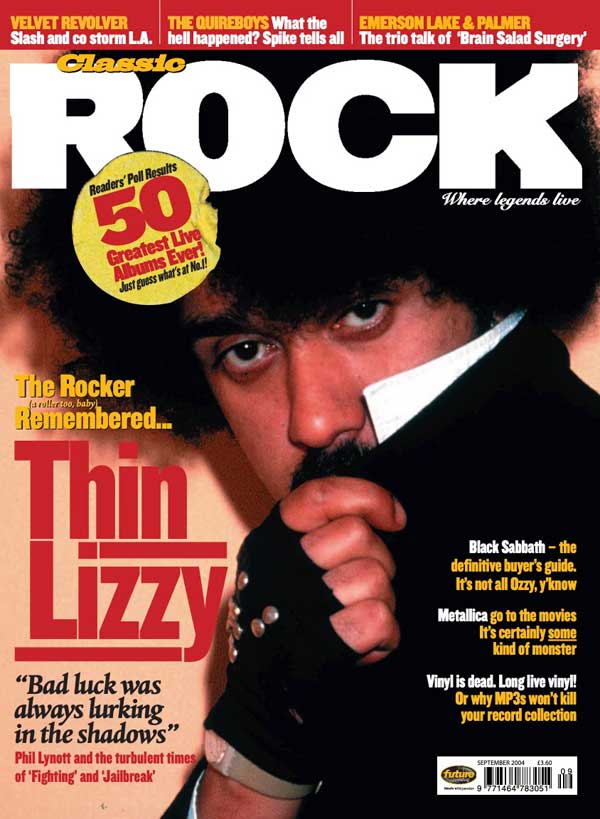

By 2022, there were two versions of The Quireboys operating at the same time. Two years later, frontman Spike launched a new version of the band, while the "other" Quireboys, led by guitarist Guy Griffin, eventually reemerged as the Black Eyed Sons. It was always thus in the ever-fractious, ever-chaotic world of one of the UK's greatest rock'n'roll bands. In 2004, as The Quireboys released their Well Oiled album, they told Classic Rock their riotous, booze-soaked story.

For the first of what would be many times this afternoon, Spike leans across our table at London’s Kensington Gardens Hotel and addresses me in friendly, conspiratorial yet unmistakably alcohol-charged tones: “You want the story of The Quireboys?” he retorts, slurring slightly. “That’s easy. We met all these journalists – Geoff Barton, Mick Wall, Krusher – and none of them had any work to do or any drugs to take. So we created a rock’n’roll band. If it wasn’t for The Quireboys, all of youse bastards wouldn’t have jobs. We paid for all your booze, birds and drugs, and still to this very day all you bastard journalists do is slag us off.”

Also for the first of numerous occasions this afternoon Guy Griffin winces and raises his eyes to the heavens. Better-known to his mates as Griff, The Quireboys’ guitarist is by now aware that nobody will change Geordie barfly Spike, nor is the singer likely to dilute his opinions for public consumption after having sunk a few. But then we wouldn’t want it any other way.

The Quireboys have existed on and off since 1985, having formed shortly after Newcastle-born Jonathan Gray had relocated to London. He was laying paving slabs outside Buckingham Palace when workmates dubbed him Spike, because of his Rod Stewart-style coiffure. The nickname stuck, although, strangely when one considers the style of music that he would sing for almost the next two decades, Spike wasn’t a fan of either Rod or The Faces.

“To me, Rod Stewart was Sailing and Maggie May – all the hits,” Spike says dismissively. “It was always the Rolling Stones, Humble Pie and old soul stuff that I loved. Plus I’d been trained on the classical guitar when I was a kid, so I wasn’t even a singer in those days.”

As I discover during the next hour-and-a-half, Spike has a bagful of anecdotes, and his transition from Ralph McTell-fixated folkie to gravel-throated aspiring rock frontman is no exception. By then Spike had long since met guitarist Guy Bailey in the latter’s local pub, and he eventually ended up sleeping on the floor of Bailey’s flat for two years. One fateful evening, much to the astonishment of his flatmate, Spike produced an acoustic guitar and three songs were written (Seven O’Clock, I Don’t Love You Anymore and Misled), all of which eventually appeared on the first Quireboys album.

Bailey and Spike were playing an early gig at a community centre in Brixton, London, when the latter broke a guitar string and had no replacement. “Guy went: ‘You sing into the mic – just have a go’. And nobody knew what would come out,” Spike recollects fondly. “It was crap, like, but that was the beginning of the band.”

In a roundabout way, the group’s name also originated at the same central London building site, where Spike had also blagged Bailey a job. Having watched The Choirboys, a movie about New York cops, the night before, a chat about how cool a name it’d be for their new band was rudely interrupted.

