The world into which Radiohead released the monolithic OK Computer didn’t much resemble the one that we inhabit.

Just 19 days before the record’s initial unveiling in Japan, New Labour roared into power in the UK with a massive majority, following 18 years in the wilderness and successive periods of cruel Tory austerity. Riding a wave of optimism, the incoming party promised that things could only get better. The new PM, Tony Blair, was once in a punk band, commentators and acolytes assured cynics. Meanwhile, ‘Girl Power’ was dominating the UK pop charts, mobile phones were largely for playing Snake on, and the internet was something you accessed for a limited time courtesy of the direct marketing genius of AOL trial discs. Even then, it was rudimentary at best.

By their own already well-established curmudgeonly standards, the Oxford five-piece resolutely stood apart from what was going on elsewhere. The era of ‘Cool Brittania’ might have swept up a few champagne socialists, but Radiohead saw something altogether more terrifying coming down the pike.

Entering into public consciousness as angst writ large, the songs of OK Computer were fretful, and mistrusting of technology, politics, and the modern world. As the oncoming unknown of a new millennium soon loomed, Thom Yorke and cohorts were questioning where we were headed long before anyone else copped on. It introduced a colourful cast of characters and miscreants, from nauseating girls with Hitler hairdos to otherworldly superheroes who survived aviation disasters. As the cultural mainstream leaned into all things dayglo and disposable, OK Computer instead captured the unerring darkness, disconnect, isolation and paranoia underpinning the margins.

Had they been so inclined, this would have been an opportune time for Radiohead to cash in. Although nothing quite hit the heights of crunchy breakthrough single Creep off 1993 debut album, Pablo Honey, the band’s second album, The Bends, was a major success and made significant artistic strides forward, albeit ones still rooted in guitars-first introspection. Having earned the licence to try, with OK Computer, they were determined to strike out and do something entirely different. In the process, they would become something different too.

Capitol Records, the group’s US label, feared it would be tantamount to commercial suicide, downgrading their previously projected sales forecasts of shifting two million units to just a quarter of that. Although slightly more optimistic murmurings were made by the UK arm of EMI, the perceived lack of another Creep seemed to be the prevailing cause for concern.

They needn’t have worried.

It was on September 4, 1995, when the seeds of all this uncertainty were initially sown. Avant-garde legend Brian Eno invited the band to contribute a song to the War Child charity compilation, The Help Album, in aid of the devastated territories of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The catch was that all artists involved had to record their offering in a single day.

Enlisting the services of engineer Nigel Godrich, having worked with him on Black Star and some of the B-sides for The Bends, the band embraced the challenge and nailed the job in five hours. The resultant song, Lucky, would light the way ahead, eventually becoming the penultimate track on OK Computer. Buoyed by the thrill and euphoria of this new experience working with Godrich, a lasting and enormously fruitful partnership was formed.

But for all its eventual grandiosity, the record took shape in earnest in humble surroundings. Having freshly wrapped up a Stateside tour with the behemoths of R.E.M., Radiohead were invited back out as guests of Alanis Morrissette, whose debut album Jagged Little Pill was fast on its way to selling almost 19 million copies worldwide in 1996. Just before the tour kicked off, the band retreated to the countryside in Didcot, setting up in their rehearsal space, Canned Applause.

But for the sound of some mooing cows and birdsong in the sweet summer air, it was just the five members, the producer, and nobody or nothing else around for miles. The isolation would prove to be the perfect setting for the spirit of the emerging songs, and in those initial sessions, further groundwork was laid for an experimental record that looked on with anxious apprehension at the outside world.

Days after the Alanis tour finished, the band entered St. Catherine’s Court, an Elizabethan manor house in Bath, owned by actress Jane Seymour, to resume recording. Far from the relative spit and sawdust of the apple shed in Didcot, these sessions were recorded in a ballroom, surrounded by Medieval tapestries and wooden everything, capturing the sound beautifully. It was allegedly haunted too. Of course.

“People had claimed they had seen what they thought was my [dead] mother in a big blue dress walking through walls to go into the bathroom,” Seymour told writer Andy Greene. “Clearly, that was obviously odd. We had séances. We got people who specialise in that kind of thing to wander around the house.”

Radiohead's vocalist attested to the eeriness personally. “The ghosts would talk to me while I was asleep,” Yorke claimed. “I got really spooked while recording the vocals for Exit Music (For A Film). It felt like someone was standing next to me.”

Nigel Godrich, however, laughed off any suggestions of supernatural goings on as all a bit “Scooby-Doo.”

