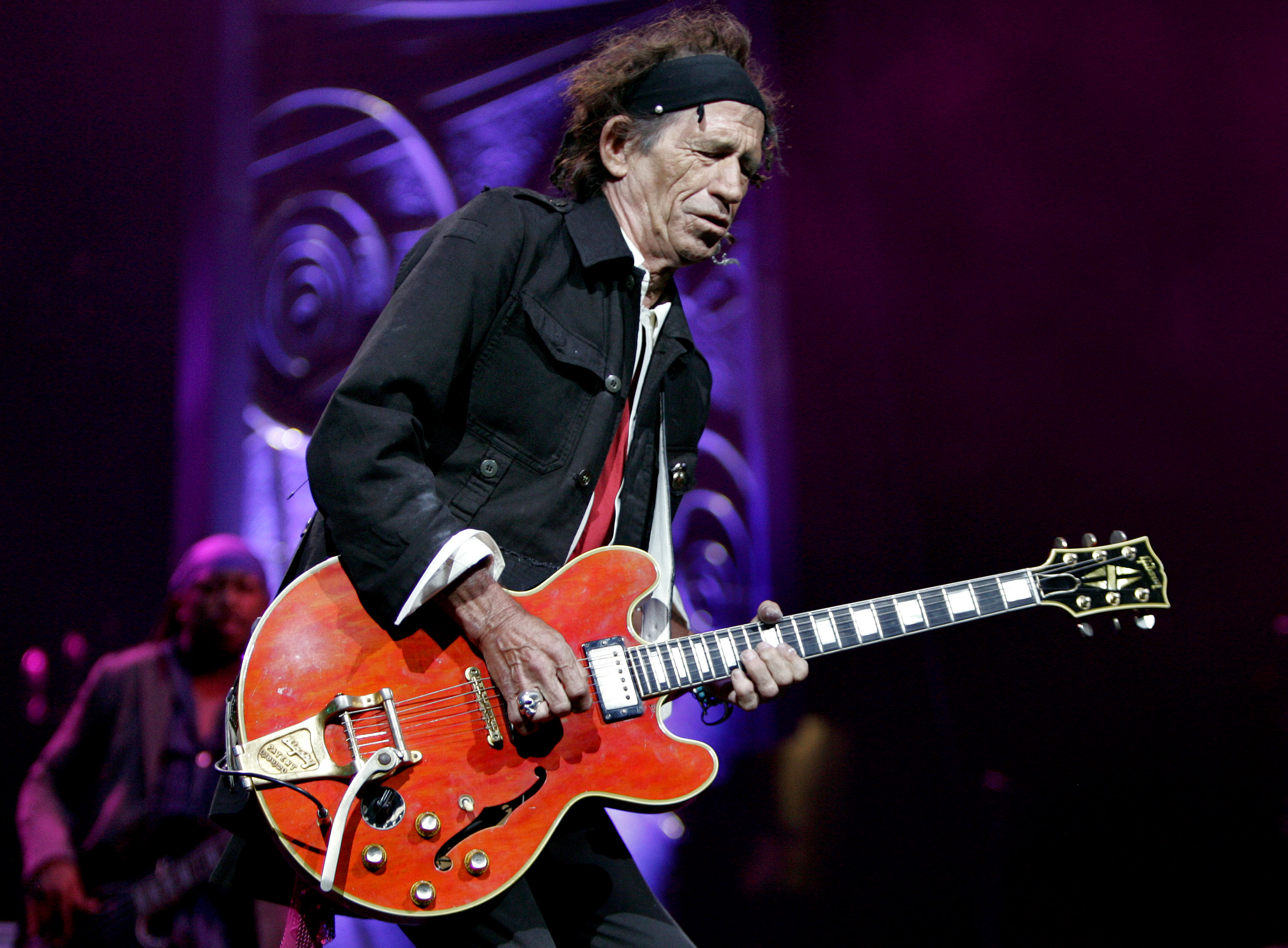

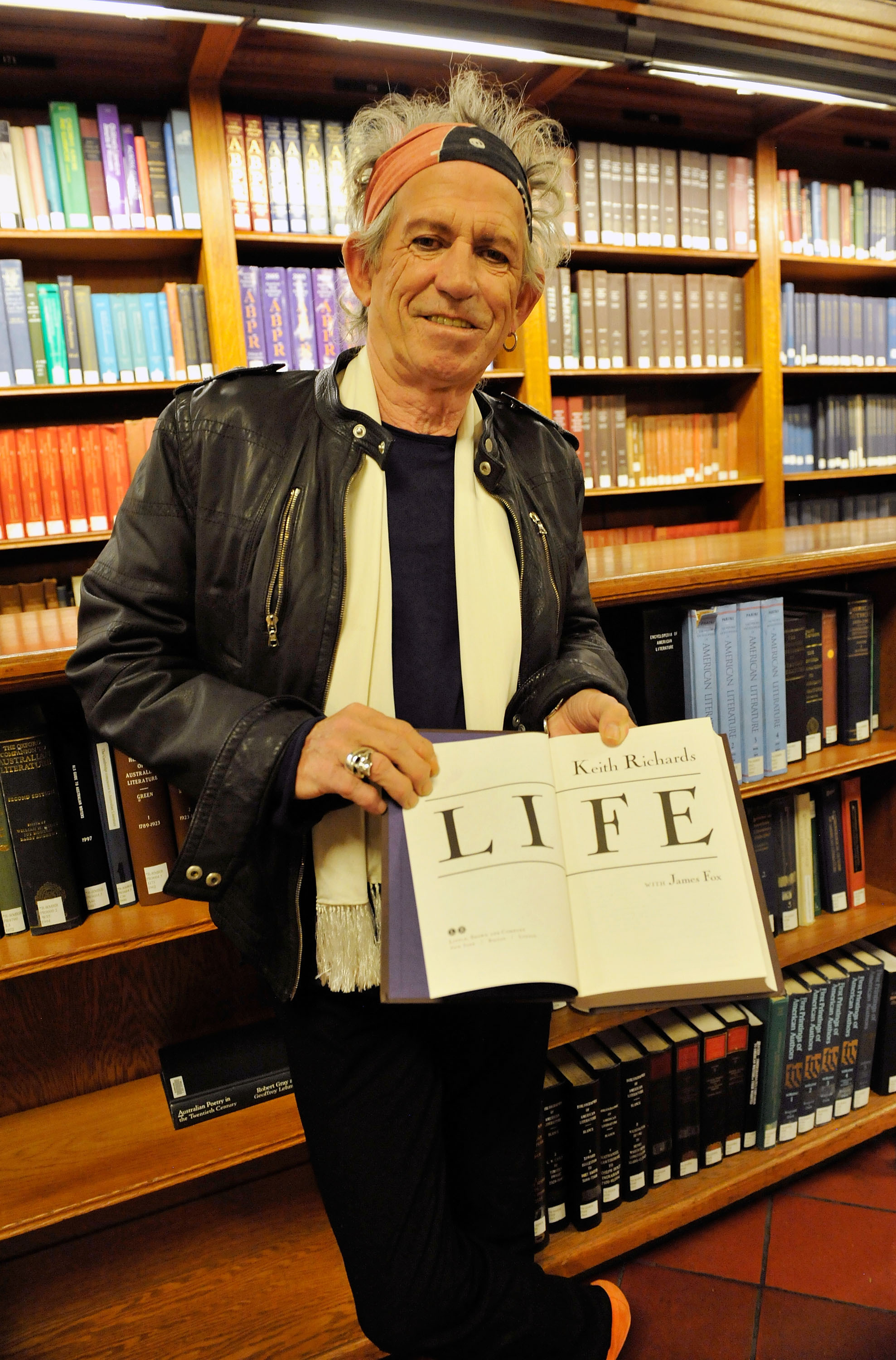

For the past few months, Keith Richards has been popping up everywhere: on TV, in newspapers and magazines, on the top of best-seller lists with his autobiography, Life, and probably among your Xmas presents. The busy schedule is nothing new for Keith, who has always managed to pack a lot in. As he says in his book: "For many years I slept, on average, twice a week. This means that I have been conscious for at least three lifetimes."

