It was December 1978, and 20 degrees below freezing in Darien, Connecticut. Don Airey had left England in such a rush that he’d forgotten his coat. The keyboard player had been asked by his old friend Roger Glover to fly to the States to join Rainbow as they geared up to record their fourth album. As he walked into the rehearsal studio he passed a familiar figure on the way out

“I said to Ritchie: ‘Was that Ronnie? Is he coming back?’” Airey recalls today. “And Ritchie said something like: ‘Nah, he’s gone.’ And that was it. I don’t know what had happened, and I still don’t.”

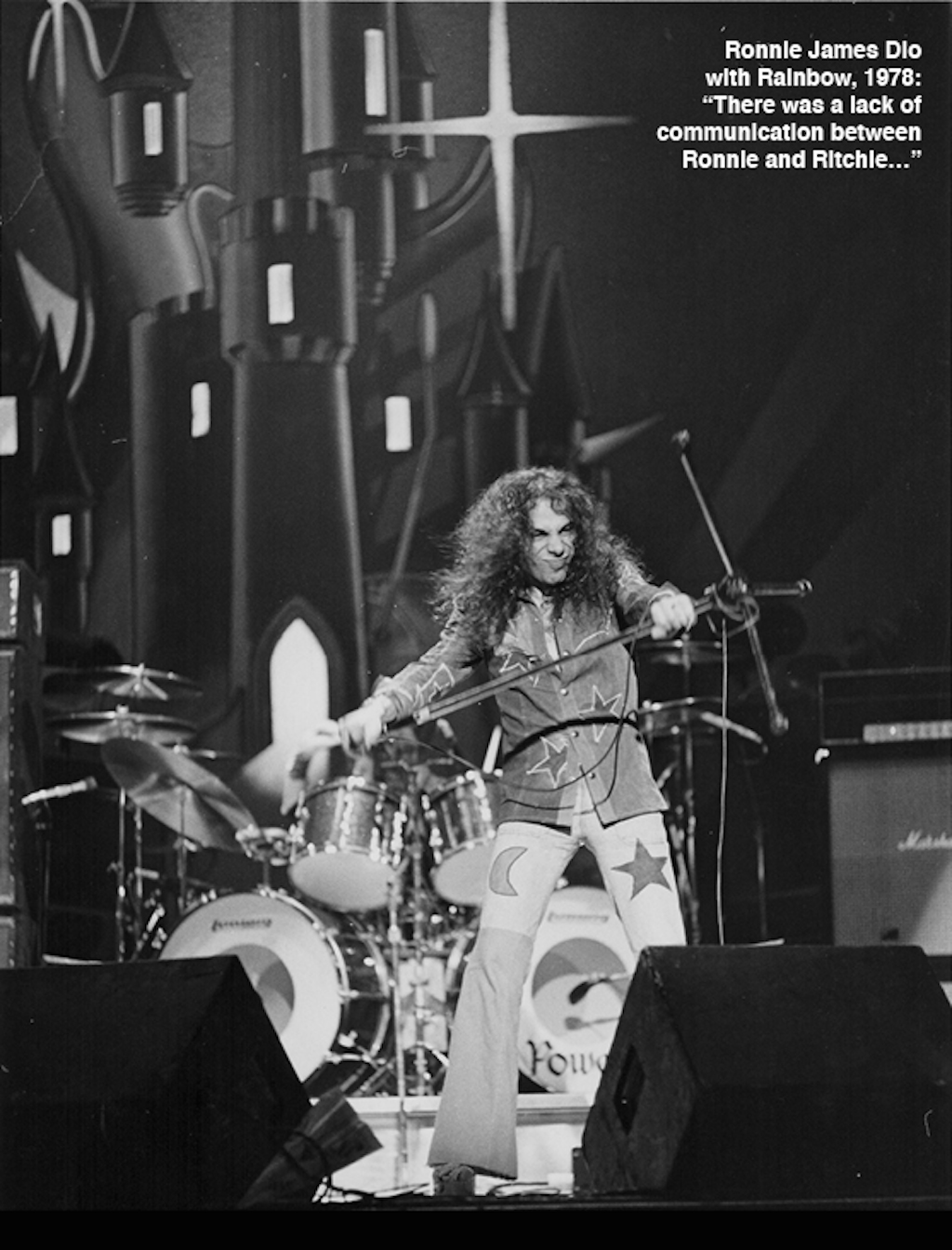

‘Ronnie’ was Ronnie James Dio, Rainbow’s leather-lunged singer since their inception three years earlier. ‘Ritchie’ was Ritchie Blackmore, the ex-Deep Purple guitarist who had founded the band and who had poached Dio from a band that had supported Purple, Elf. Over the course of three albums, the pair had forged a neo-classical sound that practically defined heavy metal during that period. But it was an increasingly uneasy partnership between these two talents. And it had just fallen apart.

