"I went over to John's house, and he just started sobbing and said he wanted to do it": The story of the Red Hot Chili Peppers album Flea thinks is the best they ever made

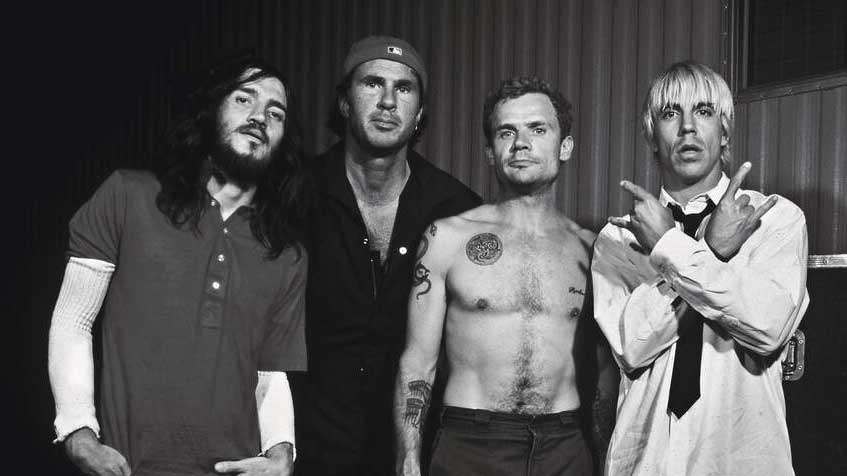

The Red Hot Chili Peppers were unravelling, but they pulled together, kept it together, and recorded their masterpiece album: Californication

"Are you more of a rock band now than funk?” I asked Anthony Kiedis as we sat having lunch by the pool at the Sunset Marquis hotel in Los Angeles. He looked at me askance. “We see ourselves as this hardcore, bone-crunching, psychedelic sex-funk band from heaven,” the Red Hot Chili Peppers frontman replied, like, ‘duh’.

It was 1990 and the Red Hot Chili Peppers had finally broken through to the mainstream with their fourth album, Mother’s Milk: their first gold album in the US; first hit single in the UK with Taste The Pain. But their audience was essentially white, rock/alternative, punk/indie fans. The Chilis had even spawned a musical progeny: funk-metal.

Indeed the 90s would soon be festooned with multiple variations of the funk-punk-metal theme, from real-deal trailblazers like Living Colour and Rage Against The Machine, to ‘thrash funk’ fusiliers like Primus, to an ocean of close-but-no-cigars like Dan Reed Network and Fishbone.

But where the Chilis boasted genuine funk cred – their second album Freaky Styley was produced by Parliament/Funkadelic legend George Clinton and featured a pair of James Brown alumni – by 1991 and their 10-million-selling album BloodSugarSexMagik, produced by Rick Rubin, and its attendant worldwide hit single Under The Bridge, their main rivals were now white stadium rock acts like Metallica and Guns N’ Roses.

I assumed this was all part of the plan, and that Kiedis was being disingenuous about his band still being more funk than rock. But as Chilis drummer Chad Smith told me years later: “After BloodSugar all our plans went out the door.” With them went 22-year-old wunderkind guitarist John Frusciante. And, not long after, very nearly the band itself

