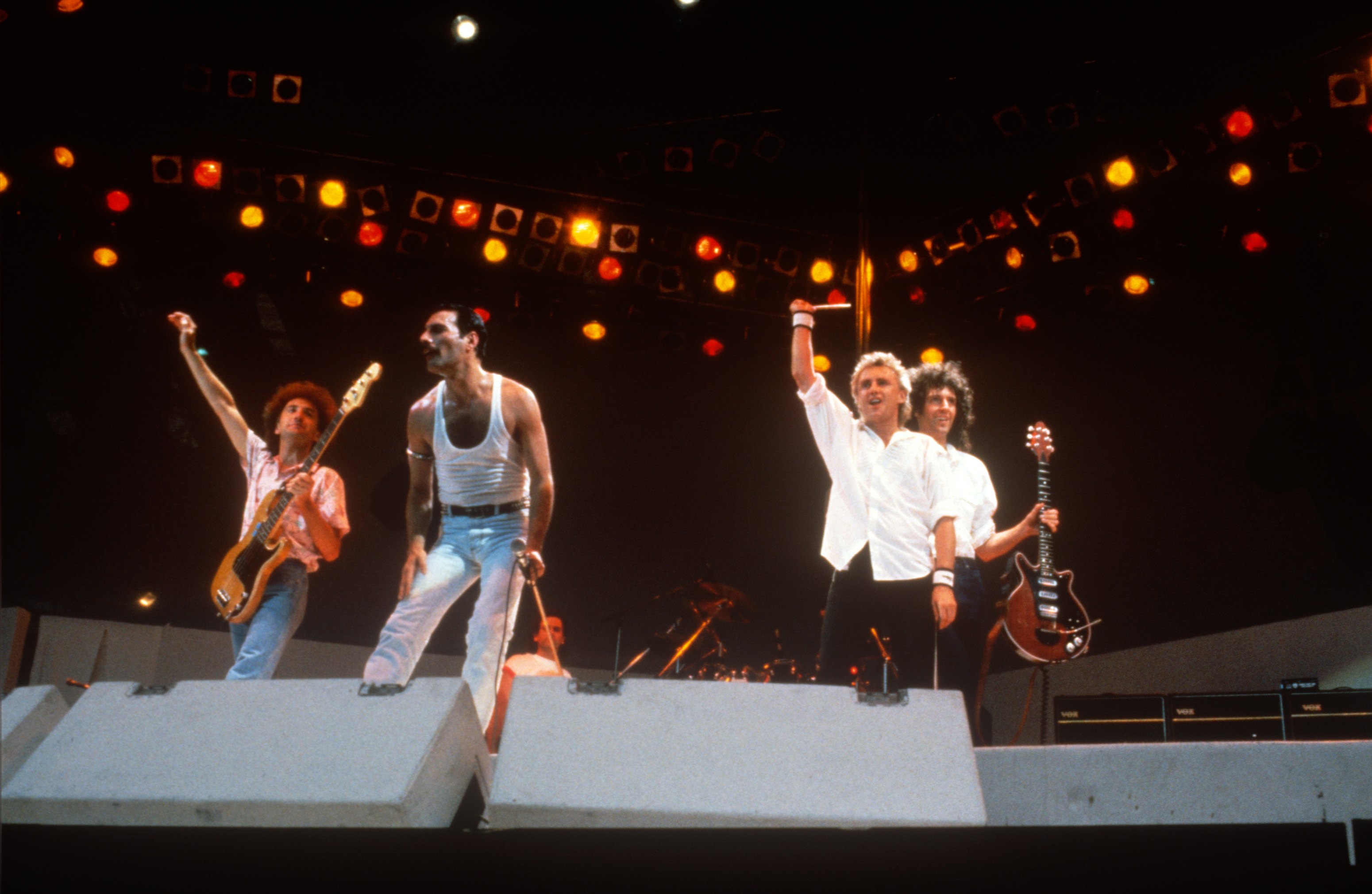

Wembley Stadium, July 13, 1985. When Freddie Mercury skipped like a show pony on to Queen's Live Aid stage, right arm aiming air-hooks at the sea of faces before him, it’s worth remembering that Queen were at a new low point in their career.

