Kosmic kraziness: the acid-drenched Story Of Psych

We take a trip back in time and space and dig where the primitive Big Bang began

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

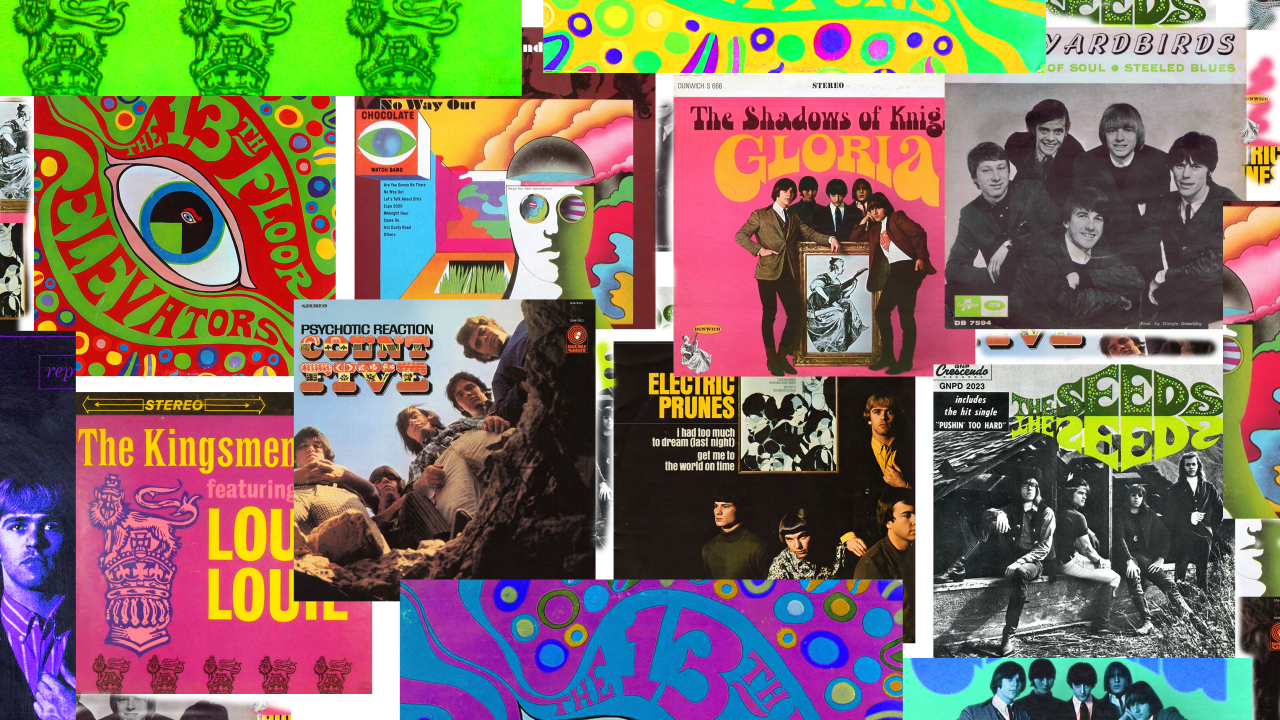

Garage band rock and its mutant spawn, psych rock – a pimply, snotty, inspired, glue-sniffing teen culture that flourished in the last half of the 1960s – had, incredibly, vanished from human memory when, in 1972, Lenny Kaye unearthed 27 tracks of punky gold, accompanied by pithy liner notes, in a two-record collection: Nuggets: Original Artyfacts From The First Psychedelic Era, 1965‑1968. This wasn’t just a quirky curiosity in the glorious history of rock – it was the very plasma rock needs to resuscitate itself every seven years or so.

Nuggets arrived at the low point of rock mojo and soon became a source of inspiration for future punks, grunge dwellers and any other maniac who wanted to crank up the thunder dome again. A Nuggets boxed set including four CDs came out in 1998, and a subsequent collection, Children Of Nuggets took the story from the mid-70s to the mid-90s.

