"When I started getting rolling it was considered charming or entertaining – or stupid – for girls to want to play music": a story of New York folk, punk, riot grrrl and beyond

From New York folk through 60s psych, soul, punk, riot grrrl and beyond: a history of the women who've have had an insurrectionary impact on rock’n’roll

“Joan is a kind of folk-singing vicar. A singing politician,” British folk artist Dana Gillespie said of Joan Baez in 1965. “She’s trying to change the world. We Shall Overcome is typical of the effort she is making to get her ideas across to people in songs. She is not interested in singing for singing’s sake.”

It could reasonably be argued that, historically, for female musicians, “singing for singing’s sake” has been a luxury they could not afford; there has generally been too much at stake for that. Hence the sense of burning purpose, the incendiary energy, that propels many of the best female artists, even – especially – when they’re singing quietly.

Classic female blues saw suffering and subjugation either presented starkly or sublimated. In many ways the baton of missionary zeal was passed on to the female folk singers of the 60s, of whom the mixed-race Baez – arch protestor and social justice warrior – was the first and most fierce. Not for nothing was she deemed emblematic of the burgeoning folk movement, with its attendant agenda to promote equality and peace. It saw her chosen to appear on a 1962 cover of Time magazine – a rare honour back then for a musician.

If Baez was the mouthpiece of the beatniks, then Joni Mitchell spoke for the next generation: the counterculture’s hippies. But she went beyond protest singing, towards an equally revolutionary mode of self-reflection that caught the global mood of existential disquiet as peace and love gave way to war and racial strife. By the end of the 60s, some of the most significant artists across the musical spectrum were women, from psychedelic rock (Grace Slick) to soul (Aretha Franklin) to a titan of psych-rock-soul, Janis Joplin.

Slick embodied the carefree hedonism of the era, all black eyeliner, heavy fringe and billowing sleeves, but this was insouciance with edge: she swore like a trucker, was chemically adventurous and sexually licentious, and was placed on the FBI blacklist after she conspired to spike President Nixon’s tea with LSD. Here was the poster girl for free love and drugs. What wasn’t to like? Or, as Vanity Fair wrote: “Every American female over the age of 14 wanted to be Grace.”

If young white America worshipped Slick, then young black America was in thrall to Aretha Franklin. In 1967, her (sub)version of Otis Redding’s Respect, with its newly interpolated ‘R.E.S.P.E.C.T.’ refrain, hit the top of the charts and turned her into a feminist champion. It reverberated thereafter as an anthem of both the women’s rights and the civil rights movements. Rolling Stone deemed it one of the top five greatest songs of all time.

Janis Joplin was a complex figure: a torch bearer for feminism who, paradoxically, as Mick Brown argued in The Telegraph, “was never adopted by the feminist movement of the day; nor did she adopt it herself. She certainly didn’t subscribe to the radical feminist orthodoxies of the superfluousness of men.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Joplin was a strong woman with fatal weaknesses – for drugs and drink – and an omnivorous appetite for women and men. Still, she has, for more than 50 years, been a totem for female omnipotence, her powerhouse vocals seemingly symbolic of an unearthly force.

“I might be going too fast,” she told a New York Times reporter in March 1969, when she was hooked on alcohol and heroin, a year before her untimely death aged just 27. “That’s what a doctor said. I don’t go back to him any more. Man, I’d rather have 10 years of superhypermost than live to be 70 by sitting in some goddam chair watching TV.”

These artists weren’t just commercially successful, they were also creatively liberated; even, in some instances, wholly autonomous. The likes of Joni Mitchell and her rival in the intense, elliptically poetic stakes, Laura Nyro, were instrumentally dexterous singer-songwriters who also had a hand in the production of their music.

Whereas Mitchell was born out of the folk movement, Nyro had one foot in R&B and pop. She began writing Brill Building-ish tunes that became hits for other artists (Wedding Bell Blues, covered by the 5th Dimension; Eli’s Comin’, by Three Dog Night; And When I Die, by Blood, Sweat &Tears) before her increasingly personal songs, on albums such as New York Tendaberry and Christmas And The Beads Of Sweat, became impossible to cover.

Although she never achieved the level of success she deserved, she was a trailblazer in the realms of florid artistry and emotional self-expression. But Nyro was too wilful to be tied to the idea of capturing the female experience at the end of a turbulent decade, or kowtowing to her audience’s political demands. As she wrote in the sleeve notes for Stoned Soul Picnic: The Best Of Laura Nyro (released in 1997, the year of her death): “I’m not interested in conventional limitations when it comes to my songwriting. I may bring a certain feminist perspective to my songwriting, because that’s how I see life… It’s about self-expression.”