Following their controversial decision nine months previously to perform at Sun City, jewel in the segregated crown of apartheid-ruled South Africa – an act in direct violation of United Nations sanctions that would see them fined by the UK Musicians’ Union and placed on a United Nations blacklist – Queen had become pariahs of pop; outcasts of rock; social, musical and political undesirables. It didn’t help that Queen had always been portrayed in the press as pompous, aloof, arrogant even. It was there in their music: arch, grandiose, majestic.

It was there even in the way they performed: Freddie, pouring champagne over the heads of the audience at Madison Square Garden, boasting of bringing ballet to the masses and declaring: “Darling, I’m simply dripping with money! It may be vulgar, but it’s wonderful.”

None of that, though, had ever stopped Queen fans from simply loving them, the same way they did the real Royals: unequivocally, unashamedly, undeniably, no matter what. The stink of those South African shows had clung to Queen though in a way it seemed impossible to shake off. Right up to the moment that Freddie plonked himself down at the piano on stage at Wembley Stadium that hot, never-to-be-forgotten day and picked out the blissfully familiar intro to Bohemian Rhapsody – and all 72,000 people there, plus the 1.9 billion across the globe watching on TV at home, went crazy.

From there it just got better. As they segued into the intro to Radio Ga Ga, Freddie was up and prancing, rolling those shoulders and pursing those lips, eyes sparkling as he waved around that phallic truncated mic stand like a sceptre. Watching a YouTube clip of it now, that glorious moment when the ecstatic Wembley crowd do the synchronised hand-clapping à la the Radio Ga Ga video, the shivers still spiral up the spine.

It’s a moment of musical divinity. An actual shot of rock immortality. And Freddie knew it. As Live Aid organiser Bob Geldof put it: “Queen was absolutely the best band of the day. They played the best, had the best sound, used their time to the full. It was the perfect stage for Freddie – the whole world. And he could ponce about on stage doing We Are The Champions. How more perfect could it get?” The answer: it couldn’t.

No time for losers. That had always been the Queen credo. Yet only in so much as it applied to the band members’ own aspirations. As Brian May later explained to me: “It wasn’t meant as a put-down or an arrogant thing. When Freddie wrote that it was more directed at himself, a kind of self-affirming thing. You’d say: ‘You can’t do that! We’ll get slaughtered.’ He’d just go: ‘Yes we can.’ And he was right.”

Any other band might have given up, such were the unpromising circumstances that greeted Queen’s arrival on to the London scene in 1973. So there was Brian, the nerdy space brain who’d built his own guitar from a fireplace (a what?) and liked to wear capes and clogs on stage; John Deacon, another Bunsen-burning bright boy, who always looked the most doubtful; or as he later put it: “I knew there was something,” but wasn’t “convinced of it” until long after Queen became stars; Roger Taylor, the blond, pretty-as-a-daffodil ex-public schoolboy from Cornwall who’d studied to become a dentist; and up front the brilliant Farrokh Bulsara – Freddie to his great many friends – who’d come from a boys’ boarding school near Mumbai, India and was an arty, fashion-freaked, Hendrix-obsessed, pan-sexual dynamo who’d renamed himself Mercury after a line in one of his own songs. (‘Mother Mercury, look what they’ve done to me,’ from The Fairy King.)

A motley collection of over-entitled popinjays, you might say – and the critics said a lot worse – that had arrived late for the glam party, yet still opted for make-up and satin pants while remaining in thrall to the already past-it hippie fogey-isms of Zeppelin (Ogre Battle, anyone?)

Or as that redoubtable organ of socio-musicological critique Record Mirror put it at the time: “If this is our brightest hope for the future then we are committing rock’n’roll suicide.” Nevertheless, in the summer of 1973 when Queen’s self-titled first album was released, it was hard to place quite where the newbies-come-very-lately fitted exactly.