Last year Paul McCartney said that even at his age he can still sing his lungs out because he doesn’t question himself. Is that also your philosophy? To just go for it and make music without a safety net?

I couldn’t put it any better than Paul. I’ve never questioned myself. And even today I never ask myself whether I’m too old or whether I should still expect so much of my body. That doesn’t get you anywhere. You just keep doing it.

It’s interesting you bring up Paul, of all people, in connection with transience. I mean, he and Ringo are the last two living Beatles. I knew John well, also George and Ringo, but over all the decades Paul and I never really came together, never sat down and talked. We’ve only made up for that recently. It’s strange that it’s taken so many years. And it was really more by accident that it happened at all. For a while Paul was visiting me every day at my house on Parrot Cay [an island in the West Indies], where he also lives part of the time. We talked about song writing, life, death… and what distinguished The Beatles from the Stones.

And what was that?

Everyone in The Beatles could sing. We were more of a music band. We only had one frontman.

On McCartney’s last album he has a song about how he imagines his own funeral. Do you think about things like that?

No, I haven’t thought about my own funeral. I can understand why Paul would want to deal with such things but we’re very different in this respect. I find it difficult to tax my brain about the future. It wasn’t so long ago that I had a pretty concrete experience of death, when I fell out of a tree and injured my head.

You actually cracked your skull, which you didn’t realise at first, and then later had two strokes in your sleep as a result.

Yeah, it was a drastic situation. They had to surgically remove a blood clot from beneath the cranium. A lot of people around me thought I was going to die.

Were you scared?

What scared me was a letter from Tony Blair, who apart from his best wishes also wrote that I had always been his hero. The British head of state taking me, of all people, as a role model? That I found really scary.

Are you afraid of death?

There’ll be a great nothingness or… it will be the beginning of a whole new trip [laughs]. I only know one thing: if I meet the Devil, then God help him.

You now have four grown-up children. At some time most children rebel against their parents. How did yours rebel?

I don’t think they ever had any reason to rebel against me. I never made any strict rules about coping with life or dealing with everyday existence. We were nomads, constantly moving around. I’ve always made sure my children felt safe, but I didn’t have any rules. Who am I to make rules for my kids? I’ve been fighting against regimentation my whole life.

Have you warned your children about drugs?

We’ve spoken about it but I’ve never tried to lecture them. I’ve always looked at myself and my body as a kind of private property that I could experiment with, in the sense of “Oh, let’s take this stuff and see what it does to me”.

In your book you’ve written extensively about Mick Jagger, but the press has focused almost exclusively on the conflicts. Does that annoy you?

Affection doesn’t make for good headlines. Of course I knew that beforehand. I really don’t care. Mick and I are like brothers, not friends. And if two brothers are locked up in the same room for too long then sparks are going to fly. We often fought during the time when he had lead-singer syndrome and thought he was the greatest. I couldn’t and didn’t want to leave all that out of the book, because otherwise it wouldn’t have been honest. Sure, there was often trouble, but in the end we always managed to come together again. The wounds heal quickly. The really heavy conflicts happened nearly thirty years ago.

In one passage you make fun of the giant inflatable penis that Mick Jagger played with on stage, while you reveal that his own penis is tiny. Did you think twice before telling this to the rest of the world?

Okay, there I’ve opened up some old wounds. That’s also part of my story. Otherwise I wouldn’t have been able to tell it honestly. I also know that I drove Mick crazy with my behaviour for years. Of course every one of those sorts of details now stands out. That’s why I gave Mick the book to read beforehand. He knew what was coming. He was prepared.

There wasn’t an argument as a result?

We’re looking forward to going on tour together next June. Does that answer your question?

