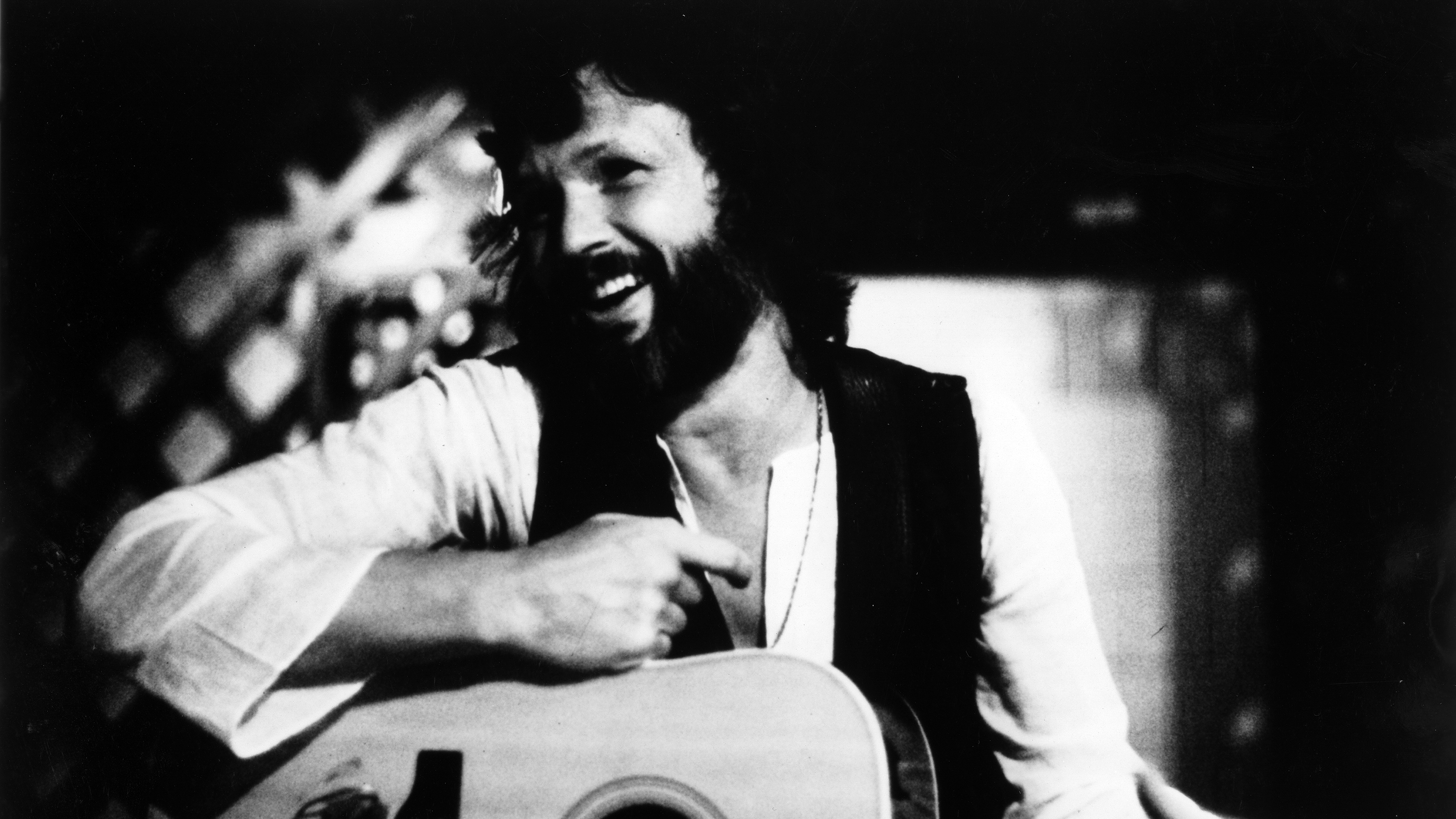

To call Kristoffer Kristofferson a country singer is faintly absurd. The man has lived several lives. He was a high-school sports star who got a scholarship to Oxford. He flew helicopters for the US army, and later worked on oil rigs. A late developer musically, he famously worked as a janitor at Columbia Studios in the mid-60s while writing songs in the daytime. He got his break in 1969 when his timeless road anthem Me And Bobby McGee was a radio hit for Roger Miller, which enabled Kristofferson to sign for Monument Records and kick-started a career that has embraced dozens of albums, and some notable movie roles including Pat Garrett & Billy The Kid and opposite Barbra Streisand in A Star Is Born.

