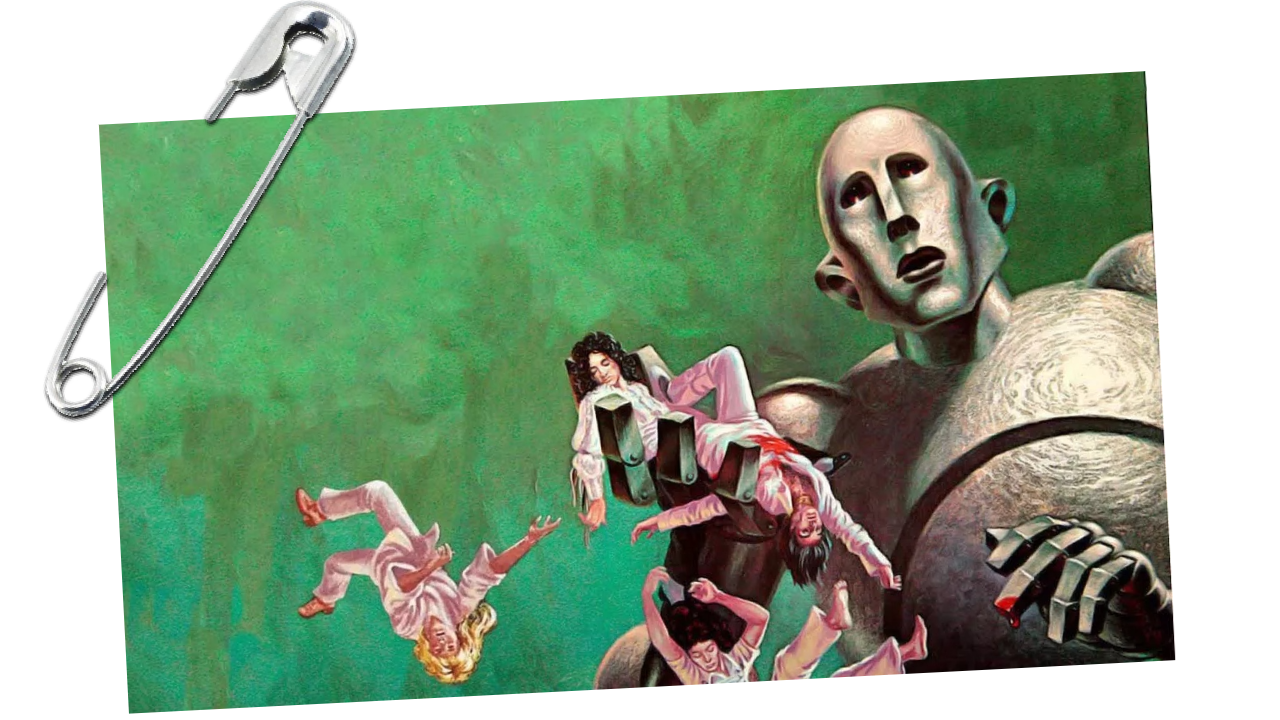

Friday, October 28, 1977. It should have been the day that marked the end of Queen’s reign. The future of their sixth studio album, News Of The World, released that day, looked bleak at best. A year before, their previous album, A Day At The Races, had received such a critical battering that Freddie Mercury’s days of bringing opera to the masses, darling, now seemed decidedly numbered.

A Day At The Races, the follow-up to A Night At The Opera – their Bo Rap-containing 1975 breakthrough international hit – was considered flaccid by comparison. The moment where the group’s desire to push the musical envelope crumbled into self-indulgent parody. The worst accusation of all: that Queen in the studio had begun to tread water; that having found the magic formula for success they now simply joined the dots and offered up the same again – only not different.

At a time when punk rock was considered the new critical yardstick, Queen suddenly epitomised everything about the old rock aristocracy that was now held in contempt: massive production, back-arching guitars and the once glorious, now oddly out of step image of Freddie Mercury preening in front of the audience, wishing them all “champagne for breakfast”.

As if to ram the point home, on the very same day that News Of The World was released came Never Mind The Bollocks… Here’s The Sex Pistols. The vast gulf between what was now regarded as the spiky, blades-drawn future and the flatulent, fairy-dust past was thrown into even sharper relief when one compared Johnny Rotten’s God Save The Queen with Queen’s own bombastic version of the national anthem which still closed their shows.