Bowie had just retired Ziggy; Zep were already five albums and a million rainbows in; Yes and Genesis had already demarcated public-school prog; Rod Stewart and Elton John had cornered the good-geezer/wise-barfly market. What use, then, for another bunch of nail-polished, guitar screeching look-at-mes?

Against that backdrop, what Queen had to offer appeared highly contrived – and in 1973 ‘contrived’ was the worst insult you could throw at a band with pretensions to being true album-oriented contenders. Even small victories came tainted.

When The Old Grey Whistle Test producer Mike Appleton commissioned an animated sequence to run on the show as a visual to accompany a sub-Zep rocker titled Keep Yourself Alive, he admitted he had no idea it was a Queen track. He’d simply “found this white label in my office, no name on it, and liked the opening track”.

There’s one thing nobody could deny, though: Queen were always a great band live. They’d been honing their live act all through the two years it took to complete their first album.

Then in October 1973 they got their big break, opening for Mott The Hoople on a 31-date tour of the UK. You couldn’t be ‘contrived’ and pull off performances of cinematic epics like Father To Son and White Queen. Clearly this was a band that knew how to rock. The worry was whether they would be able to roll with the changes long enough to really catch on.

They certainly talked a good game. May laughed when I reminded him once of Freddie’s famous quote from those pre-fame days about refusing to take public transport. “It’s… slightly embellished,” he chuckled. “I did a lot of bus journeys with Freddie, actually. If you ever get on a number nine bus and go upstairs and go to the front left, that’s where Freddie and I used to sit, going up to Trident [studios, which their then managers, brothers Norman and Barry Sheffield owned] to beat them on the heads, to try and make them do something, cos we felt like we were in a backwater for so many years.”

The backwater years ended in 1974, with the release in March of Queen II; more specifically, the hit single Seven Seas Of Rhye. More specifically still, their spectacular performance of it on Top Of The Pops. That weekly TV chart show meant everything in that largely pre-video age. As an over-impressionable 15-year old Ziggy-kid with Mott-spots and Zep cravings, for me Top Of The Pops was where Queen really kept themselves alive in the mid-70s.

One wild-eyed shot of them doing Seven Seas Of Rhye had me stealing a ten-bob note from my mum’s purse in order to purchase the single during school lunch hour the next day. It was the same when they came on doing Killer Queen – the most sublimely brilliant single of 1974 – later the same year. As for the adrenalin overload of watching them do Now I’m Here just weeks later. None of that ‘ironic’, ‘we know that you know we’re only miming’ 80s nonsense with Queen in 1974.

Look at the clip now of Freddie waggling his black nail-polished fingers in your face during Killer Queen, wrapped in bum-warmer fur while Brian and John throw cooler-than-thou, rock-idol shapes and Roger pouts as he pounds, and tell me you think they’re faking it.

Looked back at now, it’s easy to see the rest of Queen’s career trajectory as an enviably upward line of unbroken success. That after the attention-grabbing Queen II and the pay-off of Sheer Heart Attack, those two albums released within eight months of each other, their formula for success was firmly established.

May brought the hard rock (Now I’m Here), Mercury the sophisticated pop (Killer Queen), while Taylor and Deacon were the Ringo and George of the group – the side salad to the steak (although both would later contribute their own significant hit singalongs to the Queen canon.)

In fact, the mid-70s found the band in a perilous place. They were big at home in Britain, and through Killer Queen getting bigger in Europe, and had the first signs of a US breakthrough when both Killer Queen and Sheer Heart Attack reached No.12 on their respective charts, but still just wage slaves, living in rented accommodation, sashaying around the clubs at night, scrabbling around to pay the bills the next morning.

Roger Taylor later recalled the band coming home from headlining two shows at the 15,000-capacity Budokan in Tokyo in the spring of 1975 and going home to his tiny bedsit in Richmond, and “we were still on sixty quid a week”.

