November 11 sees the release of Pink Floyd’s The Early Years 1965–1972, a 27-disc box set, including unreleased live and studio material, rare concert footage, replica sleeves, collectable memorabilia, feature films, BBC radio sessions, remixes, out-takes and much, much more.

If Pink Floyd still technically exists, the death of keyboard player Richard Wright in 2008 means that drummer Mason is the only remaining original member. The only one who was there at the very beginning, when Floyd travelled in a Transit van and played ‘happenings’ at tiny clubs such as London’s UFO, and is still there at what could possibly be the end, travelling instead by private jet and playing the biggest concert venues on the planet, along the way having sold God-knows how many millions of albums and played to a total audience of zillions.

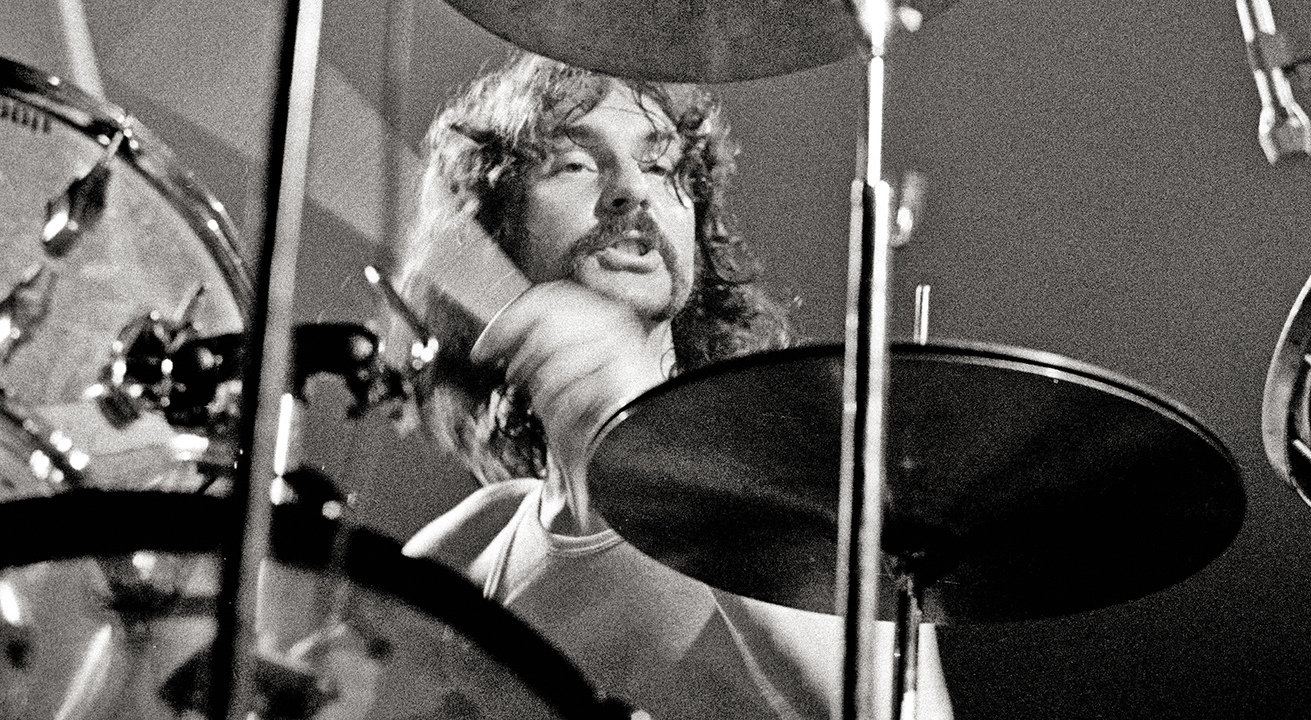

While Mason was in Germany for a press conference, we collared him to speak to him about The Early Years, later years and the years in between.

Is there a massive Pink Floyd archive somewhere, and did you start to clear it out now that the band is officially over?

The archiving was something I started doing a long, long time ago. I just started on my own, and it was this labour of love. So it wasn’t done very well. Eventually things started to work out when the others agreed that it would be a good idea to have an archive – do it properly, get someone in who was a professional. I went to visit Apple [Records] and saw their archives and saw how they did it. And I realised that we’d got some of it right, but I learnt about archiving from them, really. Because I was very impressed with how careful they were. And I think I also realised how important it was that I got involved, because I think Apple sometimes struggled, because The Beatles are not very hands-on with archiving. Although I think that may have changed recently, with the film that’s just been released.

