Rammstein: The birth of a legend

As a reunified Germany came to terms with its new identity, six musicians from the East Side were discovering their own. Twenty-five years on, we go back inside the birth of a legend.

Flake Lorenz can remember exactly where he was when the Berlin Wall came down. It was November 9, 1989, and his punk band, Feeling B, were playing a show in West Berlin. Nothing unusual there, except for the fact that the future Rammstein keyboard player and his bandmates were natives of East Berlin – a city that had been physically, politically and ideologically separated from its western twin for decades.

Feeling B had been allowed through the concrete barrier that split the city to play a gig as part of a government drive to show the decadent, capitalist West that the hardline socialist East wasn’t the monster on the doorstep it was frequently painted as. As the band played, Flake spotted some familiar faces in the audience – faces from East Berlin that shouldn’t have been there.

“We noticed our friends had come in,” Flake tells Metal Hammer today. “I said, ‘How can it be that they got to West Berlin? It’s not possible. Did they have to jump the Wall?’”

Someone informed him that the Wall had fallen that very night, smashed by protesters nearly 30 years after it had been erected. It was a momentous occasion, albeit one that prevented Feeling B from getting home. “It was not possible,” he says. “The holes in the wall were closed with people. It was so busy we couldn’t get back. We had to stay the night in West Berlin.”

The thing about East Germany is that it was great to grow up there, until you were 12.

Flake

On a global scale, the fall of the Berlin Wall was the most momentous event since the end of the Second World War. It sparked off the reunification of Germany and set in motion a chain of events that would end in the dismantling of the USSR and the end of the Cold War.

But for Flake and Feeling B, it had a more detrimental effect. “It changed so many things,” he says. “Nobody in East Germany wanted to listen to East German bands, because now they could listen to the real thing. Everything was possible now, where it had been forbidden in the past. And so everybody tried to make new things.”

Flake would become one of those people. Just a few years later, he and two of his Feeling B bandmates, guitarist Paul Landers and drummer Christoph Schneider, would co-found a new band whose provocative sound and warped, sardonic worldview was simultaneously linked to the nation’s divided past and symbolic of its bright, united future. Their name was Rammstein, and they would go on to become the biggest, boldest and most controversial German band of the last 25 years.

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Like Flake, Rammstein guitarist Richard Z. Kruspe grew up in what was East Germany. But where Flake says that he loved life under the socialist government – “Life was free of trouble and pressure, we all had enough money to live,” – Richard had a more complicated relationship with his native country.

“The thing about East Germany is that it was great to grow up there, until you were 12,” he told Hammer in 2014. He had moved from his hometown of Schwerin to East Berlin in his late teens. “You were presented with the illusion of a very healthy society, which worked unless you asked questions – and you don’t ask questions until you’re 12.”

Both men agree that there was a thriving underground music scene in the capital. The authoritarian East German government forced bands to apply for a licence to make music, a process that involved playing in front of a commission of eight or 10 suited people. An arty, livewire band like Feeling B could fudge the audition by changing their lyrics and toning down some of their more energetic songs. Few acts were turned down.

“There were a lot of bands, and we were all friends with each other,” remembers Flake. “We played with each other. If we needed a guitar player, we took them from another band.”

“There was new band every day,” says Richard, whose pre-Rammstein bands included Das Elegante Chaos and Orgasm Death Gimmick. “There was a scene here where everyone was making music with other people. I loved that idea. So much excitement, so much music going on.”

When the Wall finally fell in 1989, it was the beginning of a new era for all of us.

Flake

All that changed drastically after the Wall came down. While western music had previously been easily accessible on the radio (Flake: “It was the only thing that East Germany was not behind the West in”), the appetite for it suddenly exploded – and now it was readily available to gorge on.

“When the Wall finally fell in 1989, it was the beginning of a new era for all of us,” says documentary maker Carl G. Hardt, who first met Feeling B in the mid-80s (see Made In Berlin, p.45). “But we quickly realised that no one in the West was waiting for us. The structure of the East German music industry collapsed completely.

"There was hardly any demand for East German bands; western bands dominated all the opportunities to perform. The eastern bands whose music had helped bring about the collapse of the system were now forced to reposition and reinvent themselves in order to gain a foothold in this new, thoroughly commercialised music business.”

Feeling B managed to get with the programme. The band released two post-reunification albums, 1991’s Wir kriegen euch alle and 1993’s Die Maske des roten Todes, both of which Flake says were more successful than the one they released before the Wall came down.

But at the same time, Flake, Paul and Christoph had begun jamming with a trio of other East German musicians: Richard Kruspe, bassist Oliver Riedel and drummer-turned-singer Till Lindemann. And soon, this half-serious side-project would overshadow everything else.