“We worked with all these Italians who went: ‘The Choirboys? You’re the fucking Queerboys’. Funnily enough we preferred being The Queerboys. It was meant as a laugh, but it got us banned from all the universities, everywhere.

When bassist Chris Johnstone departed briefly in late 1985, the band’s rhythm section was completed by Nigel Mogg (nephew of UFO singer Phil Mogg) along with existing drummer Coze. Johnstone did return, but as the keyboard player. Nigel had been a page-boy at his famous uncle’s wedding, and craved his own shot at rockstardom.

“I’d met Guy and Spike at Dingwall’s one night. They’d said I looked good and wondered if I played bass,” Nigel Mogg recalls.

Coincidentally, he did. Pete Way, UFO’s four-stringer, had already kindly given Nigel a bass of his own. “It was a Thunderbird,” Nigel grins now. “I played it at a few gigs – ’til Cliff Evans from Tank asked for it back. It turned out that Pete had apparently borrowed it from Cliff’s instrument shop, so it wasn’t even his to have given me.”

“Nigel joined the band because he looked good,” Spike points out helpfully. “He couldn’t play – he still bloody can’t! – but he’s Mr Fashion. It wasn’t ’til Griff joined that The Quireboys became a proper band.”

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. For a while, Phil Mogg even became the group’s manager, making phone calls on their behalf and introducing them to industry figures like photographer Ross Halfin, who handled their first-ever photo session (“Ross was just as annoying then as he is now,” Nigel says).

The group kept themselves visible, becoming the Marquee’s unofficial ‘house’ band. In London and beyond they would open for anybody and everybody, and did so for a list that includes Johnny Thunders (“He treated us like shit, but introduced me to mixing Bailey’s liqueur with cognac,” Spike recalls), Yngwie Malmsteen (“He was furious that Sounds had printed a full-page picture of me, and a postage stamp-sized one of him” – Spike) and the Cherry Bombz. Then during a Queerboys Friday night headline residency at The Marquee in June 1987, Guns N’ Roses walked in.

“They were playing the following weekend and had come to check the club out,” Nigel recalls. “We met them, they thought we were good, and they were great too. I hung out with Axl, Slash and Duff at their hotel, and we struck up a friendship.”

The Queerboys’ run of good fortune brought them the offer of a spot on 1987’s Reading Festival bill, where they had the opportunity to appear alongside Alice Cooper, Magnum, The Stranglers, FM, Quo and Zodiac Mindwarp. But there was a condition: they had to change their name.

“We became the Pretty Girls for a very brief time,” Nigel divulges, “before the idea of the different spelling came up. With hindsight I wish we’d stuck to our guns. Nobody would bat an eyelid at a band called The Queerboys these days.”

As Spike relates unexpectedly, the group actually decided to call it a day, but then Phil Mogg came up with his biggest coup. “I’ll never forget it,” the singer beams. “We were in the middle of what was gonna be our very last rehearsal, when Phil walked in with these two bags full of booze. He’d not only got us the gig opening for Guns N’ Roses and Faster Pussycat at Hammersmith Odeon, but the whole bloody UK tour.

“UFO were so good to us,” he continues. “Guy Bailey didn’t even own a guitar at the time, so they lent us loads of equipment. When Duff [McKagan, GN’R bassist] saw we had UFO’s crew and flight cases he said: ‘Fucking hell, you’re professional’. How wrong he was!”

Nevertheless, the attention The Quireboys were receiving hadn’t gone unnoticed by a young guitarist called Ginger. Having recently arrived in London from Newcastle, he lacked the funds to buy a ticket for the Hammersmith gig so he employed extreme methods to gain admission.

“I went to a nightclub [Buttz ’N’ Spike’s] that Spike used to run and told him: ‘Look, I’m your new lead guitar player’. They didn’t need a new guitarist, but Phil Mogg had already suggested getting one,” Ginger told us in March 2004. He also claimed that he was eventually booted out of The Quireboys for being “too wild” for them. Spike and Nigel remember things very differently, however.

“That’s absolute bollocks,” Spike seethes. “Ginger’s still one of my best friends, but I’m a Newcastle United fan and he’s a fookin’ Mackem [nickname of arch rivals Sunderland]. Our problems weren’t about drugs, drinking or women, it was because he supports Sunderland. Man, I’m being deadly serious with you.”

What Ginger actually told Classic Rock was that he was “well into my drugs, but the rest of The Quireboys only drank. Which was funny, as months after I left they were all in the Betty Ford Clinic with coke addictions.”