John Deacon, by now married, had to beg for the £2,000 he needed as a deposit on a house, while the Sheffield brothers who managed Queen were supposedly driving around in Rolls-Royces.

Something would have to be done. Quickly.

Enter the most feared management figure in the London-based music business of the 1970s: Don Arden. Arden (father of Sharon, soon-to-be Osbourne) once described for me how he became involved with Queen.

“Queen was at its height at the time, yet they were penniless,” he said. “They didn’t even have a car between them. Freddie and the rest of the guys in the band were friendly with Sharon, and so they asked for [my] advice. I [said] my advice would be to get their coats on and fuck off! But they said they wouldn’t do that because they were terrified of the Sheffield boys – they had the group believing they ruled the streets of Soho. Well, we would see about that.“

Queen was signed to EMI, but the deal the label had done had been via the brothers’ own production company. It was the same with all the deals the band made: nothing was signed directly to them, but to the brothers’ production company. As a result, the brothers not only owned their management contract, they owned their recording contract and their song publishing too.

As a result, said Don, “the Queen boys had a roof over their heads and an old van they travelled in when they were on tour. I couldn’t believe it. It was like they’d never sold a record.

I said: ‘Well, what do you want me to do?’ They said: ‘We want you to manage us, Don.’ I said: ‘Okay, get your lawyer to send me a letter confirming your intention to come to me, and I’ll go and sort these fucking guys out for you.’ We shook hands on it, and the very next day I drove up to Soho to see the Sheffields

"I didn’t actually bother making an appointment, I just turned up. I knew they were fakes. Sure enough, when I walked into their office and announced myself it scared the hell out of them. They began talking very fast, chattering away about how they’d just been shopping with their wives buying them jewellery.

"They were starting to make me sick, so I looked at my watch and said: ‘Well, we’ve done with the niceties. Now listen to me very carefully. I’m not here to talk about your fucking wives. I’m here to inform you that you no longer represent Queen. It’s over, okay? Finito.’ “They looked at each other. They might have put the frighteners on Queen, but did they have the balls to actually take on Don Arden? No, they fucking didn’t.

"They couldn’t even look me in the eyes. They were worried about what was coming next. Would I have a go? Maybe. But I wasn’t evil to them. I didn’t have to be. I just told them how stupid I thought they were. In fact I gave them a bit of a lecture. ‘If you’d at least bought them all a fucking car and put a few quid in their pockets it would probably never have come to this,’ I said. ‘Why didn’t you do all that and then think about screwing ’em? Well, you’ve blown it now. They’re gone.’ “They hung their heads in shame.

"I told them that if they agreed to walk away right now this instant, they would get a cheque for a hundred thousand pounds for their trouble and they would never have to see me again. I pointed out that if they didn’t agree, however, the group would still be gone but they wouldn’t get any money at all, and they’d have me to deal with. They sensibly took the money.

“When I got back to the office that day and told [Queen] what I’d done they literally wept for joy. They were hugging me and kissing me. Then as soon as they got their hands on the money I never heard from them again.” In fact, as Sharon Osbourne later explained to me, the band had decided instead to go with Elton John’s manager, John Reid.

The reason? “Freddie,” she said. “John was gay too and I think Freddie just felt safer with him.” A shrewd music biz guru, Reid immediately proved his worth by making a decision that would transform the band’s lives. It was Reid who put his foot down and absolutely insisted that the next Queen single should be a track that, on paper, appeared the least commercial of all the new material they were working on. A mock-opera, if you will, part ballad, part waltz, part rocktastic headbanger.

It was called Bohemian Rhapsody. And when the suits at EMI heard it they nearly fainted. This was a joke, right? Wrong. This was a stroke of genius. We all know what happened next.

Roy Thomas Baker, the pop perfectionist who had produced all the Queen albums up until then, later recalled his time working with Freddie, listening, mouth open, as the singer demonstrated on the piano an “idea for a song” that he had. “It was going to be a brief interlude of a few Galileos and then we’d get back to the rock part of the song,” Baker memorably recalled years later.