We thought you had used all archival material for the 2011 remasters, and now there are twenty-seven CDs of previously unreleased material.

It’s a ridiculous amount. But the thing is, we’re not going to do this again. Even I know that. And so there is a situation where you go: “Well let’s make sure we do all of it, then.” Because the sort of issues that come up are: do people really want Atom Heart Mother as it was performed in England? Let’s say – Atom Heart Mother as it was performed before we did it with an orchestra, which is really interesting; Atom Heart Mother as it was performed in its early stages, without an orchestra, later stages… And the answer is that we might as well put it out. Because for the people who really want that sort of thing, they can have it.

Including a rather nasty feature on German television accusing Floyd of pure self-indulgence with Atom Heart Mother and stating: “They’re not revolutionary any more.”

I’d forgotten about that. But of course that was really important, this thing about: ‘Were you an underground band, or were you commercial?’ And ‘commercial’ was such a dirty word. I suppose we probably tried to steer a course. Because we owed our survival at times to being non-commercial, ostensibly. It’s a curious place to be, between wanting to be successful – needing to be to survive – but having to sort of work to an audience who didn’t want you to be more successful than you could be.

Are the early years, 1965 to 1972, your favourite time with the band?

No, I don’t have a favourite time. There have been moments that have been difficult. You know, towards the end of The Wall recording when Rick was pushed out, and so on. Really unpleasant. But there were loads of good times around then as well. And when we got better at working. I look back very fondly on driving around in a transit van, four of us and two road crew. Equally, I love being in a private jet with two hundred road crew. You know, it’s not like happy days/bad days, it’s my life. And it’s been that mix of good and bad every day.

Even though at this point everything was brand new, and you were experiencing weird moments such as miming to a playback on French TV? Talking of which, why the cowboy hat?

I don’t know! No idea, I mean, that’s the thing. A lot of stuff was just done on the nod, just because it was there. Someone probably gave me the cowboy hat, and that stuck with me for about three years.

How did it feel to watch and compile all this old footage?

Nostalgia. Because some of it you just think: “Pretentious”. Some of it you think: “Actually, that was quite good.” I always listen to my drumming in a very critical way. But actually I look at some of that and think: “Hmm, that was quite good.”

An extraordinary mix of emotions. We started archiving these maybe seven or eight years ago, but of course some of them I haven’t seen for a long time. And every time you see them something else comes up that you think: “Why was I always wearing a fur coat?” And as the clips went on, the coats got bigger and thicker. No wonder I kept that slim figure. You get caught up in all sort of detail, of what you’re seeing. There’s an element of sadness seeing Syd in his prime, and also seeing Rick, of course.

The extraordinary thing is that when we first even started assembling this project we really thought we were short of material. We thought we just didn’t have things. But there is so much stuff there. And once you know where to start looking – particularly the news services and sort of Pathé in France and all the American stations and so on – it’s really surprising. And you find yourself weeding things out rather than scrambling for material.

It’s amazing to see David Gilmour with a full head of hair.

He was a real glamour guy. He looked great in the pictures, with the long hair and the hat. He was a proper pop star, our David.

There must be a reason why David still plays Floyd’s Astronomy Domine, which was written by Syd, in all of his live shows. You created something that was so naïve and so charming that it lasted for almost fifty years.

Yes. And the trouble is that when asked about it one has no idea. I mean, it’s almost one of those things that you simply can’t explain it yourself, because you just did it. But it’s interesting when other people outside look at it and sometimes give what they think the reason is for the longevity of what we’ve done; why did we last for forty years and so many great bands sort of came and went?

From the outside those nights at the legendary UFO club in London seem fantastic. Three ninety-minute sets, starting at midnight and lasting until six in morning, everybody on LSD or whatever. That must have been wild.

But if you had been there it wouldn’t have been that. With hindsight you think: “This was groundbreaking.” But at the time you’d just thought: “This is really sort of weird, but fun.”

When we were playing at UFO the evening was not entirely about Pink Floyd. It was the counterculture. So there were poetry readings, there was a light show that was not our light show that went on throughout. There were exotic creative dancers. The idea was it was mixed-media. Sadly, within six months that was gone and it became a commercial music thing. Once the record companies were involved, music was the earner. You could sell a ticket on the music, but people wouldn’t pay for poetry and creative dance.

- Pink Floyd - The Early Years 1965-72 album review

- Nick Mason to host Pink Floyd The Early Years screening

- The 31 greatest Pink Floyd songs ever written

- Pink Floyd Quiz

Now, for you is flying helicopters and racing cars a substitute for not being able to make music with Pink Floyd any more?