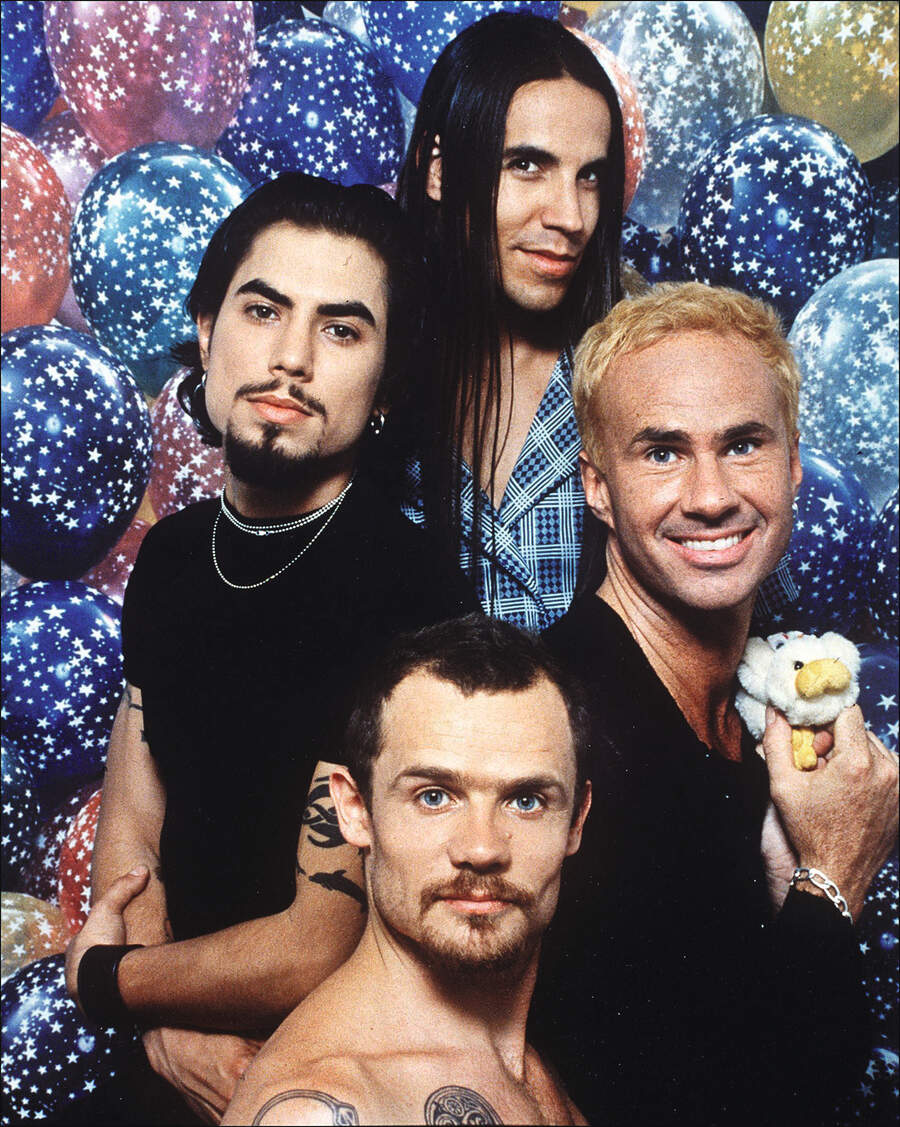

For the Red Hot Chili Peppers the rest of the 90s was essentially a washout. With Frusciante – so crucial to their success following the death-by-OD in 1988 of guitarist Hillel Slovak – now also lost to a heroin habit it would take years to recover from, the band foundered through a succession of short-lived replacements before finally settling on former Jane’s Addiction guitarist Dave Navarro.

At the time it seemed an inspired choice. Having left Jane’s with his rep sky-high, Navarro had already turned down an offer from Axl Rose to replace Izzy Stradlin in Guns N’ Roses. It was read as a slap in the face at the time – that GN’R simply weren’t cool enough for Navarro. The truth, however, was far less highfalutin, and more worrying. As he later confessed: “I was immersed in my drug addiction.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Did the Chilis know they would be replacing one junkie with another junkie when they brought him in? Or were they fooled, like the rest of us, by the too-perfect match? On the surface, 26-year-old Navarro was a prestige appointment. With his hot Latin looks and extravagant tatts, he looked as good with his shirt off as Kiedis and bassist Flea did. He was also a tremendously talented guitar player, whose main influences were Jimi Hendrix and Jimmy Page.