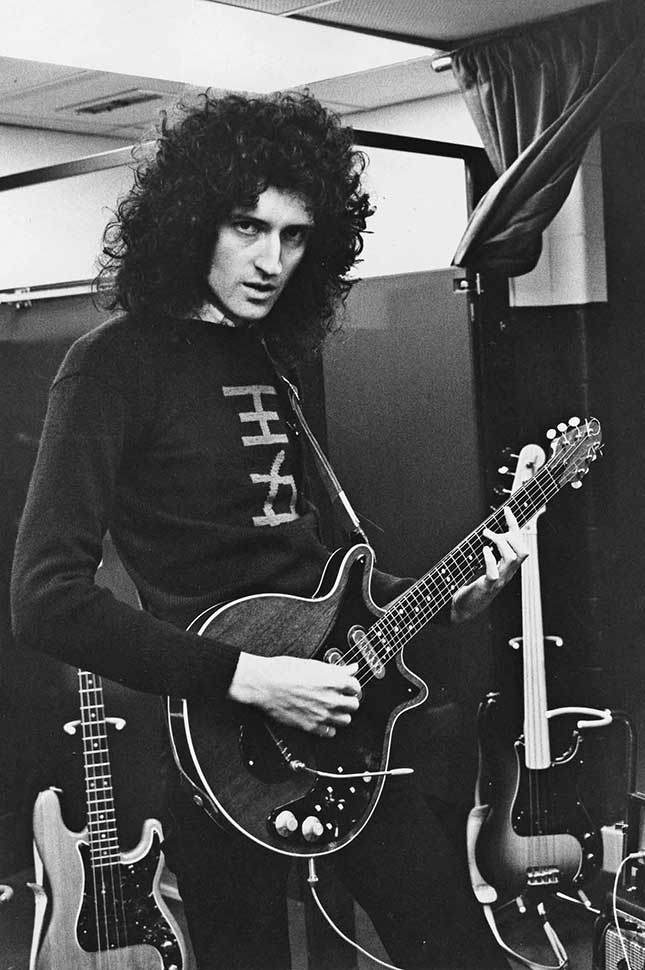

Speaking with me some years later, Brian May – the former PhD student studying Motions Of Interplanetary Dust, who’d fashioned his favourite guitar out of a fireplace, which he played with an old sixpenny piece for a plectrum – insisted that the band had remained impressively unmoved by such accusations.

“The most popular misconception of people outside the people who ‘get it’, as you would say, is that Freddie took himself seriously," said Brian. "They didn’t understand that although he took his work incredibly seriously, there was always that element of self-parody, if you like, in Freddie. He was always slightly tongue-in-cheek, there was always a little twinkle in his eye. And I think that’s what was missed by the outside world. It never mattered to Freddie, though. It never bothered him. It was like, they either get it or they don’t.”

In fact, what nobody had anticipated when News Of The World was released in the punk-dominated autumn of 1977 was exactly how much we were about to ‘get it’ from Queen – to the tune of seven million sales worldwide, making it the most successful Queen album to date.

“After that we stopped worrying about punk or what the critics had to say,” Roger Taylor told me. “We stopped worrying about anything…”

Although Queen were loath to admit it, the thinking behind News Of The World had in fact been more than a little influenced by the lacklustre reception A Day At The Races had received – and not just from the critics. Designed very much as what their former producer Ray Thomas Baker decried as a record that “absolutely screamed ‘sequel’”, it had sold less than a third of what A Night At The Opera had sold in both Britain and America, and less than half what it had sold worldwide. Not a flop, but not “the way things should be going”, as Taylor delicately put it. May reluctantly conceded that it “may have been over-produced”.

Any thoughts of simply aiming for a third bite of the same formulaic cheery were finally dashed when Groucho Marx refused them permission to call the album Duck Soup, which would have been the third time in a row they had ‘borrowed’ the title of a Marx Brothers film. In fact Marx responded by saying they could have the title of his next movie, though: The Rolling Stones Greatest Hits.

Whatever they did next, it became abundantly clear to everyone in Queen that the follow-up to A Day At The Races would have to be something a little different. They had taken more than three weeks to record Bohemian Rhapsody. Now, though, the buzz word around the new album was ‘spontaneity’. To try to enforce this new sense of purpose, a mere two months were booked at Notting Hill’s hip Basing Street Studios and Wessex Sound Studios, a former Victorian church in North London, with all writing and recording completed between July and September. With an American tour booked for November they would have to work faster than at any time before.

To help kick-start the sessions, Roger Taylor brought in demos of two tracks he’d recorded on his own earlier that summer. The first, Sheer Heart Attack, originally aborted from the sessions for the album of the same name in 1974, here with the drummer on lead vocals (replaced on the final album version by Mercury), and redirected as Taylor’s ‘answer’ to punk. Punchy, repetitive, two-chord fury: ‘Well you’re just seventeen and all you wanna do is disappear/You know what I mean there’s a lot of space between your ears…’ That told them snot-gobblers.

The second, Fight From The Inside, was essentially more of the same, although set against a less impatient, rock-steady beat, with Taylor kept on lead vocals, and again having a not-so-sly dig at the punks who saw the 28-year-old idol as now somehow past it. ‘You’re just another picture on a teenage wall, you’re just another sucker ready for a fall…’

It was the band’s principle songwriters, Mercury and May, who came up with the most potent ripostes to any claim that Queen had lost their mojo, with two of the finest, most memorable and long-lasting tracks (after Bohemian Rhapsody) of their career: May’s We Will Rock You and Mercury’s We Are The Champions, both of which open the album, in that order.

A delicious coincidence, perhaps, but the fact that both tracks used the pronoun ‘We’ said a great deal about how the band saw themselves in terms of their own loyal fan base, and the slings and arrows they had suffered on their behalf. We Will Rock You, with its captivating ‘boom-boom-tush’ rhythm and whiplash vocals, topped off by that marvellously bugling guitar solo, was the first real rock anthem to gain traction since the heyday of what we now think of as classic rock. Populist, all-inclusive, this was the ‘come on in, the water’s fine’ rock anthem at its most affecting. A song for the people to sing along to; to clap their hands and stamp their feet to. To march to!