No, they’re not. But what I’ve always said about helicopters and cars is they’re a wonderful complement to music, because they’re so different in terms of how you have to organise yourself to do them. I still play drums, and I still do quite a lot of things with music. But the car thing has always been the thing that I do that is very different. Because you do it on your own. You cannot be a drummer on your own. You have to have a band to make it work. Otherwise it’s gymnastics, just playing – for me. And what I like is the magic of when you’re playing, and actually there’s a bass part, and a guitar and whatever. The great thing with motor racing is you’re the only guy at the wheel. It’s entirely down to you.

You’re planning a Pink Floyd exhibition at the Victoria & Albert museum in London, similar to the recent David Bowie one. You’ve already hinted that there are probably fewer exhibits than the Bowie one when it comes to Pink Floyd, though.

Much less. We didn’t have costumes, ever. So there’s a couple of shirts and a pair of trousers. But I think what we can do is something different. Explaining how we made the loops work when we’re making Dark Side, or how some of the things that were done at EMI, at Abbey Road – phasing, flanging, some of the guitar sounds, the electronics – worked and let people understand how they work and what they do.

Syd’s story is pretty complex. Would you say he was a genius that the rest of the band didn’t know how to deal with?

I’m not sure it was complex, so much as we just simply didn’t know what to do. I think there were two things. One is we didn’t know what to do, but also we were quite selfish. We wanted to be a pop group. We wanted to be on television, we wanted to sell records.

Syd had undergone a transition, and I think Syd was going: “Do you know what? I’m not happy with this commercial thing. I’d like to be an artist.” And I think he probably would’ve wanted to go back to painting. He didn’t want television, he didn’t really want to tour. I don’t think we ever got into any discussion about the performing, but I suspect all of that was not what he really wanted. I don’t think it would have saved him if we’d just stopped there and then. I still think he’d probably have done the acid and gone slightly off key.

It would have been interesting to see what would have happened to Pink Floyd had Syd stayed and been there in the later stages of the band.

It is interesting. I think Roger [Waters] was strong enough that he would have developed as a writer anyway, so maybe that would have changed. But if Syd had stayed we might never have had David Gilmour. And so we’d have probably spent more time on the sort of whimsical thing, and I think that would have lacked that melodic thing that David has that’s so special.

Obviously there are lots of cases when the singer has left a band and the band has changed, but it hasn’t had the same kind of effect. If Syd hadn’t gone, then arguably most of the music that came from Pink Floyd afterwards would never have developed in that way.

What can one say? There are some really interesting situations where bands have lost a key person and changed dramatically. For me, I think Fleetwood Mac are perhaps the sort of favourite example of changing radically into something completely different but still very good. And like Genesis when Peter [Gabriel] left and Phil [Collins] took over.

The transition for us is a little like that. And it’s really surprising that we went from, you know, Roger writing Doctor, Doctor – which I think is a particularly average song – on the first album to writing Set The Controls, which is the beginning of what I think was great songwriting. It’s really odd, again, looking at some of that film [in the box set] and you see David miming to Syd’s track, which is really odd [laughs]. I still am surprised that we had the confidence – the faith, I suppose – to continue without him. It was astonishingly easy, because we’d all suffered so much from this thing of having a loose cannon, when the rest of us really wanted to continue, and play. And there was use of the word ‘commercial’, but we wanted to be successful. I saw the new Beatles film [Eight Days A Week] last week, and there’s a moment in that where Paul [McCartney] talks about it. He talks about having faith, and having faith in a band. And it gives you such strength to carry on and deal with audiences who are really, really unhappy to see you!

Pink Floyd have made some of rock’s most successful concept albums. How important did that become for the band?

I think we tended to feel that after Dark Side we did want to avoid becoming a sort of concept album band. It had sort of taken over as the new way of doing things, and it felt like a really bad idea to do that as the next project. And Animals was certainly not a concept album. What we did do is try to knit the pieces together with the idea of the animals theme, but there’s no specific relationship between those. Whereas The Wall is absolutely a concept album. So again, I think one tends to approach every album as a new piece. I mean, with hindsight one looks back now and you see a sort of progression through the records.

And what’s interesting again about this collection is that it contains… In my opinion, particularly Atom Heart Mother was really not a cul-de-sac, but it’s not part of our regular progress – Piper to Saucer, really Saucer to Meddle – in terms of how we developed and how ideas developed. I really enjoy looking at this – apart from how much longer our hair gets. We do become a bit more proficient on the instruments. And it sort of gets more complex, and I like that.

