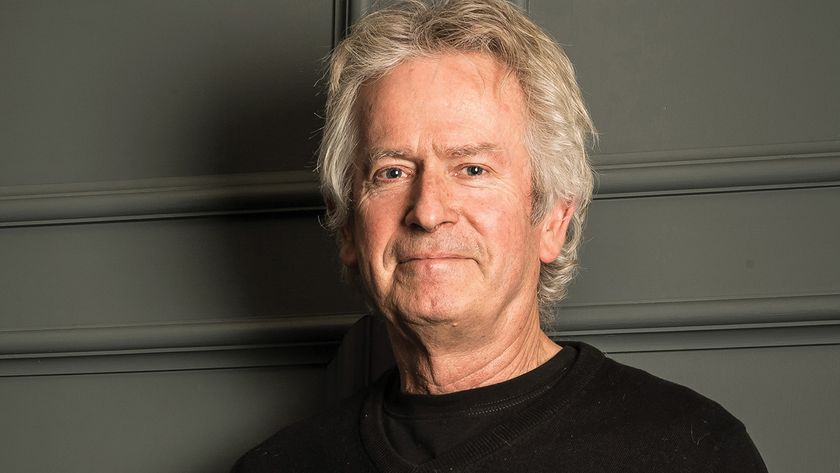

Dave Gahan was once the very picture of cherubic innocence. Back in the early 80s, Depeche Mode were purveyors of bubbly synth-pop, but as the Essex boys’ music got heavier and more industrial, Gahan’s image got rockier and his lifestyle darker.

By the mid-90s he had attempted suicide and overdosed on a speedball at LA’s Sunset Marquis hotel, his heart stopping for two minutes.

Today, living in New York and newly healthy after having a tumour removed from his bladder in 2009, Gahan is both a true survivor and an unlikely influence on a generation of rock bands. The 53-year-old singer has now teamed up with British duo Soulsavers for a brooding new album, Angels & Ghosts, which he discusses in an accent that’s equal parts Basildon and Brooklyn.

How far are you reaching back for inspiration on Angels & Ghosts? The lyrics suggest a degree of residual torment from your black period.

Now you put it like that, it does sound a bit grim! There’s definitely a lot of reflection when I start writing. I’ve been on this mortal coil for 50-plus years, and you start to have quite a lot to draw on.

Do you shudder at some of the memories? Are they still vivid?

They can be. Music draws that to the forefront. It happened with the Soulsavers record, it kicked up some old stuff. But I wouldn’t say it’s dark. To me, there’s hopefulness inside that darkness. I’ve been through a lot health-wise, but I’m in a good place right now.

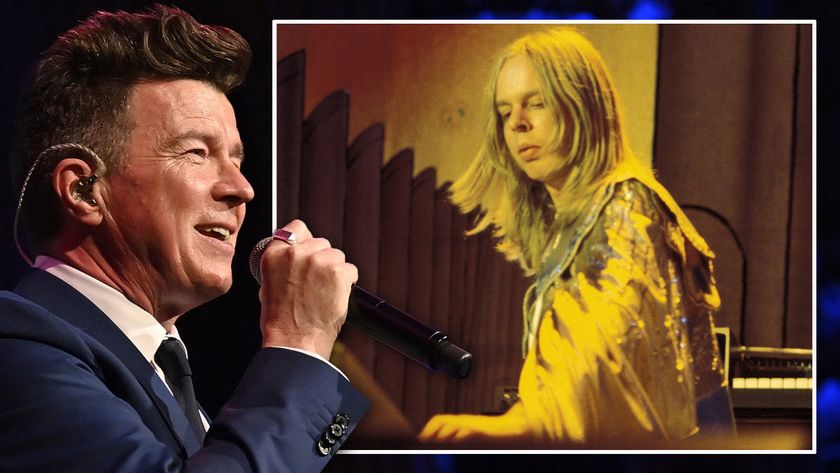

Critics talk about the radical change between the early you and the hirsute rocker version, but it was more gradual than that, wasn’t it?

You’re right. Even as a teenager that stuff was with me, and getting into Depeche has allowed me to let it out. God knows what I’d have done if I didn’t find that outlet.

