"What most people only think of or whisper in private, Kevin would scream at the top of his lungs. That kind of honesty is rare, and it comes with a price": the chaotic story of Kevin DuBrow and Quiet Riot

Six years after their debut album, Quiet Riot became an overnight success with Metal Health, the first 'heavy metal' album to top the US charts

Quiet Riot were originally formed in Los Angeles in 1973 by guitarist Randy Rhoads, joined swiftly by frontman Kevin DuBrow. By the time of their breakthrough a decade later, Rhoads was gone, his place taken by Carlos Cavazo and the lineup completed by bassist Rudy Sarzo and drummer Frankie Banali. Their third release, Metal Health, famously became the first heavy metal to top the US chart. In 2013, we told their story.

May 29, 1983. 11.30am. At Glen Helen Regional Park in San Bernadino, California, 60 miles from Los Angeles, the second day of the US Festival was beginning under a hot sun in a cloudless blue sky. The vast expanse of this open-air venue was already filled with people – as many as 375,000. And a little known LA metal band was about to claim a famous victory.

The US Festival – pronounced ‘US’ as in ‘us and them’ – was the biggest rock event of the year in America. On the 28th, dubbed ‘New Wave Day’, The Clash topped a line-up that included Stray Cats and Men At Work. ‘Rock Day’, on the 30th, would feature David Bowie, Stevie Nicks and the up-and-coming U2. But ‘Heavy Metal Day’, on the 29th, was the big one – with three times as many people in attendance. Headlined by Van Halen, the line-up also featured Scorpions, Triumph, Judas Priest, Ozzy Osbourne, Mötley Crüe… and, first up on stage, that aforementioned little-known band, Quiet Riot.

Formed in the mid-70s, Quiet Riot had grafted long and hard to get to this point. Their chief claim to fame was that the band had once featured Randy Rhoads, the guitarist who had gone on to stardom with Ozzy Osbourne before being killed in a plane crash in 1982. But now, at last, Quiet Riot were signed to a major label for their third album, Metal Health. They were primed for their breakthrough, and the US Festival would be their testing ground.

For Quiet Riot’s drummer Frankie Banali, this was a day he would never forget. “It was a whirlwind,” he recalls. “Two days before, we played an outdoor show in El Paso, Texas. It was a sweltering 102 degrees in the shade, and a dust bowl. We jumped off the stage and drove to the airport still in our stage clothes and covered in muddy sweat. On arrival in LA, we went to a hotel where a full-on party had taken over the premises. And at 11.30 the next morning, after very little sleep, we hit the stage at the US Festival and never looked back.”