“He was also supposedly too wild for The Throbs,” Spike chuckles, referring to Ginger’s even shorter tenure with the hard-partying New York band who invited him aboard after his Quireboys sacking. “They thought they were getting Nigel, but they’d rung the wrong guy.”

“That’s quite true,” Mogg says. “Ginger was apparently so drunk while they were trying to make their album that they’d had enough. They took him to the airport, went out to a bar to celebrate getting rid of him, and by the time they got back Ginger was waiting outside their apartment. He wouldn’t leave.

“For Ginger it was all new,” Mogg continues. “He’d never been in bands that had had much attention. We were used to headlining shows and signing a few autographs. In a sense he had it on a plate, because he missed out on our transit-van years. Ginger was the last one in, so there was also some piss-taking. He also had this annoying habit of pretending to be drunk to seek attention from the ladies. But, God bless him, he was trying.”

“When you’ve met people like Mick Jagger or Steven Tyler, who are up here,” Spike says, his hand above his head symbolising the very pinnacles of excess, “and Ginger’s down here [the same hand is now at knee level], I mean… Just don’t do it, man. Please, it’s embarrassing. You wanna talk drugs? I’ve taken more than Ginger’ll ever do, but I don’t go on about it all the time.”

“But there’s nothing glamorous in talking all the time about drinking or taking drugs,” an anxious-looking Griff chips in, forgetting for a moment that we’re here to promote a new Quireboys album called Well Oiled.

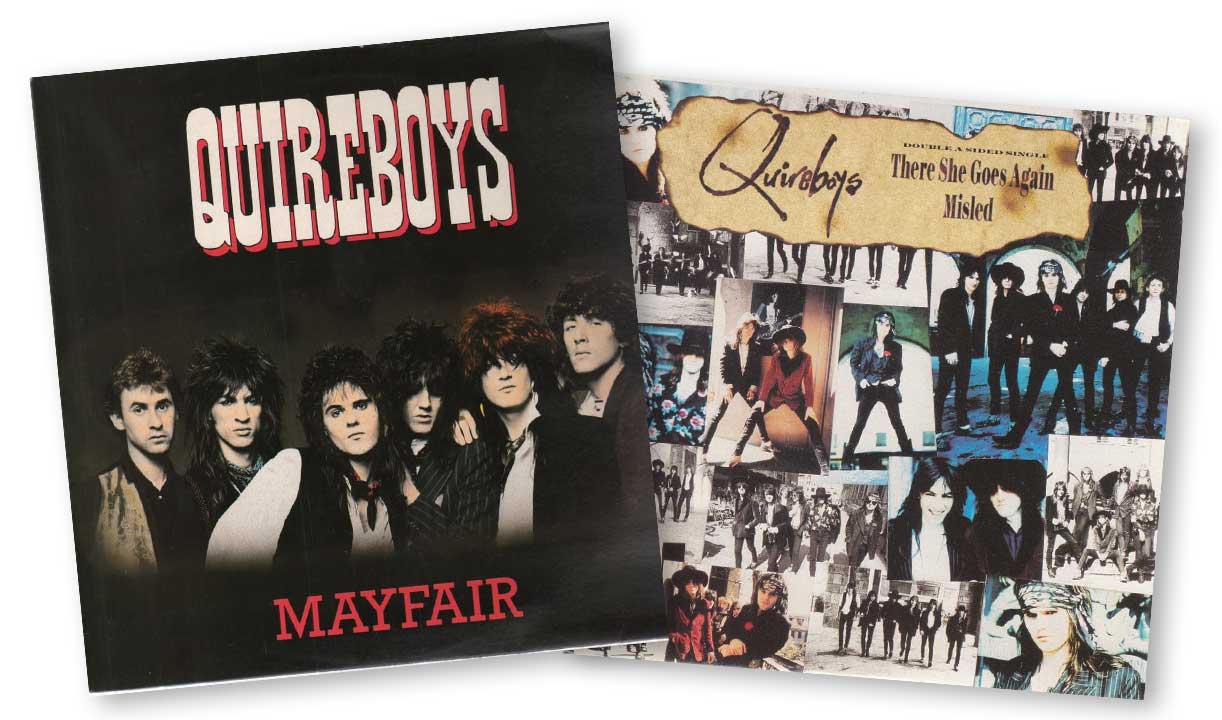

With Ginger still on board, and Marquee Club boss Bush Telfer booking the band’s shows, The Quireboys signed to Survival Records, a feeder label for EMI, for the princely sum of £18. They enjoyed success with their first two singles, Mayfair and There She Goes Again, although in typically ramshackle fashion the latter was written just six days before it was recorded. The group also had a meeting in Cardiff with Larry Mazer, an important US manager (who, ironically, now looks after The Wildhearts). Incredibly, while Mazer was making them all sorts of promises they all fell asleep – Ginger face-down in a plate of chips.