The ‘We’ in We Are The Champions was again meant as a you and me, in it together, banner call, but with more subtle, reflective intentions. Whatever the putative subject matter, Freddie’s best songs were always, ultimately, about his favourite subject: himself. So, too, Champions, yet with its lines about having ‘paid my dues’ and ‘done my sentence, but committed no crime’ Freddie both invites us in to share his lonely bubble, and speaks up for us with his defiant declaration that ‘we’ are the champions, ‘my friends’, before paying the ultimate compliment when he sings, in his quavering sotto voice: ‘You brought me fame and fortune, and everything that goes with it/I thank you all.’ Cue monumental guitar fresco. Towering emotions. Heart pounding, arms-aloft salutes, rivers of man-love… Seated at the piano, head thrown back like Judy Garland, Freddie would be both martyr to the cause and friend-indeed.

“I can understand some people saying We Are The Champions was bombastic,” allowed May some years later. “But it wasn’t saying Queen are the champions, it was saying all of us are. It made the concert like a football match, but with everyone on the same side.”

Or as Freddie put it laughingly in an interview with the Daily Mail in the aftermath of the album’s gigantic success: “To some people I’m still a bitch. I enjoy being a bitch. I enjoy being surrounded by bitches. I certainly don’t go looking for the most perfect people. I’d find that boring. I’m like a mad dog about town. I like to enjoy life.”

In a shrewd move as ever, We Are The Champions and We Will Rock You were paired as a double-A-side first single from the album. It became Queen’s second-biggest-selling hit of all time, spending six months solid on the US chart and eventually sold more than five million copies there.

Such success could not have been taken for granted, though, while they hurriedly tried to finish the album by their self-imposed impossible deadline. Initially working out of Basing Street, where Bob Marley And The Wailers had just completed the Exodus album, the band scurried for ideas. In the end, Mercury contributed only three songs, Champions, My Melancholy Blues and Get Down Make Love, an overheated sex song that hints heavily at the singer’s personal evolution from beautiful girls to handsome boys: ‘You say you’re hungry, I give you meat, I suck your mind, you blow my head…’ What these days might be called a little too much information. But thanks anyway, Freddie, for clearing that up.

“The subject of Freddie’s sexuality never came up because it wasn’t even mentioned within [the band],” Brian May later insisted to me. “Basically, because none of us had any idea that he might be different from us. Is that saying it the right way? I mean, we shared lots of flats and stuff, and I’ve seen Freddie disappear into rooms with lots of girls and screams would emerge, so, you know, we assumed that everything was fairly much the same way as we knew it.

“I’ll go to bed with anything,” said Freddie. “My sex drive is enormous. I live life to the full.” In an interview in 1976 he joked: “I sleep with men, women, cats, you name it.”

"It was only very much later that we realised there was anything else going on with Freddie. I mean much, much later. We were on tour in the States – I don’t even know what date that would have been, but on some fairly big tour – and suddenly he’s got boys following him into a hotel room instead of girls. We’re thinking, ‘Hhmmm…’” he laughed affectionately. “And that’s about the extent of it. Even then, obviously, it was never a problem. I always had plenty of gay friends, I just didn’t realise that Freddie was one of them until much later.”

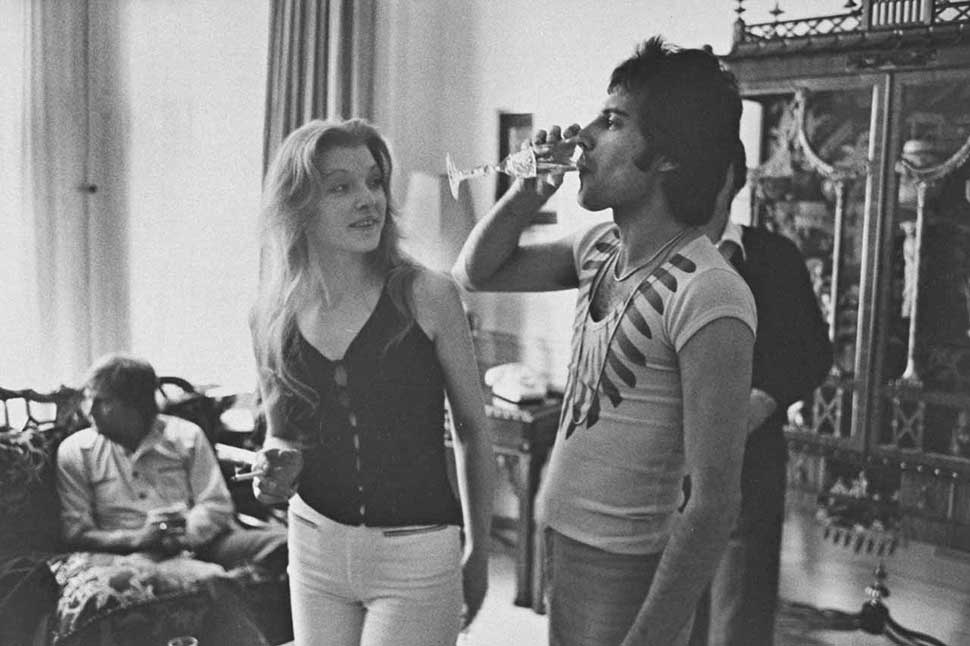

In fact, by 1977 Freddie’s sexuality had become abundantly clear to everyone around Queen. He had almost been publicly outed two years before, when a writer in Ohio was shown into Freddie’s hotel room half an hour early and found him reclining on a pile of cushions, being fussed over by a group of barely-clad muscle-boys. “These are my servants, dear,” Freddie had casually explained.