Flake first met Till at a gig near his future bandmate’s home in East Germany. Feeling B would often ask if anyone in the audience could put them up for the night. One night, Till was in the crowd. When the shout out for five beds or even a floor came, he offered them space at his house.

“We stayed and had parties there,” says Flake. “And from time to time we came back to visit him, and so we became friends.”

Till was a former swimming prodigy turned musician. When he met Feeling B, he was playing in the Schwerin-based art-punk band First Arsch. He was soon invited along to the extra-curricular jam sessions that would eventually sow the seeds for Rammstein.

“We met without aim, without a plan, just to play for two hours,” recalls Flake. “It wasn’t a band, it was a meeting point for us, just to do something different from our real bands. It was like a therapy group.”

One of the first songs this un-named collective wrote was named after the town of Ramstein, scene of a 1988 airshow disaster in which 70 people died after two planes collided in mid-air. As word got around about this side-project, they became know as the band with the ‘Ramstein song’.

“Later people would say, ‘This is the Ramstein band’, and later it became ‘This is Ramstein,’” They soon adopted it as their name, adding an extra ‘m’. ‘Ramm’ translates into English as ‘ram’, as in ‘battering ram’, while ‘stein’ means ‘stone’. Ram-stone: a name that suited their sound perfectly.

For nearly a year and a half, Rammstein existed alongside the members’ regular bands. Sometimes they would play on the same bill as Feeling B, taking the money they earned from the latter and investing it back into their new project. Flake finds it difficult to pinpoint exactly when Rammstein became their main focus.

“It wasn’t a point, it was a feeling,” he says now. “We played a lot of shows, and we felt that the people were fascinated. And we were fascinated ourselves. We felt it could be great.”

Many of those early shows took place in small towns in the old East Germany, where Feeling B were still popular. The legendary Rammstein live show was still a few years off, however. “At the start we just went onstage in our street clothes, in our underwear,” says Flake.

There were early attempts at pyrotechnic displays, using fireworks they’d bought for New Year’s Eve parties and stockpiled. Recalls Flake: “One time we took them to the show, and thought, ‘This is great!’ And so we did a little bit more.”

It wasn’t a band, it was a meeting point for us, just to do something different from our real bands. It was like a therapy group.

Flake

East German crowds knew the members from their previous bands, and loved them. West German crowds had no idea who they were, and many early gigs in the newly accessible western half of the country were sparsely populated. “Nobody came to our shows,” says Flake bluntly of their appeal in the west.

The band’s connection with their former home country ran deeper than just crowd numbers. Till elected to sing in his native tongue from the start. This was partly down to the fact that they had all been taught Russian rather than English at school.

“I saw a lot of East German bands that sung in very bad English to people who didn’t understand English – it was absolutely stupid,” says Flake. “But if you really want to tell your emotions, you have to speak in your mother tongue. It’s not possible to tell your emotions in another language.”

