It’s an inaccurate science to try to define music by category and genre. Artists rail against it, critics endeavour to nail it down into the simplest terms, the most convenient definitions and snappy soundbites. But, ultimately, it’s helpful to try to explain the bond that seemingly disparate artists may share. So just what kind of folk is this genre we’re calling progressive folk?

Well, exactly that: folk bands and artists who have dared expand their horizons from the traditional format. At its heart, folk music screams tradition. Folk songs are passed down from generation to generation. They are songs sung in pubs and in living rooms the world over. As such, true folk music is an important historical device.

A heckler at Manchester Free Trade Hall on May 17, 1966 might have called Bob Dylan ‘Judas’ for daring to expand his folk roots, forsake his battered acoustic and pick up and plug in an electric guitar, but in truth folk has often been among the most progressive forms of music. It’s had to be, simply to survive this long. The music has had to change with the times.

In the days before guitars were around, folk music was sung a cappella by default. Then sometimes it was sung a cappella by design. Then, as technology brought us guitars, mandolins, pianos, electric guitars, sitars, the Mellotron and thousands of other instruments, folk music could be played on anything.

Folk artists are at the very heart of forms of rock music. Face it, without folk and blues there would be no rock’n’roll. Without the innovative guitar work of Pentangle’s Bert Jansch or Roy Harper’s intriguing playing, Led Zeppelin would probably have sounded a whole lot different. If Rick Wakeman had not begun his musical odyssey with The Strawbs and embraced their progressive nature, surely Yes would have been an entirely different-sounding beast?

Arguably the most influential and greatest rock band in the world might have developed in a totally different way were it not for their crossing paths with a progressive folky. If Donovan hadn’t expanded his early folky leanings and sat around jamming guitar with John Lennon and George Harrison, The Beatles may not have sounded like the band we know today.

The progressive folkies were (and still are) unafraid to experiment, be that vocally, lyrically, in terms of arrangement, with using extra musicians, orchestras or simply just mucking about with their guitars that they sound so incredibly alien (please stand up Roy Harper and John Martyn). Using fiddles and electric guitars, sitars and gourds, unison vocals and searing guitar lines are de rigeur for our progressive friends, and we must be thankful for it.

The following feature highlights some of rock music’s finest innovators – the bands and solo artists who can be truly defined as progressive folk.

Pentangle

Classic line-Up: Terry Cox (drums and vocals), Bert Jansch (guitar and vocals), Jacqui McShee (vocals), John Renbourn (guitar and vocals), Danny Thompson (double bass)

From: London.

Ever considered the idea of a folk supergroup? Well, if ever there was such a thing, then it’s certainly Pentangle. Two leading lights of the 60s folk revival teamed up to make a glorious cacophony of progressive folk noise. Innovative guitarists Bert Jansch and John Renbourn got together in early 1968 with the crystal-voiced Jacqui McShee, double bass player Danny Thompson and drummer Terry Cox. The rhythm section both came from a jazz/blues background which would be a profound influence on the new band’s sound.

Jansch (a huge influence on Led Zep’s Jimmy Page) and Renbourn had differing guitar styles that delicately clashed and seared and underscored McShee’s soaring vocals. The jazz-inflected rhythms that Thompson and Cox brought to the band supplied a levity to Pentangle’s primarily acoustic folk rock.

Having the wherewithal to realise that rock and folk needn’t be mutually exclusive, the band enlisted producer Shel Talmy (who had worked with both The Who and The Kinks) to shape their sound. They successfully mixed trad folk songs like Let No Man Steal Your Thyme with jazz standards from the likes of Charlie Mingus.

Pentangle had significant mainstream success – their third album Basket Of Light went Top Five in the UK and stayed in the album chart for over six months. Their influence remains profound, and finally this year the band were recognised for their achievement, and the original line-up reunited for the BBC Radio 2 Folk Awards where they were awarded a Lifetime Achievement gong. Oh, and they played too.

Recommended: The Pentangle (Castle, 1968).

The Strawbs

Classic line-Up: Dave Cousins (guitar and vocals), John Ford (bass and vocals), Richard Hudson (drums and percussion), Dave Lambert (guitar and vocals), Rick Wakeman (keyboards).

From: London.

Both Yes’s Rick Wakeman and Fairport Convention’s Sandy Denny spent time with The Strawbs before venturing into their progressive future. The Strawbs’ debut album managed to straddle the lines between folk and more traditional prog rock with songs such as Oh How She Changed and The Battle.

But the band weren’t able to sustain this on their second release Dragonfly in 1970, and founding member Dave Cousins brought in Rick Wakeman. This collaboration was a success and The Strawbs released a genuine folk rock/prog rock crossover album called Just A Collection Of Antiques And Curios.