Although he still enjoyed the close friendship of former girlfriend Mary Austin, he had now bought Mary a luxury penthouse flat of her own in London, while he brought a new special friend, David Minns, into his home. By the time of recording News Of The World, though, Freddie had replaced Minns with a young American called Joe Fanelli.

“After seven and a half years,” he and Mary had “come to an understanding,” Mercury told a reporter in 1978. “I felt that as I’m on tour so much, Mary should have a life of her own.”

Was this his way of saying they now enjoyed an ‘open’ relationship? “I’ll go to bed with anything,” he replied. “My sex drive is enormous. I live life to the full.” Or, as he put it in an interview in 1976: “I sleep with men, women, cats, you name it.”

The other song he wrote for the new album, My Melancholy Blues, was a ritzy-piano jazz-age pastiche with no backing vocals or guitars, just Freddie crooning like an old roué, a pebble beach of champagne corks at his feet, the first light of dawn peeping through the curtains of his four-poster bedroom.

Indeed Freddie was now splitting his time between the recording studio and Sotheby’s, buying an array of expensive antiques and trinkets, filling his Kensington home with Erte prints, Hokusai woodcuts and lacquered Japanese furniture. It was the same on tour, with various crew members recalling numerous occasions when Freddie would arrive breathless at the airport minutes before departure, with a cavalcade of assistants bearing antique furniture, objets d’art, trunks full of clothes and the traditional wooden dolls which he liked to collect, and screech at his tour manager: “Freight it!”

In Japan the promoter would arrange for huge department stores to be opened specially for him at night, so he could go shopping without harassment. “The Japanese call it ‘crazy shopping’,” Freddie boasted. “All these assistants standing there and the place is entirely empty except for me.”

But then he could afford such extravagances. By 1977 when News Of The World was being bolted together, they all could. Such was the combined total of their record sales and concert tour receipts in America that they were all earning individual annual salaries of around £500,000 (approximately £3.3m in today’s money.).

As Freddie was happy to tell one reporter: “Darling, I’m simply dripping with money! It may be vulgar, but it’s wonderful.”

Brian May did the real heavy lifting in terms of songwriting on the album, contributing four tracks, including We Will Rock You, two of which, All Dead, All Dead and Sleeping On The Sidewalk, he also sang lead vocals on – the first time it really hit home just how close May’s voice was to Mercury’s. The former is a lovely, gently paced piano ballad, with a haunting guitar figure coming like weak sunlight halfway through. The overall effect was not hampered in the least by the fact that the lyric was, May explained, “partially inspired” by the death of a beloved pet cat.

Sleeping On The Sidewalk sounds exactly like what it was: an impromptu jam on a day when Mercury wasn’t in the studio, the guitarist indulging his Led Zeppelin blues-jam tendencies, with bassist John Deacon audibly hitting occasional bum notes and May chuckling heartily at the end of the track. Legend has it that the band didn’t even know they were being recorded, but May would eventually cast doubt on that, although he did confirm that the track was recorded live in the studio, with his American-accented vocals added later. It’s the sort of knock-about jam you might hear any rock band lean into during a quiet moment at soundcheck.

May’s other contribution was made of much more substantial stuff. Indeed It’s Late was one of the major highlights of News Of The World. At more than six minutes long, this was his idea, he explained, for a song conceived and performed as a three-act theatrical play – to the point where the verses are called ‘acts’ on the accompanying lyric sheet. But this was no prog extravaganza à la the ‘black’ and ‘white’ sides of Queen II. The guitars on It’s Late are low-slung one moment, high-stepping the next, showing off the same ‘tapping’ technique that Eddie Van Halen would make such a virtue of when his band’s debut Van Halen was released months later. (May revealed that he got the idea for the ‘tapping’ from a Texas guitarist named Rocky Athas, who he’d caught playing at Dallas club Mother Blues the previous year.)

Mercury sings this one, bringing the full force of his catlike vocals to the task.

“It’s another one of those story-of-your life songs,” May would later explain. “I think it’s about all sorts of experiences that I had, and experiences that I thought other people had, but I guess it was very personal. It’s written in three parts. It’s like the first part of the story is at home, the guy is with his woman. The second part is in a room somewhere, the guy is with some other woman, that he loves, and can’t help loving. The last part is he’s back with his woman.”

John Deacon contributed two of the album’s best tracks in Spread Your Wings and Who Needs You. The latter is an utterly charming Spanish stroll, with Mercury’s vocals panned entirely to one audio channel, and May and Deacon’s Spanish guitars over on the other. Ah, the endless joys of stereo. Hard to fathom such simple pleasures now, but throw in May’s maracas and Mercury’s cowbell and you have the kind of track only Queen could have come up with in 1977.

Better still was Spread Your Wings. Destined to become the first Queen single without backing vocals, it was the follow-up single to We Will Rock You/We Are The Champions, and it understandably suffered by comparison. It bothered the world’s charts not at all, yet it’s one of the most masterful and affecting power ballads on the album.