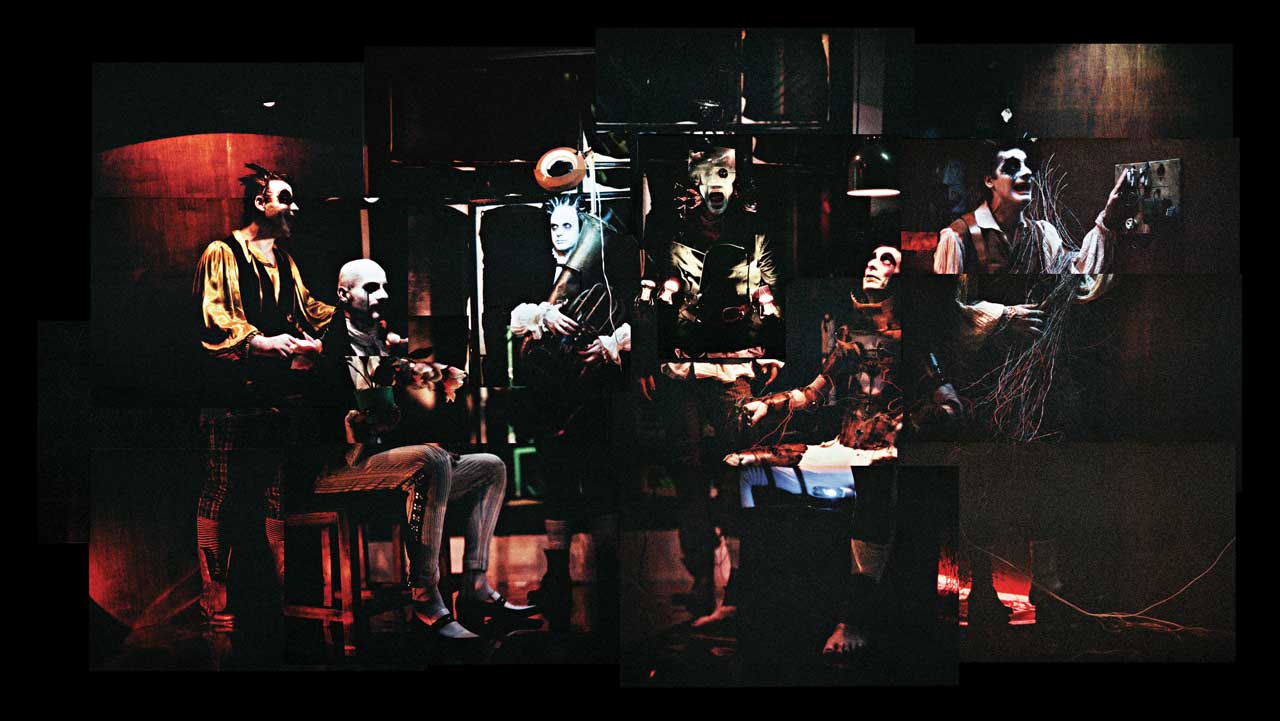

Squat culture had blossomed in post-reunification Berlin. Taking the lead of Feeling B singer Aljoscha, bands and artists would take over empty buildings and warehouses, semi-legally or illegally.

One of these buildings was a set of apartments in the city’s Prenzlauer Berg district, which became home to Aljoscha’s new political movement, Die Wydoks, as well as a film studio and a pirate radio station. It was in this building, too, that Rammstein recorded their first songs, inspired by the change in the air and the hangovers of the recent past.

Rammstein’s approach may have been radical, but their journey was surprisingly conventional. The band entered a demo tape into a competition in which the first prize was studio time. Remarkably, they won, and used their prize to record a set of demos, which in turn attracted the attention of German label Motor Music, who offered them a deal. Before they could get in the studio, there was one hurdle to overcome.

“The record company told us we had to choose a producer,” says Flake. “We didn’t know what a producer was, because we didn’t have them in East Germany. Nobody needed a producer for anything.”

The band were instructed to hit the shops and write down the names of the producers on the back of their favourite CDs. When they returned and told the label they wanted to work with Bob Rock and Rick Rubin, they were politely told to scale back their ambitions.

The man who ended up overseeing Herzeleid was Swedish producer Jacob Hellner, best known for his work with 90s rap-metal middleweights Clawfinger. He liked the demo tracks he had been sent, though it was seeing the band live that convinced him.

His only stipulation was that the band come to him to record. They reluctantly agreed, decamping to Stockholm’s Polar Studios, before moving to Jacob’s own recording space.

Things didn’t get off to the most auspicious start. The studio was cramped and it was hard for Richard to get the guitar sound he wanted. Factor in a problematic cultural gulf, and Rammstein were unhappy.

“The way Jacob worked was almost office hours,” says Richard. “So we’d be left on our own during the evenings and at weekends. We didn’t speak Swedish, or much English, and felt very alienated. We couldn’t go anywhere, nor do anything, so our mood wasn’t the best.”

Things were particularly complicated by the fact that the producer only spoke English and Swedish while the band only spoke German and Russian. The communication issues became more apparent as work progressed. The band were unhappy with how Jacob was making their music sound, a problem neither party could resolve due to linguistic barriers.

Jacob hit on a solution: he suggested bringing in an outsider who spoke both languages. The man he called in to save the album was Dutch engineer Ronald Prent.

“‘Save’ is a big word,” Ronald tells Hammer. “It wasn’t lost, but it wasn’t where they wanted it to be. We met and went through the music. I tried to get into the guys’ heads, and into Jacob Hellner’s head, to understand what they were looking for.”

At one point, somebody said, ‘You know what, maybe we should sound like Bon Jovi. Can you do that?’ And I said, ‘Sure.’ It was dead serious.

Flake

Nailing that first song was a long and sometimes fraught process. Rammstein worked as a democracy – all decisions, from where the band ate to what the songs sounded like, had to be agreed on by all six members.

“They let us do what we did,” says Ronald, who worked in tandem with Jacob, “and when we thought we had a version of it, we’d go, ‘This could be cool’ and get the band in. They would listen to it and then they would have what we later called their famous German Conference – where they went outside into a room, a living area at the studio.

They would sometimes talk for 10 minutes, sometimes for two hours, until they formed their opinion. Then they’d come back and say, ‘It sounds really great, but that’s not Rammstein – can you do something else?’”