Recorded live at London’s Queen Elizabeth Hall in July 1970, the record saw the band stretching out and includes an exhilarating performance from Wakeman on Temperament For A Mind. If anything, this was the record that succinctly marked the transition of The Strawbs from folkies to more traditional progressive rock. 1973’s Bursting At the Seams finally yielded the band a hit single in Part Of The Union, but by now their folk beginnings were fading.

Recommended: Bursting At The Seams (A&M, 1973).

The Incredible String Band

Classic Line-up: Robin Williamson (fiddle), Mike Heron (guitar), Dolly Collins (flute, organ and piano), Licorice McKechnie (vocals and finger cymbals).

From: Glasgow.

You wouldn’t necessarily think that Glasgow would be the place from which progressive folk gained its Indian and African influences. But The Incredible String Band took their fiery brand of Celtic folk and mixed it up with some very international flavours. Guitarist Mike Heron and his fiddle-playing partner in crime Robin Williamson effortlessly managed to blend Indian and African nuances to their music.

Things really came to a head after Williamson spent some time in Morocco, resulting in the full-on, impossibly eclectic The 5000 Spirits Or The Layers Of The Onion in 1967 (which also featured Pentangle’s Danny Thompson on bass). Many critics cite it as a psychedelic record, but if that’s not the title of a prog album, we don’t know what is.

Despite its disparate, unusual and, frankly, bonkers songs (with lyrics about singing hedgehogs and random references to Christmas trees), the folk community loved it. The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter followed in 1968, and that was just as trippy.

Recommended: The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter (Warners, 1968).

Roy Harper

From: Manchester.

Roy Harper’s contribution to progressive folk cannot be understated. Rising from the London folk scene of the mid-60s, Harper shied away from interpreting folk standards and focused upon his own material from the very beginning. His early albums consisted of his quirky poetic lyricism backed by his intriguing acoustic guitar playing.

Always trying to push traditional folk boundaries, Harper was inventive with his sonic exploration – an early album (Flat Baroque And Berserk) saw him playing his acoustic guitar through a wah-wah pedal on the track Hell’s Angels. While Hendrix had introduced us to the wah-wah on an electric guitar, hearing the effect on a more traditional instrument was startlingly different.

Harper had always extended the song format, and his defining fifth album galvanised this talent. Featuring just four songs, Stormcock was a stunning piece of work, lyrically running the gamut from lambasting religion (The Same Old Rock – a song that features a sneaky cameo by Jimmy Page masquerading as S. Flavius Mercurius) to Me And My Woman, an epic tribute to the women in his life, underscored by a great orchestral arrangement. Hats off to (Roy) Harper, indeed.

Recommended: Stormcock (Harvest, 1971).

John Martyn

From: Surrey, UK.

A phenomenal guitar player and singer, Martyn’s form of progressive folk changed over his long and distinguished career.

Eschewing traditional folk, Martyn included many elements of both blues and jazz in his early work. This was further enhanced by his guitar trickery. Unafraid to experiment, Martyn ran his acoustic guitar through many effects pedals – everything from distortion (traditionally used with an electric instrument) to flanger and phase-shifter – morphing its sound into something alien and unique.

For many, Martyn’s playing is synonymous with the Echoplex – a unit that puts an echo/delay on to the guitar sound, rendering it distinctive and otherworldly. This process was used to fine effect on the track I’d Rather Be The Devil on Martyn’s 1973 album Solid Air – the title track of which was a tribute to John’s friend and fellow prog folker Nick Drake.

Throughout his career, Martyn encompassed all styles of music into his idiosyncratic playing. He even worked with jazz flautist/saxophonist Harold McNair for his second album, The Tumbler. While remaining a folkie at heart, Martyn pushed musical boundaries throughout his life. And if that’s not progressive, we don’t know what is!

Recommended: Solid Air (Island, 1973).

Nick Drake

From: Tanworth-in-Arden, Warwickshire (Born in Rangoon, Burma)

Underappreciated in his lifetime – he died in 1974 at the age of 26 from an overdose of anti-depressants – Nick Drake nevertheless managed to change the perception of traditional folk music, albeit posthumously. Chronically shy and dogged by depression and insomnia, Drake was never truly cut out to be a performer, but it was these psychological conditions that clearly influenced the haunting nature of his work.

Primarily a guitarist (and one who used some of the weirdest and most innovative tunings imaginable), Drake’s lyrics often reflected his fragile mental state. But it was the combination of his idiosyncratic playing, the affecting lyrics and the skilful orchestral arrangements from his college friend and collaborator Richard Kirby that truly took Drake beyond being just another run-of-the-mill singer-songwriter. His second album (Bryter Later) would even contain elements of jazz.