“When we started doing the opera section properly, it just got longer and longer.” Days went by with the recording. Every time a perplexed Baker thought they were done, “Freddie would come in with another lot of lyrics and say: ‘I’ve added a few more Galileos here, dear,’ and it just got bigger and bigger.” There had famously been long, ‘journey’ songs on albums before; tracks identified by their construction from seemingly disparate elements that built to a towering crescendo. The Beatles with A Day In The Life from the Sgt Pepper’s album springs to mind easily, as does Led Zep’s Stairway To Heaven. Also, most recently in the mind of Freddie Mercury, the three-part pop operetta Une Nuit A Paris from 10cc’s summer 1975 album The Original Soundtrack.

None of those, though, had ever been released as a single. Yet when Capital Radio DJ Kenny Everett played it 14 times in two days, EMI commissioned the now legendary video, based on images from photographer Mick Rock’s iconic session with the band from the previous year. The result was not just the biggest hit of the year, but the biggest hit – certainly the most memorable – in British music history up to that point. One that perfectly encapsulated everything that we now think of when we think of Queen: rock grandeur, pop camp, multi-tracked musical ostentation, workson-many-levels lyrical imagery, fun, frisson, ‘you must be fucking joking’, ‘no I’m fucking not’ genius. All wrapped up in a song that would later be revealed as surprisingly autobiographical.

For someone who appeared supremely confident, the truth is that by 1975 Freddie was in a mental and emotional quandary. Although he’d been in a loving relationship with boutique owner Mary Austin since before Queen, he’d been experimenting with men since he was at boarding school.

Still living with Mary at the time he wrote Bohemian Rhapsody, but now also involved with music publisher David Minns, Freddie had also increasingly begun to enjoy casual gay sex on the road.

As Brian May later explained to me: “The subject of Freddie’s sexuality never came up. Basically, because none of us had any idea that he might be different from us. Is that saying it the right way? I mean, we shared lots of flats and stuff, and I’ve seen Freddie disappear into rooms with lots of girls and screams would emerge, so, you know, we assumed that everything was fairly much the same way as we knew it. It was only later that we realised there was anything else going on with Freddie. We were on tour in the States, and suddenly he’s got boys following him into a hotel room instead of girls. We’re thinking: ‘Hmmm…’ And that’s about the extent of it. Even then, obviously, it was never a problem. I always had plenty of gay friends, I just didn’t realise that Freddie was one of them until much later.”

In that context, it’s easy to read the lyrics to Bohemian Rhapsody as a cry for help almost. Certainly a message in a bottle thrown out to sea by someone feeling isolated, confused, lost. The poor boy, confused between what’s real or just fantasy: ‘Because I’m easy come, easy go, little high, little low/Any way the wind blows, doesn’t really matter to me…’ None of which was easily detectable to the outside world in the mid-70s, as from this point on Queen really did take on the mantle of rock royalty.

The album A Night At The Opera emulated the daring and sophisticated splendour of its most famous track, and became just as big a hit in its own realm, their first UK No.1, their first multiplatinum top-five hit in the US, and gold and platinum stop-offs around the world. From hereon in, everything about Queen would be defined in epic proportions.

Not just the success – all of their albums followed A Night At The Opera into the upper reaches of the world’s charts, as did most of their singles, all the way up to The Game in 1980, which hit No. 1 in both Britain and America, their last to do so – but also the manner of that success, the sheer scale of their endeavours. Not just the increasingly over-the-top songs, but also the videos, live shows, album launch parties and of course the personal lifestyles of the band. The infamous launch party in New Orleans in 1978 for the Jazz album featured a guest list of 500: rock and film stars, street freaks and media loyalists; oysters, lobster, the finest caviar, champagne; dwarves serving cocaine from trays strapped to their heads; contortionists, fire-eaters, drag queens, naked dancers in cages suspended from the ceiling; grand marble toilets ‘serviced’ by prostitutes of both sexes.