“I suppose it seems like there’s a rule that Freddie and I divide up most of the album, but it’s not,” May told British writer Mick Houghton. “John is a very slow writer, Roger has more material than the group has done, but it’s just a question of choosing material to give each album the right balance. There are no hard and fast rules.

“In terms of contribution, the creative balance has shifted to become much more of a group thing… This is a very crucial time for the group. It’s the point where it would be easy for us to go off and do separate things. But our strength, and that of any group, is that you realise how to use each other in that complementary fashion. That’s the most important thing we have. It works not only on the music side, where we work on all the arrangements, but in the writing, and in the very important psychological side where you’re holding each other together on tour.

“We’ve come to know each other’s strengths and weakness and can play off one another. It’s a very delicate balance, and I’m very aware that it could very easily be upset by something even from outside which threatens the band internally. That’s why it worries me if the media concentrate on me or Freddie. John and Roger are crucial to everything we do, they’re not only a rhythm section. Nothing is farther from the truth. It’s like John is the quiet one. All the press things about John say that, and it’s true in many areas, but in others he’s very much the leader.”

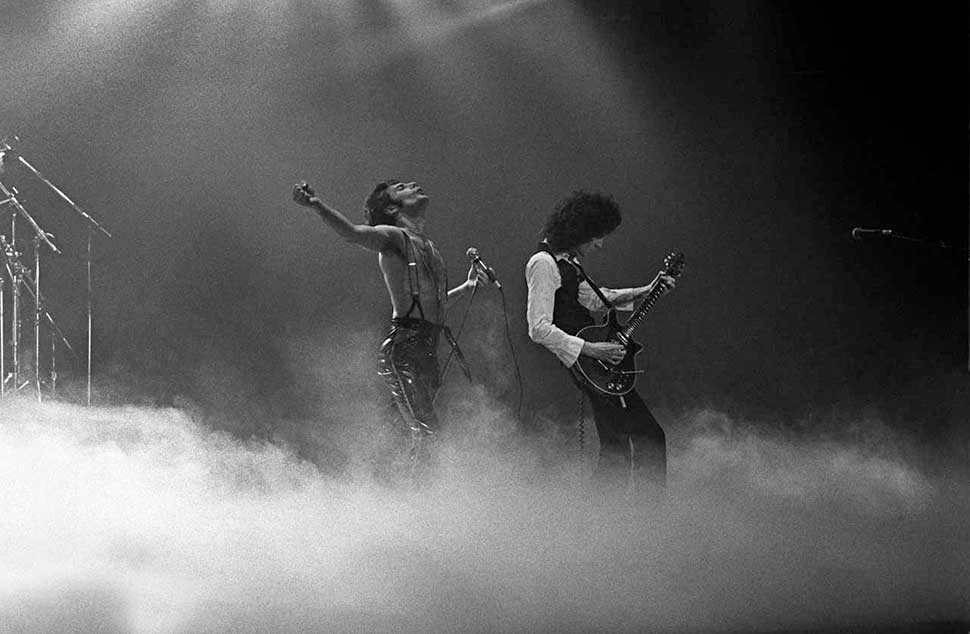

The News Of The World tour opened in Portland, Maine, on November 11, 1977. With all 8,600 tickets sold out at the Cumberland County Civic Center, Queen unveiled their most spectacular stage show yet. Now touring with more than 60 tons of equipment, including a specially modified Crown lighting rig that had first been unveiled at the Earls Court gigs the previous June, this was to be lights, smoke, mirrors and the unsurpassable vision of Freddie Mercury in his absolute prime.

The cost of building the production alone was more than £55,000 (roughly £350,000 in today’s money), a fortune at a time when most rock shows cost a fraction of that. Day-to-day running costs came to nearly £5,000 (approx £30,000 today). It meant the tour would make a profit only in the huge American arenas Queen were now headlining, and actually lose money when they brought the whole shebang to Britain and Europe in 1978.