Neither Mitchell nor Nyro – or, for that matter, Baez or Joplin – were aspiring members of any putative sisterhood. As Mitchell later reflected: “I always thought the women of song don’t get along, and I don’t know why that is. I had a hard time with Laura Nyro, and Joan Baez would have broken my leg if she could. Or at least that’s the way it felt as a person coming out [on to the music scene]. I never felt that same sense of competition from men.”

She added: “[Joplin] was very competitive with me, very insecure. She was the queen of rock’n’roll one year, and then Rolling Stone made me the queen of rock’n’roll, and she hated me after that.”

Nyro was an atypical 60s artist, eschewing hippie dress and mores – indeed her career is said to have stalled following a disastrous performance at 1967’s Monterey festival, which was more cabaret than countercultural. However, she did inspire Carole King to make the move from behind-the-scenes Brill Building composer to quintessential early-70s confessional singer-songwriter. King’s 1971 album Tapestry was a landmark of musical accomplishment and sweetly dishevelled self-expression.

Artistically, Mitchell dominated the early 70s with a series of increasingly sophisticated albums matched only by Neil Young and Bob Dylan. But there were signs of a different kind of female expression and empowerment. There was all-girl rock band Fanny in the US who didn’t amount to much commercially but about whom David Bowie said: “They were extraordinary… They’re as important as anybody else who’s ever been, ever; it just wasn’t their time.”

And in the UK arrived Detroit rocker Suzi Quatro who, with glam-era hits such as 48 Crash, Can The Can and Devil Gate Drive, became a huge star, offering glimmers, with her all-leather image, of the punk-rebel onslaught to come.

And then, in 1975-76, word spread to Britain of two fast-rising acts: all-female LA rockers The Runaways, and a new kind of androgynous rock poetess by the name of Patti Smith. Both were harbingers of a new openness towards women in rock. After those two motivating forces of nature came the deluge: The Slits, X-Ray Spex, Siouxsie Sioux, Blondie, Pauline Black’s Selecter, Chrissie Hynde’s Pretenders, Pauline Murray’s Penetration, Tina Weymouth of Talking Heads and more all emerged during punk’s art-quake. No one would doubt the seismic power of the Sex Pistols and The Clash, but suddenly it seemed as though a lot of the most significant work was being done by women.

Indeed the late-seventies was such a crucial period for women in rock that music historian Caroline Coon has argued that “before punk, women in rock music were virtually invisible; in contrast, it would be possible to write the whole history of punk music without mentioning any male bands at all”.

“I agree with that totally, yes,” Blondie’s Debbie Harry tells Classic Rock. It’s almost as though there is before and after 1975. There was an explosion, and afterwards the landscape afterwards looked quite different.

“Yeah,” Harry agrees. “The charts up to that time are totally reflective of that change. Actually, it didn’t really become super-obvious until the end of the seventies into the eighties. When I started getting rolling in 1973 it was sort of considered charming or entertaining – or stupid – for girls to want to play music.”

Harry felt a “shift in consciousness” during punk, after which women could “actively pursue a career in music”, although even then she experienced resistance.

“It was just a different era, a different way of thinking,” she recalls. “I was told quite bluntly to my face that women had no place in the music business.”

Harry sensed that her very presence was political, and accepts that she offered a new paradigm: she wasn’t a demure folkie, a sweet pop singer or a ferocious harpy. Rather, she was something completely different: subversively pretty, slyly glamorous. While The Slits and Poly Styrene were challenging notions of beauty, Harry offered a cartoonishly exaggerated version of the same.

“I’m not manly – I’m very feminine – but I have a sort of masculine idea of what is right for me and I go after things,” she ventures. “I have a strong sense of determination, and a sort of a stubborn streak. When somebody would say to me: ‘Oh, go back to singing cabaret,’ or something like that, I’d become infuriated.”

Around the time of punk, there was a sudden influx of female musicians, and yet at the time, someone like Chrissie Hynde could still feel isolated.

“There weren’t a lot of women in bands back then, but I didn’t care,” Hynde says. “The whole idea of rock at the time was really androgynous and irreverent, antiestablishment and renegade – all these things that I liked. I was too shy to play with guys because I was still a girl, and I never really thought that would happen. But then I thought fuck it, I’m doing this.”

