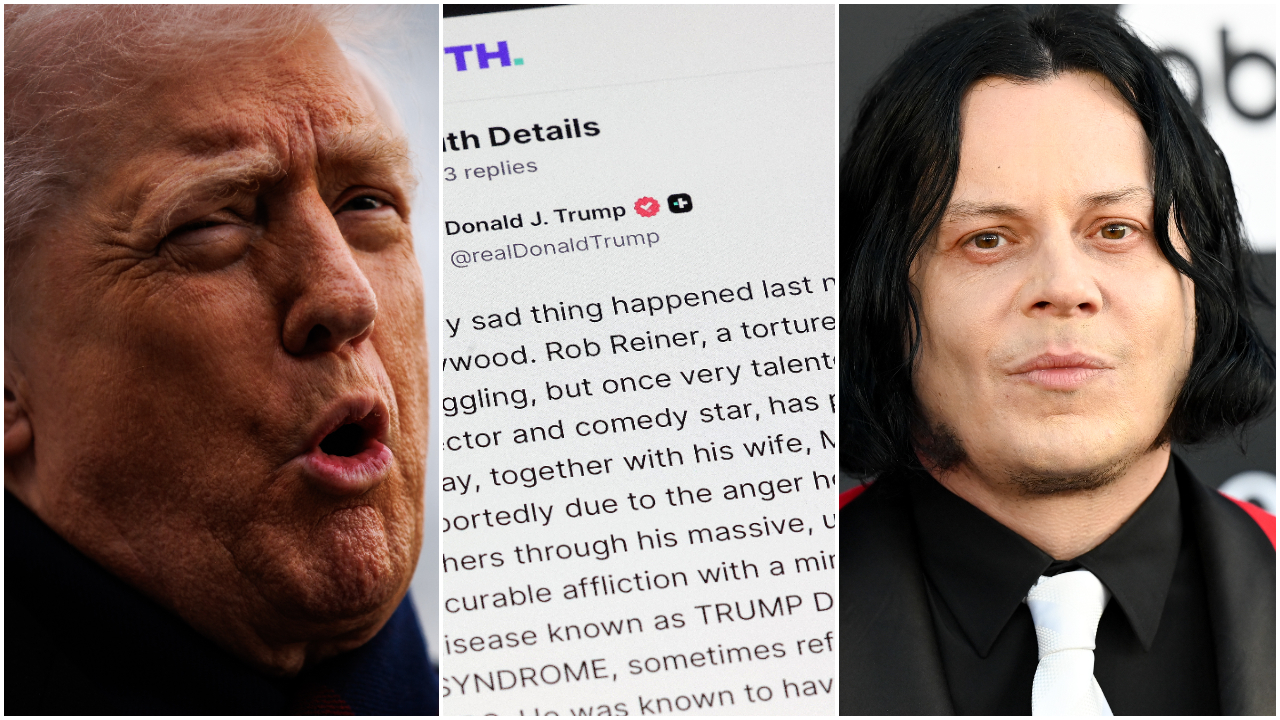

Remembering Chris Cornell: The latter years

By 1998, Soundgarden had split up and Chris Cornell was turning his attention to other projects. Through it all, he would experience his highest and lowest points