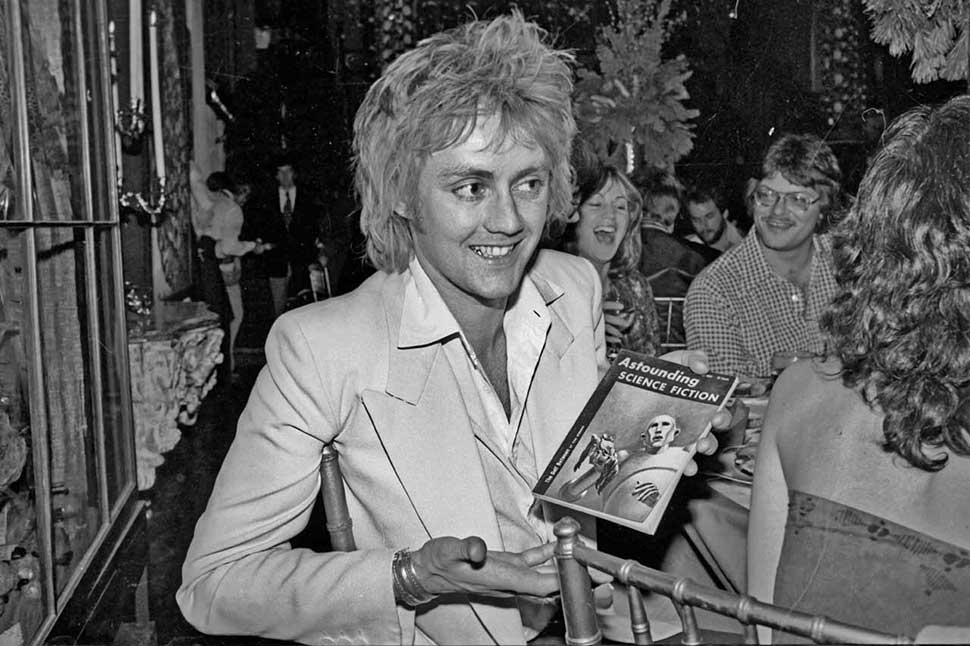

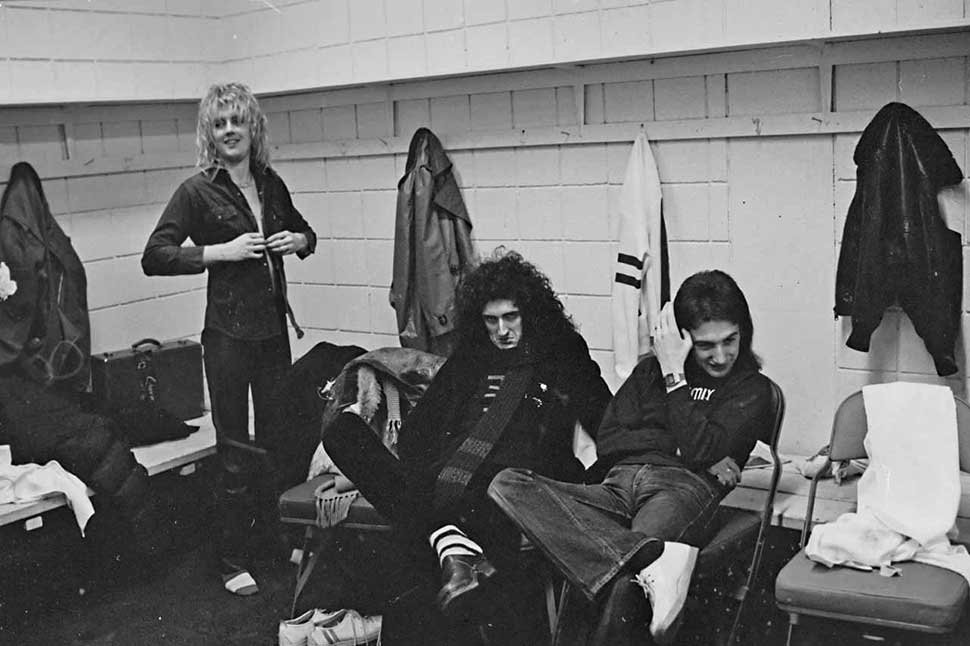

Apart from the spectacular production, the most obvious difference between Queen on tour now was their hair: with the exception of Brian May, who continued to wear his hair long, all the band members now sported short, on-trend hair. Another response to punk fashion, when John Deacon had been the first to trim his locks at the start of the year the others had laughed. Now, though, the even more fashion-conscious Taylor and Mercury followed suit. Not Sid Vicious spiky, my dear, don’t be silly, more like a mid-70s ‘getting good at the back’ David Essex.

Sartorially they were also in ‘transition’, with only May still clinging steadfastly to his bell-bottom trousers, shoulder-peaked blouson and clogs, while Deacon now favoured skinny ties and Taylor vacillated between the two extremes, depending on his mood.

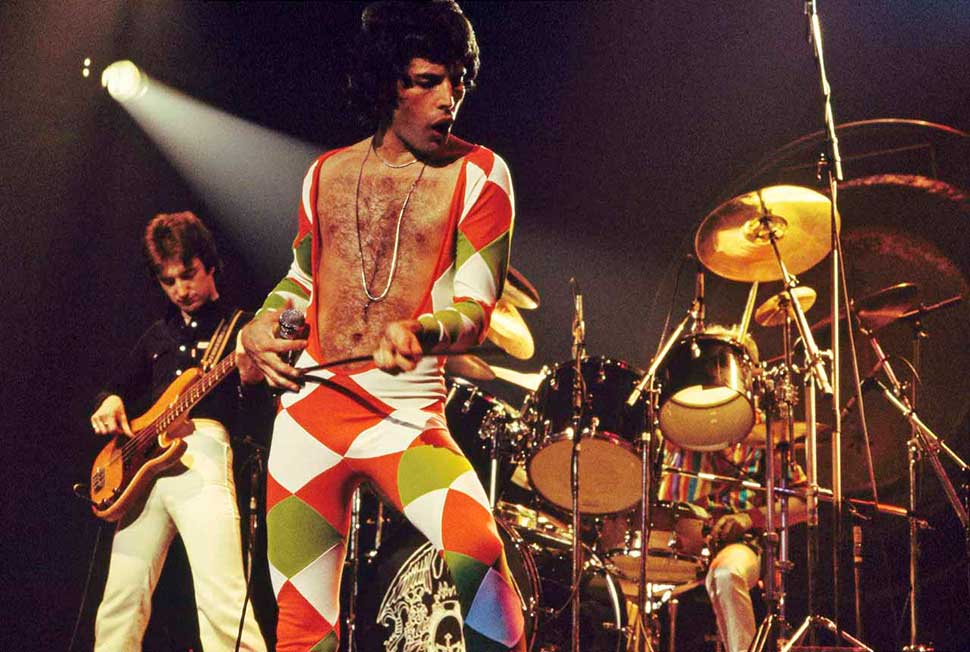

Even Freddie had shortened his noir-mane, although only as far as his shoulders, which along with the fulsome bushy sideburns gave him what local London barbers in those days referred to as ‘an Elvis’. Of course, he hadn’t stopped there, taking everything one step further by going on stage each night in a succession of different-coloured harlequin cat suits (or Nijinsky ballet costumes, as he had scolded the NME) open from throat to navel to reveal his impressively hirsute chest.