They tried multiple mixes, altering levels, shaping guitars, raising and lowering the volume of the vocals. There were moments of comedy.

“At one point, somebody said, ‘You know what, maybe we should sound like Bon Jovi. Can you do that?’ And I said, ‘Sure.’ It was dead serious. So we mixed the track like Bon Jovi, and got really close to it. They’d come in and listen to it and say, ‘Man, that’s amazing, we really sound like Bon Jovi, but that’s not us.’”

Richard later said that the process caused tensions between the band and Ronald, but the latter has a different view of it. “Sometimes being in the studio is like a little community where you’re locked up with each other for 12 hours a day,” he says now.

“You work your ass off, and they come in and go, ‘Yeah, that’s great, but that’s not us.’ You get desperate. I might have said, ‘Maybe you want to think about this a bit more, maybe you want to give it another chance before you dismiss it’ – stuff like that.”

According to Ronald, getting the first song right took seven days. But once that was locked in, it was smoother sailing. Any friction was clearly forgotten by the time the album was done – the band asked him to come back and work on their second album, Sehnsucht.

“I created the Rammstein sound on the first two albums,” says Ronald today. “I find it difficult to say, but that’s my credit.”

Rammstein’s debut album was released in Germany on September 25, 1995. Its title, Herzeleid, roughly translated to ‘Heartbroken’ in English – a reference to the romantic problems more than one band member was going through while they were writing it.

“I was breaking up with my girlfriend and it was very tough,” recalls Richard. “I’d never experienced anything so emotionally hard before. It left me drained. Unless you’ve been through something similar, then you can’t get to grips with the way I felt.

"Till was going through something similar, and as he was a good friend I stayed with him for a few months. I suppose we helped each other out. In fact, the rest of what was to become Rammstein were also suffering personal problems of their own.”

Their collective state of mind wasn’t helped by the fact that Herzeleid was slow out of the gates. “After we released the first record, nothing happened,” says Flake. "Nobody wanted to buy it because nobody knew about it. We just played and played and played, and slowly the people in the crowd got more and more.”

Zak Tell is the singer in Clawfinger, the Swedish band whose Jacob Hellner- produced album Rammstein had liked. In late 1995 and early 1996, Clawfinger took the German band out as support on a handful of shows.

“They asked to do it. Simple as that,” Zak says today. “We were very wary of them at first. Here were a band wearing military uniforms, singing in German and rolling their ‘r’s. We were worried they could turn out to be fascist or Nazi idiots. So, we got a friend who spoke German to translate some of their lyrics, just so we could satisfy ourselves with what they were all about.”

In Rammstein, we were trying to get rid of all kind of censorship – from other people and from ourselves, too.