However, a deeper divide between the new bandmates became apparent from their very first show together, headlining the 1994 Woodstock festival. Obliged to join the others in donning a huge pantomime light bulb on his head for the opening number, Navarro was the first to jettison the get-up. Kiedis, who came up with the idea, thought it looked great, but allowed: “It was daunting for Dave. With a light bulb on your head you can’t see the frets, and if you’re in a new band you want to see what you’re playing. Plus it’s hard to look cool with a light bulb on your head.”

Then there was the light bulb now flashing in the singer’s head. Unlike Frusciante, who’d been a huge fan of the Chilis before joining, Navarro’s interest in their earlier music hovered around zero. He wasn’t funk-friendly. And pranks and leaping around having fun was an alien concept. He didn’t even like jamming. As Rick Rubin put it, Navarro was the only Chilis guitarist “who had no relation to the band’s former sound, and really came in with his own trip”.

Inevitably, in retrospect, the album they made together, One Hot Minute, released in 1995, despite again being produced by Rubin and featuring a handful of standout tracks, was a bring-down. Recorded against a backdrop of Kiedis’s own re-emerging heroin habit and Flea’s virulently anti-junkie stance following the drug-related death of his friend actor River Phoenix, Navarro’s lack of musical empathy left the process “very unfocused”, said Rubin.

One Hot Minute was another multi-platinum hit, but still sold barely a quarter what BloodSugar had. Of the five singles released from it, only one, Aeroplane, was a hit, and a minor one. By the time they returned home from tour in July 1996, they were so fractured it would be 18 months before they tried working together again. By which time Navarro’s own recurring issues with heroin had also resurfaced.

Kiedis, who had successfully been through rehab in the buildup to BloodSugar, knew what he had to do to keep the band alive. But when he and Flea, best buddies since high school, tried to talk Navarro into entering rehab, he flat-out refused – and was fired.

“Anthony says it was because I tripped and fell over an amp while on drugs,” Navarro complained. “I say that he was on more drugs than me at that point. We both had a loose relationship with reality.”

That relationship became even more tenuous after both Kiedis and Smith were involved in separate motorcycle crashes. An exhausted and spooked Flea took off for Costa Rica, where he spent his time reading a biography of Che Guevara and laying around in a hammock near the beach.

A frustrated Smith (“You can’t sit around playing drums on your own like you can a guitar”) actually hooked up with Navarro and Marilyn Manson bassist Twiggy Ramiro in a new band they called Spread, and a 17-track demo was made for a planned album tentatively titled Unicorns & Rainbows: The Pelican.

For Kiedis there were no quick-fire solutions. Instead he spent the next six months travelling around Australia, New Zealand, Thailand, “to get my mind, body and spirit working together in preparation for something I didn’t even know was going to happen”. Following the hippie trail to India, he swam in the River Ganges to try to cure his ills. He visited the Dalai Lama in his Dharamsala monastery. One story has him undergoing an Eastern drug detox. Until he discovered that “what I was looking for was in my own backyard”.

Which was?

“My friends.”

Late summer ’98. With Kiedis back in LA, Flea made one last desperate attempt to keep the band together by going to Frusciante and trying to persuade him to re-join. Ironically, the guitarist had just come out of rehab. More than five years of serious smack addiction had left the 28-year-old a complete wreck: rotting teeth, ruined veins, his body ravaged by cigarette burns and self-inflicted scars.

“I would try to hint to him and Anthony about accepting the other one, and both of them were like: ‘Nooo.’ But when John was in the hospital, Anthony visited him and they started becoming friends again.” He added: “I went over to John’s house, and he just started sobbing and said he wanted to do it.”

In the interim, Flea had begun writing material for a solo album, “all sensitive guitar and me singing”. That plan was hurriedly revised when Frusciante and Kiedis appeared on his doorstep one day. The fact that Frusciante was holding a guitar was symbolic. He’d pawned all his guitars to buy heroin.

“It was such an incredible sight,” said Flea. “I thought: “Fuck the solo record, it’s time to do this.”

They began small, no big announcements, just jamming in Flea’s garage.