“Most hotels offer their guests room service,” Freddie giggled. “This one offers them lip service.” When the 1979 single Crazy Little Thing Called Love went to No.1 in America Freddie that boasted it had taken him just 10 minutes to write, doing an Elvis impersonation while lying in a bubble bath snorting cocaine in his £1,000-a-night suite at the Bayerischer Hof Hotel in Munich. As you do.

Ironically, the bigger and more ostentatious became the Queen modus operandi, the more they were accused of being hollow, preposterous, inalienable. Yet nobody mocked Queen more than Freddie Mercury.

“Of course, dear,” he told one writer. “We’re wonderfully shallow. Our songs are like Bic razors – designed for mass consumption and instantly disposable.”

Teased about the elaborate stage productions they now toured with, Freddie laughed and said: “We’re the most preposterous band that’s ever lived.”

As Brian May told me: “The most popular misconception of people outside the people who ‘get it’, is that [Freddie] took himself seriously. [They] didn’t understand that although he took his work incredibly seriously, there was always that element of self-parody, if you like, in Freddie. He was always slightly tongue-in-cheek; there was always a little twinkle in his eye. I think that’s what was missed by the outside world. It never mattered to Freddie, though, it never bothered him. It was like, they either get it or they don’t.”

Such hubris reaps its own bitter rewards, of course. And just as Queen seemed like they couldn’t get any higher – Another One Bites The Dust (written by John Deacon) from The Game became their second No.1 hit in the US, followed a year later by their only UK No.1 of the 80s, their David Bowie collaboration Under Pressure – they finally flew close to the sun and badly singed their wings.

They didn’t make it public, but by the end of making The Game Queen had all but broken up.

“Yes, we all walked out at various times,” May admitted. “You get hard times, as in any relationship. We definitely did. Usually in the studio; never on tour. On tour you always have a clear, common aim. But in the studio you’re all pulling in different directions and it can be very frustrating. You only get twenty five per cent of your own way at the best of times. So, yes, we did have hard times. Feeling that you’re not being represented, that you’re not being heard. Because that’s one of the things about being a musician, you want to be heard. You want your ideas to be out there. You want to be able to explore what’s coming to you in the way of inspiration. It was a difficult compromise to find, but always worth finding once you did find it.”

Speaking nearly 20 years later, John Deacon put it more simply: “Once we’d achieved that level and been successful in so many countries in the world, it took away some of the incentive.”

The bottom of the barrel arrived with their 1982 album Hot Space. After a decade at the top, Queen had demonstrated more versatility than any group since The Beatles. It seemed they could do anything, not just bring opera to the charts – opera, dude! – but also Aretha-soul (Somebody To Love), effervescent pop (Don’t Stop Me Now), music hall (Good Old Fashioned Lover Boy), rockabilly (Crazy Little Thing Called Love), heartland rock (Fat Bottomed Girls), Chic-style funk pop (Another One Bites The Dust)…

With Hot Space they decided they could do disco. “Freddie and John definitely shared an interest in exploring that funk direction,” said May. “I remember Roger’s first reaction to Another One Bites The Dust, which was unprintable! But he got into it in the end. And I make no apologies for the Hot Space album. I was well into it at the time. It took me a while to get into that philosophy of sparseness but it was very good for us, it was a good discipline and it got us out of a rut and into a new place.”

The trouble was, disco had already been done to death, and only recently. By releasing the single Body Language, a sleek, highly impressive electro-disco bump’n’grind, they had alighted on the form just as rap and soon-to-be hip-hop had reinvented the genre.

But Freddie couldn’t see it. Now living in New York and a nightly habitué of the small-hours gay and S&M clubs where such music writhed and thrived, it wasn’t just the almost suffocating sounds of the tightly wound turntables he sought to emulate, it was the whole limb-tangled scene.

Not only had ‘rock’ band Queen abandoned their musical foundation stones, also their singer had cut his hair butch-short and grown one of the moustaches that characterised the after-dark scene he now called home. Freddie’s change of image from svelte 70s rock star to short-haired and moustachioed pop diva was the moment when Queen’s career in America began to tank.

