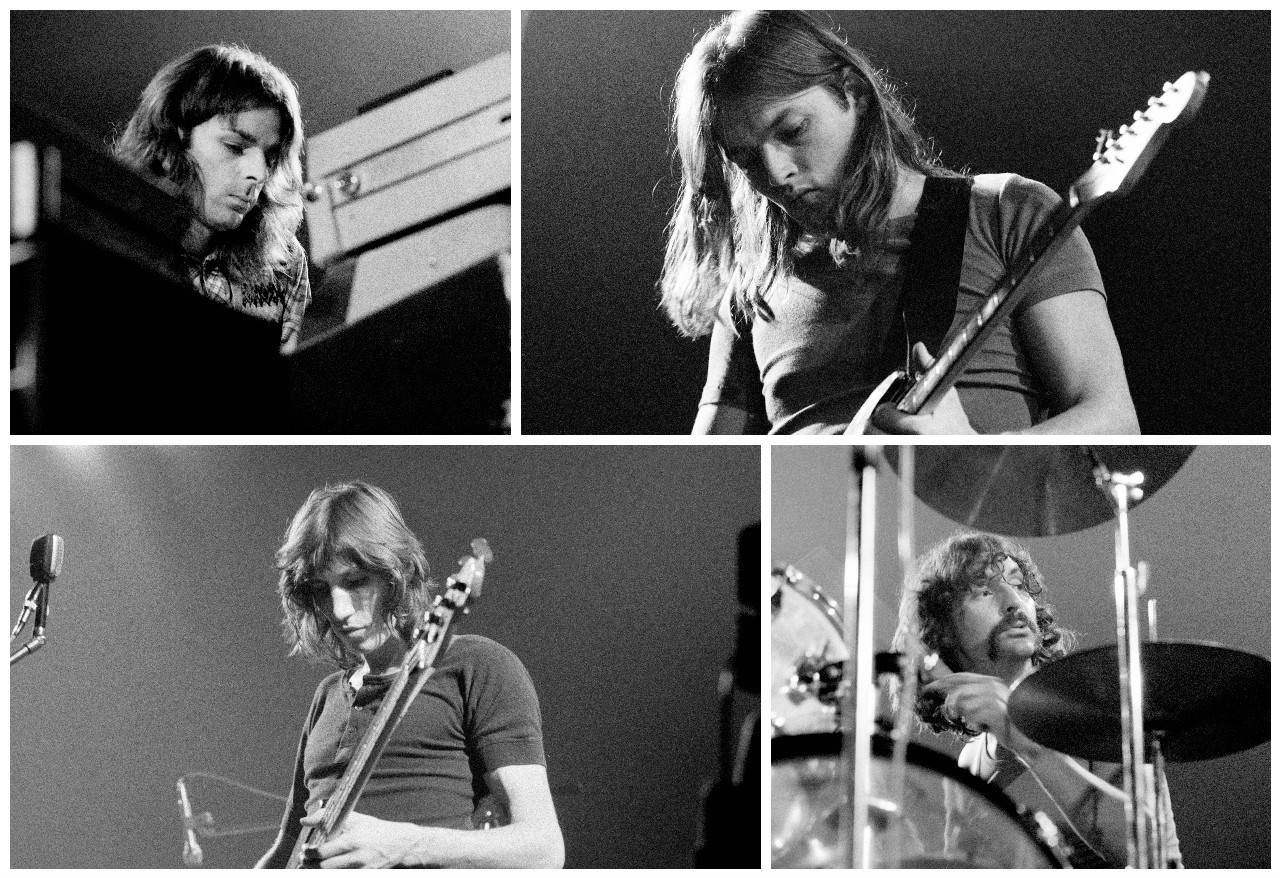

The movie Pink Floyd Live At Pompeii got a rare thumbs-up from Roger Waters when it was premiered in September 1972. The setting, the atmosphere and the performance were echoed by the long, sweeping tracking shots that accompanied the music and some gripping visual images – notably of Waters thrashing a gong, set against a vivid setting sun.

Nick Mason also has fond memories of making the film: “It turned out to be a surprisingly good attempt to film our live set. We had been approached by the director Adrian Maben, whose idea was to shoot us playing in the empty amphitheatre beneath Vesuvius,” he recalls. “At a time when other rock films were either straight concert footage or attempts to copy [The Beatles’] A Hard Day’s Night, the idea was appealing.