What’s up in Hawaii?

Lots of nothing much. It’s heaven. I live in Maui, in a secluded place called Hana. I got no neighbours, and we live right by the beach. Paradise. I don’t have to do anything, except get on the tractor and mow my lawn. We got killer grass here – both types [laughs].

Talking of killer grass, how’s your old friend Willie Nelson?

Willie’s just been staying on the island. I saw him yesterday. His daughter Amy and Arlo Guthrie’s kid Cathy have got this ukulele band called Folk Uke – careful how you say that. Willie and me went to see ’em in a local club.

What are your memories of playing in the Highwaymen with Willie, Johnny Cash and Waylon Jennings?

Those tours and the records we made were a great time. I just wish I was more aware of how lucky I was to share a stage with those people. I had no idea that two of them would be done so soon. Hell, I was up there and I had all my heroes with me – these are guys whose ashtrays I used to clean. I’m kinda amazed I wasn’t more amazed.

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

You’re in your seventies. but you seem to be working harder than ever. You’ve got five films in production, including a Western, The Last Rites Of Ransom Pride, and you’re on the road again.

Yep. I don’t know what the secret to that is, because I feel like I’ve got less energy than ever. But I’m lucky to keep working and doing what I like to do.

Now you’re back in Europe, playing solo. Do you miss not having a crew?

No, because my tours would kill a normal man. I’ve been going out alone for ten years. I was in London filming and I got an offer to play a club, and since I couldn’t round up the troops, like Stephen Bruton, I took the solo plunge. Man, it was scary. And I’m still scared before the bell goes. Luckily audiences in Britain and Ireland are receptive. It gives me the chance to be a train wreck. I get through for some reason. Maybe people just want to hear my songs. They must know I’m never gonna be Ray Charles or Hank Williams as a vocalist.

We’re getting a lot of mileage out of your new album, Please Don’t Tell Me How The Story Ends.

Those old publishing demos? Those are okay. We dusted ‘em off, and it was a lot of fun hooking up with my old band members. Did you see Dennis Hopper sent me a telegram for the booklet? It reminded me of the good times we had when music was all that mattered. I’m a late developer, for sure, so I wasn’t cutting teeth. I’d had five years of intense songwriting and pitching in Nashville, trying to find singers who’d buy my stuff and publishers to finance ’em.

During the period ’68. to ’72. when those demos were made, you played the Isle of Wight festival in 1970. How was it?

It was a total disaster. I’d only ever played a few clubs – the Troubadours in LA and San Francisco, the Bottom Line and Kettle o’Fish in New York City. We paid our own way to come over, stayed in a crummy hotel on the island. And they just hated us. They hated everything. They booed us, Joni Mitchell, Joan Baez, Sly Stone; they threw shit at Jimi Hendrix. At the end of the night they were tearing down the outer walls, setting fire to the concessions, burning their tents, shouting obscenities. Peace and love it was not.

The Doors also played Isle of Wight that same year. Did you model John Norman Howard, the character you played in A Star Is Born, on Jim Morrison?

That’s a good idea but it’s not true. I don’t think I ever met Morrison. A lot of people said we looked alike – shirts off, beards – but that washed-up rock star [in the movie] was more about me.