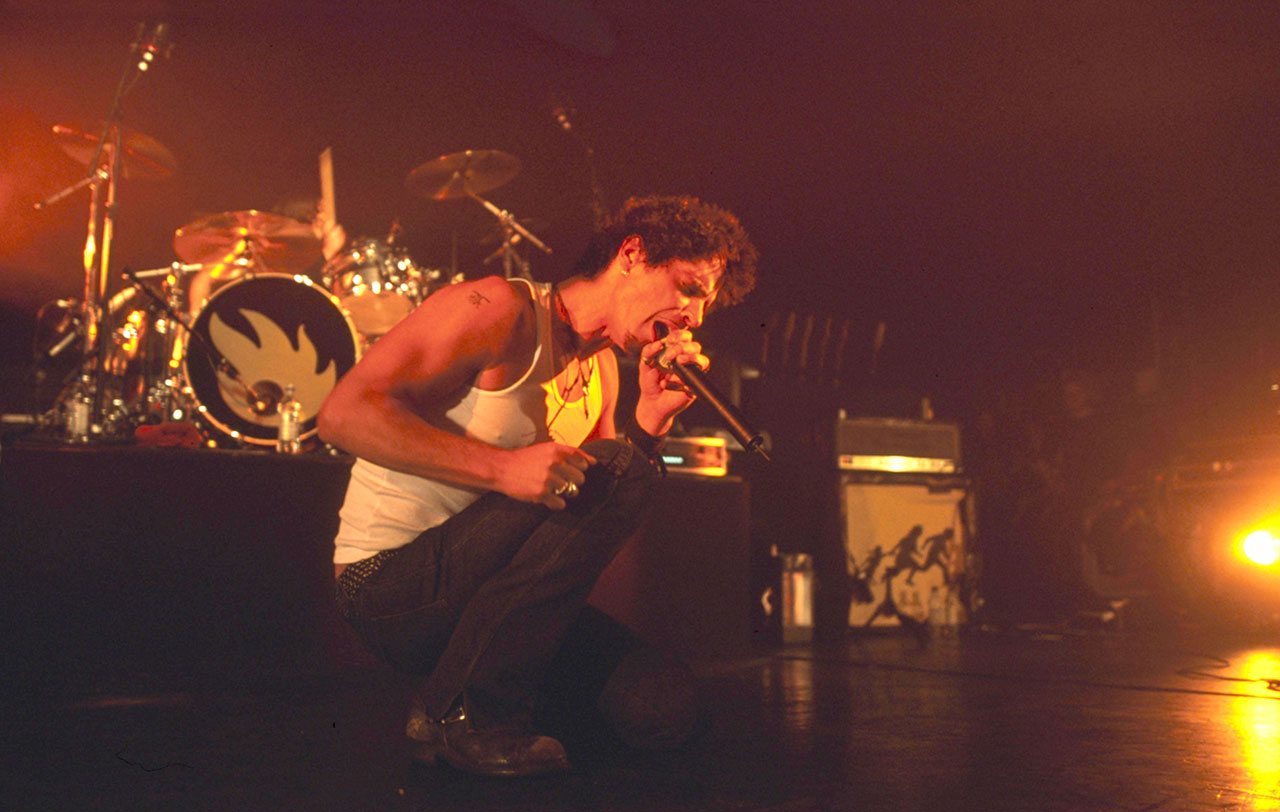

When on April 10, 1997, Soundgarden formally announced they were disbanding, it marked the end of one of the most unlikely success stories of a decade full of them.

As with most things in Chris Cornell’s life, the end of Soundgarden when it came was low-key and understated. There were rumours of internal tensions and dissatisfaction with their touring schedule, but as far as these things go, it ended with a sigh rather than an explosion. “We weren’t a band who ended up strangling each other or fighting with lawyers,” Cornell said later.

