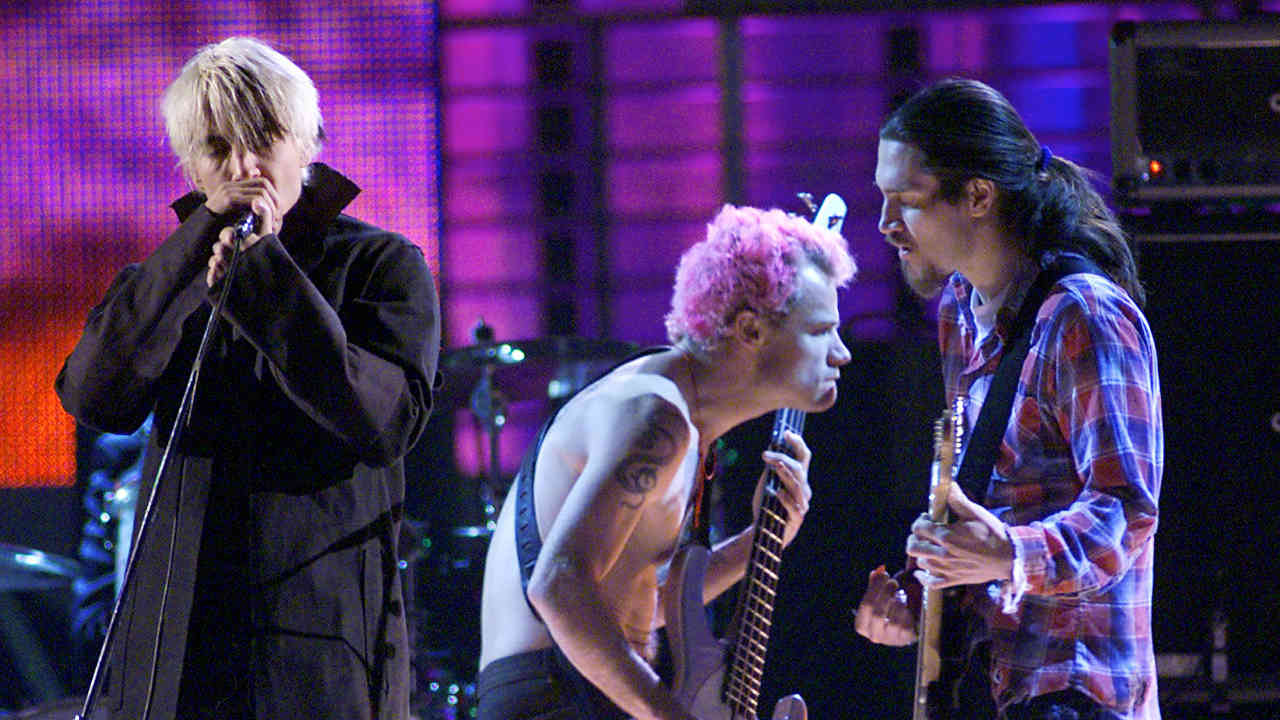

On June 14, 1998, the prodigal son came home. When the Red Hot Chili Peppers walked out onstage at the Tibetan Freedom Concert at Washington DC’s RFK Stadium, it was with guitarist John Frusciante, the man who had deserted them mid-tour six years earlier and spent the ensuing period in a full-blown drug hell.

It was Frusciante’s highest-profile appearance since reconnecting with his estranged bandmates earlier that year. But this was more than a reunion: it signified the return of man who had journeyed to the brink of death.

It nearly didn’t happen. Storms caused the show to run over and the Chili Peppers, who were last minute additions to the bill, looked like they wouldn’t be able to play. But headliners Pearl Jam – who had supported the Chilis in their very early days – threatened to pull out unless organisers cut their set short by 15 minutes so their old friends could take the stage.

The band played just three songs that night: Give It Away, Under The Bridge and The Power Of Equality. But the truncated setlist didn’t matter. What mattered was that the band and Frusciante had emerged from a decade of drama intact. The Red Hot Chili Peppers were whole again.

John Frusciante was 18 years old when he played his first gig with the Chili Peppers, in November 1988. His new bandmates were barely a decade older but it felt like they’d lived many more lives than he had.

Singer Anthony Kiedis and bassist Flea had formed the Red Hot Chili Peppers with guitarist Hillel Slovak and drummer Jack Irons in 1983. They were the ultimate good-time party band, the exuberance of their songs mirrored by the chaos of their lifestyle. Kiedis and Slovak especially were ardent drug users, with heroin their favoured means of getting wasted. But the good times screeched to a halt in June 1988, when Slovak died of an overdose at the age of 26.