“But we were on a roll,” Spike points out proudly. “By then we’d sold out The Astoria and The Dominion [in London] without a record deal. That’d never happen today.”

The band played the Reading Festival again in 88, along with Iggy Pop, The Ramones, Meat Loaf, Uriah Heep and Starship, although Ginger was arrested en route and almost failed to materialise. Also, by this point Sharon Osbourne was considering adding The Quireboys to her management roster.

Ginger’s aforementioned dismissal took place in January 1989, following an American tour on which he had consistently misbehaved. “Sharon had probably seen Ozzy’s dark side in me,” Ginger later theorised. “I knew that something was up, because nobody would speak to me on the flight home.”

On the band’s return to the UK, ex-Cradle Snatchers/Feline Groove guitarist Guy Griffin joined, while drummer Coze was also being shown the door.

Griff’s first meeting with Sharon Osbourne was a memorable one: “I was extremely nervous, because I didn’t know whether or not I was in the band – Guy Bailey hadn’t wanted me,” he explains. “Sharon asked me: ‘Are you a cunt?’. I said that I didn’t think so, and she replied: ‘Good. If you’re not a cunt then you’re in the band; when you become one, then you’re out’.”

Even in those early days, Sharon was known for her ruthless management style. Indeed, Chris Johnstone would later claim that Sharon once purposely placed Bailey at the end of the line-up in a band photo session so that he could be cropped out of the picture when she’d found a reason to sack him.

Spike grins sheepishly when he’s reminded that he once told an interviewer: “Anyone who can get [ex-Runaways guitarist] Lita Ford a platinum album has to be alright.” These days he has nothing but praise for Ozzy’s missus.

“I gather she’s a completely different person now, but when I knew Sharon she was one of the nicest people I’ve ever met,” he says. “There’s no bad feeling from me. When she had no time to work on us any more she introduced us to loads of other managers, instead of just dropping us in the shit.”

If Spike is to be believed, he received the news that The Quireboys had been promoted from Survival to EMI by letter. “The fee was just a pound – how the fuck does that happen?” he ponders, still mystified. “Rupert Perry [head of EMI] rang to talk about the deal, but it was the morning after a Buttz ’N’ Spike’s club night and I fell asleep on the phone. He couldn’t cut me off to speak to anyone else for five bloody hours!”

Ian Wallace (of Bob Dylan fame) filled the drum stool when The Quireboys flew to LA to record their debut album. The intention had been for Ron Nevison (Led Zeppelin, Bad Company, UFO) to produce the sessions, but he wasn’t available when the band wanted him (he did, however, handle the mixing). At the last minute, Rod Stewart’s producer George Tutko and guitarist Jim Cregan flew into London to make their own sales pitch. “Afterwards, everybody went to Buttz ’N’ Spike’s and they said: ‘C’mon, let’s drink’. We had to pick them up off the floor,” Griff laughs. “In fact there was a party atmosphere throughout the whole album.”

Each time the doors to LA’s Cherokee Studios swung open, a stream of models and musos would drop by to hang out. When Rod Stewart and Paul Young both came on the same day, Spike was mortified that Stewart would hear his guide-vocal recordings.

“Tom Petty and Don Henley [Eagles drummer/vocalist] also came down,” Spike recalls. “You’ve got no idea what it was like with so many famous people around. I asked this guy with long black hair: ‘What do you do, mate?’ He said he sang. I said: ‘Have you been doing it long, and do youse do well?’. He nodded. When I asked what his group was called, he said Journey. It was Steve Perry, and I’d never fucking heard of him!”