Deep Purple bass player and Blackmore’s former bandmate Roger Glover had been in Connecticut for a couple of weeks longer than Airey, but the future of the band that he’d been hired to produce was unclear to him too.

“There was a lack of communication between Ronnie and Ritchie,” Glover says today of those rehearsals. “Ritchie would be working out riffs and trying out ideas for songs, and Ronnie’s in a corner writing away – he hardly ever sung a note, and when he did it was very half-hearted. I went round Ritchie’s house, and he said: ‘I’ve got an idea for a song,’ and he gave me a cassette. Then I went over to Ronnie’s house, and I’d say: ‘Ritchie wants you to listen to this.’ He’d listen to it and go: ‘Nah, I don’t like it. Here’s an idea…’ and give me another cassette for Ritchie, who’d say: ‘That’s not an idea, it’s just a rhythm…’ I woke up one morning, not long after I’d started, and our manager, Bruce Paine, said: ‘Well, it’s over. Ronnie’s left the band. Everyone’s gone except Ritchie and Cozy Powell’.”

Glover had previous with Blackmore. Five years ealier, in 1973, Deep Purple had just finished a gig in Osaka when Blackmore declared that he would be leaving the band unless Glover and Ian Gillan left instead. Hurt, Glover had poured his energies into production work, while Blackmore – who had left Purple shortly after anyway – had put together Rainbow.

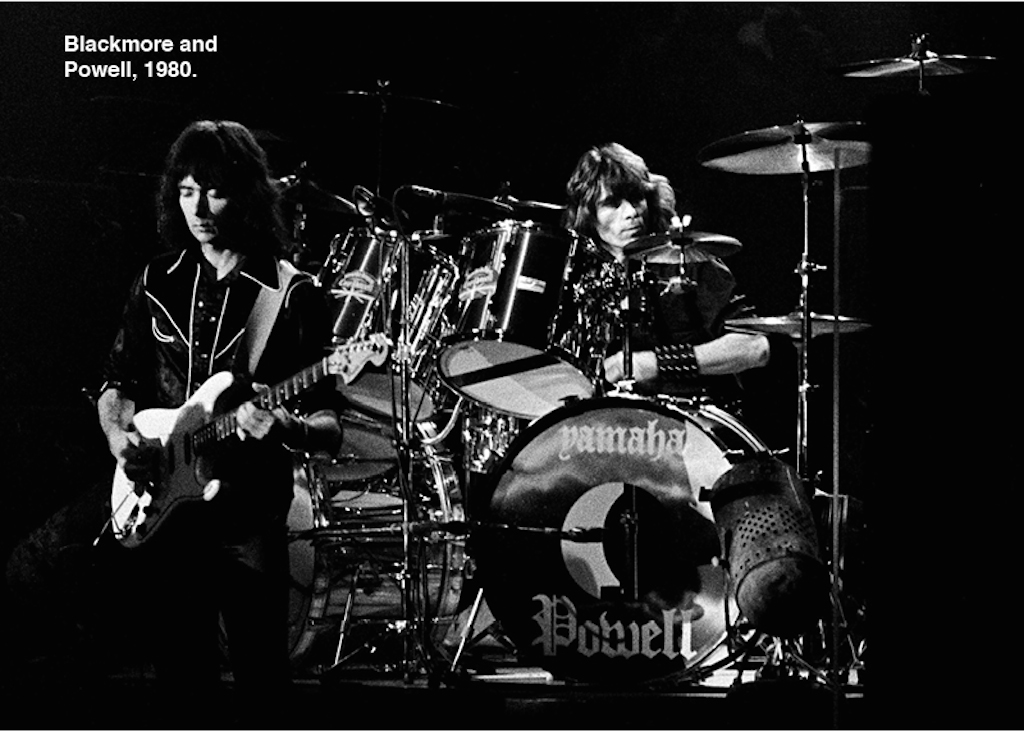

Then in July 1978 Bruce Paine – who had looked after Deep Purple back in the day – asked Glover to fly down to see Rainbow play in Chicago with a view to him producing their next record. Ritchie had been very welcoming and had agreed. But then they got to Connecticut and the wheels had come off once more. And so it was that Glover found himself in a rehearsal room in Darien, Connecticut waiting for Blackmore, Airey and Cozy Powell to come up with something that he could produce.

