Released in 1987, R.E.M.’s Document was a watershed album, not only for the band but also for so-called ‘alternative rock’. Blame later incarnations of the band for subsequent offences committed by Coldplay and Keane, if you must, but if you do you also have to acknowledge the part REM played in shaping the likes of Nirvana and Radiohead.

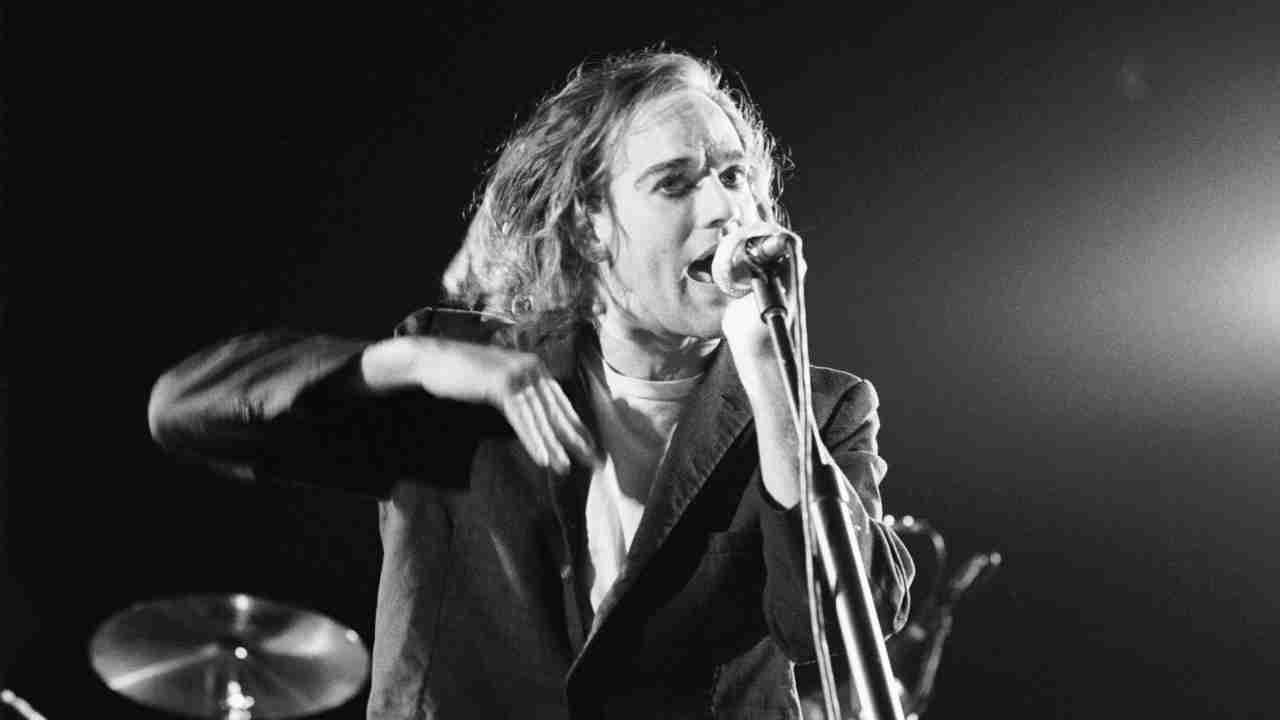

Over the first few years of their recording life, R.E.M. developed an instantly recognisable, highly idiosyncratic musical style based on, in guitarist Peter Buck’s words, “this weird, post-folk, long melody line type-thing”. Drummer Bill Berry booted it along, Mike Mills supplied melodic, propulsive bass, and both added sugar-coated backing vocals, while Buck wrung a post-Byrdsian jangle from his Rickenbacker guitar, and Michael Stipe made up nonsense lyrics, and murmured them while clinging to the mic for dear life.

Fast forward to late 1985, and R.E.M.’s sales had increased steadily, but not dramatically. The band were college radio and fanzine faves in the US, and music press darlings in the UK – which wasn’t enough to sustain a career. “We’d been on the road for five-and-a-half years, and it was kind of tense,” is how Buck summed it up. “Everyone was tired of being away from home, and broke, and always in each other’s company. It reached a point where we were totally ambivalent about going on.”

The band’s record company, IRS, was owned by Miles ‘brother of Stuart’ Copeland. Miles had aligned himself to punk from the start, but – like all music business entrepreneurs – he was keen to make the most of any potential for success. R.E.M. were his best shot – if only they stopped insisting on putting atmosphere so high on their list of priorities, and not including hit singles at all.

For 1986’s Lifes Rich Pageant [it doesn’t have an apostrophe], the band agreed to work with producer Don Gehman, who’d enjoyed recent success with John Mellencamp’s immediate brand of blue-collar rock. It was an uncomfortable combination, but the resulting – and, in retrospect, clearly transitional – album stands up surprisingly well. What really soured it for R.E.M. – and marked the beginning of the end of their relationship with their record label – was when IRS’s distributor MCA told them they wouldn’t be getting behind Pageant because they still couldn’t hear a hit single.

Scared by the lack of material they’d had to work with last time around, R.E.M. had started writing Document even before the release of Pageant. The musicians set up in their Athens, Georgia rehearsal studio and jammed noise until they got interesting fragments they could work on later, dubbing this the ‘chaos method’. According to Buck, it produced “this real discordant Gang Of Four-meets-Wire-meets Sonic Youth stuff” – no doubt influenced by the cover of Wire’s Strange R.E.M. played on 1986’s Pageantry tour.

