“My songs are like Bic razors,” Freddie Mercury declared in Queen’s early days. “For fun, for modern consumption. You listen to it, like it, discard it. Disposable pop.” But 23 years after his death, his band’s latest album is called Queen Forever. And that band’s two remaining members, guitarist Brian May and drummer Roger Taylor, concede that for them the title is true.

“I understand people who say: ‘There is no Queen without Freddie. Just leave it be,’” Taylor admits, “because that’s what we felt, following his death. All three of us said: ‘Right, that’s the end of the band.’ But the band just didn’t seem to die.”

May now believes that trying to lay Queen to rest with its singer was doomed from the start. “Even though both Roger and I were adamant it was over, it never went away.”

The Queen machine has been cranked into its highest gear for almost a decade during the past 12 months. Queen Forever reworks three forgotten Mercury vocal tracks, alongside a collection of mostly neglected ballads, intended to reactivate interest in their catalogue’s deep backwaters. Queen were added to Classic Rock’s Roll Of Honour as Band Of The Year, after triumphant tours of the USA, Far East and Australia with new singer Adam Lambert. In the US especially, a relative wasteland for Queen since the 80s, Lambert’s flamboyant performances and solo stardom since contesting American Idol in 2009 (when he first performed with Queen) has helped raise them to new heights.

May and Taylor still have regular Queen band meetings. When they and Lambert speak to CR they are in the peculiar position of preparing to go back out on the road for Queen + Adam Lambert’s first full European tour, while curating their late singer’s legacy in Queen Forever. It’s an odd afterlife which began with 1995’s posthumously finished album with Mercury, Made In Heaven, continued with four tours and 2008’s now virtually disowned album with vocalist Paul Rodgers, The Cosmos Rocks, and shows no signs of ever stopping. Queen’s classic songs keep gaining new leases of life. But, as May and Taylor admit, they don’t expect anything they do now to equal their music with Mercury.

Brian May, sleepy after a trip to Paris, calls Classic Rock on the phone, as does Lambert. Taylor meets us in his home studio, a stone’s throw from the pub and golf club of a sleepy Surrey village. His mansion and the South Downs can both be glimpsed through the trees. Tracksuit-casual, his hair and beard white, Queen’s drummer is the most bluntly forthright about their future in 2015. And he can’t raise much enthusiasm for Queen Forever, for a start.

“I was very pleased we had three new tracks to put on it, which we laboured long and hard over,” he says. “As well as the Michael Jackson track There Must Be More To Life Than This, there is another song Freddie did with him called State of Shock [later recorded with the Jacksons and Mick Jagger], with a massive rock sound. But we could only have one track with Michael, which is a great shame. Let Me In Your Heart Again is absolutely typical mid-period Queen. And it was Brian’s idea to revisit Love Kills, which I feel works. But apart from that it is a rather odd mixture of our slower stuff. I didn’t want the double-album version they’ve put out. It’s an awful lot for people to take in, and it’s bloody miserable! I wouldn’t call it an album, either. It’s a compilation with three new tracks. It’s more of a record company confection. It’s not a full-blooded Queen album.”

“I can understand Roger’s reticence,” May laughs. “He’s not really a ballad writer, so this album’s not really representative of Roger Taylor. It actually wasn’t our idea. If it had been down to me it would have been an EP of these new songs, but we’d already promised the record company some kind of compilation.”

May still had strong feelings, hearing Mercury’s voice again on the rediscovered tapes. “There’s always a moment,” he says. “Particularly with Let Me In Your Heart Again. When I put the original tape on, it was so astonishingly real, like it had been recorded that morning. I got quite emotional about the way Freddie was doing his thing. It’s like suddenly coming across recordings of your parents after they’re gone. And then it turns into something rather joyful. In the old days I was often the one there at night anyway, trying to sort out takes that Freddie was all over. It feels comforting to be back in that situation. It’s almost like Freddie’s still around.”

Are these three tracks the last active part Freddie Mercury will play in Queen’s story?

“Well in a sense he’s always active, no matter what we’re doing,” May believes, “because I don’t think we can ever go out there without Freddie being a part of it. We’ve been on tour in the States with Adam Lambert, and Freddie’s already there because of the writing, and the original performances that we model the show on. But he’s there also in a much more tangible way, because we use video footage. It’s nice to feel he’s part of it, without being swamped by nostalgia. I think we tread that line quite tastefully and carefully.”