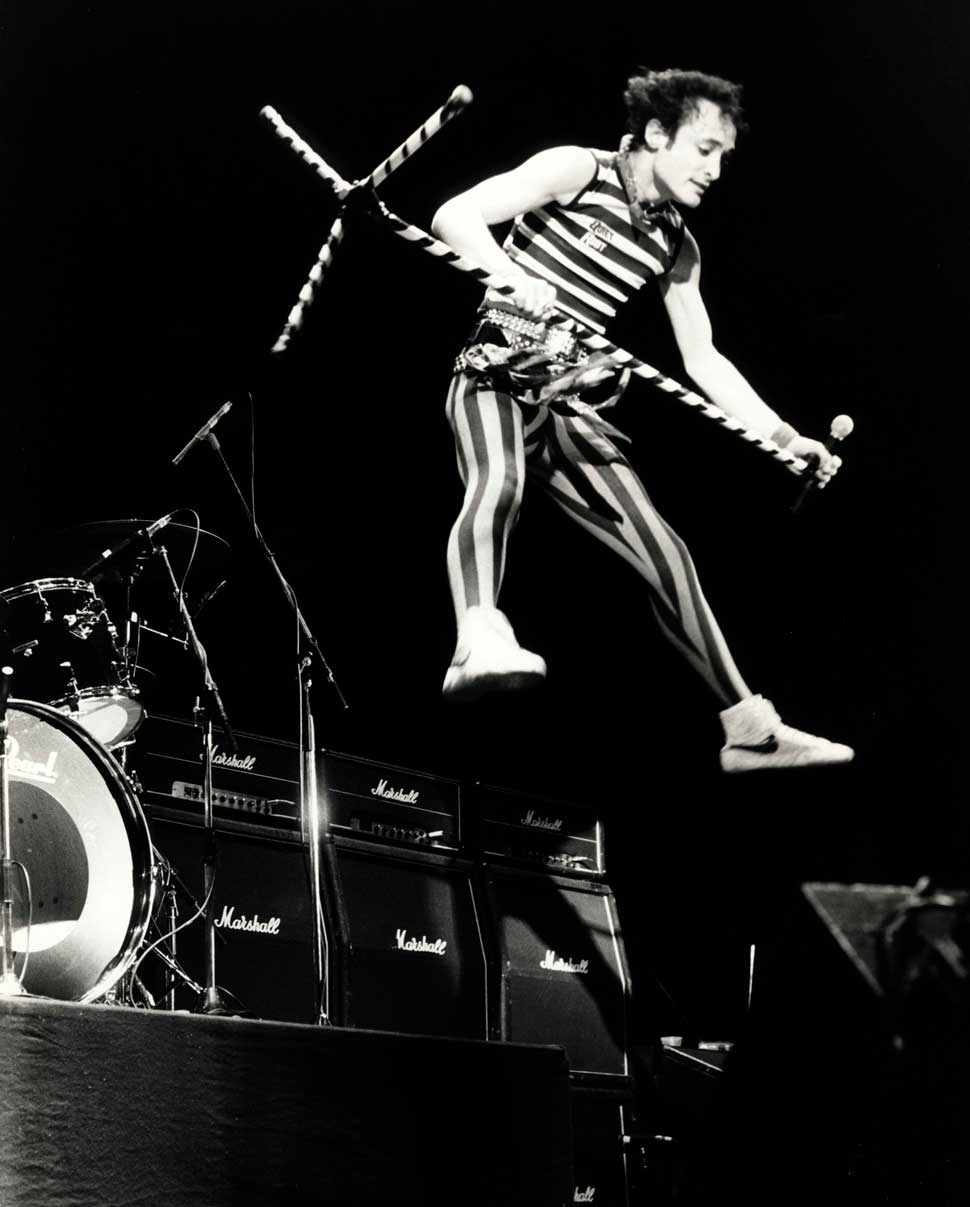

This was their moment and they seized it by the balls. Singer Kevin DuBrow, his loud voice matched by an outfit of red PVC pants and braces and gaudy striped vest, ran the show with bug-eyed intensity, gurning like a lunatic as he urged the assembled “heavy metal maniacs” to clap and sing and punch the air. And when the band’s 40-minute set ended with their new album’s title track – featuring the brilliantly idiotic chorus, ‘Bang your head! Metal health will drive you mad!’ – Frankie Banali couldn’t believe what he was seeing and hearing.

“There was no horizon,” he says, “just miles upon miles of faces singing, ‘Bang your head!’ I was so elated. Quiet Riot was on the same stage as Judas Priest, Ozzy, Scorpions and Van Halen – the cream of the heavy metal crop. For us, it was a ground-breaking moment.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Before the year was out, Quiet Riot would be one of the top-selling acts in America. The Metal Health album would go to No.1 on the US chart. The single Cum On Feel The Noize, a remake of the 1973 hit by British glam rock stars Slade, would reach the top five. And after years of disappointment and disillusionment, Quiet Riot became superstars.

As Banali says now: “We were breaking records, selling ridiculous amounts of albums every week. Quiet Riot was a phenomenon. We were living the dream…”

In 2013, Quiet Riot is Frankie Banali’s band. He is the sole remaining member from the classic line-up that made Metal Health, and he now acts as the band’s manager. But the story of Quiet Riot, as Banali recounts it, is essentially a tribute to the man who is longer around to tell the tale.

Kevin DuBrow, who died from a cocaine overdose in 2007, was the driving force behind Quiet Riot’s success. It was DuBrow who co-founded the band in 1975 and led it through the toughest times; DuBrow whose voice and outsized persona defined the Quiet Riot sound, and whose bloody-minded determination inspired the band’s greatest triumphs.

As Banali says: “Kevin was crazy, loud, with a huge ego. He was the flag-bearer for Quiet Riot. And he really was bigger than life.”

DuBrow certainly made a powerful impression on Banali when they first met in 1977. Banali, at 26, had recently left his hometown of New York to chase his dream of rock’n’roll stardom in LA, where Quiet Riot were already established as one of the most popular bands on the Hollywood rock scene, alongside Van Halen. A rivalry existed between the two bands: DuBrow was as cocky and outspoken as Van Halen’s lead singer David Lee Roth, and Randy Rhoads was an emerging guitar hero comparable to Eddie Van Halen. But in one respect, Quiet Riot were ahead. They were first to get an album released, albeit only in Japan.

Banali says: “Quiet Riot was the band to see because of Randy Rhoads. And I thought Kevin was great – so self-assured, abrasive, nonconformist. He reminded me of everyone I grew up with in New York City. But he didn’t intimidate me at all.”