Who was more into change: you with your hair and tattoos, or your bandmate Martin Gore with his chains and leather skirts?

That’s interesting – I think we were both doing it. We were pushing against this idea of what we felt we were being painted as.

What was the band’s reaction when you turned up looking like a Hells Angel?

When I showed up at the sessions for [1993’s] Songs Of Faith And Devotion, the look on everybody’s face was more or less shock. We hadn’t seen each other for a couple of years and I had this feeling of ‘Wow, this is going to be different’. And it was.

How strategic was your decision to take drugs and immerse yourself in that world in terms of upping your credibility?

It was completely strategic. It’s just that once I got in there it wasn’t as easy to get out as I thought it would be. We were always the band that wanted to go out and party and do things to the extreme. But once I took the reins off and allowed myself to go wherever it was going to take me, that was it, really. I can be very destructive.

Which was the most frightening: the heart attack, the suicide attempt or dying for two minutes?

None of them, really. They’re par for the course. There were things that were much more dangerous. I found myself in places in East LA that you’re just not supposed to be…

Do you think the new Soulsavers album sounds more like the work of someone who used to wander round East LA brandishing a handgun, or like the work of someone who used to steal cars and got chased by police around Basildon?

[Laughs] Well, it’s both the same. It’s all wrapped up in fear. The Basildon years were terrifying.

You were quite a hooligan, weren’t you?

Well, yeah, but there was nothing to do there. And so you get in with a certain crowd and that’s what you end up doing. Thank God things are different for my kids.

How do you rebel against a dad covered in tattoos bearing track marks from heroin?

My kids? Thank god they’re a lot smarter than I was. But at the same time they’ve got to live their own lives.

Do they know about the ‘gooch’, the scrotal piercing you had a few years ago?

Unfortunately, yeah. Not so much my [16-year-old] daughter, but my sons [23 and 28], yeah.

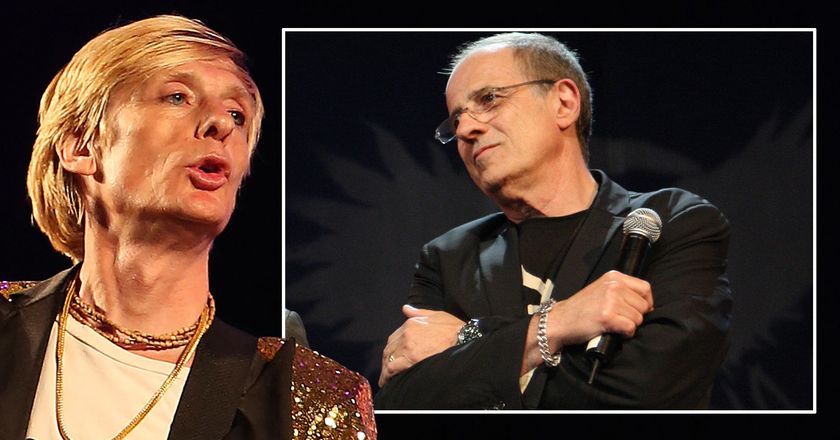

Did you see the recent article in Rolling Stone citing DM’s impact on Manson, Deftones, Rammstein and others?

Yeah. I think that comes from the so-called darker side of what we do. We took our music to a place that wasn’t the standard pop formula. We also happened to have great people working with us. Left to our own devices, we’d all be down the pub.

Who are your peers: New Order and The Cure, or Metallica and Guns N’ Roses?

New Order and The Cure. Growing up, Martin and I would listen to Joy Division, the Bunnymen, early Simple Minds – post-punk. I don’t feel like we had anything in common with Metallica or Guns N’ Roses, apart from going out performing and building an audience, an army that stuck with us. A lot of the other bands didn’t do that.

Isn’t your metamorphosis so complete that it would make sense to have other rock bands as peers?

Yes, it would, and that’s the highest respect, when you’ve got other artists saying they’re influenced by what you do. I don’t think it’s just the music, though. One thing people have always disregarded about Depeche Mode is our strength and our survival. We were probably the band that were expected to not last. We carried on, we made music that we wanted to make, and we did it our way.