Garage bands were a visceral reaction to the tsunami of the Brit invasion. Groups like The Beatles, The Yardbirds, The Kinks, The Who and the Rolling Stones presented a formidable challenge. They had it down cold: the look, the attitude, Mississippi Delta riffs, quaint accents, enigmatic lyrics and hair. Worse, these foppish posers turned out to be catnip to chicks. Something had to be done.

Article continues belowReaction to the Brit invasion pushed garage band ingenuity to inspired heights. Small-town punks, inner city greasers, frat boys, surfers, disaffected teens and a few unbalanced individuals began tinkering with rock’s turbocharged engine. It meant stripping down the machine, rebuilding the chassis and then adding some newfangled element to grab your attention – distortion, electronics, whatever tricks in the book they could lay their hands on.

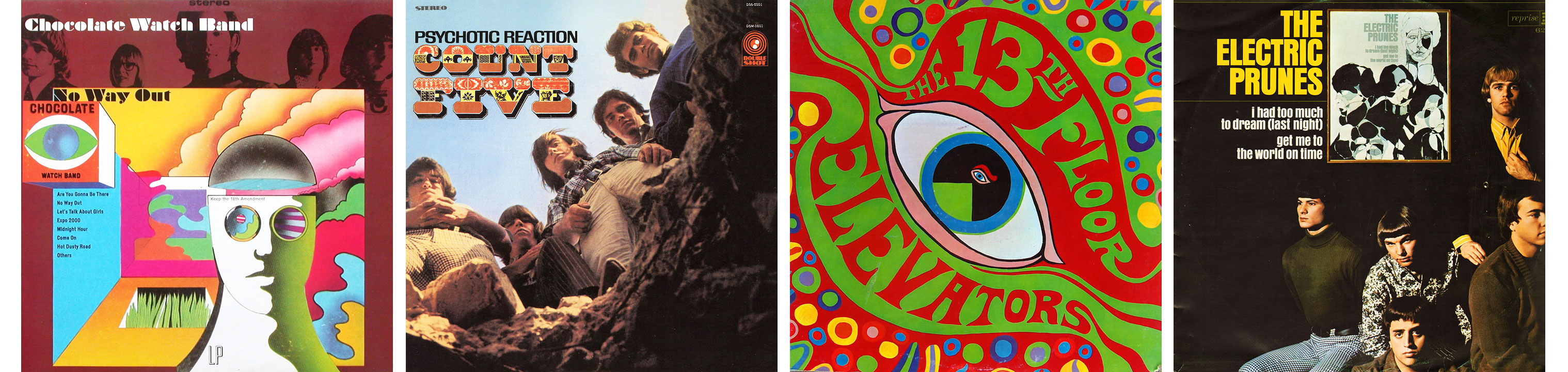

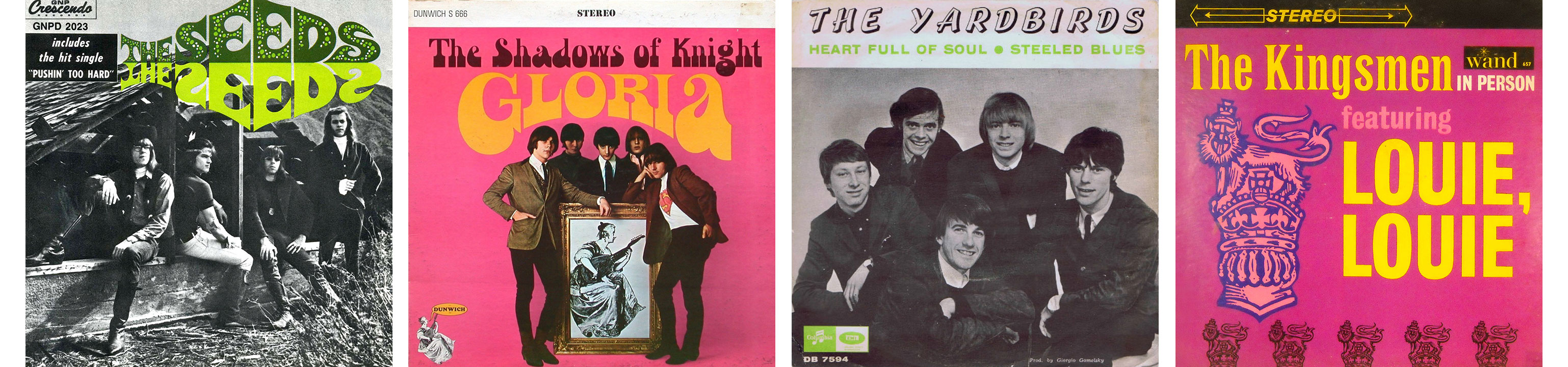

Typical of garage bands’ attempts to move away from The Beatles (except for the haircuts) is Talk Talk by the Music Machine, who used proto‑punk fuzz guitar, Farfisa organ, one black leather glove and a what’s-it-to-ya? delivery to establish their identity. Garage bands’ sound was the bull-in-a-china-shop approach to Brit rock’s finely made goods. Take Louie Louie by The Kingsmen (a repetitive three-note riff with lyrics incomprehensible enough to attract the attention of the FBI), The Castaways’ pared down Liar, Liar, or The Seeds’ defiantly crude, two-chord Pushin’ Too Hard.

American bands came out of a car culture – they thought of singles as hot rods and monkeyed around with Brit invasion elements until they got the rev and vrooom they needed. The goal was to create a sonic equivalent of teenage angst, raging lust and confusion. The Shadows Of Knight show us how it’s done with I’m Gonna Make You Mine and the Chocolate Watch Band make it a bit more explicit with Let’s Talk About Girls.

