Banjo player, folk music aficionado and actor/comedian Billy Connolly once described The Dubliners as “folk music’s Rolling Stones”. If that’s the case, then The Pogues were its Sex Pistols: controversial, outspoken, unapologetic, but ultimately revered and respected for breaking the mould, and evolving the Celtic folk sound. Released towards the end of summer 40 years ago, The Pogues’ classic second album, Rum, Sodomy & The Lash, was a remarkable progression from the previous year’s debut Red Roses For Me – in terms of lead vocalist Shane MacGowan’s songwriting as well as the band’s rapidly accelerating popularity and notoriety.

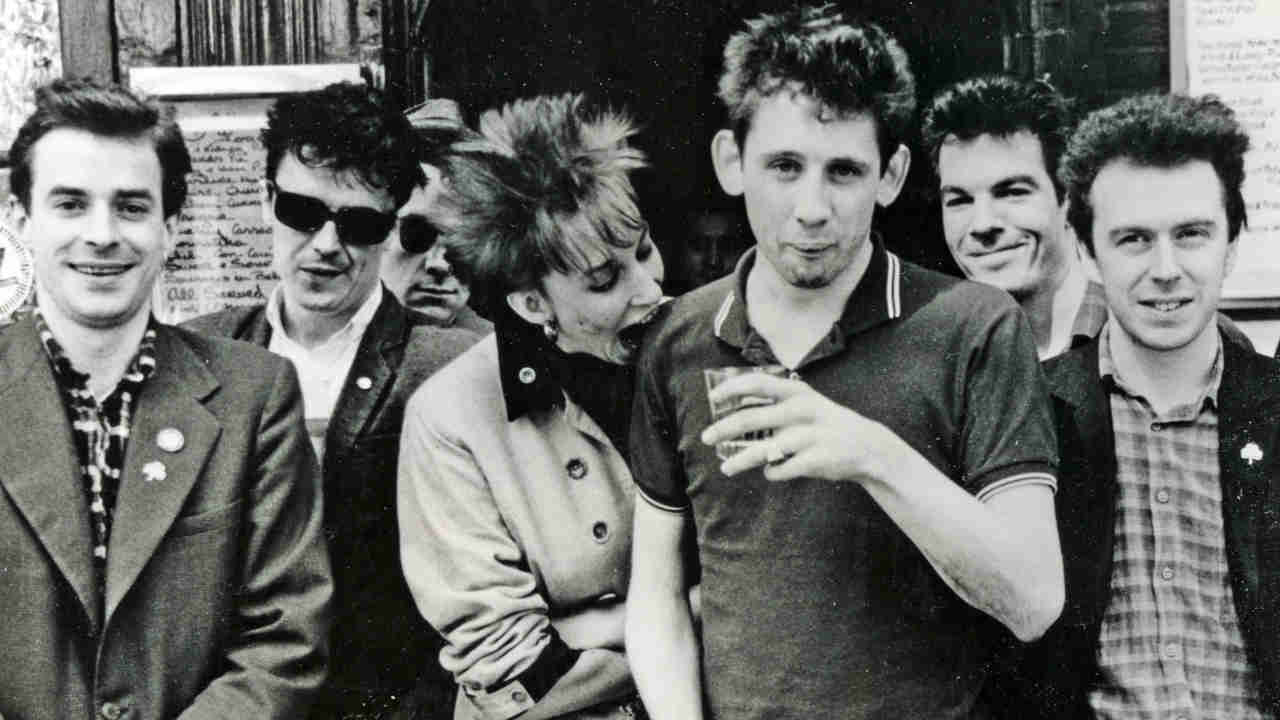

Formed in London’s King’s Cross in 1982, The Pogues were originally named Pogue Mahone – an Anglicisation of the Irish phrase ‘póg mo thóin’, meaning ‘kiss my arse’. (Shane’s previous band, punk rock upstarts The Nipple Erectors, similarly abbreviated their name to the slightly less puerile The Nips).