Frusciante was the natural replacement. He had discovered the Chili Peppers when he was 15 and was a regular at their LA club gigs. He already knew their songs inside out, and aced his audition. “I realized that I wanted to be a rock star, do drugs and get girls,” Frusciante told Guitar Player.

He joined a band who were still grieving - and in Kiedis’ case, still wrestling with his demons. Despite his own hedonistic ambitions, the teenage Frusciante barely even smoked pot, prompting his new bandmates to nickname him “Greenie”.

The Chilis’ first album with Frusciante, 1989’s Mother’s Milk, was their most successful yet, selling 500,000 copies in the US. But it was 1991’s Rick Rubin-produced Blood Sugar Sex Magik, that turned them into superstars. It was a measure of their success that both Nirvana and Pearl Jam opened for them in late 1991.

Yet as the record sales rose and the shows got bigger, Frusciante found himself struggling with the scale of the band’s fame. The omens were there even before he’d joined the band. Hillel Slovak once asked the younger man if he thought the Chili Peppers would still be popular if they played the 17,000-capacity LA Forum. No, Frusciante had replied, it would ruin the whole thing.

Now the guitarist was watching his prophecy come true. “John would say, ‘We’re too popular, I don’t need to be at this level of success, I would just be proud to be playing this music in clubs like you guys were doing two years ago,’” wrote Kiedis in his book, Scar Tissue, adding that the pair would get into to heated arguments backstage.

The relationship between the alpha male singer and the sensitive guitarist had broken down. “Of all personal understandings in the band, the one between Anthony and I was the worst,” Frusciante told Dutch magazine Oor. “Our relationship had reached an all-time low before Blood Sugar Sex Magik.”

Frusciante’s fragile state of mind wasn’t helped by his chemical intake. The kid whose bandmates had nicknamed him “Greenie” due to his lack of experience with drugs had reportedly shot heroin for the first time shortly after finishing Blood Sugar Sex Magik, and now his dabblings were getting serious - something that both concerned and angered Anthony Kiedis, who was trying to maintain his own sobriety.

The toxic combination of drugs, fracturing interpersonal relationships and the pressure of being in a hugely successful band was impacting on Frusciante’s mental health. The snapping point came in the summer of 1992. As the band flew to Japan for a series of shows, the guitarist started to hear voices in his head: “You won’t make it during the tour, you have to go now.”

That’s precisely what he did. On May 7, 1992, just after playing a show in the city of Saitama, John Frusciante walked out on the Red Hot Chili Peppers mid-tour, flew back to America and disappeared into a black hole of his own creation.

Between the summer of 1992 and his eventual return to the Red Hot Chili Peppers six years later, John Frusciante hovered between life and death. Following the aborted Japanese tour, he figured his life as a professional musician was over. The fog of depression prompted a freefall into full-blown addiction: heroin, cocaine, crack, anything he could get his hands on.

The role of drug addict with a death wish was one Frusciante embraced. He holed up in a house in the Hollywood Hills, walling himself off from his former life. His waking hours were divided between snorting, smoking or shooting up and dazed artistic endeavours – painting, writing short stories, making lo-fi four-track recordings.

As Frusciante’s addictions worsened, his friends began to drift away, their concern at his well-being giving way to helpless fatalism: no one thought he was going to make it out alive. One of the people who had stayed close was River Phoenix. The My Own Private Idaho star moved in with Frusciante in October 1993, and the two of them would spend days at a time getting high and not sleeping. Frusciante was reportedly with the actor on the night he collapsed and died of a drug overdose on the pavement outside LA club The Viper Room on October 31, 1993.

In 1994, Frusciante released his debut solo album, Niandra Lades And Usually Just A T-Shirt. Its skeletal, half-there song-sketches were a world away from the Chili Peppers’ taut funk-rock gymnastics and a reflection of the guitarist’s precarious physical and mental state. It sold just 15,000 copies. But then that was exactly what John Frusciante wanted.

As the 1990s progressed, his life got even darker. His arms became covered with scars, the result of abscesses from shooting heroin and cocaine, and he began to lose his teeth. At one point, he nearly died from a blood infection. He tried half-heartedly to get clean, but it never stuck. In a 1996 piece on the guitarist for the LA New Times, journalist Robert Wilonsky described him as “a skeleton covered in thin skin.”

“[Heroin] helps you do anything better you want to do,” Frusciante told Wilonsky. “At least for me, not for other people. A lot of people… they know that when I’m clean I lose the sparkle in my eye, I lose my personality, I’m not happy, I’m kinda empty.”