“Ritchie was very charming,” says Don Airey, “but he seemed to be working too hard to me. There had been a lot of grief for him. It was like he wanted a bit of peace or something. We’d start at eleven in the morning and go on until two at night, and the time just seemed to fly. You had to knuckle down for fourteen-hour days.”

Little did any of them know that when they did, it would mark a clear break with Rainbow’s epic past and set them up for the 1980s. The album this as-yet-incomplete line-up would eventually make, Down To Earth, turned them into unlikely hitmakers and resulted in the founding of one of the most iconic music festivals in history. But for the four men sitting in the rehearsal room in Connecticut that cold December, all that seemed a long way off.

Ritchie Blackmore has always been the most unknowable of rock stars. He understands the value of mystery, and he is the absence at the heart of many of the stories around him – including this one. His public statements are rare, and when they do arrive are often playful or contradictory, designed to conceal as much as they reveal. In place of anything substantive comes speculation, opinion, guesswork. Even those close to him in a professional capacity have been taken by surprise by his actions.

What we can grasp is that he is an introvert, often described as “shy”. He has obeyed his muse, however much change and upheaval that muse has demanded. He has exercised a kind of ‘soft power’, shaping the course of events as much by what he hasn’t done as what he has. He has a wicked and dry humour, and any approval he needed has come from his fans rather than fair-weather friends or payrolled entourages. As his reputation has grown, it has fed every aspect of his myth.

A psychologist might say that Blackmore has sought out conflict, consciously or not, because it drives his creativity. The list of his ex-bandmates is long, and filled with strong-minded characters. He has never been afraid to rip up everything he has established and start again. Which suggests a rock-solid belief in his ability.

That didn’t help Glover, Airey and Powell as they broke for Christmas and flew back to England. They were still unsure exactly what it was they were creating, but it already sounded more commercial than anything they’d done before. They had worked up much of the music that would become Eyes Of The World, All Night Long, Lost In Hollywood, Love’s No Friend and Makin’ Love. Elements of Eyes Of The World and Lost In Hollywood hinted at Rainbow’s grandiose past; All Night Long and Makin’ Love were direct and uncomplicated. None had the familiarity that lyrics would add, because no one was writing any lyrics, and even if they had been there was no one to sing them.

Any communication beyond the rehearsal room came indirectly: Blackmore spoke with Bruce Paine, who passed Blackmore’s instructions to Glover. It was easy to think of Blackmore as a dominant presence, yet Airey remembers a gentler dynamic.

“It didn’t run as you might think,” he says. “It wouldn’t work if someone’s a dictator, and Ritchie wasn’t like that. He was open to ideas, and pleased if you came up with something. Like all guitarists he wouldn’t listen to what you were saying, but come in the next day pretending it was his idea.”

The band travelled to Château Pelly du Cornfeld, in Southern France, near the Swiss border, to start recording. With them was Jack Green, a bassist who Ritchie thought had the right look for Rainbow. The mobile studio was too big to fit over the drawbridge of the Château, so they wedged it as close to the entrance as they could.

More pressing was the not exactly small matter of finding someone to fill Dio’s boots. They began auditioning singers, flying them to Geneva.

“Quite a few people came, some good singers,” says Don Airey. “Marc Storace [of Krokus] came. He had a wandering minstrel vibe – he had a flute with him, and I don’t think Ritchie liked that.”

But no one quite clicked, and they were burning time and money. Blackmore had a particular tone in mind, and they couldn’t find a singer who had it.

“It got to the point where we gave up flying people in and sorted it out on the phone,” says Roger Glover. “Ritchie would be there with an acoustic guitar, and I’d be holding out the phone. Ritchie would go ‘Biiing’, and they had to sing that note. Not many had the range.”