The Brits had taken American blues and morphed it into their own patented Limey blend. American teenagers would reverse this by retrofitting the Brit invasion sound, stripping it down, chopping and channelling it until it became the genuine punky, in-your-face American article.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Garage band rock was pretty much a DIY affair: you could go down to your local music store and gear up. Guitars were cheap, so pick up an axe, whatever new gadget or sound effects were on offer and that, plus a few chords and a bratty attitude, was all you needed. And these raging hormonal beasts could peel out of the garage, burning rubber in their custom-tooled sonic hot rods. Gentlemen, start your engines: the Blues Magoos’ (We Ain’t Got) Nothin’ Yet, Paul Revere & The Raiders’ Just Like Me and Baby Please Don’t Go by the Amboy Dukes.

For the most part, garage bands built their monster machines on chordal licks, the kind The Kinks used on You Really Got Me. They laid down a bed of chords, not in support of the melody but instead of it. This created ferocious energy and an unstoppable momentum, the sonic equivalent of the frustration, arrogance and raging lust that seethed in the adolescent American brain. Hendrix would turn that into heavy metal and in the late 60s, Keith Richards would use it to propel the Stones Mach II. Cue: You Must Be A Witch by the Lollipop Shoppe, Little Girl by the Syndicate Of Sound and the Count Five’s Psychotic Reaction.

When asked to define psychedelic music, Roky Erickson of the 13th Floor Elevators, replied: “It’s where the pyramid meets the eye, man,” referring to the Eye Of Providence, the spooky, ancient, alien-type image on the back of the dollar bill.

And who would deny that psych rock has a serious dose of alien DNA? Psych is an oxymoronic concoction, the fusion of two seemingly incompatible strains of rock – a pounding rock beat mated with an ethereal melody, trippy sound effects or lilting lyrics floating over the top. But the freaky combo worked spectacularly, as on the psych classic I Had Too Much to Dream (Last Night) by the Electric Prunes, where a spacey, ethereal opening lyric is followed by a relentless hard rock track. It also has going for it another psych rock ingredient: a bizarre sound effect. While rewinding the tape, the band heard this weird, oscillating reversed guitar sound and they just stuck it on the beginning of the song. It was the pre-Pet Sounds Brian Wilson who came up with the original template for psych rock by grafting the creamy harmonies of the Four Freshman onto Chuck Berry’s turbocharged V8 engine.