“I’m into this ballet thing,” he said. “That’s why I’m trying to put across this Nijinsky costume; and trying to put across our music in a more artistic manner than before. A lot of people just dismiss it and say I’m wearing a silly little outfit, rather than being critical and saying that formal ballet may not be quite right for rock’n’roll.”

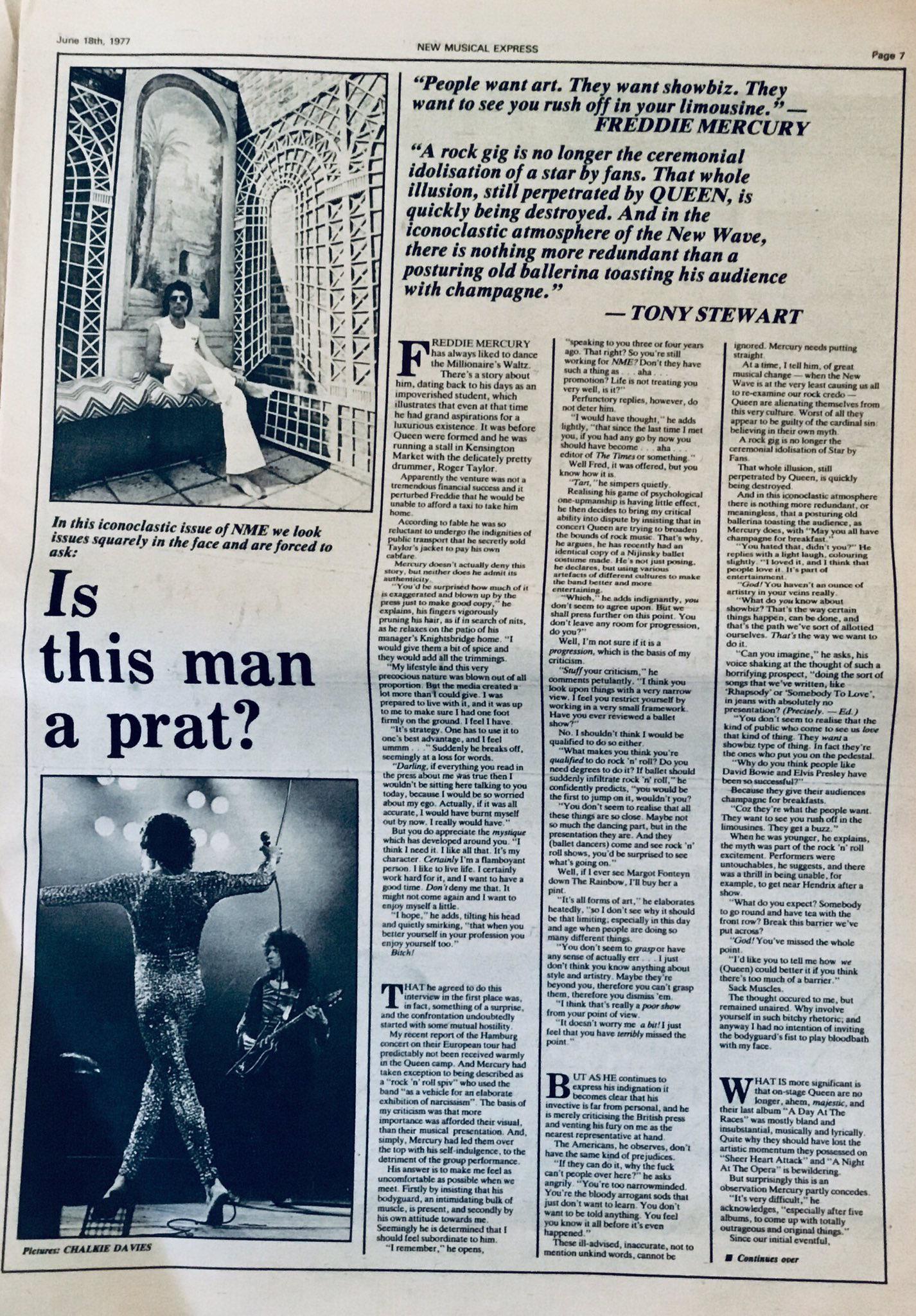

When the NME ran the interview they did so under the headline: Is This Man A Prat? (Read the full interview here.) It was a theme that Sid Vicious took up with Freddie personally one evening during the making of News Of The World.

In a rather wonderful you-couldn’t-make-it-up twist of fate, both Queen and the Sex Pistols had been recording their respective albums at Wessex Studios that summer, the latter in the less plush Studio B.