Fanny, The Runaways et al might have seemed like false starts. But this time women in great numbers were being taken seriously.

“That was the thing about punk – it did wipe the slate clean,” Hynde notes. “A lot of people snuck into punk who thought it was never going to happen to them. I was twenty-four when punk was starting – I thought I was way past it at that point.”

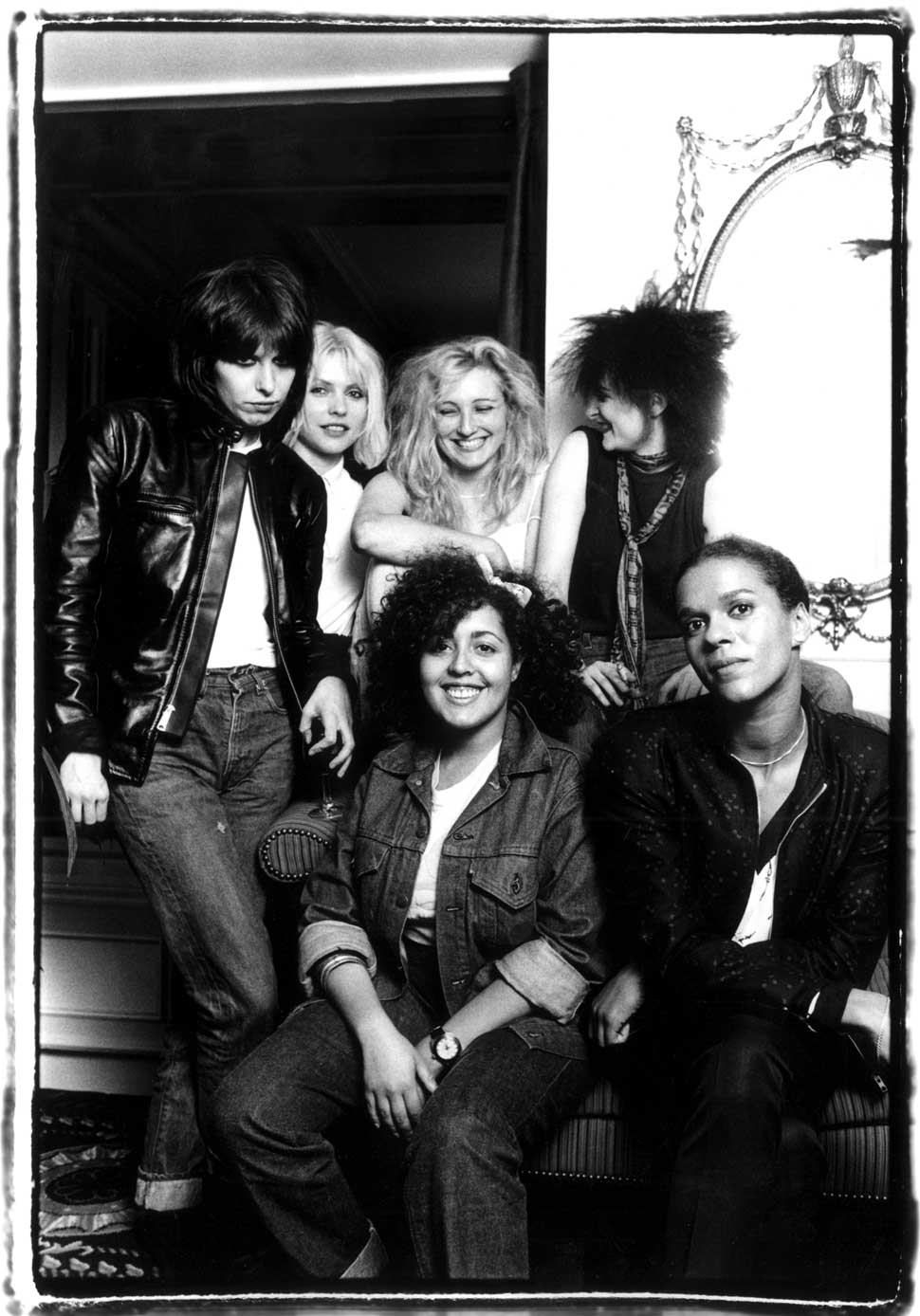

Far from it. Hynde’s Pretenders became one of the signal bands of the era. In 1980, to celebrate this golden moment for women in music, Debbie Harry arranged “a little tea party” – a summit meeting involving herself, Hynde, Viv Albertine of The Slits, Siouxsie Sioux, X-Ray Spex’s Poly Styrene and Pauline Black of ska band The Selecter. The encounter was immortalised with a photo shoot and a magazine front cover article.