“I think there’s a grain of truth in that, but there was a lot more going on, a number of factors,” May insists. “One of the factors was the video for I Want To Break Free. We’re talking about a bit later now, but I know that that was received with horror in the greater part of America. Because they just didn’t get the joke, you know. To them it was boys dressing up as girls and it was unthinkable, especially for a rock band. I was actually in some of those TV stations when they got the thing and a lot of them refused to play it. They were visibly embarrassed about having to deal with it. So that was one factor.”

He also cited the band’s switch of US label in the early 80s: “We had spent a million dollars getting out of the Warner-Elektra deal to get on to the Capitol label. And Capitol got themselves into a heap of trouble with [a dispute that raged in the early 80s over the alleged corruption of independent record promoters in the US]. It was basically the ring of bribery that [went] on to get records played [on US radio]. There was a government enquiry into it and everybody shut down very, very fast.

“Without going into it too deeply, Capitol got rid of all their ‘independent’ guys, and the reprisals from the whole network were aimed directly at all the artists who had records out at that time. We had Radio Ga-Ga out, which I think was number thirty and rising, and the week after that it disappeared from the charts completely. We got caught up in all that due to no fault of our own.” Mercury, as ever, affected not to care, as if nothing really mattered. Queen toured South America instead of North America.

“Japan and Europe also became a huge thing for us. Eastern Europe opened up. And we were not seen for quite a long time in the States, due to a combination of all the circumstances that I’ve described. Plus the fact that Freddie didn’t want to go back smaller than we’d been before. He was like: ‘Let’s just wait, and then soon we’ll go out and we’ll do stadiums in America as well.’ Only of course we never did.”

For the Queen traditionalists – and there were still many millions of them – the release of The Works, in 1984, was an unexpected joy. To call it a return to form would be unjust. It was another move forward, just less deliberately weird than its much-derided predecessor. The electronics were there not just to unbalance expectations, but, as in royal days of yore, to become another Queen-endorsed part of the overall musical majesty.

Radio Ga Ga, written by Taylor, was a giant hit, heralding what appeared to be a new chapter in the ever-unfolding story of Queen. Even better, though, was I Want To Break Free, with its gorgeous loping rhythm that John Deacon had again come up with, and blissfully muted synth solo, played by the great Fred Mandel, the first significant extracurricular musician ever to appear on a Queen record.

The video was a hoot, of course, with its cringingly short skirts, crooked women’s wigs, badly drawn lippy and droopy cigarettes. The track was fabulous, joyous and, when listened to alone, away from the hoovering video, a wonderfully fully realised demand for the one thing rock music was originally invented to champion: the freedom to be oneself, whoever the hell that might be, when no one else is looking.

A few years later I attended the funeral of Brian Munns, the brilliant EMI press officer who had attended Queen’s career through thick and thin. I was deeply moved to discover he had requested that I Want To Break Free be played as his coffin was ushered into the flames of the crematorium.

By then Freddie was dead too, but to hear him crooning ‘It’s strange but it’s true/I can’t get over the way you love me like you do’ brought a happy tear to the eye.

For Freddie and Brian, for all of us. I also recalled the harsh criticism that news that Queen had been added to the Live Aid bill had engendered among my colleagues on the so-called free press. And how none of it really mattered by the time Freddie, Brian, John and Roger took Wembley and the world by storm that summer.

When, exactly 20 years later, I asked Brian May what he would list as Freddie Mercury’s greatest attributes as live performer, apart, of course, from that fantastic four-octave voice, he replied: “I suppose that combination of such daring and audacity, but also a great vulnerability as well.”

Isn’t that what made them Queen, though, that ability to be something more than just a rock band?

“Well, that’s very kind of you,” he said. “It’s true that to us there were no boundaries. Alongside trying to never tread the same ground twice, there was always this great challenge of how far can we push things in any direction.”

And on those several occasions when they went too far?

“You’d have to ask Freddie.”