Banali attended various Quiet Riot shows with a former bandmate from New York, bassist Rudy Sarzo, who had also relocated to LA. In 1978, Sarzo joined Quiet Riot in place of founder member Kelly Garni, shortly after second album QRII was released. On Sarzo’s recommendation, Banali was offered an audition with the band as a potential replacement for drummer Drew Forsyth. At this first time of asking, Banali turned down the chance to join Quiet Riot in favour of Monarch, a power trio led by Michael Monarch, former guitarist for 60s legends Steppenwolf. But the next time that DuBrow offered him a job, in 1980, Banali accepted.

Following a brief tenure in Monarch, Banali had worked as a session drummer for artists including Billy Idol and short-lived supergoup Hughes/Thrall. The session work paid well, but Banali wanted to be part of a band – a kick-ass heavy metal band that would sell millions of records. And it was a vision he shared with DuBrow.

After Randy Rhoads left Quiet Riot to join up with Ozzy in 1979 – a route followed by Rudy Sarzo in 1981 – DuBrow had formed a new band under his own name. And by the start of 1982, a solid line-up was completed by bassist Chuck Wright and guitarist Carlos Cavazo. But on March 19, 1982 came the shocking news that Randy Rhoads had been killed. And in the aftermath of this tragedy, Quiet Riot would be reborn.

Banali recalls: “When I first heard the sad news of Randy’s passing, I got in touch with Rudy right away to make sure he was okay. He stayed on with Ozzy for a while, but he really couldn’t continue without Randy, as they were very close. I sensed that right away. So when we parted company with Chuck Wright, I asked Rudy if he might be interested in coming back to us. And he was.”

Once Sarzo had returned, it was quickly decided that the group should revive the Quiet Riot name, partly in memory of Rhoads. But when they set to work on new music, they made a clean break from the past. The pop-rock style of the first two Quiet Riot albums was very much a product of the late 70s. In its place came a harder and punchier sound perfectly attuned to a new era and a young audience plugged into MTV.

In September 1982, Quiet Riot signed to CBS. The band’s third album would be released through Pasha Records, a subsidiary label operated by their producer Spencer Proffer. The recording budget was small, but as Banali says: “We were just thrilled to finally be making a record.”

And when the album was completed, the feeling within the band was unequivocal. “We all thought it was a great record,” Banali says. “We just didn’t know if anyone would agree with us.”

Quiet Riot didn’t have to wait long for validation. When the Metal Health album was released on March 11, 1983, it was hailed by Kerrang! as “five-star rock”, with writer Howard Johnson correctly predicting: “Quiet Riot is a band destined for big things at last.”

With Metal Health, Quiet Riot were not reinventing the wheel, as Van Halen had done with their debut in 1978, or as Randy Rhoads had done with Ozzy on Blizzard Of Ozz and Diary Of A Madman. Nor was Metal Health a ground-breaking rock album like two other huge hits of 1983, ZZ Top’s Eliminator and Def Leppard’s Pyromania. Metal Health was simply a great all-American heavy metal album. And with its title track, Quiet Riot had created one of the all-time classic balls-out metal anthems.

Its heavy riff was based on a song called No More Booze that Cavazo had played in his previous band, Snow. And its gonzoid lyrics were inspired by what Sarzo had witnessed on tour with Ozzy in the UK. Says Banali: “The ‘Bang your head’ line was pure Kevin, but the idea came from Rudy. He told Kevin about English fans playing air guitar and moving their heads as if banging them on the stage. So Kevin took the ball and ran with it.”

For Banali, this was the band’s “definitive” song. But what gave Quiet Riot their breakthrough hit was a track that the band hadn’t even wanted to record.

“Cum On Feel The Noize was the producer’s idea,” Banali admits. “He wanted a safety commercial track.” DuBrow had in fact suggested that they cover another of Slade’s hits, Mama Weer All Crazee Now, but Spencer Proffer was adamant about Cum On Feel The Noize, and his instincts were proved right. It was the hit that sent Metal Health to the top of the US chart.

On November 15, 1983, a day after Frankie Banali’s 32nd birthday, Quiet Riot were about to go on stage as the opening act for Black Sabbath in Rockford, Illinois – the home of Cheap Trick – when their manager informed them that Metal Health would be hitting No.1 within two weeks. “You get the chart numbers early,” Banali explains. “So we knew right there and then that we had accomplished what we had only dreamed of – a No.1 record.”