Richard Kruspe

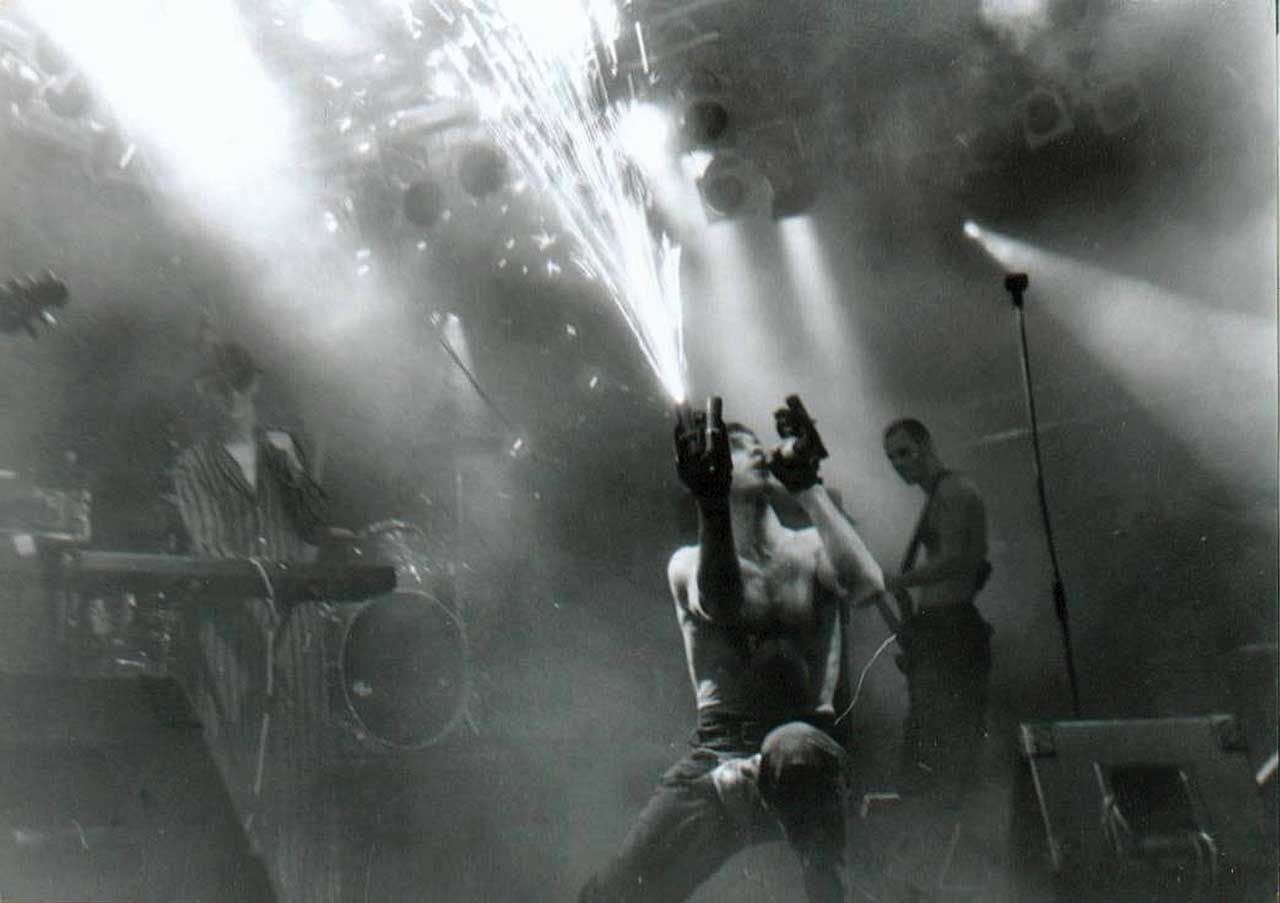

By the middle of 1996, Rammstein were headlining their own tour. The venues were small but sold out – there was the sense of an underground band starting to get a lot more attention from a wider audience. It helped that the band’s striking visual image was starting to come into focus onstage – the days of six men wearing street clothes were over. A penchant for pyros was increasingly apparent, too.

“They had a lot of fireworks and also fire on the stage,” recalls Matthias Sayer, singer with Stuttgart groove-metal band Farmer Boys, who supported Rammstein on several dates in 1996.

“Till had gloves on, which would shoot out sparks as well. I am not too certain they had official permission to do some of it back then. You had to have the right permits, and the chances are Rammstein were slightly bending the rules. But it looked very impressive. They knew what they were doing, and really did make an impression on everyone.”

Mainland Europe was starting to take notice of this strange band from the old GDR who looked and sounded like little that had come before. But their Eastern Bloc background still presented a degree of culture clash even back home in the reunited Germany.

“They were about 10 years older than us and they had also been through the whole East German system, so we found it difficult to relate to their experiences growing up – it was very different to what we’d been used to,” says Matthias. “This wasn’t a negative really, just a little odd for us. It seemed we had very little in common, even though both bands were German.”

The six members of Rammstein are the first to admit that Rammstein were a tough proposition for many people to get their heads around. But like most things relating to this deceptively enigmatic and frequently misunderstood band, there’s a method to the madness in everything they do.

“Part of the reason Rammstein were so progressive is that we felt so much censorship back in the day,” says Richard. “In Rammstein, we were trying to get rid of all kind of censorship – from other people and from ourselves, too. I think that’s why we all went, ‘What the fuck, we don’t care.’”

That single-mindedness would pay off a couple of years later when cult director David Lynch selected them to appear on the soundtrack to his 1997 arthouse movie Lost Highway. Suddenly, this insane German band with the flaming jackets and funny accents were opened up to a whole new audience. That same year their masterful second album, Sehnsucht, turned them into stars across mainland Europe, dragging the first record up by its bootlaces in the process.

“After the second record, people remembered the first,” says Flake. “We had a gold record with Sehnsucht and about five years later, the first record went gold.”

Over the next few years, Rammstein weathered a series of storms, taking in everything from onstage arrests and misguided accusations of Nazism to a wrong-headed guilt-by-association in the wake of 1999’s Columbine school massacre.

Today, they stand as one of the great success stories of the last two decades – and certainly one of the most unlikely. No one could ever have seen that coming. Especially not these six misfits from the other side of the Wall who have spent 25 years and counting bucking every trend imaginable.

“We never could be a western band,” says Flake, “because we learned in our youth that it’s important to work together and one person is not that important. And that is why we are still together.”

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.