“I became just giddy with joy, really, hearing that combination of musicians playing together,” Kiedis recalled. “It was kind of miraculous."

Once they were all finally in the same room again together, things immediately started to fall into place. With Navarro out of the picture, Flea had originally suggested they record an electronica album somewhere between U2’s Zooropa and The Prodigy’s The Fat Of The Land. That idea was jettisoned after both William Orbit (fresh from creating Madonna’s Ray Of Light, the biggest album of 1998) and David Bowie turned down the job of producer. Working as a four-piece again, out of Daniel Lanois’s El Teatro studio, they began to revert to musical type: alt.rock with punk-funk influences.

Frusciante, though, was deep into the gloom-minimalism of Joy Division, Fugazi and The Cure. Kiedis was revisiting childhood trauma on a major scale. The young smartass who wrote Party On Your Pussy was now 36, back living alone after the break-up of his long-term relationship to 23-year-old New York fashion designer Yohanna Logan.

Combined with Frusciante’s rich new otherworldly guitar playing, and the fresh injection of dramatic energy it inspired in Flea and Smith, Kiedis was finally putting his truth into poetry. Like the extraordinary Scar Tissue. What would eventually be the first single from the album, Scar Tissue is so beautiful, so musically and lyrically refined, it shimmers. The same forlorn guitar as Under the Bridge, but seven years and a million miles further on. As Kiedis recites his brittle verses: ‘Soft spoken with a broken jaw, step outside but not to brawl/And autumn’s sweet, we call it fall, I’ll make it to the Moon if I have to crawl…’

On This Velvet Glove, the heartbroken singer addresses Yohana tenderly as the band provide a lush rippling backdrop: ‘Your solar eyes are like nothing I have ever seen, somebody close that can see right through/I’d take a fall and you know that I’d do anything I will for you…’

Around 35 new numbers were sketched out this way, including the bones of a Frusciante instrumental inspired by Carnage Visors, a doomy 27-minute instrumental by The Cure for the 1981 soundtrack to an obscure animated short film of the same name. After Flea and Smith had built it into a musical cathedral, and Kiedis spilled his blood verses, it became a modern musical odyssey titled Californication. Nevertheless, it was only at Kiedis’s insistence that the track wasn’t scrapped, and Frusciante found his final riff only two days before recording it.

What’s different is the commentary, the street polemic, the focus on the big picture, all the way down the dirty boulevard. The band reaching for suitably hellred crescendos at each increasingly tortured turn: ‘Space may be the final frontier, but it’s made in a Hollywood basement/And Cobain, can you hear the spheres singing songs off Station To Station?/And Alderaan’s not far away, it’s Californication…’

Kiedis was later quoted as saying the point behind Californication was to “tell tales of wandering souls who’ve lost their way searching for the American dream in California”. But that sounded like a made-up quote from a press release.

Most of the material was inspired by unmistakably autobiographical events: Porcelain came from Kiedis meeting a young single mother at the YMCA who was fighting addiction while trying to raise an infant daughter. He recalled: “The mum’s in a haze, strung-out on heroin, but the little girl’s this beaming wide sun-ball of an angel. The juxtaposition of their energies [was] profound.” The juddering melancholic Emit Remmus, with its references to Leicester Square and Primrose Hill, was inspired by Kiedis’s short-lived relationship with Melanic C of the Spice Girls.

Similarly, Frusciante felt free at last to fully express his split musical personality. On Get On Top, his starting point is the ultra-funk zap of Public Enemy, while that knotty, angular guitar solo was formed from listening intently to Steve Howe’s undulating solo on Siberian Khatru from the classic 1972 Yes album Close To The Edge. His room-full-of-mirrors guitar effects on Saviour – Kiedis’s heartfelt tribute to higher power – were “directly inspired by Eric Clapton’s playing in Cream”.

The psychedelic-sex-funk was still in evidence on Around The World, Get On Top, I Like Dirt, Purple Stain and Right On Time. The other 10 tracks on Californication leant far more towards the melodic. Tracks like Scar Tissue and the equally moody Otherside were less about jamming and more about structure.