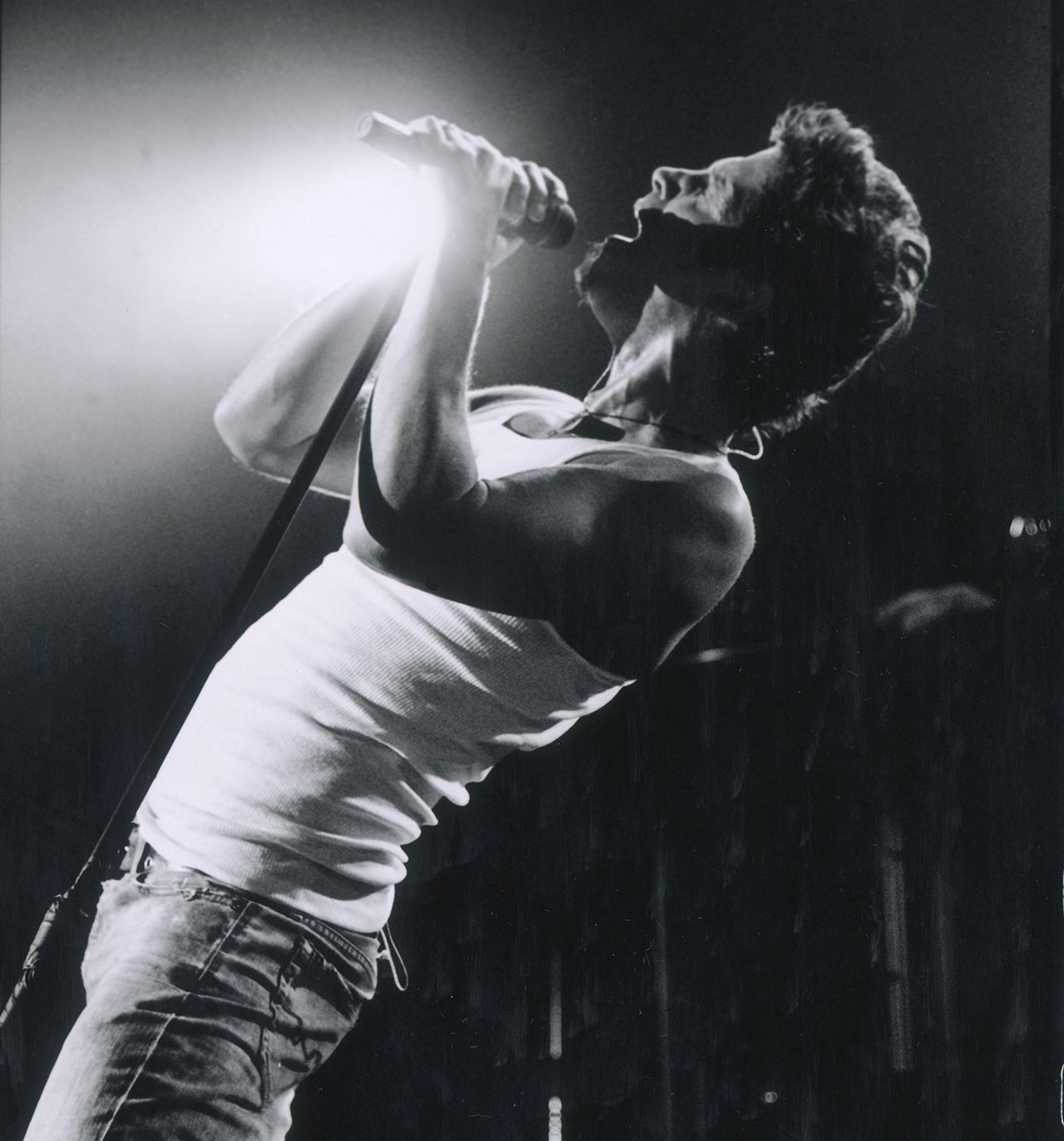

Free from the confines of Soundgarden, the singer was free to embark on a new chapter – one that would see him scale all the highs and plunge to all the lows life has to offer. If Act I of Chris Cornell’s life was a steady rise to the top, then in retrospect, Act II was one long battle to keep the darkness at bay – a battle he would ultimately lose.

Cornell wasn’t new to the idea of being a solo musician. He’d had an acoustic track, Seasons, on the soundtrack of the 1992 grunge rom-com Singles, and he even recorded a set of songs for that film’s fictional band, Citizen Dick. But he later admitted that the idea of going it alone filled him with trepidation.

“I went through a serious crisis with depression where I didn’t eat a whole meal every day,” he told Seattle P-I in 2006. “I was just kind of shutting down. I eventually found that the only way out of that was to change virtually everything in my life. That was a very frightening thing to do, but it was worthwhile.”

This angst had been hidden in plain sight throughout his time with Soundgarden, but now he was about to lay it all out on the table with his debut solo album, Euphoria Morning. Released in September 1999, it found Cornell abandoning Soundgarden’s twisted take on arena rock in favour of a more measured, confessional singer-songwriter approach that owed more to the melancholy side of Temple Of The Dog.

Beneath the luxurious production, songs such as Can’t Change Me, Preaching The End Of The World and Wave Goodbye (the latter a tribute to the singer Jeff Buckley, a friend of Cornell’s who had drowned in 1997) were shot through with bleakness. The fact that he originally wanted to call the album Euphoria Mourning, with its suggestion of desperate mood swings, hinted at his state of mind.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Euphoria Morning sold decently, though nowhere near the number his old band had racked up. But Cornell had more to worry about. His marriage to former Soundgarden manager Susan Silver was crumbling. To deal with it he found solace in drink – and other substances.

“That was the beginning of a very, very rough period,” he said. “Eventually I went from someone who drank occasionally to someone who was pretty much daily an alcoholic, and then taking other drugs, because I was sick from being an alcoholic. And then having problems with those prescription medications. And then a mental deterioration occurred. A huge depression. I had trouble doing anything, or wanting to do anything.”