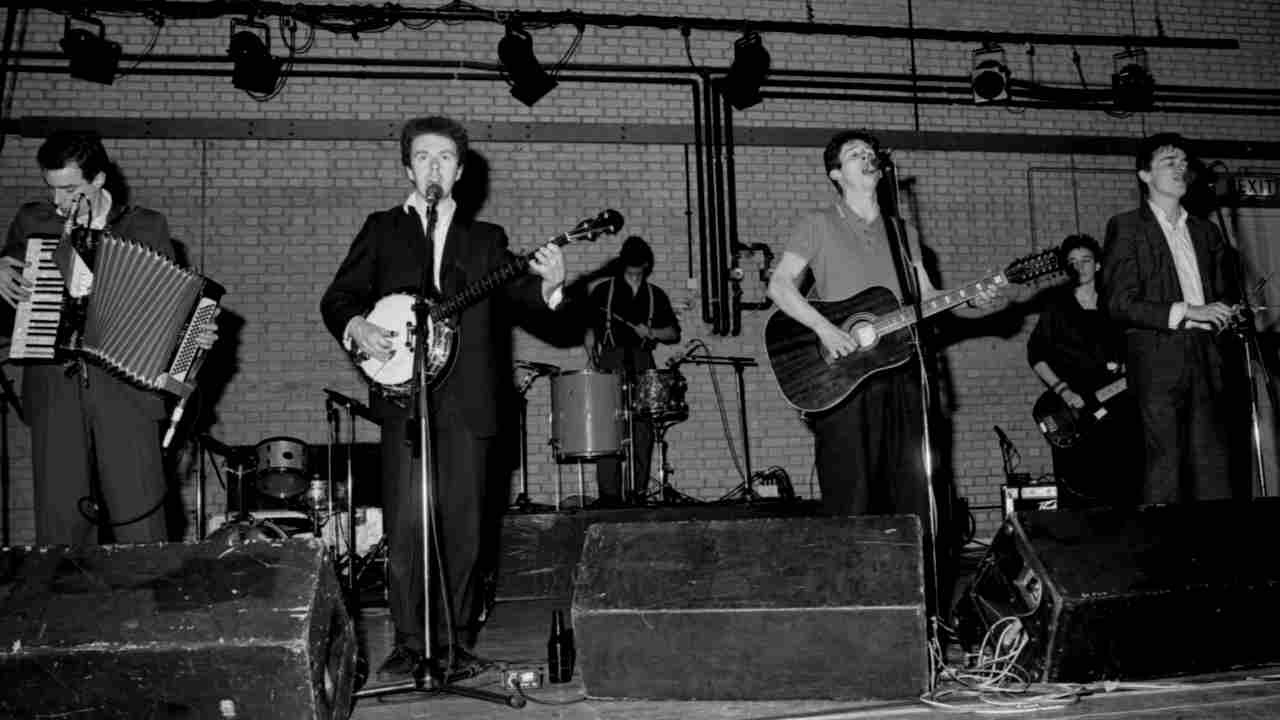

With their punk background, their singer’s insatiable thirst and the exuberance of their early material, it’s easy to assume that life in The Pogues followed a clichéd rock’n’roll template of wild living and non-stop partying. But the famously raucous party atmosphere of the band’s live shows belied the dedication of the self-taught musicians.

“I wouldn’t say it was that chaotic,” says tin whistle player and vocalist Spider Stacy. “We were following a steady trajectory; we were getting more and more popular. Shane’s songwriting was just expanding.”

“There certainly was a fair amount of hard drinking,” says drummer Andrew Ranken. “But we were also working hard. There was a degree of professionalism and discipline, if somewhat unconventional and hard to recognise at times. We liked to get things done.”

Rocketing out of the vinyl, the three-minute blast of The Sick Bed of Cúchulainn is a perfect opener for Rum, Sodomy & The Lash: energetic but shot through with darkness and death while retaining an indefatigable determination. Shane reimagines Irish folklore warrior Cú Chulainn on his deathbed with operatic tenors John McCormack and Richard Tauber singing by his side. The song also name-checks Irish Republican Frank Ryan, who fought in both the Irish and Spanish Civil Wars. Indicative of MacGowan’s prodigious literacy and historical knowledge that informed his songwriting, it follows a similar – yet amped-up – narrative to traditional folk standard and Dubliners favourite Finnegan’s Wake; the protagonist is thought to be dead but revives to carry on drinking and carousing.

“There’s a doughtiness there,” says accordionist James Fearnley, on how the opening track epitomises the album’s overall theme. “He’s just going to keep going. There’s a determination; despite the circumstances, we’re all going to live”.

The album title was suggested by drummer Andrew Ranken from an alleged quote by Winston Churchill about the British navy: “Don’t talk to me about naval tradition. It’s nothing but rum, sodomy and the lash.”

“It certainly wasn’t meant as a description of life in the band,” says Andrew. “I think I might have come across it through reading George Melly’s autobiography Rum, Bum And Concertina. Certainly not from reading anything by Churchill, which I’d run a mile from. I don’t think I was terribly serious about it, I just threw it at the wall and it seemed to stick.”