Recording time was booked at Cello studio on Sunset Boulevard, and for eight weeks from January 1999 the three Harley-Davidsons belonging to Flea, Kiedis and Smith were lined up by the back door. All four members played their instruments and recorded together in real time.

Rick Rubin returned to oversee production, and was surprised to find the band on time each day, unfailingly professional, and, shock-horror, sober. Gone were the “day-long pot sessions or sexual indulgences” that had slowed work on previous albums. The Red Hot Chili Peppers now moved fast, and had all the basic tracks laid down in five days.

Not everything went smoothly, however. The new drug-free détente tested badly when the band vetoed a Kiedis favourite, Fat Dance, off the album. “It talked about the beauty of ass,” Kiedis shrugged. It would be several years before anyone got to hear it.

Meanwhile, the low-riding groove of Easily was a track that Rubin and Frusciante had to fight to get on the album. Which was a bizarre situation, given how immediately catchy the tune is. A number like album closer Road Trippin’ reignited that good feeling, though. It’s a song of summer featuring Beatles-esque acoustic guitars and lush pop orchestration, about how surfing with your best friends is better than any drug.

Released in June 1999, Californication was an instant, globe-straddling success, going straight into the US chart at No.3 and hitting the UK top five. In the US it eventually stayed glued to the Billboard chart for 101 weeks and was certified seven-times platinum. In the UK it stuck around even longer, staying on the chart for 169 weeks, and was eventually certified four-times platinum for more than 1.2 million sales.

And while UK music weekly NME sneered: “Can we have our brain-dead, half-dressed funkhop rock animals back now, please?” almost everybody else bent the knee for the album Flea considered to be “the best record the Chili Peppers have ever made”. Rolling Stone described it as “epiphanic”. Even the eminent Village Voice critic Robert Christgau got on the good foot, characterising the band as “New Age fuck fiends” and citing Scar Tissue and Purple Stain as personal highlights.

“Because we were starting afresh, it was like being back at album number one again,” said Kiedis. As such, Californication lifted the Red Hot Chili Peppers out of the blinkered cultural ghetto One Hot Minute had left them in, and elevated their status to that of eventual inductees into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame, where they duly landed in 2012.

Indeed the long-term influence of Californication went way beyond the music. It’s a late-90s masterpiece that served as a better segue into what the 21st century was going to be all about than any other record of its era, whether funk, metal, rap, rock, or sock.

“The art of the Red Hot Chili Peppers is first and foremost that of our music, and we never change our music as a compromise for anybody’s desires or tastes,” Kiedis had insisted during our long-ago lunch in LA. “This is showbusiness, and we are here to entertain. We like to entertain people. But there’s a lot more to it than that. People who are truly interested or concerned will find that out eventually.”

We certainly did that.

Mick Wall is the UK's best-known rock writer, author and TV and radio programme maker, and is the author of numerous critically-acclaimed books, including definitive, bestselling titles on Led Zeppelin (When Giants Walked the Earth), Metallica (Enter Night), AC/DC (Hell Ain't a Bad Place To Be), Black Sabbath (Symptom of the Universe), Lou Reed, The Doors (Love Becomes a Funeral Pyre), Guns N' Roses and Lemmy. He lives in England.

![Red Hot Chili Peppers - Aeroplane [Official Music Video] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/vV8IAOojoAA/maxresdefault.jpg)

![Red Hot Chili Peppers - Scar Tissue [Official Music Video] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/mzJj5-lubeM/maxresdefault.jpg)

![Red Hot Chili Peppers - Californication (Official Music Video) [HD UPGRADE] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/YlUKcNNmywk/maxresdefault.jpg)

![Red Hot Chili Peppers - Otherside [Official Music Video] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/rn_YodiJO6k/maxresdefault.jpg)

![Red Hot Chili Peppers - Around The World [Official Music Video] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/a9eNQZbjpJk/maxresdefault.jpg)