With only three albums to his name, Drake was little more than a cult figure in his lifetime. He rarely played live, and despite being discovered by Fairport Convention’s Ashley Hutchings, the folk scene never truly embraced him either. He remained very much a musician’s musician until the late 80s when he started to become namechecked in the popular music press.

Today, Nick Drake is probably the most namechecked progressive folk singer in mainstream culture.

Recommended: Five Leaves Left (Island, 1969).

Fairport Convention

Classic Line-up: Sandy Denny (vocals), Dave Swarbrick (fiddle and viola), Richard Thompson (guitar and vocals), Simon Nicol (guitar and vocals), Ashley Hutchings (bass and vocals), Dave Mattacks (drums and percussion).

From: London. Fairport Convention fluttered into existence in 1967 in London’s Muswell Hill. The brainchild of bassist Ashley Hutchings, guitarists Richard Thompson and Simon Nicol, Fairport was a band that initially owed a great debt to traditional American folk music and the up-and-coming West Coast acoustic scene.

Before their debut self-titled album hit the shelves in 1968, Fairport had already swapped their lead female singer Judy Dyble for Sandy Denny. It featured mostly original material, primarily written by Thompson, save for a cover of Joni Mitchell’s Chelsea Morning. Their sound was eclectic enough to gain some attention and the band were even briefly alluded to as ‘the British Jefferson Airplane’.

The addition of Denny took the band on to greater heights though. Fresh from her stint in The Strawbs, she was a familiar voice to the traditional folk contingent. The band’s second album (What We Did On Our Holidays, 1969) mixed things up – the band taking on songs from Mitchell and Bob Dylan alongside traditional English folk tunes.

Unhalfbricking (July ’69) saw the band continue in this vein, but after a tragic traffic accident that killed drummer Martin Lamble the band regrouped to record their definitive statement Liege And Lief. Violin player Dave Swarbrick joined full-time, and the band immersed themselves in the material – from ferocious acoustic riffs to high-voltage fiddle playing, all topped off by Sandy Denny’s stunning vocals.

It would be their defining moment – but it would also spell the classic lineup’s demise. By the close of 1969, both Hutchings and Denny had quit the band.

Recommended: Liege & Lief (Island, 1969).

Tim Buckley

From: Washington DC. S uccessfully straddling the worlds of prog folk and psychedelia, Tim Buckley was one of the most intriguing singersongwriters of the late 60s.

While folk music was definitely at his core, Buckley managed to infuse his songwriting with elements of so many different musical styles – from progressive jazz to West Coast country. Consequently, many Buckley detractors (and even fans) criticise him for his non-consistent sound.

And, as the years progressed, Buckley became more and more interested in jazz – infusing his work with a bravura that is seldom heard in folk. He would use his voice as an avante-garde instrument and as such, 1970’s Lorca album alienated him from many of his fans. Gone was the sensitive, soulful singer-songwriter and in his place was an off-the-wall experimentalist, replete with vocal scatting over jarringly discordant jams.

Sadly, 1975 would signal the end of Buckley’s musical journey as he died from a heroin overdose. But, as far as progressive folksters go, Buckley still remains at the cutting edge.

Recommended: Starsailor (Rhino, 1970).

Steeleye Span

Classic line-up: Tim Hart (dulcimer, guitar and vocals), Bob Johnson (guitar and vocals), Rick Kemp (bass, drums and vocals), Peter Knight (violin, keyboards and vocals), Maddy Prior (vocals).

From: London. When he quit Fairport Convention, bassist Ashley Hutchings needed another project – he wasn’t finished in the progressive world. So he hooked up with established folkies Maddy Prior and Tim Hart to create Steeleye Span. But Hutchings’ tenure wasn’t to last and he went his separate way after three albums.

This wouldn’t spell the end of Steeleye, though. The band had worked hard throughout their existence to be welcomed into the rock world. So they decided to carry on. Capitalising upon a harder, proggy edge, Span released Below The Salt (1972) and Parcel Of Rogues (1973). Big rock guitars fought for supremacy among killer electric fiddles and their by-now trademark harmony vocal lines.

To further their prog folk sound, the band roped in Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson to produce Now We Are Six (which also featured none other than David Bowie on sax), an album of primarily traditional folk songs given the Steeleye treatment. Their commercial breakthrough came in the form of the Mike ‘Womble’ Batt-produced All Around My Hat (1975), and in 2019 the band released their 24th studio album.

Recommended: Parcel Of Rogues (Chrysalis, 1973).