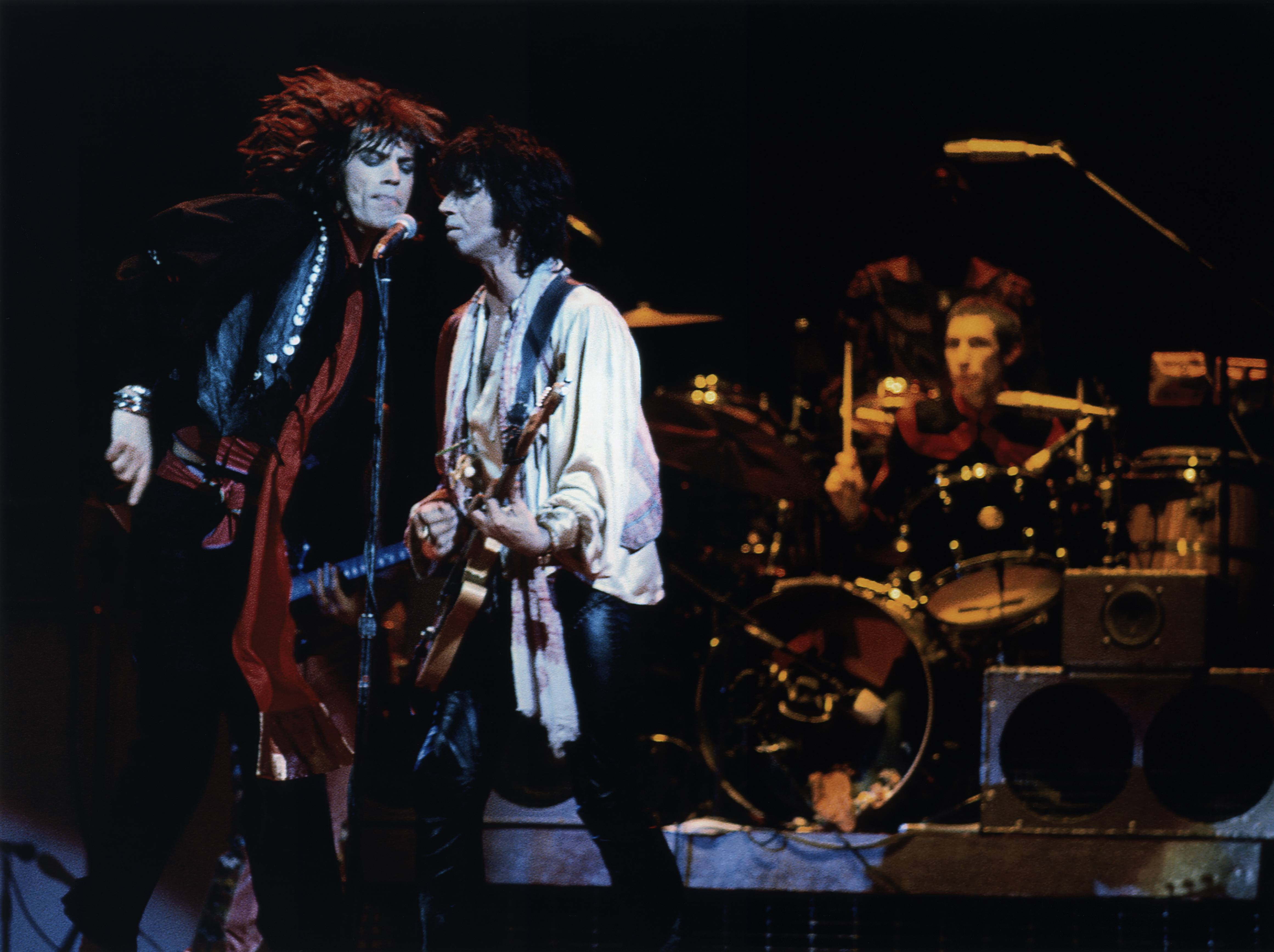

For more on the Stones early years and influences, then click on the link below.