“There’s never going to be another, and I’m not replacing him,” Adam Lambert explains. “That’s not what I’m doing. I’m trying to keep the memory alive, and remind people how amazing he was, without imitating him. I’m trying to share with the audience how much he inspired me.”

Lambert’s youthful energy, vaulting vocal range and American stardom have revitalised the band in the US over the last year. Queen’s classic songs had already gained new audiences as they found their way into TV shows and films, from Bohemian Rhapsody in Wayne’s World to Somebody To Love in Glee.

“It’s massive there now,” May agrees. “What’s changed is, Adam is the first person we’ve encountered who can do all the Queen catalogue without blinking. He has that range, and that affinity for things on the edge of camp that Freddie had. You can see people at concerts looking a little reserved at the beginning: ‘Why are we looking at this guy from American Idol singing Queen songs?’ After about three songs, they go: ‘We get it!’ They laugh, they cry, and it’s a Queen show as much as it ever was. I don’t think Freddie would mind me saying that, or that I’m being disloyal to Freddie. Adam’s got that instrument, and goes for it.”

Many singers have stood in for Mercury since his death, from the blues-rocking Paul Rodgers to pop star Jessie J at the Olympics Closing Ceremony. But Lambert has one possible advantage over his predecessors: he is extravagantly gay, in a way Mercury chose to imply blatantly. This seems to give his performances an authentic connection to Mercury, which Queen have lacked since 1991.

“All I know is, his theatricality and flamboyance works with our music,” Taylor considers. “Some of which is very theatrical and almost overblown, very big. He makes no bones about his theatricality, and he’s on stage as an openly gay man – there’s no pretence. So yeah, maybe!”

“It’s a funny question,” says May. “But sometimes I find my mind wandering down those paths as well, because so many of the greatest musicians have been gay. I wonder if there is a special kind of magic that appeals to girls as much or even more than boys. There’s a kind of mystery there. But we’re very at home with it, and sexuality has never been an issue in any sense. Although people think of Adam as being from American Idol, he actually comes from a theatrical background. That’s another connection, because Freddie was very theatrically based too.”

“I think maybe to some people it helps them understand me better,” Lambert offers. “Maybe it creates a framework to understand my sense of humour, or put me into a category that’s similar to Freddie. So yeah, it might give people a certain amount of permission to enjoy it, because it’s drawing comparisons to somebody that they know is accepted. I don’t think being gay is taboo at all now. People have moved on from that.”