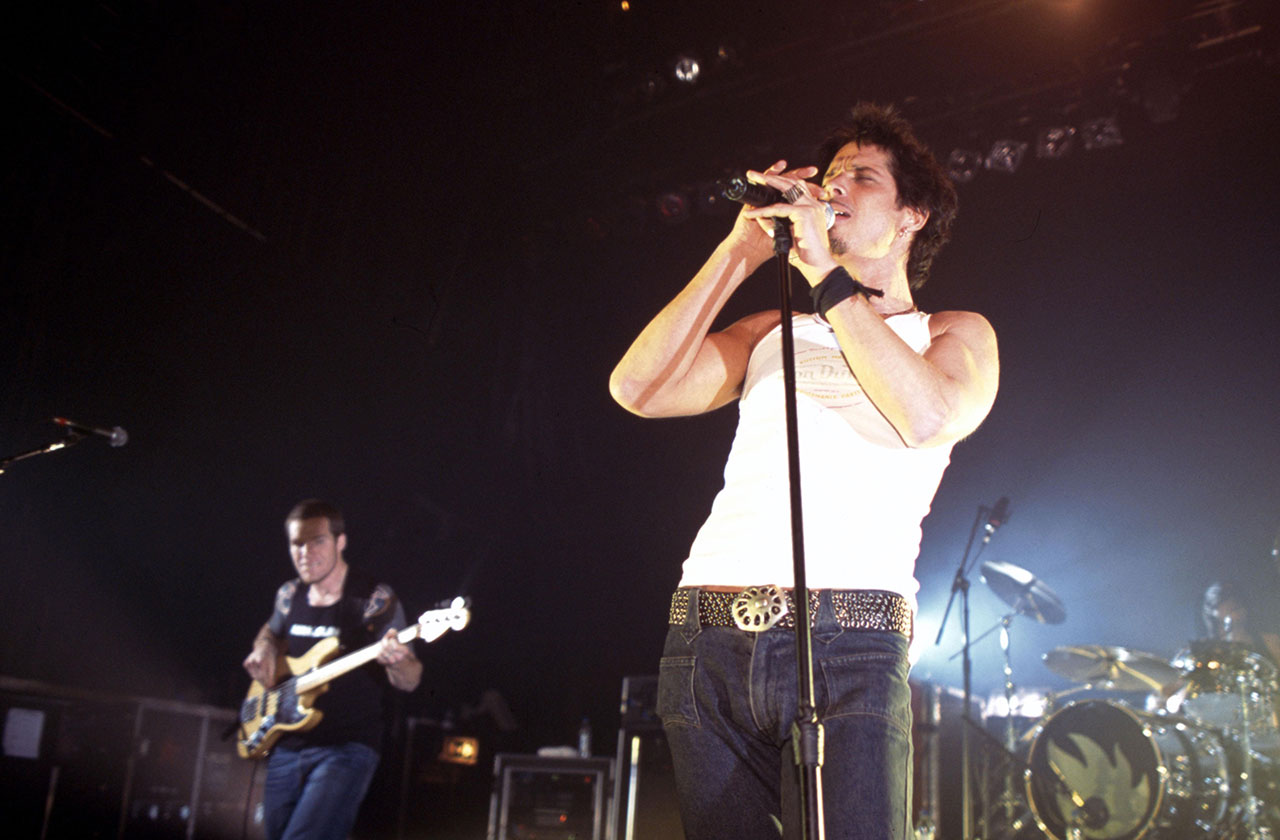

Cornell’s salvation would come from an unexpected quarter, though it wasn’t without its obstacles. When he was approached in 2001 about collaborating with Tom Morello, Brad Wilk and Tim Commerford, whose band Rage Against The Machine had recently split, he was initially reticent.

“At first I didn’t like the idea,” he admitted. “I hated the thought of joining three people who already existed in a relationship that was probably dysfunctional, because that’s the way all rock bands exist. But after jamming with them in a room, I was so impressed with how good they were.”

Still, this new union almost fell apart before the band – initially called Civilian, but eventually renamed Audioslave – had even got off the ground. Cornell’s drink and drug problems bottomed out while they were recording their first album.

“I was pretty much at my worst,” says Cornell. “I think they just looked at it as, ‘Oh, this is the kind of guy we have in our band now.’ I felt a sense of sadness and fear in them that made me wake up. It was being around people who weren’t part of the bad part of my life that I then saw how bad it was.”