“That was a statement of intent,” Black says. “Sort of: ‘We’ve arrived, and we’re not dressed in sequins and pearls.’”

Black felt a kinship with Styrene, like her being of mixed race, and especially liberated given the limited choices black female musicians were given at the time. “Black female performers were supposed to wear spandex or look like the women from Chic, or like Diana Ross,” she said. “The sexuality couldn’t be removed from the music they made, therefore they had to look sexually available. Punk and post-punk turned that image on its head.”

Black had grown up loving Dylan and Baez, who “talked about politics on a macro level”, and also Mitchell, who explored “politics from a female point of view”. Other crucial influences were Billie Holiday’s devastating Strange Fruit, the video for Aretha’s Respect (“A pivotal point for me as a black female”) and the sleeve to Patti Smith’s Horses.

Pauline Murray was the singer with County Durham’s Penetration. One of the bands who signalled the segue from punk to post-punk, they offered an oblique take on the Class Of 1976’s garageland laments. Murray had a similarly broad musical education to Black, acknowledging a debt to Kiki Dee and Vinegar Joe’s Elkie Brooks, and admitting that Grace Slick “would have been the sort of revolutionary person I’d have liked, but I was a bit young”.

Patti Smith was the first female rocker to impact on Murray in real time. Then she saw the Pistols. “They had that attitude where they didn’t give a shit, and that was very liberating,” she says. She promptly cut her hair, dyed it black and dressed “punkily”. She enjoyed the alienation effect. “That alone separated you off from the rest of society. It wasn’t necessarily not done as a political act, but it did get a reaction. People thought punks were disgusting, a threat to society.”

Punks, especially punk females, rejected pulchritude: “You weren’t making yourself look pretty, you were making yourself look pretty horrible. Poly Styrene with her braces, and The Slits – it wasn’t about looking nice for men.”

Their concerns were equally urgent: a noise-pop anthem such as Don’t Dictate was directed at Murray’s parents, but had “a wider implication”, while Silent Community addressed her “small-minded” North-East locale. Punk gave women like her a way out. “It was a life-changer for a lot of people,” she contends. “I was working in an office. My life would have been a different scenario without punk.”

Ater punk, music was never the same again. Female musicians were a given, not a rarity. That’s not to say there wasn’t a need for a galvanising movement such as riot grrrl. In the 90s it saw acts both British (notably Huggy Bear) and American (Bratmobile, Babes In Toyland) creating a space in which sexism and patriarchy, among other issues, could be explored safely. Although some nominally riot grrrl bands, from Hole to Sleater-Kinney, achieved a degree of commercial acceptance, it wasn’t as impactful on the mainstream as punk was.

Pauline Murray dismisses riot grrrl as “a bunch of privileged, white, middle-class rich girls… They weren’t as shocking as The Slits.” Possibly its impact was diluted because it appeared to have taken place on the margins. Besides, by then much of the work had already been done. As Murray says, the world’s biggest star, Madonna, was female – one, as Murray also points out, “who had been influenced by punk”, no less.

In fact many of the world’s biggest stars continue to be women (Taylor Swift, Beyoncé, Lady Gaga, Rihanna, Billie Eilish). More importantly, much of the most interesting music – from Svalbard to St. Vincent – is being sung, written, performed and produced by women, across all genres, from folk to metal. And they owe a huge debt to their forebears, who enabled them to create and exist not as a subset, but on equal terms.

“I never really felt like a female in rock,” Pauline Murray says, “I felt like a person in a band. That’s what was political about punk. It allowed women to just be people, not male or female. We were doing it like the guys were doing it. It was revolutionary."

Paul Lester is the editor of Record Collector. He began freelancing for Melody Maker in the late 80s, and was later made Features Editor. He was a member of the team that launched Uncut Magazine, where he became Deputy Editor. In 2006 he went freelance again and has written for The Guardian, The Times, the Sunday Times, the Telegraph, Classic Rock, Q and the Jewish Chronicle. He has also written books on Oasis, Blur, Pulp, Bjork, The Verve, Gang Of Four, Wire, Lady Gaga, Robbie Williams, the Spice Girls, and Pink.