The album’s morbid mood is reflected by its sleeve. Suggested by Jem’s wife Marcia, it features the band members superimposed onto characters on The Raft Of The Medusa, a bleak 18th-century painting by Theodore Géricault that depicts dying and incapacitated shipwreck survivors floundering in turbulent seas, desperately clinging to the remains of a boat in anguish and despair, searching for a route to survival. It’s the ideal image to express the dark and haunted songs: the anti-war Wilfred Owen-influenced A Pair Of Brown Eyes and cover of And The Band Played Waltzing Matilda; the exhilarating but lachrymose Sally MacLennane; the plight of the Irish labourer in Navigator; the distressing ballad The Old Main Drag; the anti-imperialist satire of Billy’s Bones – and even the fate of an American Robin Hood-style folk hero.

Spider’s gravelly tones take lead vocals on that cover of bluegrass standard Jesse James – his version inspired by Ry Cooder’s recording from the soundtrack of 1980 western The Long Riders. Despite its Americana roots, the song is a natural fit with the rest of the album: poignant and sombre despite its upbeat celebratory nature. Its inclusion emphasises the similarities between Americana and Irish folk, a recurring Pogues subject explored further in the following album – their 1988 commercial peak If I Should Fall From Grace With God – with its themes exploring the Irish diaspora’s emigration to escape homeland famine and poverty at the turn of the previous century.

That influence of evergreen Americana folk rock would also inspire Rum producer Elvis Costello. Already an accomplished singer-songwriter and producer by the mid-80s, Costello later described his task at the helm of Rum, Sodomy & The Lash as to capture The Pogues “in their dilapidated glory before some more professional producer fucked them up”.

“We were big fans of The Specials and their album that Elvis produced,” says Andrew. “We wanted that really open, bleak kind of feel.”

Impressed by Costello’s dedicated professionalism and the end result – especially in comparison to the Rizla-thin production of their debut – the band remember Rum’s studio sessions fondly. Mostly fondly.

“A spark went off between me and him,” says James. “Being a busybody, I wanted to play everything for the overdubs. There was a certain amount of competition between myself and Elvis because I was trying to think of things before he did. If he had an idea for doing a particular overdub, I got shirty with him because he’d just pick up a guitar and go into the studio and do it. I said: ‘We’re the band, you’re the producer.’ So Elvis called a meeting and said: ‘If anybody’s got any ideas, just speak up and do whatever needs to be recorded.’ And Spider said: ‘Oh, James, what have you done now?!’”

So was Elvis an authoritarian producer?

“He had a whip!” jokes banjoist Jem Finer. “He had the lash!”

“We had the sodomy!” Spider interjects jokingly.

“It was really quite sordid…” Jem says, laughing. “No, he wasn’t an authoritarian. He was disciplined and very encouraging.

“He was really very good at his job,” says James. “It sounds brilliant and stands up to time. He really did well with Shane’s voice.”

“I think we had a big influence on him too,” says Jem, “because he then went and made an acoustic album [Costello’s 1986 Americana folk and blues album King Of America]. We fobbed him off with our bass player as well,” Jem deadpans on Cait O’Riordan’s departure. She and Costello became romantically involved after he saw The Pogues live just prior to the album sessions.

Evidently not invited to the band’s 40th-anniversary tour of Rum, Sodomy & The Lash in 2025 – “Don’t go there,” says Spider – Cait O’Riordan didn’t respond to requests to take part in this feature. She was brought into The Pogues as bassist by Shane in 1982 when she was just 17. She was later described by him during the Rum era as “a very strong Irish woman and she could be very aggressive,” as he told author Richard Balls for his exhaustive in-depth biography of Shane, A Furious Devotion. “She was really into her rights as a woman and wasn’t into manipulation,” said Shane.

So do frictions remain between Cait the rest of the band?

“I don’t have a problem with her,” Jem says diplomatically. “I don’t know about other people… When I’ve come across her she’s been fine. But she left the band in 1986.”

Now a DJ with SiriusXM radio, Cait revisited her beautiful soaring vocal on Rum’s striking cover of I’m A Man You Don’t Meet Every Day for Shane’s funeral in 2023.

Equally arresting, Shane’s composition A Pair Of Brown Eyes was chosen as the album’s lead-off single. Demonstrating that The Pogues were much more than a one-trick pony following the debut’s furiously paced songs of drinking ’n’ fighting, the sorrowful ballad marked a new direction. In the style of a classic folk song, it takes the form of a moving tale recollected by its protagonist. In this case, a war veteran recounts the grisly details of his life with only the memory of his lost lover’s eyes to keep him alive. It quickly became a favourite of both fans and the band themselves.