Cornell checked himself into rehab, an experience he described as “like school; it’s interesting. I’m learning that I can be teachable at age thirty-eight.” There were other issues to be resolved, not least a dispute about the band’s management that saw Audioslave split up for a few weeks in 2002. But by the time they made their first live appearance, in December of that year, Cornell was thanking his new bandmates for saving his life.

“These three individuals as my friends really stuck their necks out for me and tried to help me… I think that brought us together, at least in my opinion, closer than any band I’ve been in before.”

While Audioslave’s music contained recognisable DNA from both parties’ parent bands, they were pitched as an old-school supergroup of the kind that grunge was supposed to have killed, even if Cornell himself never seemed comfortable with the rock god role that the position demanded.

Audioslave released three albums before calling it quits in 2007. Cornell confirmed the band’s demise in February of that year, at the same time as announcing his second solo album, Carry On. He put the split down to “irreversible personal differences”, although sources suggested he was unhappy with the “financial arrangement” within the group.

“At this point in my life I’m a person that probably shouldn’t be in a band,” said Cornell. “Someone that writes songs as much as me and has the energy and focus in terms of songwriting and performing is probably someone who’s more akin to a solo artist than someone who should be in a band.”

If Audioslave was a moderate success on a commercial level for Cornell, the five years he spent with the band were a personal triumph. As well as kicking booze and drugs for good, he met the woman who would become his second wife, Greek-American publicist Vicky Karayiannis.

The pair began a relationship after meeting in Paris during Audioslave’s first European tour. Cornell and Karayiannis married in 2004, and the singer reportedly converted to the Greek Orthodox Church. The pair had two children (Cornell already had a daughter with Silver), and parenthood was an increasingly prominent theme in his lyrics. He talked about having “a rekindled anxiety” at being a family man in his 40s.

“Having a wife and children that I see every day, and wanting these children to have a shot at a happy life and a future, I just have a sense of helplessness, and that anxiousness shows up in a number of songs. They’re about sort of, ‘What’s the state of the world and why?’ And I don’t like it.”

Still, all seemed to be going well professionally. In 2006, Cornell opened a swanky restaurant in Paris, Black Calvados, with his wife and brother-in-law. The same year he was invited to write the theme to the back-to-basics James Bond film Casino Royale. For Cornell it was a chance to properly engage with the mainstream in a way that even Soundgarden had never managed.

“I decided that I was going to sing it like Tom Jones, in that crooning style,” Cornell said at the time. “I wanted people to hear my voice. I knew I’d never have it again – a big orchestra – so I wanted to have fun with it. There’s an isolation in that; the stakes are very high. I’ve done a lot of living in my forty-two years, and it wasn’t hard for me to relate to that.”

For a man who despised the clichés of fame, Chris Cornell slipped surprisingly easily into the mainstream. His second solo album, 2007’s Carry On, bridged the introspection of Euphoria Morning with Soundgarden’s big-booted bombast, and even featured a cover of Michael Jackson’s Billie Jean. He toured separately with Aerosmith and Linkin Park, even joining the latter on stage to duet on the album song Crawling (that band’s singer Chester Bennington was godfather to one of Cornell’s children). Between 2007 and 2010 he worked with everyone from Slash and Carlos Santana to US pop singer Joshua David and Italian nu-jazz band Gabin.

But it was his collaboration with producer Timbaland on 2009’s Scream that became his most talked-about solo venture – albeit in the wrong way. Cornell had grown up listening to soul and R&B, and a chance to work with one of the biggest names in modern urban music was the sort of challenge he was looking for.

Cornell admitted that he and Timbaland had little in common apart from “blind trust”, and that was about the only ground they did share – despite his best attempts, his voice didn’t suit the restless electronic background, and vice versa. In hindsight, it was a bold attempt to shake up expectations, but at the time it was crucified by the media and fans. A tweet from Nine Inch Nails’ mainman Trent Reznor best summed up the reaction: “You know that feeling you get when someone embarrasses themselves so badly YOU feel uncomfortable? Heard Chris Cornell’s record? Jesus.”

“I expected it to get somewhat of a negative fan reaction, because it wasn’t going to be what anyone who was an old fan or a hard-core fan wanted to hear from me,” Cornell later said. “But having said that, I feel like there are a lot of people who only know that album from me and really love it, and there’s also fans of mine who over the years started to get into it.”

Ironically, it became Cornell’s highest-charting solo album, reaching the US Top 10.

