Metal, not grunge. This is the thought I woke up with this morning, a few days after Chris Cornell’s sad and unexpected death in Detroit.

Metal, not grunge.

When I travelled to Seattle at the start of 1989 to cover a whole slew of unkempt, unruly, long-haired bands releasing records – coloured vinyl and the odd 12-inch – on local label Sub Pop, Soundgarden were already a breed apart. The band were signed to three labels – SST, Sub Pop and major label A&M – and had been making considerable inroads into the music industry. I met them as a matter of course alongside their more brattish peers – Nirvana, Mudhoney, the man-behemoth Tad, and so forth – and already, it seemed, there was confusion over what the actual sound of Seattle was.

Soundgarden had not formed overnight (the band started in 1984), and they played unrequited metal – albeit metal melded with deranged humour on their debut 1988 album Ultramega OK. And even then, with the psychedelic metal pulse of their early albums, and the mighty agitation of Hands All Over from 1989’s turbulent, genre-reinventing Louder Than Love, they seemed more serious somehow, more focused.

Blues, not punk.

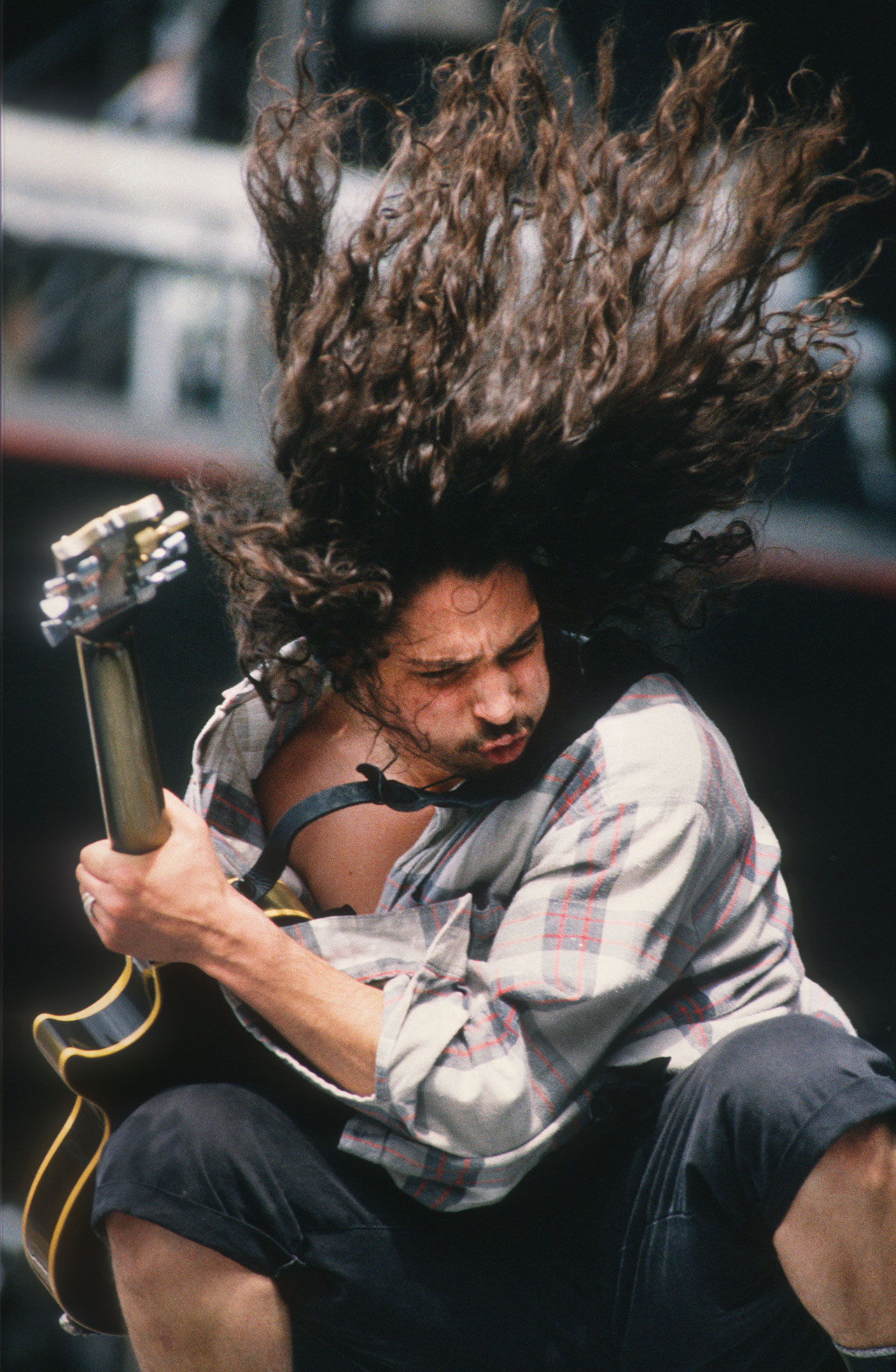

Maybe it was Chris Cornell’s voice – otherworldly and near-feminine in its higher register, a force of nature, a freakstorm not heard since the early days of metal in the 1970s. Maybe it was Kim Thayil’s guitar, churning and breaking and sprawling everywhere… or Matt Cameron’s drumming (it’s far easier to ruin a band with a bad drummer than with any other instrument)… or the thunderous bass of Hiro Yamamoto (later to be replaced by Jason Everman, and him by Ben Shepherd).