The next phase of psych was the San Francisco groups who were your basic psychedelic garage bands, such as The Charlatans. But while groups like the Grateful Dead were moving into interminable, spacey, music-of-the-spheres jams, garage bands took the three-minute single as their art form and stuck to the basic pop song structure, introducing the psychedelic elements in guitar breaks, electronic effects and freaky lyrics. These additions were unusually acceptable at the time because this was all happening around the high point of free jazz. You could mess with the rhythm, distort the melody, tweak the notes or play the notes between the notes – you could make any sound imaginable and then bring it back to the pop music format.

British invasion bands began exporting psychedelia, which expanded the palette of available sounds in rock. When Jeff Beck’s mock sitar fuzz-tone guitar on Heart Full Of Soul entered the equation, garage bands adopted mind-melting effects, the freakier the better – distortion feedback, speeding up the tape, backwards tape, phased guitars, wah-wah pedals, fuzz-tone, reverb units. You could spin stuff any way you wanted: the 13th Floor Elevators incorporated an electric crock jug; the Chocolate Watch Band used sleigh bells.

When greasers and frat boys got their hands on LSD, it induced a kind of sonic schizophrenia in them. Their bastard child, psych rock, was a two-headed monster, the perfect mutant catalyst for hormonally raging teenage greasers and the unholy thoughts that careened through their acne-pocked heads. Cue: Voices Green And Purple by The Bees. It’s scary as hell, but calm down and go on a kozmik kruise with Roky Erickson – it’s perfectly safe, just “Buddy Holly reading the Tibetan Book Of The Dead” on Roller Coaster. Or take a Journey To The Center Of The Mind with the Amboy Dukes (Ted Nugent insists this is not a drug song, but if he isn’t high, his spacey guitar sounds like it’s taken something). Go to an acid wig-out party with the Blues Magoos on their freak-out version of Tobacco Road, and spin just about anything by The Sonics (but don’t drink the strychnine).

No group took freewheeling experimental rock further than Red Crayola (later Red Krayola), formed by art students in Houston, Texas in 1966. Their “free-form freak-outs” involving the Familiar Ugly collective of some 50 anonymous performers sorely tested the patience of reviewers and record company executives, and drove even its ardent admirers to distraction. “It’s a band that has no idea how to play its instruments,” Alex Lindhardt wrote in Pitchfork Media. “In fact, they don’t even know what instruments are, or if the guitarist has the ability to remain conscious long enough to play whatever it is a ‘note’ might be.”

But that reckless open-endedness was just the point, as Lenny Kaye wrote in his review of the reissue of Red Crayola’s Parable Of Arable Land: “‘Definitions define limit.’ I first read this aphorism of Mayo Thompson’s on the back of the debut Red Crayola album in 1967, and promptly adopted it as one of the guiding touchstones of my life.”

Some of the more far-out groups interpreted psychedelia as a form of seizure, like drug-induced mania or mock mental illness that takes hold of the singer. Not surprisingly, psychedelic garage bands produced their fair share of raving eccentrics, the prime specimen being the incomparable, demon-infested Roky Erickson himself. In 1969, Erickson was committed to the Rusk State Hospital For The Criminally Insane in Texas (to avoid a prison sentence by pleading insanity). Apparently his insanity was not entirely feigned because 10 years after Erickson’s 1972 release from Rusk State, he claimed that a Martian was inhabiting his body, and that due to his new alien status, he felt he was being persecuted psychically by foolish humans. He has since recovered and returned to performing.

Another deranged genius of garage rock is Rudy Martinez, aka Question Mark, as in ? & The Mysterians. Like his bandmates, Martinez was a migrant farm worker who was into surf rock, but unlike them, he was clearly unhinged, a veritable Tasmanian Devil in wraparound shades. Bizarrely, Meat Loaf was hired as Question Mark’s bodyguard/minder at the age of 19. His main duty was to prevent Question Mark from getting his hands on his ‘hobby’.

“Let’s just say,” Meat Loaf recalled, “that he had a lot of tubes of model airplane glue and no model airplanes. One night I heard strange noises coming from Question’s room. I unlocked the door and went in. He was prowling the room, uttering terrible curses at an unseen demon.”