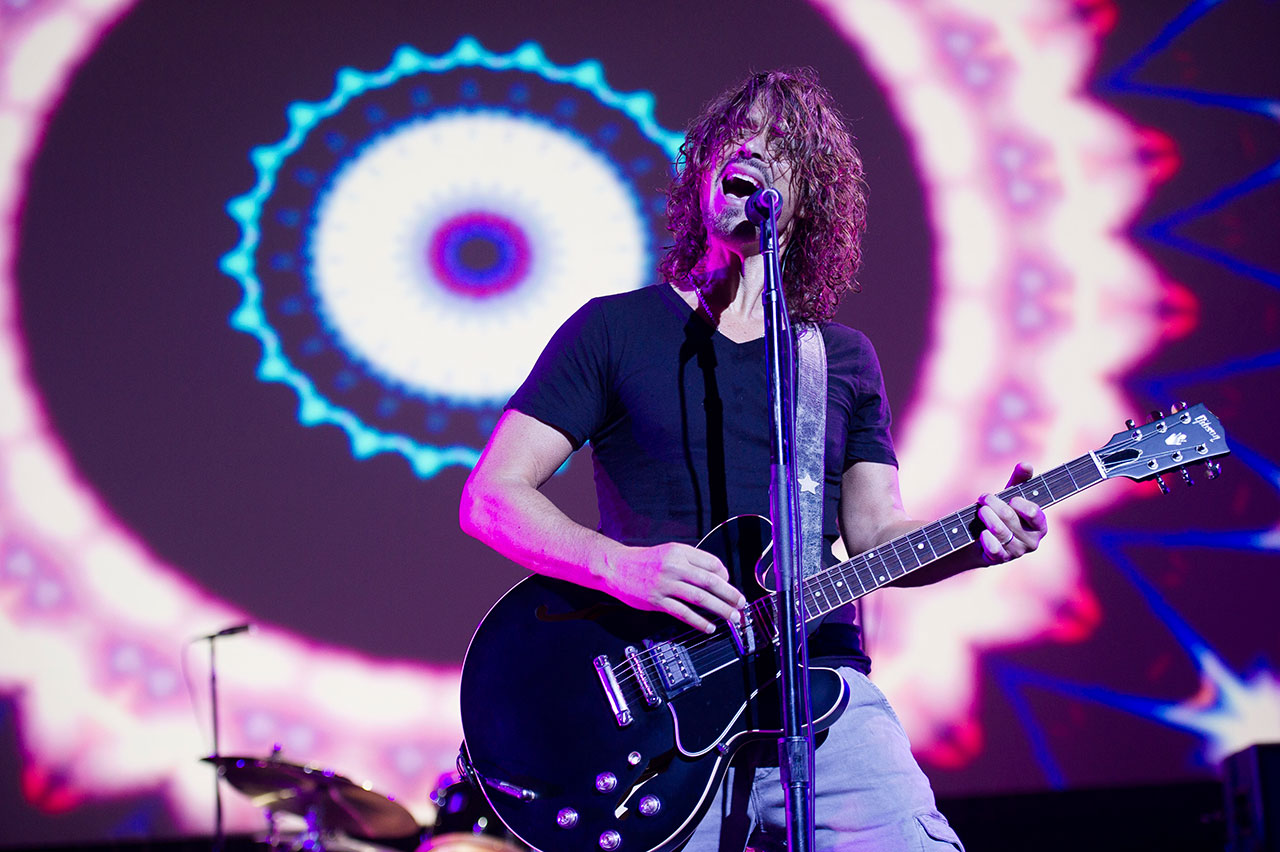

After the chastening experience of his Timbaland collaboration, Cornell retreated to the safest ground possible: Soundgarden. On January 1, 2010, the singer tweeted a semi-enigmatic message: “The 12-year break is over and school is back in session. Sign up now. Knights of the Soundtable ride again!”

Soundgarden guitarist Kim Thayil later claimed that it was promoting the band’s new website rather than a barely disguised announcement that the band were reforming. “But the rumours generated offers,” said Thayil. “The demand was overwhelming. I wouldn’t say we acquiesced, but we kind of warmed to the idea.”

If that was true, they warmed to it very quickly. Just three months later, in April 2010, the band played a reunion show at Seattle’s Showbox Theater under the anagrammatic name Nudedragons. Inevitably, this exercise in toe-dipping soon turned into a fully fledged comeback, one that took in a headlining slot at the 2010 Lollapalooza festival, an appearance on the soundtrack to the first Avengers film and, eventually, a brand new album, 2012’s well-received King Animal.