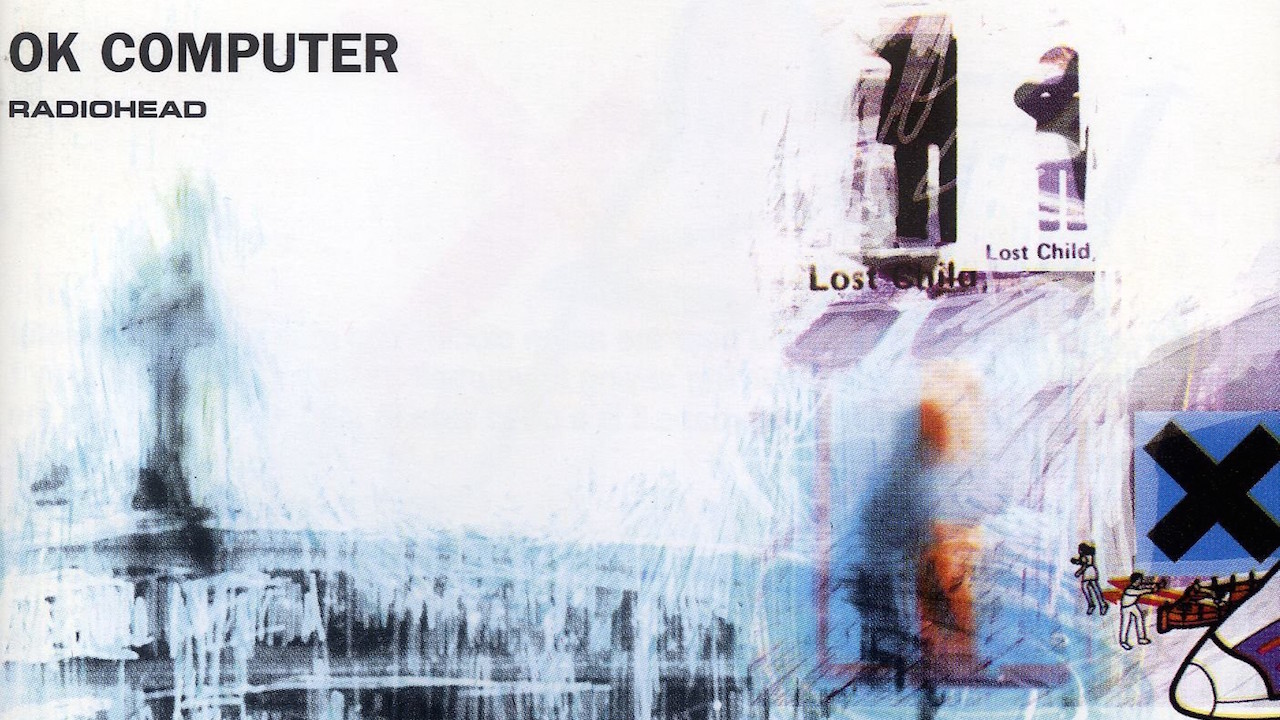

As the new songs began to coalesce, Yorke and artist Stanley Donwood worked to created the album’s distinctive blue-and-white artwork, pulling together digital collages of found items, scribbles, warnings, symbols and abstractions in English and Esperanto, with everything looking slightly smudged, foreboding, and evocative all at once.

“I got the completely mistaken idea that white was the colour of death,” Donwood reflected in 2017. “I was quite a morbid character.”

Morbidity and mortality threaded all through the record lyrically. Opener Airbag revisits Tom Yorke's fear of cars having survived a crash a decade prior. Mournful lead single Paranoid Android deals in themes of insanity and violence, mixed in with some anti-capitalist sentiment. Subterranean Homesick Alien speaks of a Clo

se Encounters Of The Third Kind-style desire for abduction, thanks to feeling othered, and the failure to fit in. And those are just the first three songs. All through the record there’s prescient themes of mental health and a litany of societal ills, predicated on the idea of the modern world hurtling rapidly towards ruin. To say that it’s a collection of songs ahead of its time is an understatement.

That’s embodied in one of its most striking moments, also one of its most unconventional. On Fitter Happier, Thom takes a backseat in favour of ‘Fred’ – the robotic voice used by Apple Macintosh machines in the ‘90s to convert text into speech – reeling off a host of mundane ways one could live life better, including everything from eating well to driving safely and being kinder to insects. The emotionless, synthetic delivery lends the advice a chilling quality: ‘like a cat, tied to a stick, that’s driven into frozen winter shit.’

Given what’s transpired in the 25 years since its release, it’s clear what a landmark moment in Radiohead’s career OK Computer is. Laughing in the face of all who doubted its commercial appeal, the record made the band bigger than ever, claiming the number one spot in the UK album charts, earning a Grammy Award for Best Alternative Music Album, and selling almost 7 million copies globally.

In 2014, the United States National Recording Preservation Board selected the songs for a place in the National Recording Registry of the Library of Congress, a distinction reserved for music that bears a “significant cultural, historical or aesthetic impact” on American life.

Such was the impact of the record on the wider world that it inevitably inspired many lesser lights to approximate its sound, spirit, and vision, more often than not failing miserably. In reaction, Thom Yorke grew tired of guitars and got into Aphex Twin and Warp Records artists, paving the way for the about-face of Radiohead’s next album, Kid A, in 2000. That record would yet again establish a whole new blueprint and musical palette to work with. Debate about which of the Oxford five-piece’s many towering recordings stand tallest could rage on for an eternity. What’s not in question is that their third album should be in the conversation, having played a pivotal role in all that came next.

Often replicated but never matched, it was on OK Computer that Radiohead first became their very own thing. It forged a path so successful that they earned the freedom to experiment and do whatever they wanted to in the quarter century since. It remains a special release, by a band without peer. And although it was released into a world that’s virtually unrecognisable today, in many ways, what it warned against is everything that we do.