There’s never been anyone in rock’n’roll quite like Chrissie Hynde. Of course, there were women who rocked before she arrived on the scene 40-odd years ago, such as Wanda Jackson, Heart’s Wilson sisters and Patti Smith. But Hynde synthesised the influences of all those women into something new, and topped it off with great songwriting chops and her distinct vocals. Still, Hynde might baulk at the gender reference.

“My role models were musicians,” she tells me. “You know, my role model might have been Jeff Beck. I knew I’d never play guitar like that – but I thought I could look like him! The fact that he was a guy didn’t even [factor] into it.”

Together with the rest of the original Pretenders – lead guitarist James Honeyman-Scott, bassist Pete Farndon and drummer Martin Chambers – Hynde made one of the best debut albums in rock history, and a second that was nearly as good.

After that, tragedy struck. Honeyman-Scott died in 1982 and Farndon followed him a year later, both drug-related deaths. Since then Hynde has soldiered on, with The Pretenders, as a solo artist and in collaboration with other musicians. Along the way she has scored the occasional hit (Middle Of The Road, 2000 Miles, Thin Line Between Love And Hate) and dabbled in various genres, all while remaining true to the melodic but punk-influenced rock that the band established on their debut.

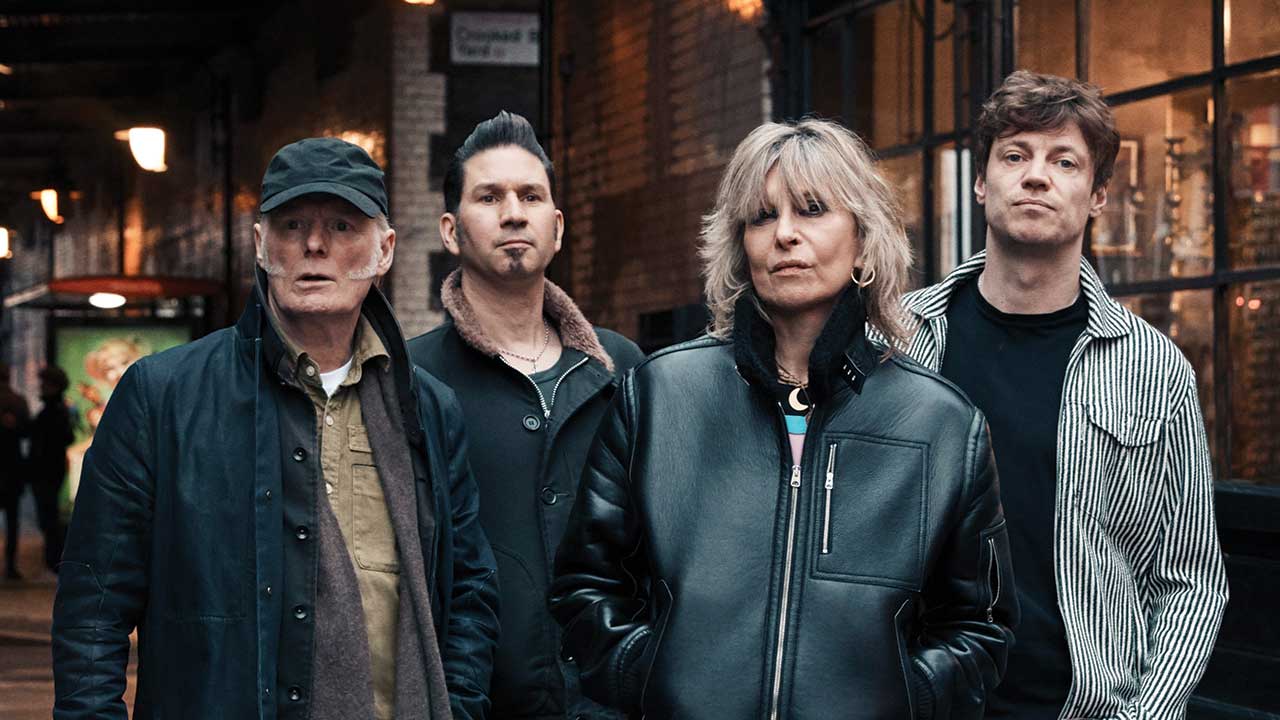

Hate For Sale, released last summer, is the eleventh proper Pretenders album and arguably their best since 1984’s Learning To Crawl. It’s also their first studio record since Learning To Crawl to have all four Pretenders on the cover. (In addition to Hynde and Chambers, the current line-up is completed by lead guitarist James Walbourne and bassist Nick Wilkinson.)

Unlike 2016’s Alone, Hate For Sale is a concise album: 10 songs with a combined running time of just over half an hour. The title track, Turf Accountant Daddy and I Didn’t Know When To Stop (which is about painting) are tight, in-your-face rockers, You Can’t Hurt A Fool and Crying In Public are top-notch ballads.

Didn’t Want To Be This Lonely is a rockabilly tune, Lightning Man is a reggae-tinged tribute to Hynde’s late musician friend Richard Swift. And Maybe Love Is In NYC manages the neat trick of rocking out and being beautiful at the same time.

“Everything we set out to achieve on this album, I think we did,” she says. “So that feels great.”

When Hate For Sale came out, last July, the first thing that struck me was the album cover: the fact that all four Pretenders are on it. The last time that happened was with Learning To Crawl. It makes it look very much like a band album. What was recording it like, and what did each band member bring to the proceedings?

I really wanted to record with these guys. And I wanted to write the album with James, that’s been on the cards for a long time. We actually started writing these songs a couple of years ago, but then we were on tour and were doing other things. Then we got together and finished the songs.