“It honestly felt like we’d just been on a break for a couple of years, not thirteen,” said Cornell. “Everything’s gone very smoothly.”

Cornell didn’t abandon his solo career this time. In 2011 he released the Songbook album, a career-spanning live acoustic album that acted as a restart after the Scream debacle. He continued in this stripped-back vein on 2015’s Higher Truth, a record that was inspired by Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska and Pink Moon by Nick Drake, the cult British folk musician who killed himself in 1974 at the age of 26. Even in his late 40s, it seemed the spectre of death was never far from Chris Cornell’s thoughts.

“I’ve lost a lot of young, brilliant friends, people that I thought were very inspired,” he told Rolling Stone Australia in 2015. “Andy Wood and Layne [Staley] and Jeff Buckley, who was a good friend, and Kurt [Cobain], and Shannon Hoon [of Blind Melon] was a friend, and Mike Starr [Alice In Chains] was a friend. These guys all had limitless potential in their lives in front of them… And to see that be the final chapter so young is a really hard thing to swallow every time.”

It’s easy to look back on Chris Cornell’s life and say that the clues were there all along. That’s true, but only with the benefit of hindsight. Certainly in recent times, he looked like someone who had finally found contentment.

In January 2017 he joined a reunited Audioslave for a one-off protest gig on the same day Donald Trump was inaugurated as President. In April he attended the premiere of The Promise, a film about the 1915-1917 Armenian genocide for which he had composed the mournful title song (his wife’s grandparents were refugees from the genocide).

Then there was Soundgarden. “We’re about halfway through writing the new album,” he told Billboard in April 2017. “We’re not on a schedule. What I look forward to the most is the camaraderie. It’s what we missed when we weren’t a band. When I do solo tours, I’m really kind of alone all the time, so that’s the best thing about it.”

Soundgarden were 11 dates into a US tour when they rolled into Detroit on May 17. Three days earlier, Cornell had tweeted happy Mother’s Day messages to both his mother, Toni, and Vicky. “You are an angel and a lioness,” he wrote to the latter. “The perfect mother and the perfect wife. I love you.”

Much has been written about Cornell’s performance at Detroit’s Fox Theatre the night he later died, some of it true (he did slip a line from Led Zeppelin’s In My Time Of Dying into the final song of the evening, Soundgarden’s Slaves & Bulldozers), some of it speculation (the band’s front-of-house engineer Ted Keedick told website TMZ that the singer seemed “fucked up”).

According to Vicky Cornell, her husband was slurring his words during a phone conversation the pair had shortly before his death, something the singer put down to taking an “extra Ativan or two”, referring to the anti-anxiety drug sometimes prescribed to former addicts.

That would be the last conversation Cornell had with anyone. Around 12.15am on May 18, a concerned Vicky called bodyguard Martin Kirsten, who kicked down the singer‘s hotel room door. He discovered Cornell dead on the floor of the bathroom. He had hanged himself with a red exercise belt.

When the news broke a few hours later, it prompted an outpouring of shocked grief. The grunge movement had seen its share of casualties, from Andrew Wood and Kurt Cobain up to Scott Weiland, but this was entirely unexpected. Jimmy Page, Aerosmith, Metallica and Pearl Jam were among those who paid tribute on Twitter. Over the ensuing days, his songs were covered by everyone from Slipknot’s Corey Taylor to jazz singer Norah Jones.

Chris Cornell was 52 when he died on May 17, neither a youthful Roman candle burnt out too soon like Andrew Wood or Kurt Cobain, nor an elder god whose time had come, like Chuck Berry or Leonard Cohen. But then depression, in whatever form it takes, is no respecter of age.

“I’ve had the last twelve years of my life being free of substances to kind of figure out who the substance-free guy is, because he’s a different guy,” he told Rolling Stone Australia in 2015. “And one of the great things about that is it enabled me to kind of keep going artistically and find new places and shine the light into new corners where I hadn’t really gone before. And that feels really good.”

Acts I and II of Cornell’s life had been by turns groundbreaking, uplifting chaotic, unexpected and ultimately troubled. The great tragedy is that we’ll never get to know what Act III held.

Remembering Chris Cornell: The early years

Chris Cornell’s widow Vicky writes open letter to late singer

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.