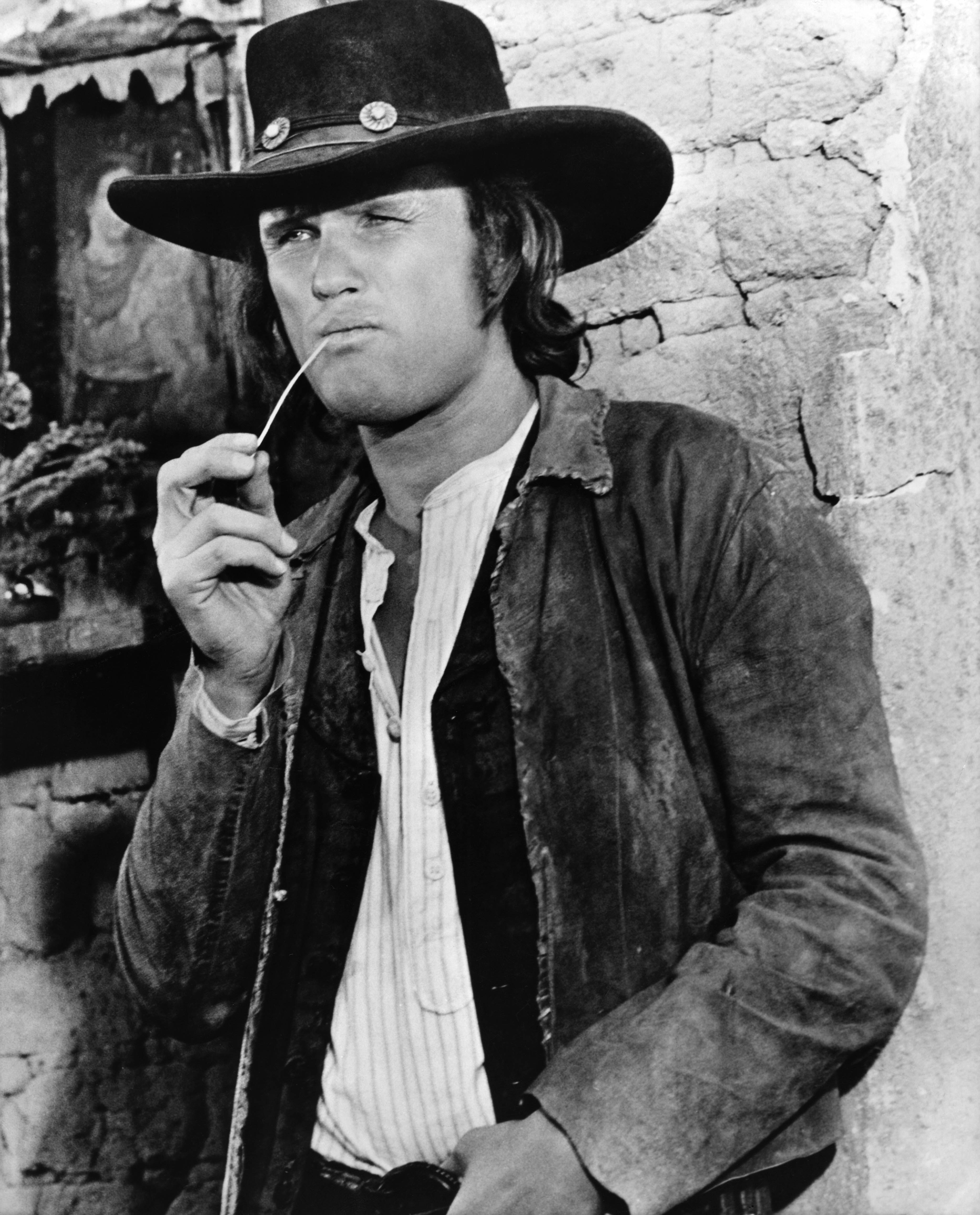

What was it like playing Billy The Kid in Sam Peckinpah’s 1973. classic Pat Garrett & Billy The Kid?

That was crazy. Peckinpah was apt to strange behaviour and moods. Bob Dylan was playing a character called Alias. We spent a lot of time chatting in our trailers and I told him about my friend Willie Nelson. I asked Bob: “Why isn’t Willie famous? He’s a genius.” So the next day Bob calls Willie up and gets him to come down to the set, and he made him play his old Martin guitar for ten hours straight. They ended up doing all these old Django Reinhardt tunes. It was fabulous.

Have you stayed friends with Dylan?

Tell the truth, although I know Bob we don’t hook up too often unless it’s on the road. I don’t want to get in his hair. Dylan’s got a million people who want a piece and I ain’t inclined to do that. Him and Cash were real tight. But I’m still in awe of Dylan, even now. Our generation owe him our artistic lives because he opened all the doors in Nashville when he did Blonde On Blonde and Nashville Skyline. The country scene was so conservative until he arrived. He brought in a whole new audience. He changed the way people thought about it – even the Grand Ol’ Opry was never the same again.

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #148.

Max Bell worked for the NME during the golden 70s era before running up and down London’s Fleet Street for The Times and all the other hot-metal dailies. A long stint at the Standard and mags like The Face and GQ kept him honest. Later, Record Collector and Classic Rock called.