“Anything crunchy or angular was in, and anything jangly or comfortable was out,” was how Buck summed it up. When it came time to record, he and the band were keen to give these new songs “a really big sound with lots of chaotic stuff on top. Full of weirdness, backwards stuff and noise.” Scott Litt, who had worked with R.E.M. faves The dBs, and had recently produced an unabashed summer pop hit for Katrina & The Waves with Walking On Sunshine, took over production. He agreed with R.E.M.’s goals, in part: “I like having a big sound. I like having bold sounds.” But he also had his own priorities. “I like having a singer that grabs you. I wouldn’t accept anything less.” And his primary brief from IRS was to deliver that elusive hit.

The extent to which R.E.M. were happy to compromise, or were manipulated into conforming, is still open to debate. Mindful of their hard-won image as incorruptible artistes, the band have always made it sound as though all the changes they underwent were of their own choice and making. But it’s strange that after so many years resisting the dictates of 80s production they suddenly seemed so willing to embrace them. This time, R.E.M. would spend an unprecedented seven weeks in the studio: more preparation, more takes of basic tracks, far more overdubs, and much longer spent mixing.

After a bad experience early in the band’s career, Bill Berry had always refused to play to click tracks, but now agreed it was a good idea to use them to maintain an appropriately mechanical beat for about half of the songs. He also agreed to have his drums retuned before each track was recorded, something which had not previously been a priority. “We didn’t set out to mix the vocals louder; it just seemed natural,” claimed Mike Mills. Stipe declared that, while he had previously been mistrustful of studio technology, he had now suddenly overcome his fear. “I decided I would have to try to explore it and use it as a tool rather than be used by it. I finally got the kind of sound, the kind of urgency that I wanted.”

R.E.M. used a Fairlight sampler to add found noises to the chaos on many of Document’s tracks, but decided to erase a lot of the wilder stuff at the mixing stage. Meaning it was mostly left to Peter Buck to bring the noise. Previously, he’d been low-key about his guitar playing on record, but “this time I got a bit greedy” with chunky power chords, distorted rhythm riffs and even distorted lead. Opening cut Finest Worksong introduces Buck’s new chainsaw whine, periodically rising to an insistent screech.

Stipe’s voice and words are almost as in-yer-face. Only just out of his shell, and already the tortoise was a hare. Especially on the urgent, part-improvised torrent of words that makes It’s The End Of The World As We Know It (And I Feel Fine) such a euphoric headrush. By way of extreme contrast, The One I Love is spare, brooding and direct. “It’s very clear that it’s about using people over and over again,” said Stipe. “It’s not an attractive quality.”

Although those are perhaps the album’s two best known songs, they don’t dictate its lyrical mood. The opening sequence of tracks reflects the political situation at the time the album was written – ‘greed is good’ yuppiedom and disregard for the disenfranchised in Finest Worksong; US imperialism and ecological short-sightedness in Welcome To The Occupation; music business witch-hunts and media smearing of opposition politicians in Exhuming McCarthy. The chaos method of composition had clearly influenced the lyrical content: this is a world gone mad. Stipe subsequently stated that the whole album is about chaos and fire. “All you have to do is turn on the TV and you’re inundated by complete lies from people who are supposed to be running this country,” said Buck.

Ultimately, though, Document doesn’t owe its impact to any one style of writing, or tempo, or to any one element in the mix. Rhythms klutz or throb, guitars niggle or yaw, basses decompress or boom, and words circle or cascade. Even the self-imposed ‘out with the old R.E.M., in with the new’ dictate isn’t that firmly adhered to: King Of Birds and Oddfellows Local 151 are character narratives worthy of 1985’s Fables Of The Reconstruction, while Buck concedes that Disturbance At The Heron House is effectively a slowed down remake of much earlier R.E.M. song Gardening At Night.

Some think that R.E.M. forsook their earlier mystery and warmth on Document. But the lyrics are still oblique, and they don’t give up the whole story on first listen. And how appropriate is it to be cosy, anyway, when the world’s falling down around your ears? Great art says something about the human condition in the time of its making. And great rock’n’roll has a long-standing tradition of bringing the news to all the young dudes.

Scott Litt won his bet that The One I Love would be R.E.M.’s breakthrough hit single: it snuck under the radar as a straightforward love song in the US, and made it to No.9. Rolling Stone recognised the band’s time had come, putting them on its cover with the line, ‘America’s Best Rock’n’Roll Band.’ Document went on to become R.E.M.’s first million-selling album. A combination of all the above enabled the band to negotiate a massive new deal with WEA, including a cast-iron artistic freedom clause. That, combined with their ongoing refinements of the chaos method, set the band up for a decade-long run of multimillion-selling leviathans: from Green via the patchy Out Of Time to the awesome Automatic For The People, then past the frankly not-that-great Monster to the shamefully underrated New Adventures In Hi-Fi.

Yes, there were too many ‘big, dumb pop song’ singles, and yes, there is no (and never was any) excuse for Shiny Happy People. And yes, after Berry quit and Scott Litt was dropped, the magic went, too. But for a good few years there, R.E.M. were indeed America’s – and the world’s – best thinking man’s rock’n’roll band. Document is the document of their move into the big time.

Originally published in Classic Rock 107. May 2007