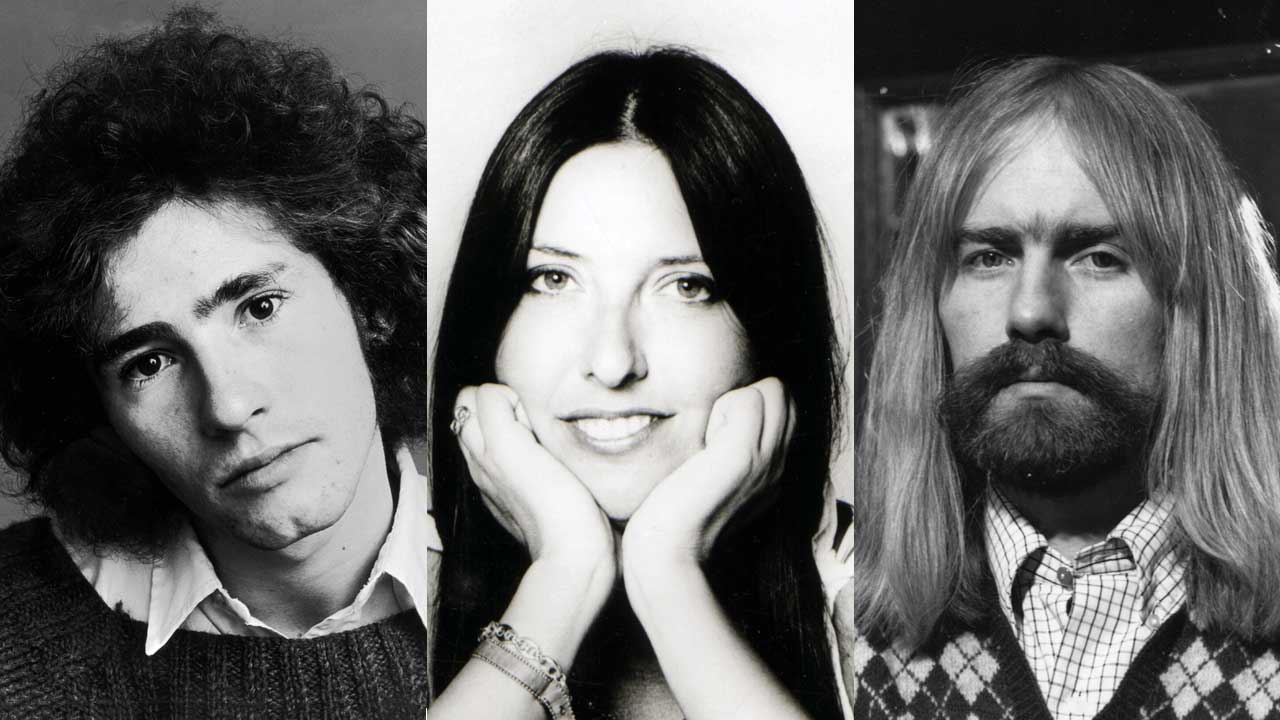

Donovan

From: Glasgow.

They may have called him mellow yellow, but there’s a lot more to Donovan than his 1966 hit. Rising to prominence at the same time as Bob Dylan was making headway in the US, Donovan was often unfairly tagged, or even dismissed as ‘the British Dylan’.

But this was hardly surprising given that both Dylan and Donavan admired the work of Woody Guthrie and other early American traditional folkies. The singer was also influenced by both Scottish and English folk music (he spent time on both sides of the border growing up), and Donovan picked up the guitar at an early age and began to teach himself to play. In terms of guitar playing, fellow folkie Bert Jansch was hugely influential on the young player, so much so that Donovan wrote the song Bert’s Blues in tribute.

Once honed, Donovan’s guitar playing style was truly distinctive – he developed his own trademark ‘flatpicking’ technique – and he is often credited with having taught The Beatles’ George Harrison, Paul McCartney and John Lennon this specific picking style while they were all on retreat in India with the Maharishi.

Donovan was not content with merely writing acoustic, light folk ditties and his sound would soon develop, incorporating jazzy elements (he was a huge admirer of Billie Holliday), psychedelic overtones and thanks to his sojourn in India, sitar orchestrations.

Despite expanding his musical horizons and making his brand of folk as progressive as possible, Donovan still remained a fixture on the UK folk scene, managing to take his audience along for the ride rather than alienate them.

Today, Donovan continues this musical journey and released his most recent album, Gaelia, in December 2022. He's currently preparing for 60th Anniversary shows in 2025.

Recommended: A Gift From A Flower To A Garden (Pye, 1967).