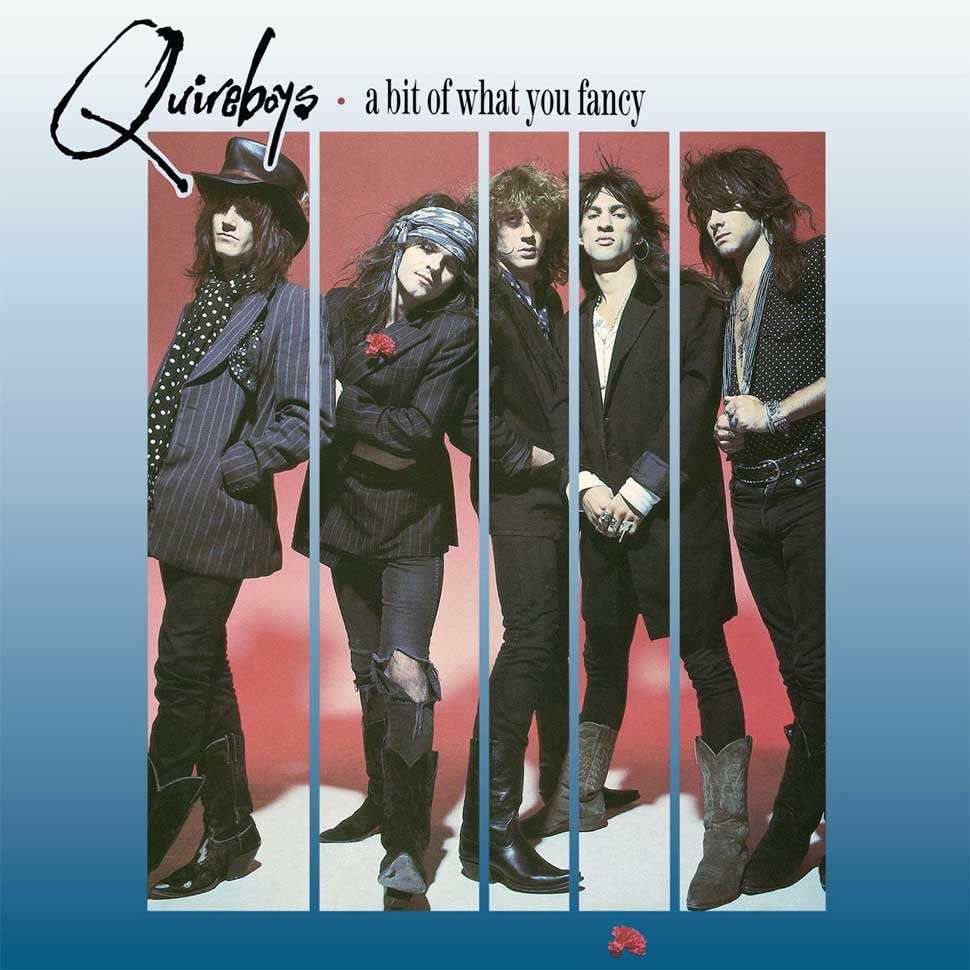

Titled A Bit Of What You Fancy, The Quireboys’ album peaked at No.2 in the UK chart following its release in February 1990, its sales stoked by three Top 40 singles (Seven O’Clock, their signature Hey You, and I Don’t Love You Anymore). However, there remained a certain cynicism in sections of the British music press who weren’t out boozing with the band, with those writers mockingly referring to the group as the Rolling Quirefaces and suchlike.

“It was annoying. We weren’t the only band to have easily identifiable influences,” Mogg complains. “Thunder were Bad Company and Free rolled into one, and they never took the stick we did. Of course we were surprised to have all those hits, but we were on a roll. The shows were great, so were the songs, and we also had the right manager and record company to make them work for us.”

The Quireboys certainly emerged as leading lights of a newly energised UK rock scene, alongside the likes of Dogs D’Amour, The Almighty, FM and Little Angels. “Yeah, but Little Angels were complete shite, weren’t they?” Spike says with a malicious smile. “C’mon, why did Michael Lee [Angels drummer, who eventually played with The Quireboys] leave them? Because they were the worst band I ever saw in my life.”

With ex-Lone Justice man Rudy Rickman completing the touring line-up, The Quireboys’ image became inextricably linked with their love of booze; even their stage set was designed to look like a pub. “We wanted the beer pumps to work, but it was too time-consuming to have set up,” Nigel remembers fondly.

Indeed, most of the horror stories you heard about the band were true. I once spent an evening with them during a road report in 1989, and while checking out of the hotel the following morning found myself saying goodbye to a band member who was being taken to hospital to have his stomach pumped.

“That would probably have been Guy Bailey,” Nigel ponders. “The drinking made him ill twice. He even missed some shows due to dehydration. We all went to visit him in hospital. And he was still wearing his cowboy hat.”

“There were times when Guy wouldn’t even finish the gig,” Spike adds. “You’d come off stage all sweaty and he’d be there in the bar: ‘Good gig, lads’.”

The big time had finally arrived for The Quireboys – who had gone through 10 tour managers in one single trek before hiring Led Zeppelin’s legendary Richard Cole for a whopping £4000 a week. While out supporting Whitesnake on 1990’s Monsters Of Rock circuit (along with Aerosmith, Poison and Thunder), Cole had attempted to impress upon the band the importance of being sober while in the presence of the on-the-wagon Aerosmith. So there was considerable unease when a dishevelled-looking Spike shuffled into the hotel lobby after a night on the tiles and bumped into a breakfast-bound Steven Tyler.