Sid, rather the worse for wear, wandered into the Queen session where Freddie sat at the piano. “Ullo Fred!" he said. "Have you succeeded in bringing ballet to the masses yet?” Freddie looked up: “Ah, Mister Ferocious! We're trying, dear.”

And then he had him thrown out.

“Ullo Fred!" said Sid Vicious. "Succeeded in bringing ballet to the masses yet?” “Ah, Mister Ferocious!" said Freddie. "We're trying, dear.”

What Sid didn’t know (he hadn’t yet replaced Glen Matlock in the group) was that in another strange conflation of destinies, it was Queen who had been indirectly responsible for one of the career-defining moments of the Pistols’ career when they turned down a spot on Thames TV’s evening magazine show Today at the last minute. So EMI sent their latest signings, the Sex Pistols, to fill the slot with the show’s notoriously louche presenter, Bill Grundy. A real sliding-doors moment in rock history if ever there was one.

Queen had first unveiled their new look when they performed a one-off mini-concert at London’s New Theatre on October 6, in order to shoot the video for We Are The Champions, when members of the Queen fan club who’d agreed to come to the show were rewarded with advance copies of the Rock/Champions single. On stage in America, though, May was still performing his 15-minute guitar solo and Freddie was still camping it up, even if he did now throw the occasional leather jacket over his ballet costume.

Of course, a lot of the real fun on a Queen tour was now taking place off stage after the show. Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones might have set the benchmark for on-tour excess-all-areas in the 70s, but Queen seemed determined to uphold the tradition, punk be damned, by raising the bar several notches higher.

“As soon as we made it,” Mercury said at the time, “we knew there were no longer any limits on what we could do.” Or as May told Classic Rock in 2011: “It was deliberately excessive. Partly for our own enjoyment, partly for friends to enjoy, partly because it’s exciting for record company people, and partly for the hell of it.”

Queen’s 24-date November/December 1977 US tour was such a triumph that even Mercury wondered – albeit only briefly – how they would ever top it. It was full of landmarks such as the two sold-out nights at New York’s Madison Square Garden on December 1 and 2, and another two equally speedily sold-out shows at the Los Angeles Forum on December 21 and 22, and they were now making money hand-over-fist every time they stepped on stage. For their two sold-out shows at the 11,000-capacity Cobo Hall in Detroit, they picked off ticket receipts of $184,477 (approx. $750,000 now). For a show at the Boston Garden they were paid $122,959 (nearly $500,000 now).

The money was now pouring in so fast that in order not to hand over a lot of it to the tax man they were advised to become tax exiles from Britain. But again Mercury just flashed those famous teeth and laughed. “I’ve just been going on wild spending sprees,” he declared. “I’ve been told to cool down because the taxman will be coming to take a large sum away. I’ve spent in the region of a hundred thousand pounds over the last three years.”

Originally there had been tentative plans to take the News Of The World tour to Japan at the beginning of 1978. Queen had been big in Japan, with A Night At The Opera having bestowed Beatles-like status on them. Brian May recalled touching down in Tokyo for the first time, in 1975, and being greeted by more than 5,000 fans.

“We had to be lifted over the heads of the fans,” he said, just to get to their waiting limos. An even bigger Japanese tour had taken place in 1976 after A Day At The Races went to No.1. Now, with NOTW sitting pretty at No.3, the decision to return seemed obvious. Yet they didn’t go for it.

Whatever the reason for not going to Japan, the first few months of 1978 were kept gig-free. Then, in April, came a six-week tour of Europe, before returning, at last, to Britain for five shows in May: the first two at the Bingley Hall in Stafford, followed by three nights at London’s Empire Pool (now known as Wembley Arena).

With Mercury now shunning most music-paper interviews in favour of newspapers and highbrow magazines, this was to be the start of the era of Queen as aloof, unstoppable celebrity entities, far beyond the reach of greasy newsprint weeklies with their sanctimonious attitudes and grim new devotion to anti-rock.

It was the era in which the band journeyed so far down the rabbit hole of an unbridgeable fame that it would eventually reach its toxic nadir in 1984 with their now infamous shows at Sun City in Cape Town, South Africa. Only Bob Geldof’s bold decision to include them as a major part of the massive Live Aid show at Wembley Stadium the following year offered Queen redemption.

But by then their American fame had withered on the vine – again shot down by Mercury’s hubris, pushing the band into a more disco direction with the Hot Space album and flaunting his now outré homosexuality: the tash that just kept giving, the growing bald spot, the tongue-in-cheek that more and more came to resemble simple contempt for his audience – to the point where mainstream American rock audiences now looked to more obvious, more safe role models like Van Halen and Journey for their ass-kicks.

“It’s true that to us there were no boundaries,” May would later tell me. “Alongside trying to never tread the same ground twice, there was always this great challenge of how far can we push things in any direction. You want to be able to explore what’s coming to you in the way of inspiration. It was a difficult compromise to find, but always worth finding once you did find it.”

The News Of The World album, though, would, in time, offer up its own unique Queen legacy. When, in 2001, Queen premiered their new stage musical, giving it the title We Will Rock You was an inspired choice. It seemed to say: we are here not to offer up a rhapsody, or a parody, of any kind. We are to simply entertain you. To rock you. Because we are – and always will be – the champions at this sort of thing. All sense of self-mockery expunged. Even if, as May insists, it still came with a very definite wink of Freddie’s mercurial eye.

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 239, in July 2017.