When you did a new album, to what extent did you have a concrete idea of what you were going to do before you went into the studio, and to what extent did it just develop as you got in there and started playing?

Well, I think the main thing to make clear is that we never, ever found the perfect way of working, so virtually every album was made with a slightly different way of tackling it. So there are differences between, let’s say, Piper, where Syd came in more or less with most of the songs formed, apart from particularly Interstellar Overdrive, which was improvised more of less from beginning to end, and The Wall, which was almost all pre-written by Roger, and Endless River, which was almost a return to the thing of playing together until we found what we wanted to develop.

Dark Side was fairly structured. We decided outside the studio what we needed to construct in the studio. Whereas Wish You Were Here was a matter of going into the studio and hanging around until we eventually could find something that would work into an album. I mean, for what it’s worth, now I look back on it and I think, really, we made a mistake, and we should have toured with Dark Side for more or less a year. We have no real record of what the show looked like at the time. We’ve got various early recordings of it, but we should have done more touring work then, and then gone back into the studio. We went in far too early, and were trying to follow Dark Side by doing something different, and really struggled for a long time.

Floyd also spent a long time on the road playing something live before recording something in the studio, so you had a chance to adapt it, to change it, to see how audiences reacted to it.

Yes. But the thing that put paid to that was the business of bootlegging. There was the feeling that if you developed it on the road, developed it live, it would’ve been out as a bootleg years before you actually finished it in the studio. And so we had rather changed our approach. Which is a shame in a way, because actually bootlegging probably – I think compared to what happens now in terms of the way music is distributed – wouldn’t have been quite such a problem.

How do you feel about the ways music is distributed now?

Well… [laughs] They’re terrible! I feel very sad when the cheques don’t roll in like they used to. But in our case we had the golden era of it. What does worry me is about young bands now making a living. It’s really difficult. I think streaming is almost certainly the future of music distribution, because it works really well. But it really needs to be expanded to an enormous extent, so that these tiny payments actually build up into something that’s worthwhile, specifically for young musicians. Because they certainly can’t make money playing live. And if there’s no money off the recorded music either it’s so tough. When we kicked off, in 1967, there was the ladder of success. Now, half those rungs, particularly at the bottom end of it, are just missing. And there’s no easy way to actually monetise any of the things that we did fifty years ago.

That’s the business side. But the other side is that these days, because of streaming, increasingly people tend to listen to individual tracks, instead of a full album and in the order it’s sequenced. So in that sense you were lucky that you could use the album format, which has got lost now.

Yes, I think it has. But the interesting thing is I think all these things can come back, you know? This revival of interest in vinyl – it’s still very small, and I can’t see vinyl coming back [laughs] as the main way of producing music, but I do think it might give people the idea of listening in a different way. And if that happens, then people will start constructing music in a different way.

Are you happy with David’s decision after The Endless River to stop the band and declare it done with?

Am I happy with it? I’ve seen this before. That if you don’t say something, what they start doing is saying: “Yeah, well, I like your solo work, but when are you going to get back to proper work?” So I understand why he would want to sort of say: “Look, really, I’ve done this.” My view now is that if David says that, that’s what Roger said twenty years ago. So that means I’m now in charge. I just have to find some more people! [laughs]

Do you think Pink Floyd will ever return to the stage?

The answer really is: I’ve no idea. I think there’s no enthusiasm from David particularly. And Roger is, I mean, in theory no longer part of the band. Having said that, what I think and hope would still be the case is that if there was another Live Aid or a situation where there would be a real purpose in playing again together for something a little more altruistic than making the money, I think the others would step up and do it. And I’d hope that something like that might be possible.

So that’s a “definitely maybe”?

I’d always say it could happen, yeah.

Which is your personal favourite Pink Floyd song? Is there one you could pick?

Not really. Because there are songs that I like, but the songs that are favourite I suppose are things… Set The Controls, for one song, just because the drum part I think is more sophisticated than most of the others. And I love Comfortably Numb because of the structure of it. I really like the fact that the drum part is so minimalist. It’s almost half a drum part, you know? That there are actually bass beats that are deliberately missed in order to empty the thing out. And then by the end of the song, the whole guitar outro, it’s a full-on anthem.

Do you wish now that you’d taken more drum lessons?

I still wish I’d taken drum lessons. Not more, any!

The inside story of Pink Floyd's The Early Years 1965-1972 box set

Why I love Pink Floyd's Piper At The Gates Of Dawn, by Chris Cornell