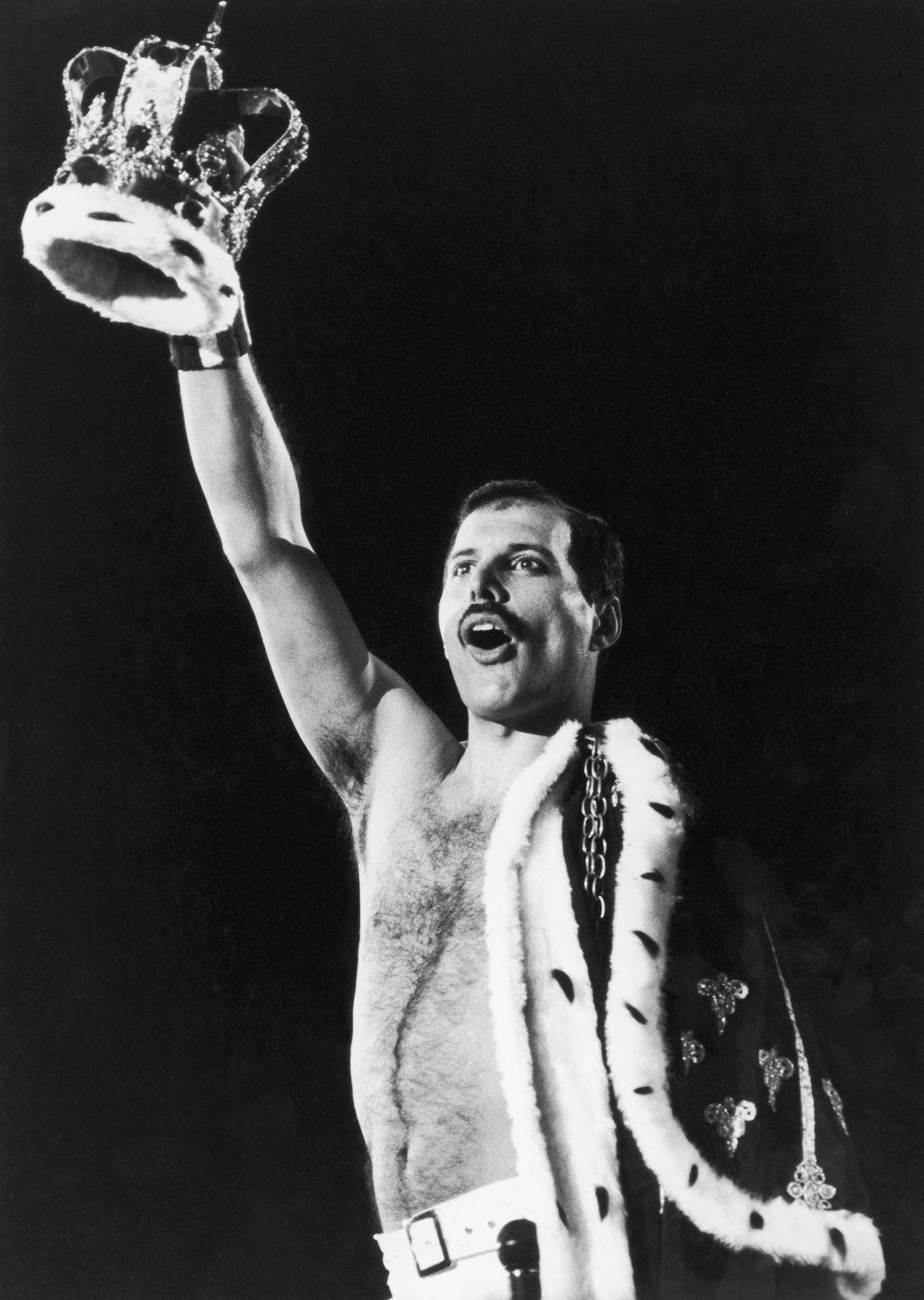

That certainly wasn’t the case when Mercury changed his image with 1980’s The Game album and tour: from the long-haired rocker of the band’s early days to a moustachioed, more explicitly gay look. The Game was Queen’s last US hit album.

“In America Freddie’s sexuality definitely hurt us,” Taylor admits. “We had people throwing disposable razors on stage when the moustache appeared, which was obviously a very iconic gay look at the time. And [in 1984] MTV wouldn’t play I Want To Break Free, when we were all dressed in drag. It was a very narrow-minded station then. It just seemed to be all fucking Whitesnake…”

May says Lambert is “a gift from God”, and the only reason Queen are playing now. Taylor describes his voice as “one in a billion”. Their mutual respect has raised the prospect of brand new Queen music. But after The Cosmos Rocks Queen’s veteran pair are wary of going down that route again. When I spoke to Paul Rodgers in 2014 he made clear his own unhappiness at the experience. “Politically, Brian and Roger were calling the shots,” he recalled. “We’d done some amazing shows, and Roger had some hip, cool songs, but it could have been better.”

“I guess, yeah,” Taylor considers. “I had a lot to do with that album. It was made in this room, actually. It had some great stuff on it. I just think that Paul’s more blues and soul – one of our favourite singers, ever – but when it boils down to it he wasn’t the perfect frontman for us. I felt the album was badly promoted by EMI, who were falling to bits at the time. We were on tour in Europe, and I went into record stores and we weren’t in them. And I remember being furious, thinking: ‘Why did we make this fucking record?’

“It certainly made us think twice about making a Queen album with another singer,” he adds. “There’s a resistance among the record-buying public to that idea, because Freddie was so inextricably linked with us. When you lose the brand, people aren’t interested. That’s why even Freddie’s solo albums, or Mick Jagger’s, or certainly mine, aren’t going to break any sales records. People want the brand. It’s a horrible word, but very apt.”

“I wouldn’t be averse to recording again,” May considers, “but we haven’t discussed it. And we spent a huge amount of time making that album with Paul Rodgers, going through quite a lot of pain, and I don’t think it made the slightest dent on public consciousness. So I would be cautious about being in a recording group called Queen without Freddie. Maybe we should be doing something else with Adam. Maybe we should be part of his recording future.”

Lambert, with a third solo album to finish and a successful solo career to resume once this tour is done, is also politely noncommittal. “I’m so honoured to be performing with the group,” he says. “It’s a limited engagement, a once-in-a-lifetime thing. Getting in the studio and creating new music and calling ourselves Queen is a different situation.”