Certainly the band already cast a long shadow over the nascent Seattle scene – grunge or no grunge. Their music, their cool, no-fucking-dickheads attitude to gender issues and day-to-day living, their mountainous power… all of these were major influences on the newer bands. The band’s early slogan, Total Fucking Godhead, was no empty promise. Nirvana, in particular, went through a period of wanting to be Soundgarden Mk.II – they shared two bassists (Everman and Shepherd, a former Nirvana roadie) and a producer (Jack Endino), and their debut album, Bleach, was in places Soundgarden lite.

Soundgarden were inexorably entwined with Sub Pop’s early years: it was on Kim Thayil’s advice that his buddy Jonathan Poneman contacted Olympia fanzine writer Bruce Pavitt with the idea of forming the label. Drummer Matt Cameron came from Endino’s band Skin Yard.

I cannot recall when I first met Soundgarden – possibly it was in the Sub Pop offices on the tenth floor of the Terminal Sales Building on 1st, with the framed Matt Groening cartoon on Bruce Pavitt’s office wall, or maybe it was in the first Starbucks down in Pike Place Market, where half the Sub Pop roster worked. Everyone hung around with everyone else back then.

Undeniably, however, Cornell had the makings of a star. It wasn’t just the way he’d rip his shirt off at a moment’s notice, revealing rippling biceps. He possessed a stardust that I have only ever spotted in one other star: Björk. Some of Soundgarden’s contemporaries were bothered by the notion of rock stardom, of taking the Jesus Christ pose. This notion never bothered Cornell. There was something about the way he carried himself, his casual brilliance. It wasn’t that he was stand-offish. Far from it. Just that he quite clearly was going to shine. (I never made the same observation about Cobain or any of his peers, and even now sometimes find myself surprised at how famous that particular relocated Seattle resident became.)

There was a near-legendary Soundgarden show in London, possibly their first, a double headliner with Mudhoney (supported by forgotten hardcore band Murphy’s Law), where the makeshift stage collapsed and a whole bunch of us had to form a human chain, dragging the trestle tables backstage and hurling them into an empty room before anyone got crushed. After the chaos, Soundgarden ended their set with Cornell announcing: “We’re Black Sabbath. Good night.”

The band, meanwhile, had become taken with my willingness to plant myself firmly in the action, grappling drunkenly up on stage to hurl insults down the microphone at the audience, and ‘sing’ a few improvised songs. When I caught up with the group a few months later (earlier? Everything was so confused back then), in the Dutch squat/venue the Vera Groningen, Cornell dragged me up on stage to duet with him on a truncated version of Some Enchanted Evening (from the Hollywood musical South Pacific), before the band roadie rugby tackled me into the wings. The set that night in Holland, 1989, was incendiary.

To this Chelmsford boy who had grown up reading the UK music press at the time of post-punk and had been trained to believe that all metal (with the honourable exception of Motörhead) was both wrong and evil, it was more than about loving great music. It was a revelation, an awakening – for the first time, I understood the attraction of metal. It is fun to thrash your hair from side to side, to churn a groove into the floor, to scream heedless into the dark night. The fact that Soundgarden were so clearly cool people – willing to laugh, not willing to take bullshit in whatever form it came – was a considerable fucking bonus. Definitely a bonus, and probably an important factor in my burgeoning love for this genre.

When it came to the interview I did for Melody Maker, Soundgarden, like their colleagues and friends on Sub Pop, understood one inveterate rule: rock’n’roll has never been about truth. Rock’n’roll is not about the facts. Rock’n’roll has always been about furthering the mythology, inventing your own backstory, creating your own path. Rock’n’roll is where we hide. First exhibit, the interview…

Soundgarden first met at a teen hop in Seattle. Chris Cornell, vocals and bare torso, takes up the story from the depths of a youth hostel bedroom in Groningen: “We were playing in a band called The Shemps, dressed in tuxedos,” he recalls. “We threw our guitars down in disgust and quit, because we weren’t expressing ourselves as we wanted to. So we formed a three-piece band where I played drums and sang, and Hiro [bass] sang backups and Kim played guitar and did the doo-wops.