When they weren’t writing or jamming, they would sit together and throw around names of bands and singers, anyone they could think of, really. Cozy Powell had some old tapes, and music by a band from the late 60s called The Marbles came on. Blackmore looked interested. “What happened to that guy?” he asked.

The guy in question was Graham Bonnet, a 32-year-old R&B singer from Skegness who was enjoying modest success in Australia as a solo singer. Bonnet was drifting quite happily through his career without really worrying where he was headed. He was a hard-drinking, fun-loving sort, happy to leave life’s finer details to whoever happened to be managing him at the time. He had no idea how much money was in his bank account. He’d never signed a cheque or paid a tax bill. He had no interest in rock music, either.

When the call came asking Bonnet if he wanted to try out for a band called Rainbow, he thought that they were a folk group. “It sounded happy, you know? ‘Oooh, rainbows…,’” he says, laughing. He knew who Blackmore was but he’d never heard of Ronnie Dio, and it wasn’t until he went out and bought the records that he discovered what sort of music Rainbow actually made. That put him off even more. But his manager insisted that he audition, so he got on a plane.

First impressions weren’t favourable. Glover remembers the band’s shock at the shortness of Bonnet’s hair – unthinkable for a rock’n’roll band in the 1970s. And he wasn’t familiar with the song he was supposed to sing, Deep Purple’s Mistreated.

“Graham was over the other side of the room when the intro began,” Glover recalls, “and I thought: ‘He’s forgotten it already.’ Right when the vocal was about to start, he leapt across the room, grabbed the microphone and he nailed it.”

Don Airey was so shocked he stopped playing. “He started singing, and we were gobsmacked,” he remembers. “The thing ground to a halt.”

Bonnet flew back to London unsure of whether he wanted the job. They were a nice enough bunch, but they all dressed like rockers and had long hair. He preferred to keep his short and he wore 50s gear. Then there was the music: it was good, but some of it was long and he wasn’t sure where the verses and the choruses were going to come.

“It was totally alien to me,” he says. “Everybody was like semi-classical musicians. I said to my manager: ‘I don’t think I’m right for this’. My manager, thinking we could make money out of it, said: ‘No, you’ve got to do it’.”

Bonnet returned to France and joined Rainbow. He moved into the Château, which he hated. “It was bloody awful. No one wanted to do anything. The atmosphere of the place was depressing. It was creepy and there was nothing to do.”

Don Airey was sleeping in a bedroom called the Chapel, mainly because no one else would. “I thought I’d seen a ghost behind the curtain. They went in to look and there was nothing there. It turned out to have been Cozy, dressed in a hood. I still wouldn’t go back in.”

In AApril 1979, the reconstituted Rainbow left the Château and its resident spirits for Kingdom Sound studios, Long Island. There, Roger Glover took it upon himself to write some lyrics. Ritchie didn’t say anything, so he carried on. He was playing all the bass parts too, because Jack Green hadn’t worked out. Bonnet began to sing the fragments of songs that were floating around, still unsure what the band wanted from him.

“It was mainly Roger and I that had to interpret what Ritchie was aiming for, because he didn’t really give you a clue,” says Bonnet. “He just said: ‘Oh, I love your voice, man… Just have a good time.’ A lot of people think of him being dark and evil and mysterious. He really wasn’t.”