They celebrated with a case of Dom Perignon donated by Black Sabbath. “That was very generous of those guys,” Banali says. “And that case lasted about 20 minutes! But we didn’t kick up our heels and rest easy. We wanted to prove that we deserved our success.”

The year ended with Quiet Riot’s first ever UK dates, opening for Judas Priest. And in in interview for a Kerrang! cover story, Kevin DuBrow was in typically ebullient mood. “I’m having a ball, man!” he crowed. “This album has done so much for us. And it’s the first time that a true heavy metal single has made the US Top 10. You don’t even have dreams this crazy!”

DuBrow felt vindicated at last. “It’s real satisfying after hearing the same words all the time in the old days: ‘Quiet Riot? They’ll never make it!’ I have to laugh at that…”

He also claimed that success hadn’t affected him. “My friends treat me as if I’m a different person,” said. “But it’s their attitude to me that’s changed. Things haven’t changed in my head at all.”

But if this was true, it was only because Kevin DuBrow was always a star in his own mind. The “huge ego” that Banali speaks of was DuBrow’s default setting long before he had the No. 1 album to back it up. And with Quiet Riot’s success came a bigger platform from which DuBrow could shoot his mouth off.

As Banali says: “Kevin was, for better or worse, the single most honest person I’ve ever known. If he had an opinion, he’d verbalise it loudly and often. What most people only think of or whisper in private, Kevin would scream at the top of his lungs. That kind of honesty is rare, and it comes with a price – which Quiet Riot paid dearly.”

It was churlish of DuBrow to slag off fellow LA metal bands that had been signed to major labels in the wake of Quiet Riot’s success. Worse, it was just plain dumb of him to ridicule a figure as iconic and beloved as Ozzy Osbourne. By joking that Ozzy sang “like a frog”, DuBrow alienated many rock fans. Osbourne himself retaliated to DuBrow’s jibe when he met Rudy Sarzo by chance – and promptly decked him. But for Quiet Riot, the backlash did not end there.

By the summer of 1984, Metal Health had sold six million copies in the US, but Quiet Riot had become the most vilified band in rock’n’roll. And when follow-up album Condition Critical was released, Rudy Sarzo gave an interview that was effectively an exercise in damage limitation.

He described his fracas with Ozzy as “sad”, and insisted that DuBrow had been “totally misunderstood”. But there were other criticisms to answer. Quiet Riot’s decision to launch Condition Critical with a cover of another Slade song – DuBrow’s favourite, Mama Weer All Crazee Now – had been mocked by Nikki Sixx of Mötley Crüe, who claimed that Quiet Riot were no better than a bar band. Sarzo’s response was sharp: “Mötley Crüe did Helter Skelter, right? The only difference between us and them is that we had a hit with somebody else’s song and they didn’t.”

Sarzo was also quick to deny an allegation from Def Leppard’s manager Peter Mensch that Quiet Riot had already “peaked” and were “in trouble”. Condition Critical, Sarzo said, had “shipped gold right off the top of the box”.

As shit rained down on Quiet Riot, Sarzo refused to blame DuBrow publicly. “Even if Kevin hadn’t been so controversial,” he argued, “we still wouldn’t be liked as a group because people are jealous of the magnitude of our success.” But in private, both Sarzo and Banali were beginning to view their outspoken singer as a liability. And within a year, Sarzo would quit the band, replaced by a returning Chuck Wright.

Condition Critical sold three million copies: a huge success, but only half as big as Metal Health. Says Banali: “We knew there was no way anything could equal or surpass the sales of Metal Health. If Condition Critical was a failure, it was the kind of failure I could live with.”

But the next album, QRIII, was an outright flop, peaking at No.31 on the US chart in 1986. DuBrow remained defiant in the face of hostility towards Quiet Riot. “They must have run out of nails trying to crucify us,” he laughed. “We’re just one of those classic cases of ‘set ’em up and kick ’em back down again’.” He also stated: “There’s absolutely no one I need to prove myself to.”

But he was in for a shock. In early 1987, after QRIII bombed, DuBrow was fired from the band he’d founded and led for so long.

“It wasn’t the band that wanted him out,” Banali claims. “It was management and the label. But it took the band to make the change.” Another contributing factor was DuBrow’s excessive drinking and drug use. Banali admits: “We all indulged, but Kevin could be told nothing by no one, and his lifestyle choices had made it impossible for us to continue with him.”

Quiet Riot replaced DuBrow with ex-Rough Cutt singer Paul Shortino for fourth album QR in 1988, which also featured another new bassist in Sean McNabb. This, too, was a failure, and in 1989 the band split, with Banali joining W.A.S.P.. But within a year, Quiet Riot would be born again. And once more, it was Kevin DuBrow’s band.