“It’s a great song, and lovely to play live,” says Andrew. “It has such a strong melody and that massive swing.”

Their first single to chart, A Pair Of Brown Eyes firmly established Shane’s talent for songwriting and lyrical storytelling. While he composed all the original tracks on Rum, the album was also the beginning of his co-writing partnership with Jem. Together they came up with ghostly instrumental, The Wildcats Of Kilkenny, featuring blood-curdling screams and sinister metallic strings imitating razor-sharp swiping claws.

“Before the band even existed, Shane would teach me songs and I was sort of playing along,” says Jem. “I’d inadvertently make up instrumental bits. But I didn’t actually realise I was writing music, because I was pretty new to playing,” continues the self-effacing and modest musician. “But they would find their way into things like the intro to Boys From The County Hell and the instrumental section of Dark Streets Of London [both from debut Red Roses For Me]. So that’s how The Wildcats Of Kilkenny came along. Then I would start writing songs but thinking that no way my lyrics would be the lyrics; they were there for Shane to change. So we’d get together and I’d play him bits that I’d written – bits of tune or embryonic songs – then he’d play me stuff and sometimes we’d go: ‘That would really work with this’, or he’d take something and work on it. We didn’t stay together writing for days on end until we got something, we’d meet up and exchange ideas and make cassettes.”

While Jem began his songwriting with Pogues instrumentals, later in the band’s career, he’d go on to co-write Pogues classics with Shane – Bottle Of Smoke, Fairytale Of New York and Sunny Side Of The Street – and his sole compositions the glorious Misty Morning, Albert Bridge and the Eastern-tinged The Wake Of The Medusa. As Jem’s songwriting matured and evolved, Shane said he’d no longer rewrite lyrics. “I didn’t think that was always the best idea,” says Jem. For Sunny Side Of The Street, on Hell’s Ditch, the band’s final album with Shane, Jem purposefully stopped writing so many words; he simply wrote just the song title in order to galvanise the lyricist.

So did Shane gradually lose interest in songwriting throughout the band’s career?

“I think he sporadically lost interest before we even started,” says Jem. “He was often a difficult person to motivate. It would take weeks to even do the simplest thing. There was endless procrastination. But then, great focus.”

Conjecture and speculation persistently followed Shane’s alleged history as a rent boy in London during the 70s. It was often rumoured that the lyrics of Rum’s most affecting track, The Old Main Drag, a bleak and tragic tale of a harassed male prostitute in the dark underbelly of London, were at least semi-autobiographical: ‘In the dark of an alley you’d work for a fiver/For a swift one off the wrist down on the old main drag.’ With its mournful uilleann pipes and Jem’s measured banjo picking, The Old Main Drag is a melancholy tale of woe before its dramatically abrupt vocal ending suggesting death.

“There was an item in the news about some kid being found in a subway,” says James, “who came down from Wigan, because he had his ‘dancing bag’. [Referenced in the lyrics, ‘my ole dancing bag’ was how Northern soul fans referred to their kit of non-work clothes kept for strutting their stuff at renowned nightclub Wigan Casino]. It’s about survival,” James says of the song’s theme. “And against massive odds. It’s hard out there, and that song’s about how hard it is.”

It wasn’t until the release of Julien Temple’s 2020 documentary film Crock Of Gold: A Few Rounds With Shane MacGowan that Shane finally admitted to his past. “Shane used to do it,” says Shane’s wife Victoria Clarke, when Johnny Depp raises the subject of rent boys. “But only hand jobs,” Shane responds. “It was a job in hand,” he says, snickering into his drink.

The release of Rum, Sodomy & The Lash was celebrated with a launch party aboard HMS Belfast moored in the River Thames. “We played in nautical fancy dress,” says Andrew. “A great deal of rum was served by some charming and very camp sailors, and a journalist ended up in the drink – with the drink also in him, no doubt.” The story goes that a sub-editor from music weekly Melody Maker ended up overboard. Equally bizarrely, Hanoi Rocks guitarist René Berg allegedly went in to rescue him.