“The elements that seemed to make it work – none of which we really thought about during the filming – were the decision to perform live instead of miming, and the rather gritty environment created by the heat and the wind.”

Live At Pompeii caught Pink Floyd at a particularly propitious moment. Shot just before their album Meddle was released at the end of 1971, it highlights the best of the band in the five-year period between Syd Barrett’s departure in 1968 and the arrival of The Dark Side Of The Moon in 1973.

After its premiere at the Edinburgh Film Festival, the film disappeared for two years, and by the time it re-emerged the world seemed to be living in the huge shadow cast by Dark Side…. The irony was that, in the meantime, director Adrian Maben had added footage of the band recording The Dark Side Of The Moon, but it was not enough to save the movie.

Maben, a British-born director living in Paris, had approached the band early in 1971. “The original idea was to make a film using modern paintings by de Chirico, Delvaux, Magritte or Christo as some kind of surrealistic décor,” he told the Pink Floyd webzine Brain Damage. “I naively thought it would be possible to combine good art with Pink Floyd music. I had a meeting with [Floyd’s] manager Steve O’Rourke and [guitarist] David Gilmour where I cautiously produced a few books and some photos of paintings. They were very polite and totally unconvinced. We agreed to talk about it again at a later date; in other words: ‘Forget the whole idea.’”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Having established contact with Pink Floyd, Maben was not going to let go that easily. That summer he was on holiday with his girlfriend, travelling through Italy, when they visited the Roman ruins of Pompeii, a town that had been literally buried alive by the cataclysmic eruption of the (still active) volcano of Vesuvius in 79AD.

That evening Maben discovered that he had lost his passport – the first of several significant items to go missing during the saga of the film – and went back to the ruins to look for it in the ancient amphitheatre where he’d eaten a sandwich earlier.

“It was strange, a huge, empty amphitheatre with some echoing insect sounds, and the disappearing light which meant that you could scarcely see the other side of this huge structure built more than 2,000 years ago,” he recalls. I knew by instinct that this was the place for the film.”

- The Eagles albums ranked from worst to best

- The 10 heaviest Pink Floyd songs

- Traveling Wilburys share Behind-the-scenes videos

- How the Lifehouse album was almost the death of The Who

The more Maben thought about it, the more the idea contrasted with the prevailing trend of films like The Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night and Help, Dylan’s Don’t Look Back, The Rolling Stones’ Gimme Shelter and festival documentary Woodstock.

“What was the point of just doing another concert film with the Floyd?” he says. “It somehow all came together that evening in the ancient city: film the empty amphitheatre, resurrect the spirit of Pompeii with sound and colour, imagine that ghosts of the past could somehow return…”

Maben’s idea appealed to the band, and a deal was struck. But Maben still needed to get permission to film the band in Pompeii itself. “The authorities were suspicious of letting a rock group play in the amphitheatre,” Maben says, “but I was lucky enough to find a professor at the University of Naples who had connections and was also a Pink Floyd fan. After an exchange of letters and payment of a fee, we were given permission to film for six days at the beginning of October.”

Three of those six days were spent trying to get the power supply working. “I was going crazy trying to get the problem fixed, while the Floyd were hanging around doing nothing,” Maben recalls. “On the third day of despair [Floyd sound engineer] Peter Watts suggested we fly in an Englishman, someone he said was an electrical wizard who could fix the problem. We were just about to ring him when suddenly the current was switched on. A long cable now stretched from the amphitheatre to the local church.”

The band had arrived from England along with all their equipment because, as Nick Mason says, they insisted on playing live. “The quality of the sound was fantastic,” says Maben. “The stone walls of the amphitheatre were better than a recording studio.”

With the Meddle album about to be released, Pink Floyd naturally wanted to showcase the new material. They split the album’s 24-minute Echoes into two parts that book-ended the film, along with One Of These Days. Maben remembers listening to an advance copy of the album on a “small, scratchy, plastic gramophone” in his hotel room, plotting the camera angles and tracking shots overnight.

“I politely requested Saucerful Of Secrets because I thought it would look great with Roger’s spectacular beating of the gong and David’s controlled torture of the guitar,” says Maben. Both songs were duly delivered.

Nick Mason remembers that even though it was October “it was still quite hot, shirts-off weather. It was hard work with no nights out sampling the local cuisine and wine list, but the atmosphere was enjoyable, with everyone getting on with their jobs. At the end of the amphitheatre sessions we headed off up the mountain to shoot some cut-ins among the steam of the hot springs, and had a brief chance to explore Pompeii itself.”