But whatever else he was, he was a force of nature. It’s said that journalist Dave Marsh coined the word “punk” to describe the way Martinez delivered the Mysterians’ hit song, 96 Tears, with such intensity against a relentless funhouse organ track.

Wooly Bully by Sam The Sham And The Pharaohs was a game-changing song in more ways than one. It was an infectious Tex Mex dance number and the first million-selling American record in the wake of the British invasion. The lead singer, Sam the Sham (Domingo Samudio) was a Tex Mex ex‑carny who drove around in a 1952 Packard hearse with maroon velvet curtains. Just 19, he delivered the lyrics to Wooly Bully with ferocious zeal, hitting the words eccentrically as if they were so many billiard balls. He claimed it was about his cat – we’ll have to take his word for it since the lyrics are inscrutable: ‘Hatty told Matty… get someone to pull the wool with you.’ Today he’s a motivational speaker and poet.

By the end of the decade, rock had become overblown and self-conscious, and inevitably the garage rock model got infected with a fatal dose. In a no-man’s land between early-60s pop and late-60s psychedelia, these bands were mainly one-hit wonders recorded on two-track tape and not affiliated with any specific movement.

The appearance of Nuggets in 1972 brought them back to life and helped inspire new generations of punk and grunge rockers, as well as inspiring a Sargasso Sea of psych genres, dream pop, shoegazing stoner rock and mind‑boggling soundscape extravaganzas. Champions of the freaked three-minute song zinging at you over the airwaves, coming from anywhere around the USA: The Fleetwoods from Ohio; The Sonics from Tacoma, Washington; the Count Five from San Jose; the 13th Floor Elevators from Austin, Texas. They produced a hodgepodge of music, just talented people popping up out of nowhere with these kooky songs. They all emerged independently of each other because unlike the UK where bands converged on London, the USA was so spread out there was little chance of interaction.

If the perpetrators of garage band rock were forgotten and now can only hope to live on as cult bands treasured by hipsters and trainspotters, it was in part because as one-hit wonders they had no career development. All they had to show for it was that adenoidal howl, the great American yawp. This music was originally labelled punk and these bands were now called proto-punk because punk has become a designated historical era. But to hell with that: this was music made by punks, greasers, animal house frat boys, migrant workers and the arguably insane, all pursuing a gleeful why-the-hell-notness.

This new branding was in part due to the phenomenal success of the classic Brit bands who were now serious artists with impressive bodies of work. But the truth is that the garage bands’ legacy was in their example for future disoriented, confused, ostracised and raging youth, and they – the Ramones, Nirvana – got the message. Sullen, boastful, leering, mouthing off, acting out, jerking off, whining, snarling, howling… psych rockers were masters of pineal-gland rock, inciters of Cone Head freak-out parties.

Psych rock garage bands were the last holdout before rock became codified. The creations of garage band musicians were so honest, naïve and goofy that by their nature they represent the essence of the pounding heart of rock. They are a last bastion of authentic expression before we subsequently found ourselves in the United States Of Rock.Before, rock music had been eccentric, with idiosyncratic voices and characters emerging randomly and spontaneously out of nowhere. There was now a music canon, a template and matrix for rock – the uniform, the hair, the look, the attitude and the acceptable musical roots. A bizarre orthodoxy had replaced the ragtag, unruly, raging bull of rock.

But rock was never meant to be organised into anything, become operas, or get judged in Halls Of Fame. It’s a sputtering, tumescent hymn to getting laid, to making sure your howl in the night disturbs the sleep of the smug and self-righteous. Every one of these songs seems to be saying, “I pissed on this rock to let you know I was here, so listen up!”

David Dalton was a New York Times bestselling author, a founding editor of Rolling Stone, recipient of the Columbia School of Journalism Award, and winner of the Ralph J. Gleason Best Rock Book of the Year award for Faithfull. He was the author of twenty-four books, including biographies of James Dean, Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin, Sid Vicious, the Rolling Stones, and, in 2010 (with Tony Scherman), a critically acclaimed biography of Andy Warhol, Pop. Dalton was the co-author (with Jonathon Cott) of Get Back, the only book ever commissioned by the Beatles. David died in July 2022.