“He asked how we were enjoying the tour, and I said everything was great and that I was really looking forward to Switzerland,” Spike says with a roguish grin. “He replied: ‘Spike, we’ve been in Switzerland for the past two days’. But we had a good laugh about it. In fact the next day we were in Amsterdam and he asked me to buy him some gear – just so he could smell it. I told him to get his own fucking drugs, I don’t smoke dope. What made it funnier still, three girls then came running down the street, blanked Steven and asked for my autograph. Classic!”

The same year, The Quireboys also played Spike’s dream gig, supporting the Rolling Stones at Newcastle United FC’s stadium St James’ Park. There was also another memorable festival spot, in Germany with David Bowie. “We were dying in front of his audience,” Spike recalls. “So I told ’em: ‘It’s not my fault you lost two world wars and one World Cup’. We went down great after that.”

Outside of Europe, the group re-christened themselves the London Quireboys, due to the existence of Australian band The Choirboys. “We offered them £20,000 to change their name,” Spike reveals, “and they turned us down. Then three months later they got dropped. Bet they wished they’d taken our fucking money.”

The London Quireboys gigged hard across America to promote their debut album, playing with LA Guns in the clubs and opening for labelmates Heart in stadiums. Spike recalls one particular female US fan vowing to resist Nigel Mogg’s ardour until she’d heard his band on the radio. Her mood towards him warmed considerably en route to an after-show party when Seven O’Clock blared out of the car radio.

But there was little balance in their lives: in a single week the group headlined a sold-out Budokan in Tokyo, then played to 200 people in fancy dress in a US club. The touring had played havoc with everyone’s personal lives, resulting in both Spike and Bailey splitting up with their long-term girlfriends. It also began to influence the group’s material: “We started writing all these fucking depressing ballads,” Spike recalls. “It was not a good time.”

After Sharon Osbourne dropped The Quireboys in April 1992, the group met several potential new managers before deciding to go with AC/DC’s Steve Barnett. Spike has already expressed his admiration for Sharon, but a knee-jerk bitch-fest at the time left Nigel experiencing her legendary wrath.

“Spike and I went out for a drink after she told us, and some girl that I didn’t know was with us,” Nigel remembers. “Next morning I found out she was the Osbournes’ nanny and had heard all my ranting and raving. Sharon rang, called me a fucking little cunt and threatened to cut off my balls and shove ’em down my throat. We’ve not spoken since.”

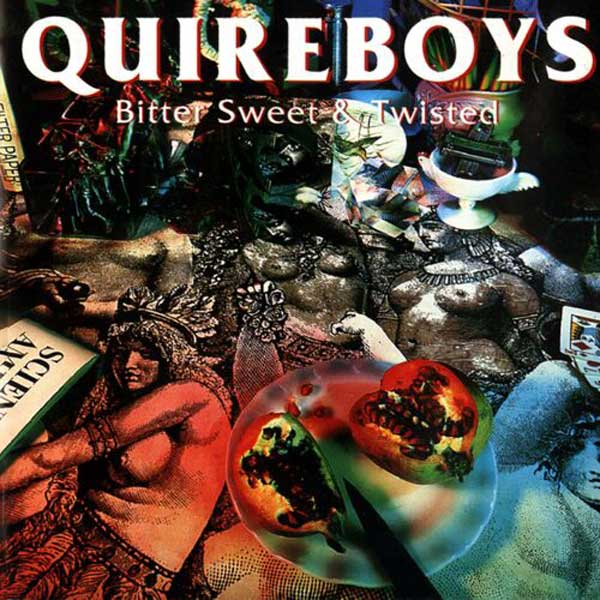

By that point the band had already been working on their second album for a year. The headaches they faced up to during sessions for what became the aptly titled Bitter Sweet & Twisted could fill a book on their own. In a nutshell, the band decamped to Ireland and wrote 18 songs, which were to be recorded with Ron Nevison. Then, at Sharon’s suggestion, the producer’s job went to Bob Rock instead. Except that Rock was still beavering away on Metallica’s Black Album.

Seven months later The Quireboys finally began work at Little Mountain Studios in Vancouver. But now the record company wanted Spike to write some new material with Bryan Adams’ songwriting collaborator, Jim Vallance.

Bob Rock then decided he needed a holiday, so Spike and Bailey accompanied him to Hawaii. At George Benson’s studio in Maui, Guy’s amplifier blew up and there was no replacement on the island.

The entire circus moved on to London, where Rock tried unsuccessfully to mix what they’d recorded. Just as everyone decamped back to Vancouver.