“We started writing jangly, creepy-crawly songs, giving them names like Blood and Open Sesame and Bury My Head In The Sand. We supported Hüsker Dü as a three-piece, blew them away and got into a wrestling match with them afterwards. The drummer sat on us and spilt Rice Krispies in Kim’s beard. All we wanted was the crowd to cheer and carry us around on their shoulders.”

Ultramega OK was nominated for a Grammy in 1990 – as was its breakthrough follow-up, 1991’s Badmotorfinger. Grunge did not break Soundgarden, Soundgarden helped to break grunge. Soundgarden wanted to embrace the mainstream. Their sound and look was everywhere in Seattle in those early turbulent years. And, crucially for all that sprawled out of the Pacific Northwest during the start of the 1990s, Soundgarden were positive role models.

Their music may have followed the template of the early Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin screamers, but it still managed to be inventive and mess with the form. Often, it felt the music had more in common with the manic experimentation of (now forgotten) SST labelmates Das Damen and the hard, psychedelic rock of Cream than with any of the ‘poodle rockers’ that back then were everywhere on the metal scene. In the same way that Nirvana helped revitalise alternative rock with punk attitude and feminist leanings, Soundgarden gave metal a much-needed overhaul and kicking, bringing it back to the raw power of its origins. It rekindled the thrust of its engines. All of a sudden, rock music rocked once more. Jesus Christ Pose is nu metal a decade ahead of schedule (back then it was termed ‘grindcore’), and weirdly sounds right in place with the music of its time (Big Black, the God Machine). Not that Soundgarden appreciated being lumped in with Poison or Bon Jovi.

“When we released Louder Than Love,” Cornell told me in a Tokyo hotel room in March 1994, “everyone wanted us to be heavy metal because that’s what was big – the record company, the publicists, the heavy metal magazines especially, who were having a pretty serious time trying to find something worthy to write about because all the bands sound exactly the fucking same, sing about the same shit and have nothing to say. It’s a totally lacking genre.

“Part of that categorisation was our fault, because Louder Than Love was a metal record and, being our debut for a major, was the one that made the impression. Badmotorfinger led away from there, but probably not enough. To us it never made any sense, because we knew where we came from and the songs we would write.”

It’s ironic that Chris was talking that way, then. Superunknown – Soundgarden’s 1994 album that blew everyone away, and the reason I was talking to him in Japan – is unadulterated, unrequited, unapologetic metal. Pure and beautiful. Listen to The Day I Tried To Live, with its heart-clenching vocal performance, and try telling me that it’s not an equal of Sabbath or Zep. Listen to the era-defining Black Hole Sun (era-defining, at the time of Cobain’s death) and try convincing anyone that this is not metal shot through and through.

The primal blues, moved on through distortion and time.

Understandable, though, that Cornell and Thayil wanted to distance themselves from the crap, the shit that just gets passed over too many times. Back then, only Metallica could equal Soundgarden for emotional range, and they fell away fast. (Metallica themselves acknowledge Soundgarden’s status – guitarist Kirk Hammett told Rolling Stone magazine in 2008 that Enter Sandman might never have existed if it hadn’t been for the “big, heavy riffs” on Louder Than Love.)

In retrospect, perhaps it should have been obvious that the final days of Soundgarden were to shortly be upon us. Only one album followed before the band’s inevitable re-formation in 2010, 1996’s wonderfully bleak Down On The Upside. As Cameron termed Superunknown to me in ’94, “It grooves and it rocks and everything is where it should be. I can listen to it. Normally, rock songs are about certain things – chicks, cars and dicks. But the lyrics to Superunknown are very introspective, very dark. They’re saying a whole different thing. Basically it’s a big ‘fuck you’ to the world, a plea to leave us alone!”

Perhaps it should have been obvious, but it wasn’t – the band were still too busy rocking, and arguing, and fighting, and… up to mischief. In Nagoya, in front of a wildly enthusiastic club audience, Cornell stopped the band’s set halfway through to announce a “real special guest star, all the way from England”. The audience went suitably berserk, expecting Lemmy or someone. Instead they got me.

I want to leave the final word to Chris Cornell, from the same 1994 interview, something he said that always stuck with me. Fellow songwriter Ben Shepherd was the most visibly depressed, guitarist Kim Thayil the most argumentative, but it was Cornell who bothered me the most. Always.

“Fell On Black Days was like this ongoing fear I’ve had for years,” he said. “It’s a feeling that everyone gets. You’re happy with your life, everything’s going well, things are exciting, when all of a sudden you realise you’re unhappy in the extreme, to the point of being really, really scared. There’s no particular event you can pin the feeling down to, it’s just that you realise one day that everything in your life is fucked!”

He shouts the last word.

RIP Chris Cornell and Soundgarden. You totally fucking rocked.

Music world pays tribute to Chris Cornell

Chris Cornell’s widow Vicky writes open letter to late singer