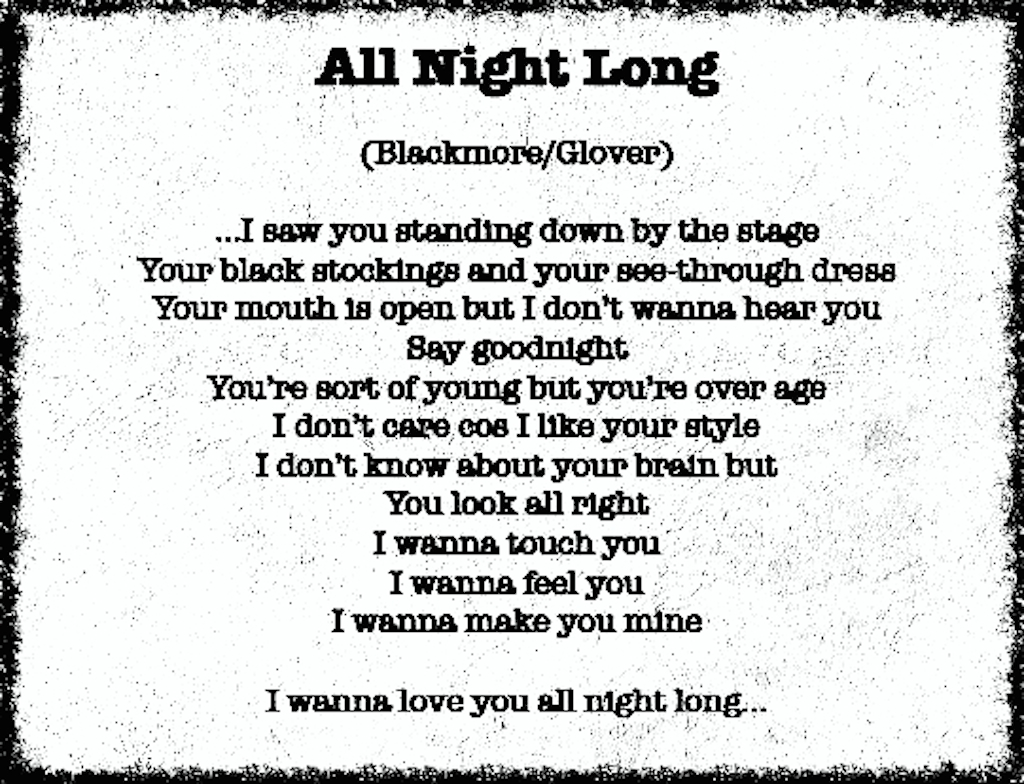

One of the first things Bonnet sang was All Night Long. Blackmore had played acoustically a riff that echoed Chris Farlowe’s Out Of Time, before Glover came in and helped steer the singer in the right direction. “In those days I was drinking very heavily. I was a total fuck-up,” Bonnet admits. “But it never seemed to get in the way of me singing. I was very lucky in that respect.”

From the chaos, a record began to form. Glover’s lyrics reached an earthy nadir with All Night Long, a song that even in the unreconstructed days of 1979 prompted a double-page spread in Sounds on sexism in rock (“Oh, it was disgusting, I admit it,” he says now. “I’m shame-faced about it.”) Glover pieced things together, leading Bonnet through the songs almost line by line.

“I didn’t want to mess up,” says Bonnet. “Roger would give me a basic idea and I’d take it a bit further. But we were constantly stopping, asking: ‘What happens here?’ A lot of the songs were made up in the studio. When I was finished I thought: ‘Well, I hope that’s good enough…’ People told me it was good, but at first I ’d have to ask.”

The key to the album was Since You Been Gone, a song written and recorded by ex-Argent guitarist Russ Ballard for his 1976 solo album Winning.

“I was at Bruce’s one night,” says Glover, “and he put this song on, Since You Been Gone. He said: ‘How about Rainbow doing it?’ I said: ‘Ritchie’s not going to play that.’ Bruce gave a sly smile and said: ‘Well, he wants to do it…’ He wanted to be on a different level and it needed to be more accessible. A shuffle towards being more successful.”

It was a classic example of the way that Blackmore allowed Bruce Paine to disseminate his ideas.

Powell, though, was implacably against the song. In France it had been a struggle to persuade the drummer to play it.

“Everyone had left except Cozy,” says Glover. “I said: ‘We’ve got to get the drum part down for this. Bruce is telling me we’ve got to do it. Ritchie wants to do it.’ He played it really badly. I said: ‘I do want it at least in time… ’ So he did another, which was incredibly basic, no passion or feel there.”

Glover eventually managed to complete Since You Been Gone despite Powell’s reluctance. “Ritchie put great guitar on it. I put hand-claps, tambourines, wobble boards… we stole the beginning idea from Kenny Loggins, that ‘Woooaaa-ohh’. And it turned out really commercial, exactly what we needed.”

It was indeed. When Down To Earth was released in July 1979 it sold 120,000 copies in

its first week in Britain alone. A month later, Since You Been Gone reached No.6 in the UK – Rainbow’s highest chart position to that point by a long chalk. Glover’s shuffle towards being successful had become a giant leap.

Rainbow had a hit album and a hit single. They also had a new bass player. Towards the end of recording, Bonnet had marched up to Blackmore and asked a question that Glover felt unable to ask himself.