“I’ll say one thing,” Taylor states. “If we have the material, then I wouldn’t go into making a record with any other singer than Adam, because he is so perfect with Queen. He has the range and the talent. I certainly wouldn’t be averse to giving it a go.”

Taylor knows, though, that he and May will never have as strong a collaborator as Mercury again. With bassist John Deacon retired since 1997, the duo are Queen, and anyone else they work with isn’t.

“You’re right, of course,” Taylor concurs. “With Freddie we were all contemporaries. I don’t think there’ll ever be anybody who will come into our group like that. But we very much respect Adam’s ideas. He’s incredibly musical, and we’d certainly take anything that he said quite seriously.”

Does Mercury’s loss, though, necessarily weaken any music Queen make in the future?

“Well, you’re missing your best and prime songwriter,” Taylor says. “We could all write songs, but Freddie was born to it. He constantly surprised us. I still don’t know where some of his lyrics came from, they’re so clever, almost Cole Porter-ish at times. Or like when he was writing all that slightly Tolkien-esque, proggy stuff. I never saw Freddie read a book, but he must have been a great black hole of information. That’s why Brian and I haven’t made more new music since he died, because we know we wouldn’t bring the full arsenal that we had to the table. I have a deep suspicion Adam would fill some of that gap, but we haven’t actually written anything with him yet. We haven’t even discussed it between ourselves.”

Taylor believes that he and May have lost some of the creative tension that left such productive blood on the studio floor in the 70s and 80s. “It’s not the same as when there were four of us all pulling in different directions. We know each other too well, so we skirt around each other a bit. We know our strengths, so there’s a tacit agreement on things.”

Their musical extremes, too, have gone. “Part of Freddie’s thing was to say: ‘Too far’s not far enough!’” recalls Taylor. “We used to like to stretch the boundaries in Queen if we could. But I don’t think we stretch boundaries any more. We’re good at what we do. We’re prisoners of our own making, I suppose. It’s not a bad prison.”

“We haven’t really recorded together for so long, I don’t know how it would be now,” says May. “Queen was a fight all the way along the line, sometimes quite destructively, and out of it all came a great strength. Roger and I still disagree about almost everything in the universe, but I think we’ve grown up some. We know when it’s time to back off, though that’s hard for us both. It’s like brothers, I suppose. We still have our moments on email. Things get quite ugly there, generally about music, arguing over the smallest parts. Which I suppose shows that we still care.”

As May and Taylor ready themselves for yet another stadium blitz, decades after they thought they were done, do they see any natural end to Queen? Or has the music they made as young men become a job for life?

“Oh, definitely,” Taylor says. “There comes a point where you realise: ‘Don’t think about the next thing, because this is what you do – this is what you are.’ We are inextricably linked to this music. And I love making a racket in a big loud rock band. As long as we’re fit I don’t see any reason to stop.”

“For the first half of Queen,” May remembers, “we thought: ‘I’m doing this now, but the rest of my life might be something different.’ But this is what I have done with my life. I have been an artist, guitar player, writer, producer… and I’m proud of that.

“I’ve also become a more balanced human being than when we were rock stars touring nine months of the year and recording for three,” he adds. “I’ve let other things I was neglecting back into my life. I spend time now working on defending animals, and with astronomy and stereoscopy [a Victorian form of 3D]. But when Queen calls, everything else takes a back seat.

“I think it still works because we don’t need to do it, but we have a desire to do great things. That’s never gone away. Like when I played on the roof of Buckingham Palace [for the Golden Jubilee in 2002]. Freddie was nowhere near it, of course, but it was part of the same desire to make fabulous things happen. And we couldn’t do these gigs with Adam if they didn’t still excite us.”

“Brian’s involved in so many other things, and he’s protecting every kind of furry animal; nothing for the insects yet,” Taylor laughs. “And I love boating, and doing a bit of shooting, where I’ve got a completely different set of friends. So the diary’s full anyway. But it’s that old-fashioned thing about security, and not being useless. I’d rather graft than go out to grass. But you do need a great frontman. And you need a full arena. Otherwise, forget it. If we felt we were struggling, that people were putting up with us, I wouldn’t do it. I would hate for us to just fizzle out. That would be the end, wouldn’t it?”** **

Queen + Adam Lambert begin their UK tour on January 13.