But even as the album was released, the band had already moved on and were back in the studio, again with Elvis Costello producing, working on a follow-up. The four-track EP Poguetry In Motion was released just six months after Rum, with three sole Shane compositions and another instrumental by Jem, Planxty Noel Hill. Shane’s Body of An American would point the way forward to the Irish-American themes of If I Should Fall From Grace With God, and the EP sessions also included an early version of a new Shane and Jem joint creation – a certain Christmas song titled Fairytale Of New York. The demo had its duet performed by Shane and Cait, with Costello on piano, but the song was of course revisited for the eventual version on Grace. With Cait having departed after the EP’s release, on what became The Pogues most famous song her vocal part was done by Kirsty MacColl, wife of Grace producer Steve Lillywhite and daughter of Ewan MacColl who wrote Dirty Old Town (the folk classic covered on Rum). Cait was replaced on bass by Pogues road manager and aide Darryl Hunt.

But the real treasure of the Poguetry In Motion EP – included as bonus tracks with Rum, Sodomy & Lash since the album’s 2004 reissue – is A Rainy Night In Soho, perhaps Shane’s masterpiece, a timeless and touching love ballad. It was also played at Shane’s funeral in a heartbreaking performance by his friend Nick Cave.

During the EP sessions, Costello and MacGowan argued over whether the final version of A Rainy Night In Soho’s instrumental break should be a muted flugelhorn, or a cor anglais (an alto oboe). They eventually compromised on the flugelhorn (performed by musician Dick Cuthell, best-known for his horn-section work in The Specials) for the UK release and cor anglais for the US version. “It sounded a bit too oily, if you know what I mean,” James says of the latter.

The release of Poguetry In Motion – their first UK Top 40 hit – coincided with the band’s first tour of the USA, and the start of a long love affair with America that would partly inspire If I Should Fall From Grace With God. The band spent their time on the road listening to the new Tom Waits album Rain Dogs and watching the Sergio Leone 1984 gangster film Once Upon A Time In America.

The EP saw the band’s line-up permanently expanded with the addition of guitarist Philip Chevron, who previously played in 70s punk band The Radiators From Space, and Terry Woods, ex-Steeleye Span, on cittern. Chevron had already played with the band for some live dates prior to the recording of Rum, when Jem took a leave of absence for family commitments when his wife Marcia was expecting their second daughter, Kitty. “Philip took over on banjo during that period,” says Jem. “And then he kinda wouldn’t leave! He became the guitar player. Shane decided he didn’t want to play guitar any more – or Philip decided he did.”

Chevron (who passed away from cancer in 2013) officially joined in between Rum and the Poguetry In Motion EP, but was still included in the album artwork. “He still somehow got his picture on the sleeve,” Jem says of the cigarette card-style photos of the band dressed up in period naval garb for the album artwork, “but he didn’t play on it. He was quite an operator… he was on the album, but he wasn’t.”

Shane was eventually sacked by the band in 1991, following the fifth Pogues album, 1990’s Hell’s Ditch, for increasing unreliability wrought by his alcoholism and drug use. Hell’s Ditch was produced by ex-Clash frontman Joe Strummer, who would replace Shane for ensuing live dates, but Spider took over on lead vocals for their final two albums: 1993’s Waiting For Herb and 1996’s Pogue Mahone. Meanwhile, their former frontman would record two albums as Shane MacGowan & The Popes – 1994’s The Snake and 1997’s The Crock Of Gold. Shane reunited with The Pogues for occasional live dates between 2001 and 2014, but despite the occasional guest appearance on song covers, he released no further material or albums before he passed away in 2023.

The Pogues would have a significant influence on the 90s Celtic punk movement – bands like Dropkick Murphys, Flogging Molly, the Real McKenzies et al. But much deeper, in the same way that they pushed the envelope of Irish folk in the 80s with Rum, Sodomy & The Lash the last few years have seen a true renaissance of the music, with a fertile upsurge of acclaimed bands and artists. Influenced by The Pogues to a greater or lesser degree – even if just by having the door opened – Lisa O’Neill, Lankum, John Francis Flynn, Ye Vagabonds, Junior Brother, CMAT and the Mary Wallopers are taking the genre in an entirely new progressive and alternative folk direction, while respecting its rich history.

In a somewhat precocious question asked of MacGowan at the time of Rum, Sodomy & The Lash’s release in August 1985, the NME’s Danny Kelly wondered how Shane would like The Pogues to be remembered. In hindsight, his answer now seems to sum up the spiritual soul of that seminal album: “As being very good, as meaning something to quite a lot of people,” said Shane. “As having a sense of humour, as being real, down to earth. I’d like it to be said that we reflected reality without being deliberately miserable or offering unobtainable escapism.”

The Pogues feat. James Fearnley, Jem Finer, Spider Stacy, and special guests celebrate the 40th anniversary of Rum, Sodomy & The Lash with six UK shows in May