“I always thought it was Don or Cozy, but Don told me a week ago it was Graham,” says Glover. “He said to Ritchie: ‘Why isn’t Roger in the band? He’s written all the stuff, he’s playing bass on it… It was Bruce that asked me. And I said: ‘Yeah.’”

Despite their success, this line-up would last just one tour, which began in the US in late 1979. Those gigs were exhausting. It was old-school gigging, five shows a week, travelling by road, staying at the low-end motels and hotels willing to accommodate rock bands – all very different to the air-conditioned luxury of the celebrity age. Bonnet had never been on tour before, and was worried about his voice holding out. Blackmore was more concerned with the length of Bonnet’s hair and his taste in shirts. By the time the band arrived in the UK in February 1980 they were big stars. Rainbow’s audience had changed: it had got younger and more female.

“We got to the first gig, at Newcastle City Hall. I drove up, parked me car, and came upon this vast wall of people who kind of stampeded me,” says Don Airey.

It was at Newcastle City Hall that Glover saw the unmistakable signs of the band beginning to pull apart. “Graham made the mistake of breaking his promise to grow his hair. It started getting quite long, down to his collar. I turned up for the soundcheck and he’d had it cut. He was almost bald. Ritchie hadn’t seen him before we got on stage. I saw him look, and just saw his face darken. He was livid, absolutely livid.”

“It was a talking point always,” says Bonnet. ‘Graham’s hair… Graham’s hair… Band meeting… What’s the band meeting about? Graham’s hair…’ It was a thing.”