DuBrow could not and would not give up on Quiet Riot. It had been his life for 15 years. So in 1990 he re-launched the band with Cavazo, ex-Rainbow drummer Bobby Rondinelli and bassist Kenny Hillery. And in 1993 he reached out to Frankie Banali.

The pair had spoken only once in three years, after Banali’s mother died and DuBrow called to offer his condolences. But when they talked again, DuBrow made it clear that he held no grudge about being sacked. He knew that was how the music business worked. Banali was persuaded not only to rejoin Quiet Riot, but also to manage the band. And as he says now: “It was the best decision I ever made, because Kevin and I became closer than even before.”

Together, Banali and DuBrow saw Quiet Riot through another 14 years, with just one break in 2003. After 1993’s comeback album Terrified, Kenny Hillery left the band. He committed suicide in 1996, aged just 26. Chuck Wright returned for 1995 album Down To The Bone, but in 1997 the Metal Health line-up was reunited. And as Banali explains, the catalyst was none other than Marilyn Manson. “Quiet Riot played at Manson’s after-show party at the Hollywood club Dragonfly,” Banali says. “So we invited Rudy to do a few songs, and it felt really good.”

The foursome stuck together for another six years, recording two albums, before Sarzo and Cavazo moved on – replaced in 2004 by Wright, once again, and guitarist Alex Grossi. And in 2006 came the last album that Kevin DuBrow would make, with a title that would prove cruelly ironic: Rehab. The album was recorded with bassist Tony Franklin, formerly of Jimmy Page and Paul Rodgers’ 80s supergroup The Firm, and guitarist Neil Citron. But when Quiet Riot toured in 2007, it was with Wright and Grossi.

The tour ended on November 4 in San Jose, California. “The show was great,” Banali says. “Vocally, Kevin was at the top of his game.” The next morning, Banali and DuBrow said their goodbyes at San Jose airport, Banali en route to LA, DuBrow headed for his home in Las Vegas. Banali recalls: “I said to Kevin, ‘I love you, my friend. Have a safe trip and call me when you land.’ He replied, ‘I love you too, my brother Frankie B.’ It was the last time we saw each other.”

In the days that followed, Banali spoke to DuBrow several times on the phone. DuBrow called on November 16 with an apology: he’d forgotten Banali’s birthday two days earlier. Banali said not to worry. “I assured him that it was fine because we had already celebrated a lifetime of birthdays together on and off the road.” But they never spoke again. On November 26, 2007, Banali received a call from his old friend Glenn Hughes telling him that DuBrow had been found dead at his home. He was just 52. “It broke my heart,” Banali says.

It was subsequently confirmed that DuBrow had died from a cocaine overdose. “His death,” Banali says, “was an accident of his chosen lifestyle.” But what angered Banali were the news reports that focused on the fact that DuBrow had died alone. “I think people make too much of that scenario,” he says. “Yes, the thought of it is tragic, but Kevin didn’t want to die. That was not part of his DNA. In the last years of his life, he was the happiest I had seen him since the glory days of Quiet Riot. He felt that all things were possible again. But sadly, it was not to be.”

Frankie Banali continued to lead Quiet Riot, with the blessing of DuBrow’s family, until his own death from pancreatic cancer in 2020. And during those final years, what mattered most was that Kevin DuBrow should never be forgotten. “I’m doing my best to keep Kevin’s memory alive,” he said. “Each time I walk on stage with Quiet Riot, I bring Kevin with me in my heart.”

Kevin DuBrow had lived to win. As he said in 1986: “I’ve experienced more self-glory than most of the world’s population will ever dream of.” And for all his faults, it was his leadership and gung-ho mentality that drove Quiet Riot all the way to the top.

As Frankie Banali said: “Kevin and I spent 27 years of our lives together in the same band. And even with all the problems that he and I had to deal with over the years, he was the best friend I ever had. I miss him every single day of my life."

The original version of this feature appeared in issue 9 of AOR Magazine, published in September 2013.

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2005, Paul Elliott has worked for leading music titles since 1985, including Sounds, Kerrang!, MOJO and Q. He is the author of several books including the first biography of Guns N’ Roses and the autobiography of bodyguard-to-the-stars Danny Francis. He has written liner notes for classic album reissues by artists such as Def Leppard, Thin Lizzy and Kiss, and currently works as content editor for Total Guitar. He lives in Bath - of which David Coverdale recently said: “How very Roman of you!”