The band left immediately after the final day’s shoot, leaving Maben with the first of many problems that would bedevil the movie. “The producer wasn’t able to pay the hotel bill. No more cash! I was asked to remain in the hotel and wait for the money. As I sat alone in the Grand Hotel and drank too much wine, I mused on what to do next. Above all there was the nagging question: would the band agree to play later and fill in the holes that I had left in the shoot?”

They would. Early in 1972 Pink Floyd went to Paris and performed two more songs in the studio: Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun and Careful With That Axe, Eugene.

But now a more serious problem had arisen: several cans of film shot for the movie had gone missing somewhere between Pompeii and Paris. They included some camera shots focusing on Roger Waters and Rick Wright. Without them, even with judicious editing some songs in the final movie virtually turned into a Nick Mason extravaganza. It’s particularly apparent when the drummer is thrashing away on One Of These Days as an unseen Waters delivers the song’s only lyric: ‘One of these days I’m going to cut you into little pieces.’

The film’s premiere at the 1972 Edinburgh Film Festival should have been the trigger for a distribution deal. But negotiations dragged on and before long the film was overtaken by events – namely The Dark Side Of The Moon. The film’s commercial prospects were now hampered by the lack of any material from the new album, even before Dark Side… had acquired legendary status.

Once again Maben went back to the group – probably on bended knee. The outcome was a third filming session, at Abbey Road, ostensibly showing the band at work in the studio working on The Dark Side Of The Moon. In fact the album was already complete, and the recording footage was staged for the camera. However, it’s the only film of Floyd in the studio circa Dark Side… and a rare sight of the band at work.

Maben’s attempts to film the band in the Abbey Road canteen, eating and chatting, have a tooth-pulling quality because Pink Floyd have never been comfortable talking about themselves or their music.

Their responses to Maben’s questions are defensive, although he does get Waters to admit that they deal with stresses and strains “by pretending they’re not there”, which is more illuminating than Mason’s obstinate demand for a slice of apple pie “without any crust”. Gilmour’s retort in the studio when the engineer complains about feedback – “Where would rock’n’roll be without feedback?” the guitarist asks – is probably the only genuinely natural clip.

The revised Pink Floyd Live At Pompeii eventually went on release in 1974. “I tried desperately to find a better title,” says Maben. “It seemed to me too flat, too descriptive, too pretentious. I was looking for something more down-to-earth, more crunchy. In the end the title stuck because of Pompeii and because it’s curious to be ‘live’ in a place that’s ‘dead’.”

Even though it was the only Pink Floyd film on the market until 1991, Live At Pompeii failed to live up to commercial expectations. “It got lost in the wash of The Dark Side Of The Moon, and for a long time we received very little reward for our efforts,” says Mason. “So much so that, much later, when a New York film mogul approached Roger at a show to tell him that he had made millions from the film, he was surprised to find that instead of Roger congratulating him he was escorted from the premises.

“We later learned that a lot of paperwork relating to the film had been lost in a fire – proof, as I have learned over the years, that offices of those handling such matters are prone to levels of self-immolation, flooding and invasion by locusts that even Old Testament prophets would have found unbelievable.”

In the early 00s Maben was approached about making a DVD featuring additional footage. “It was at that time that we learnt of a disaster,” he says. “The 548 cans of negatives and prints had been incinerated by an employee of the Archives du Film du Bois D’Arcy in order to make extra space for more recent films. Very depressing.

“But I remembered that I had kept at home some black-and-white material shot during the audio mix of the film – some vocal overdubbing on Echoes with David and Richard, and some great out-of-focus interviews of the band talking and making fun of everybody, including themselves.”

This material, along with space footage from NASA and the BBC was used for the Director’s Cut on the DVD, while the original concert footage is preserved on the extras.

Maben’s final thoughts on Live At Pompeii? “A film of modest pretensions that will probably never be finished, with bits and pieces added here and there over a period of many years”.

Hugh Fielder has been writing about music for 50 years. Actually 61 if you include the essay he wrote about the Rolling Stones in exchange for taking time off school to see them at the Ipswich Gaumont in 1964. He was news editor of Sounds magazine from 1975 to 1992 and editor of Tower Records Top magazine from 1992 to 2001. Since then he has been freelance. He has interviewed the great, the good and the not so good and written books about some of them. His favourite possession is a piece of columnar basalt he brought back from Iceland.