Meanwhile, Sharon and EMI’s Nick Gatfield both severed their responsibilities to the band, whose hotel bills alone now amounted at £4000. To cap it all, Rolling Stones producer Chris Kimsey was then brought in to work on some extra tracks.

“We were being whisked all over the world to work on this record,” Griff seethes, “and then they sat on it for a year.”

“In Ireland, at the start, we recorded the album in two days flat,” Spike says. “It was fucking great. I wish I still had a tape of it.”

The group had vehemently opposed working with outside writers such as Vallance, yet Griff shamefully admits that they backed down after EMI offered them an extra $30 per day toward their living expenses.

“Jon Bon Jovi had also sent some songs for The Quireboys to do,” Spike adds candidly. “They were fucking shit. He didn’t have a clue. And I’d tell Jon that to his face. Jim Vallance was a lovely bloke, but he wouldn’t let me smoke. I looked at Guy Bailey and knew we had to get the fuck out of there as quickly as possible, so we wrote the song [The King Of New York] and were gone in two minutes flat. To me it’s shit. I only wrote it to get a fucking cigarette!”

Nigel Mogg reckons the choice of Bob Rock was also completely wrong. “I didn’t like any of the records he’d made,” he says now. “How do Mötley Crüe, The Cult and Metallica relate to us? And waiting around for him for half a year, which then became nine months, was quite ridiculous.”

Preceded by the single Tramps & Thieves, the Bitter Sweet & Twisted album was finally released in March 1993, just as a musical revolution was announcing itself: Nirvana, Alice In Chains, Soundgarden et al were about to wipe the slate clean; even Ginger was starting to do well with his band The Wildhearts.

Bitter Sweet… reached only No.31 in the chart. It spawned another Top 40 single in the shape of Brother Louie, but by then, after all the waiting, the group were just happy to have the damned thing in the racks. EMI felt differently, however, and released The Quireboys from their contract.

“Parts of that album were great,” Mogg considers now, “others were strung out and abysmal. If you wait for something for six months, you end up losing interest in it yourself.”

A temporary form of salvation was at hand. The Quireboys played some more shows with Guns N’ Roses, this time on the Scandinavian and German legs of the latter’s Use Your Illusion stadium tour.

“That band have always been good to us,” Griff acknowledges. “We’d just been dropped by EMI and had no idea what to do next. Then Axl calls to ask if we’ll be their special guest. It turned out that he was a big fan of King Of New York, which was from an album that hadn’t even been released in America. I believe he bought an import copy. We had absolutely no money, so we ended up getting the ferry over.”

Nigel, who lives in Los Angeles these days, still remains friendly with the ex-Guns/current Velvet Revolver duo of Duff McKagan and drummer Matt Sorum, although he says he has “not seen Axl for years, and the others [ex-GN’R members] really don’t like talking about him”.

Bitter Sweet & Twisted went platinum in Canada, where, along with Europe and Japan, The Quireboys toured. But disillusionment set in as attendances at the band’s shows dwindled.

Last seen in his own band Dog Kennel Hill, Guy Bailey left, telling his bandmates, according to Spike: “I can’t tread the boards anymore, dear.”

Griff admits that the group were “getting a bit sick of each other” by this point. And the simmering frustration within the band blew up in everybody’s faces when Spike stormed off the stage at a festival in Belgium, telling his partners: “Fuck the lot of youse. I’m out of here.”

“So many factors were working against us,” Griff muses now. “I was only 22 when we split up, but we’d become as unfashionable as it was possible to get. Music had completely changed, and we weren’t equipped to deal with what was going on.”

“We couldn’t get another record deal, and there seemed little point in flogging a dead horse,” Mogg sums up regretfully. “Stepping down on to an indie label wasn’t for me. There was a tour with Darrell Bath [taking Griff’s place], but Guy Bailey was still there so I wanted nothing to do with it. Towards the end, Guy and I didn’t get on, and I still attribute a lot of our in-fighting to his pessimism and lack of enthusiasm. In fact Guy even failed to turn up for a few of the last shows, so I was proven right.”

Spike went on to form God’s Hotel with ex-Burning Tree drummer Doni Gray, and that band’s album took four years to come out. As well as recording a solo album of R&B and soul songs, Spike also turned down the chance to front Snakepit, the band formed by guitarist Slash after his departure from Guns N’ Roses – understandably a subject he’s now somewhat tired of talking about.

“Let me show you what happened,” he says, thumbing through a wallet that still contains a membership card for Los Angeles ‘hairspray’ hangout The Cathouse, and finally producing a photograph of his son. “Slash is the fucking guy, but I was living in Toronto at the time and the timing wasn’t right.”