Frusciante seemed to exist in a vortex of darkness. In 1996, his house in the Hollywood Hills burnt down, destroying several guitars and tapes of the music he was working on. He moved into the Chateau Marmont, the hotel where comedian John Belushi died of a speedball overdose nearly 25 years before. When he was kicked out of there, he moved to another hotel, and then onto another.

His shifting residential situation didn’t stop Frusciante from releasing a second solo album, 1997’s Smile From The Streets You Hold, a record that was even more untethered to reality than its predecessor. Frusciante later claimed that he made the album for “drug money”, and it sounds like it. This was the work of someone who had lost interest in the world and in themselves.

“I had no image to care about or present to anyone,” he told Alt Press. “I wasn’t ashamed… I was as close to dying as a person could be.”

Frusciante’s sudden departure had left a hole that his former bandmates struggled to fill. The first guitarist they recruited, Arik Marshall, lasted less than a year. The second, Jesse Tobias, barely notched up a month. “We were looking for very specific, cosmic characteristics, and they weren’t presenting themselves,” Kiedis told Rolling Stone.

A seemingly permanent solution was under their noses. Dave Navarro was the guitarist with Jane’s Addiction, a band whose rise to fame paralleled the Chili Peppers’ own, right down to their drugs habits. Jane’s fell apart at the end of 1991, and the Chilis saw Navarro as the perfect replacement for Frusciante. He rebuffed their first request, but the band persevered and he said yes at the second time of asking.

The union didn’t quite deliver on its promise. Their sole album together, 1995’s One Hot Minute, was solid rather than spectacular. Navarro’s psychedelic heavy rock style wasn’t a great fit for the Chili Peppers’ groove-centred approach. It didn’t help that both Navarro and Kiedis were falling back into bad old ways. “We both had a loose grip on reality,” the guitarist later admitted.

Whether the reasons were musical or chemical, the partnership between the Chilis and their latest guitarist officially dissolved in 1998. “We did not fire him; he did not quit,” Flea told Alternative Press the following year. “It was like, this is not working.’ Basically, the intangible things that make magic happen were not happening.”

And so the Red Hot Chili Peppers found themselves without a guitarist for the second time in six years. But bringing the magic back this time would prove to be a lot easier.