James and I really talked about it a lot: how all throughout our last couple of tours, how we wanted to do an album with a four-piece band. You know, just simplify it. Bring in [producer] Stephen Street, who we both worked with individually before. Martin has a very distinctive style, so he brings his personality. Same with Nick. We have a real solid… I don’t know, chemistry. We have a blast when we play live, and we really wanted to bring that into this album and make it, number one, a fun album.

What can you tell us about the title track, which is also the first one on the album?

That was one of the first songs we wrote. And we thought it was a good title. It wasn’t about anyone specific, it was just more of… I suppose you could say a stereotype. Love Is In New York City is a great track, with beautiful imagery and also a beautiful guitar sound. That actually was [inspired by] a friend of mine who lives in New York, who I’ve known all my life.

When she came to visit me she gave me a T-shirt that said: ‘Maybe love is in New York City’. And I thought: “Oh, what a great title.” That’s where that came from. It’s hard to talk about songs and their origins and what they’re about… I know what an audience wants to know, it’s just hard to talk about it. There’s the feeling that if you have to explain a song, then the song didn’t really work. But then I get it from many angles.

You know, the process of writing is always different with every song. There’s not really a method. There is for some people. At the moment, I’d like to think this album is kind of refreshing for people who like guitar-based rock’n’roll. Because there’s been many years where it’s all done in the studio, and songs are written by committee. I mean, I’ve seen people try to get together and write. It’s all about writing a hit.

Nothing wrong with that, that’s what traditionally they did in the Brill Building, you know? But this has become more than just about a hit. Burt Bacharach and Hal David would write songs and give them to a great singer like Dionne Warwick. But they tailored their songs [to her], because they knew her voice and they knew she could deliver.

Now – I’m not even criticising, it’s just an observation – someone will write a song, send it to someone they don’t know, [and] the person might or might not reject it. If they don’t use it, they might go to another set of songwriters or another artist. The artist will often change one line and say they won’t do it unless they get a songwriting credit. This album is kind of oldschool.

There’s something autistic about rock’n’roll. It doesn’t really change, you know? Very simple format, but with those four pieces you can do a lot. You can almost evoke anything. I guess that’s what happened when punk came along. The seventies had started, and there was prog rock and it got a little too flabby for a lot of people, so they wanted to deconstruct it.

Anyway, it keeps going around in cycles. You’re a music writer, we could be having this discussion in any bar in the world right now. Everyone’s talking about it all the time. “What do you think about music now?” I don’t mean just in an interview situation, but just the subject. I grew up in the late sixties… You know, AM radio then went into FM radio. AM radio was coast to coast and it was very regional. Every city had its own radio station and its own playlist! When MTV came along it all got filtered into one thing. It had to go first through a video – often a soft-porn video, because some of the artists knew that sold – and that became sorta dance music, I guess.

It wasn’t rock’n’roll any more. If you look at videos that were made back then, they look silly now. The pomposity of it. You can smell the money that went into it. I think we’re at a moment now, especially with this lockdown, of getting things simple again. I mean, I live alone. I don’t cook. You know, if I need something to eat I go to the shop or whatever restaurant’s nearby. But with this [pandemic], the brown-rice hippie in me has re-emerged. And she’s a pretty good cook, as it turns out!

Anyway, I think I’m talking too much.

It’s interesting what you said about quarantine and making people do things themselves again. I’m sort of like that too. I live in New York City. I don’t cook, there are usually restaurants down the street. But in the past couple of months – not that I’ve become Julia Child – I’m cooking for the first time. You know what I mean?

[Laughs] I think everyone’s experienced this. First of all, everyone’s responded to the wildlife coming back. I mean, the birds – I’ve never heard them this loud. Everything’s vibrant out there. And when I say to someone that I’ve actually enjoyed this, almost everyone I’ve said that too says: “Actually, so have I!” It’s like they didn’t wanna say it. But everyone’s appreciated how much they were part of the rat race.

2020 marks forty years since the first Pretenders album came out. Do you ever think about the time when you were making that record, or even just being in England back then?

Well, I was here for a while before I recorded the album. I didn’t know what I was gonna do when I came to England. I just wanted to see the world. I was pretty sure I wasn’t gonna stay in Akron, and I wanted to be in England because that’s where all my favourite bands were from. There you go, I was an Anglophile. I put a lot of effort into getting that band together and meeting the right people. I couldn’t get it together in the punk scene because, frankly, I was a little more musically diverse.

Being an American growing up on radio, and I was a couple of years older than most of the people in punk. They all grew up on David Bowie and Roxy Music, but I grew up on James Brown, Bobby Womack… By the time I was twenty-four I thought I was too old to get in a band. Then punk came along. There were some people in bands from New York that were even older than me, and I thought: “Fuck it, I’m doin’ it in that case!”

But twenty-four, that was about the time you got out of a band. You know, think about what Otis Redding did. He died when he was, what, twenty-six, twenty-seven. Huge legacy of music! Tim Buckley! Died when he was twenty-eight. Ten albums. Amy Winehouse died when she was twenty-seven. She didn’t make that many albums, but she made a major impact, with an original voice.

Jimi Hendrix was another.

Hendrix! You know, my man. I’m looking at a picture of him right now. And then you’ve got Bob Dylan, who is going strong and he’s pushing eighty! He’s doing some of the best work he’s ever done. Listening to [Dylan’s latest album, released in 2020] Murder Most Foul jolted me out of this weird frame of mind when the lockdown started.

It was like: “What the fuck’s going on?” Like everyone else, I was sort of adrift mentally. And then someone sent me that song, I listened to it and I thought: “Fucking hell!” It really lifted me out of a sort of malaise. Despite the sombre subject matter, he’s still funny! Bob’s always funny. And it spoke so much to me.

Hate For Sale is out now via BMG