In early 1995 Spike reunited The Quireboys for very personal reasons. With his father on his deathbed, Spike assembled a makeshift line-up that included members of The Almighty and Honeycrack to play a one-off concert at Newcastle’s Mayfair.

“My dad had lived for going out on tour with The Quireboys,” he says sadly. “Danny [Bowes] and Luke [Morley] from Thunder also came up and did the show. But the week before it took place he passed away. He’d have loved it.”

Spike also made headlines with his involvement in Michael Schenker’s departure from UFO. The pair had clashed backstage at UFO’s show in Newcastle in November 2000, a violent confrontation that caused guitarist Schenker to hit the bottle all the following day and deliver a quite horrendous and now legendary swansong at Manchester Apollo.

“Schenker had been ranting and raving at me for no reason at all,” Spike says. “He left the dressing room, and then came back in saying he was gonna kill me. He launched himself at me, so I put him on the floor – and I had a broken leg at the time! I was in the wrong place at the wrong time. But the bloke’s absolutely mental. When the police came, one of them was a Quireboys fan. They were still gonna take me away, ’til Phil Mogg said everyone in the room would swear that Schenker attacked me first.”

With The Quireboys just a fading memory and a lingering smell of stale booze, the rest of the band pursued a diverse array of projects. Mogg and Griff had a short-lived Los Angeles band called Blood From A Stone, before Guy formed Glimmer, who in 1999 released an album for Atlantic Records. Nigel formed his self-styled ‘glambient’ group Nancy Boy with vocalist Donovan Leitch (son of 60s star Donovan) and guitarist Jason Nesmith (son of Monkees guitarist Mike). The bassist has also since worked as a model, journalist and photographer, and even had his own jeans company.

When Spike decided to revive The Quireboys in 1999, even Nigel Mogg admits to an uncertainty over whether there would still be an audience. However, the knowledge that his nemesis Bailey would not be involved, and then two sold-out shows at London’s Garage, convinced him to play on the band’s comeback album This Is Rock’N’Roll.

“At first it was gonna be a solo project, but then Nigel came on board, and Sanctuary Records were stupid enough to give us tons of cash,” Spike grins. “So now it’s The Quireboys again. And with bands like Jet around there are a lot of younger people coming along to check us out.”

The reunion was cemented on 2002’s Monsters Of Rock tour (headlined by Alice Cooper), for which they were joined by Jason Bonham on drums. For the enjoyable 2004 Well Oiled album, issued by their new label SPV Records, they were joined by former Red Dogs guitarist Paul Guerin, keyboard player Keith Weir and drummer Pip.

By then Nigel Mogg was keen to dismiss the group’s reputation as flaky piss-heads. Okay, they still enjoyed a drink or 32 on stage, but it was then fairly recently that they were forced to cancel a show, and that was down to the bassist’s visa problems rather than being alcohol-related.

“Give Spike a glass or two of cider and he’ll talk bollocks all day,” says a slightly irritated Mogg. “He’s never pulled a show in his life. If the things they said about us were true we’d either be alcoholics or dead. It’s harder than ever for a band like us to survive. We sort out the record deals and manage ourselves, we also run the merchandising and website [www.quireboys.com]. With six people’s lives to run you’ve gotta be organised. We’re far more together than people think. Plus we’re older now and can’t take the hangovers as well, so we’ve learned to pace ourselves.”

Some 18 years after they first got together, The Quireboys were still regulars on the European touring circuit, and supported Whitesnake on their 2004 UK tour. “To some we’re still a Faces rip-off band, but the fans come to see us,” Mogg shrugs. “People actually thank us for still being around. That’s gratifying, and as long as it continues then we will be.”

But was it realistic for The Quireboys to keep on going even if they were to find themselves still stuck in the clubs, with the larger venues they filled in the past out of their reach? “We play three-chord rock’n’roll,” Spike shrugs. “Do you think we’ve got a fucking plan? But it’d be a crime to stop this band. We’re still packing them in in most places. We’ve blown fortunes, but we’ve done it in style. We’re all about having fun. Man, if you’d have been with us in Milan last week you’d definitely have got a shag.”

Before calling time on our chat, finishing our drinks and going our separate ways, I asked whether the sole reason The Quireboys were still rocking and rolling was because that was all they knew how to do. Spike gazed at me with playful indignity across his glass of cider, before all around the table erupted with one final burst of inebriated laughter when he replied: “Ah, that’s bollocks,” grinning broadly. “If you ever want any crazy paving done, I’m your man.”

This feature was originally published in Classic Rock issue 70 (September 2004). A new Quireboys album, Wardour Street, was released in 2024.