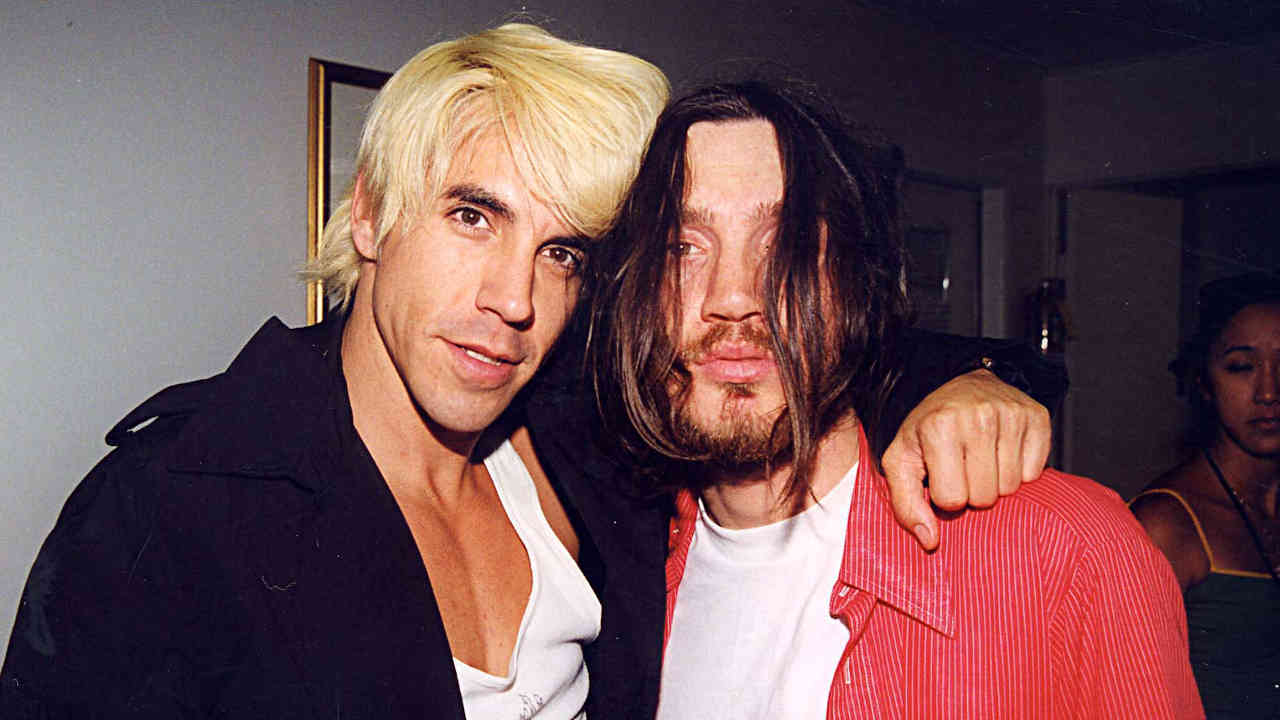

When John Frusciante and Anthony Kiedis met at a gig by the reunited Jane’s Addiction near the end of 1997, it was the first time they had spoken in five years. Flea had stayed sporadically in touch with Frusciante, but Kiedis, angered by the guitarist’s mid-tour departure in Japan, had not.

“He wasn’t on drugs, but I was and he wasn’t judgemental,” Frusciante told Rock Sound of their encounter. “He used to give you a bad vibe about pot and drinking, but he was just cool.”

It was Flea who suggested they call Frusciante after Navarro’s departure. The guitarist had begun hearing voices again, except this time they told him he would die if he didn’t quit drugs. Frusciante listened to them, checking himself into rehab that January to clean up and save himself.

Kiedis was sceptical about getting his former bandmate back, but Flea dug in. The bassist told him that he would quit the band if they didn’t at least call Frusciante.

“When Dave left, Flea called me up and asked me what I thought about playing with John,” the singer told Kerrang!. “I told him it would be a dream, but that it was a very far-fetched concept. Then a week later we were playing together.”

Things moved fast. With three months of a “bombastic” - Kiedis’ words – rehearsal, the Red Hot Chili Peppers were onstage at the Tibetan Freedom Concert in Washington DC with Frusciante. Soon, they were working on songs for their first album with the guitarist since Blood Sugar Sex Magik.

The original plan was to make an electronica album. “I feel the most exciting music happening is electronica, without a doubt,” said Flea. They considered Brian Eno, William Orbit, U2 associate Flood and even David Bowie as producers, none of whom were available.

Instead, they went back to Rick Rubin, who had produced Blood Sugar… and One Hot Minute. Rubin allayed any doubts as to Frusciante’s physical and mental wellbeing. “He’s brimming with ideas, and he lives and breathes music more than anyone I’ve ever seen in my life,” the producer told Spin of the guitarist, who would go spend tens of thousands of dollars on surgery to clear up the scars on his arms and replace his ruined teeth.

Frusciante’s renewed vigour reinvigorated the Chili Peppers. Their seventh album, Californication, felt less like the work of a band picking up where they’d left off almost a decade earlier, and more like the start of an entirely new chapter. It didn’t ditch the funk rock of the past so much as hone it into something mature and intelligent. Around The World and Parallel Universe ramped up the energy, but the slower songs – Scar Tissue, Otherside and the title track, with its acute dissection of the California state of mind – showed a more thoughtful, measured side to the band. But Flea batted away suggestions that it signified the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ rebirth.

“I just feel that we always exist,” the bassist told Rock Sound. “John, Chad, Anthony and me. It’s like we’re still around, we always have been.”

“Not me,” added Frusciante. “Everybody thought I was dead. But as you can see, I’m very much alive.”

Californication was released on June 8, 1999. It reached No.3 in the US, and would go on to sell more than 15 million copies worldwide - more, even, than Blood Sugar Sex Magik.

But the album’s real triumph wasn’t its commercial success. Kiedis acknowledged that Californication effectively saved the Chili Peppers (“Until John rejoined, Flea was at the end of his Chili Peppers rope,” said the singer). More importantly, as Frusciante acknowledged, it signified his own return from a journey that was almost destined to end in tragedy.

“It’s a second chance for all of us,” he told NYRock. “In a way, we’re all co-dependent and we know it, but we also trust each other.”

The momentum from Californication carried the Chili Peppers and Frusciante through 2002’s By Your Side and on to 2006’s sprawling and under-rated Stadium Arcadium. Yet there was always a sense that old ghosts – if not demons – could return, and the guitarist bailed on the band for a second time in 2009 to pursue his solo career. Frusciante even recommended his own understudy, Josh Klinghoffer, as his replacement.

Yet even that wasn’t the end of the story. In 2019, Frusciante returned to the band, displacing Klinghoffer. “It’s just returning to family,” he said in 2021. “I’m extremely comfortable with those people. It was as if no time at all had gone by.”