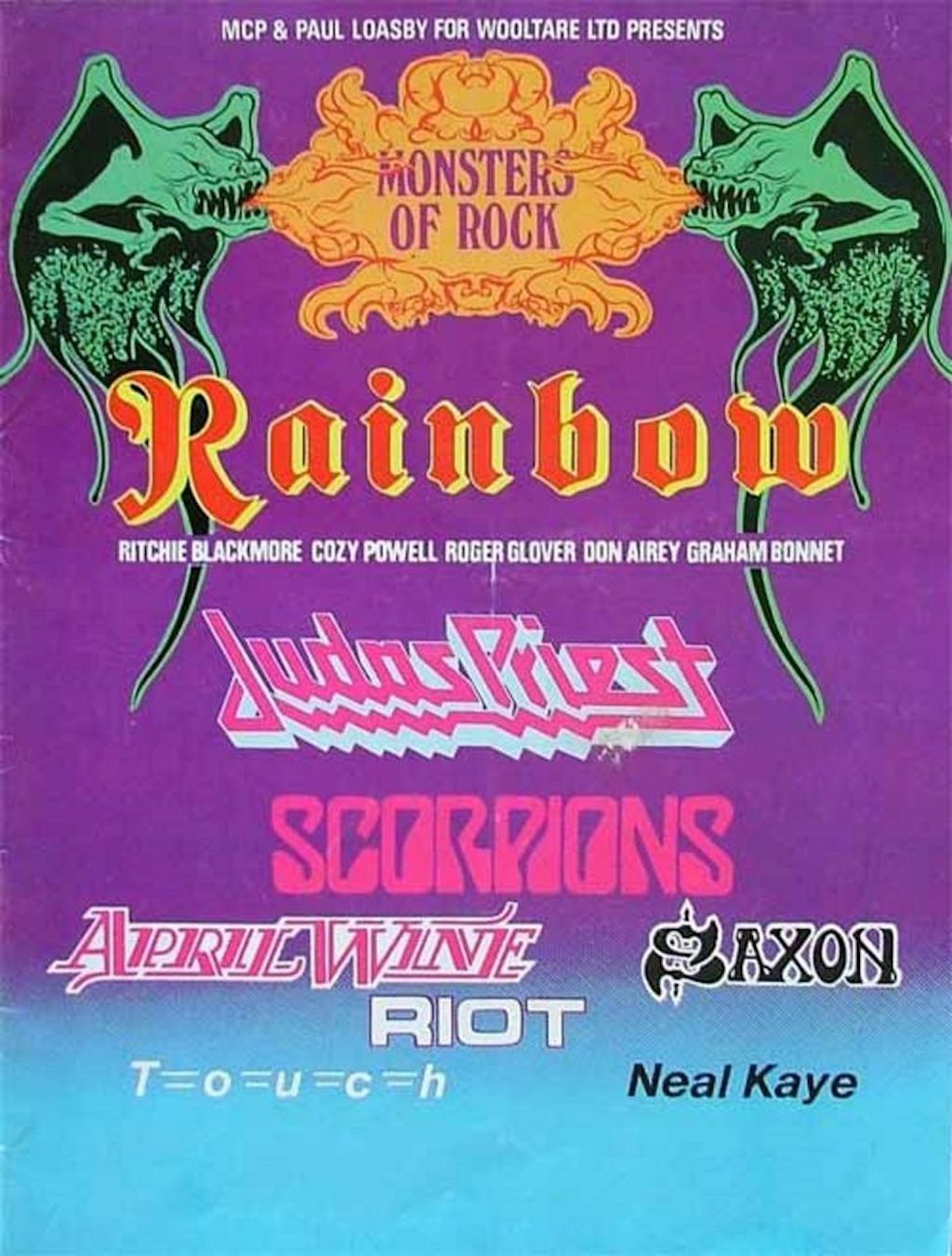

The band’s greatest day also proved to be their last. On August 16, 1980 they played at the inaugural Monsters Of Rock festival, at Donington Park racetrack. Airey recalls the idea coming from Cozy Powell, who was a motor racing enthusiast. Bruce Paine and the band’s promoter, Paul Loasby, brought in Maurice Jones, a local promoter who knew the circuit’s owners. The location was perfect – pretty much in the middle of the country – and a strong support bill had been booked, including Judas Priest and Saxon. The name was another masterstroke, beginning a franchise that would spread across Europe.

But until the day of the festival dawned, no one really knew what to expect. The official attendance was pegged at 35,000, although the actual figure has been estimated as much higher, perhaps 60,000. Admission on the gate cost £8.50.

“We’d done a bit of a soundcheck, and then Judas Priest came on,” says Airey. “They were a bit tired and unshaven, but they were incredible. Ritchie said: ‘It doesn’t do to get too complacent in this business.’ And Ritchie that day was as great as I ever heard him. Graham was amazing too. The band was cooking away.”

It was a triumphant occasion for a band whose members had experienced numerous individual triumphs of their own. But their mood was soon soured. Immediately after the show, Cozy Powell announced that he was leaving Rainbow.

“That day will forever be in my memory as one of the best days in my life,” says Graham Bonnet. “All my family were there, my friends were in the crowd. It was the most amazing day. And that day, Cozy left the frigging band… And then so did I.”

“Cozy said he was leaving. That was the big problem that day,” says Don Airey. “I don’t think he was serious. But he’d just talked himself into a corner and had to go through with it, the daft bugger. I’ve often wondered why he did it. I wish I knew. Cozy was enigmatic to his last breath.”

The others limped on to Copenhagen for rehearsals for a new album, but with only one song to work on – another Russ Ballard composition, I Surrender. Bonnet thought the band was about to fall apart, and flew home. Less than 18 months after he’d joined, Rainbow were looking for another singer.

“I really thought that it wouldn’t carry on,” he says. “Nothing was happening. There were no songs, and no one was doing anything.”

Bonnet should have known better than to second-guess Blackmore, who replaced him and Powell with Joe Lynn Turner and Bobby Rondinelli.

Rainbow went on to even greater success, before Blackmore disbanded them in 1984 in favour of a revived Deep Purple. Bonnet formed Alcatrazz. Airey quit Rainbow after the Difficult To Cure tour and joined Ozzy Osbourne. Glover remained with Rainbow until he too joined the re-formed Purple. Cozy Powell played with virtually everyone, until his death in a car accident in 1998.

Rumours of a Rainbow reunion of one sort or another persist to this day – although, perhaps fittingly, none of the Down To Earth line-up seem to know very much about it (speculation was recently fuelled by Joe Lynn Turner hinting at a post-Bonnet era reunion). Typically, Ritchie Blackmore and his plans remain as opaque as ever.

“I’ve got great admiration for him,” Don Airey concludes of the guitarist. “It’s been a long time since I’ve worked with him, and if there’s bad stuff, which there was, it tends to recede. You just look at the gold albums on the wall, and really, at bottom, he was responsible for that. He’s amazing.”

Joe Lynn Turner takes aim at Ritchie Blackmore’s Rainbow

The story of how Rainbow tried to conquer MTV, by those who were there

Listen to Ritchie Blackmore's first new Rainbow recordings in two decades