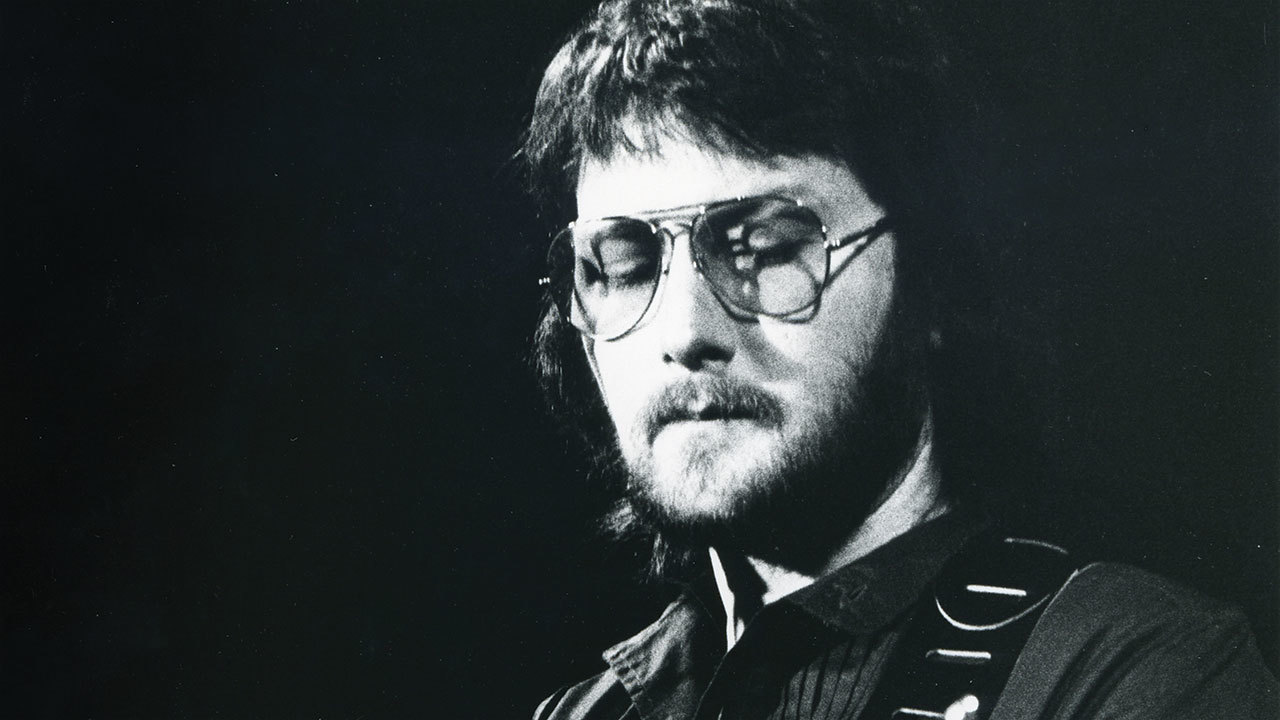

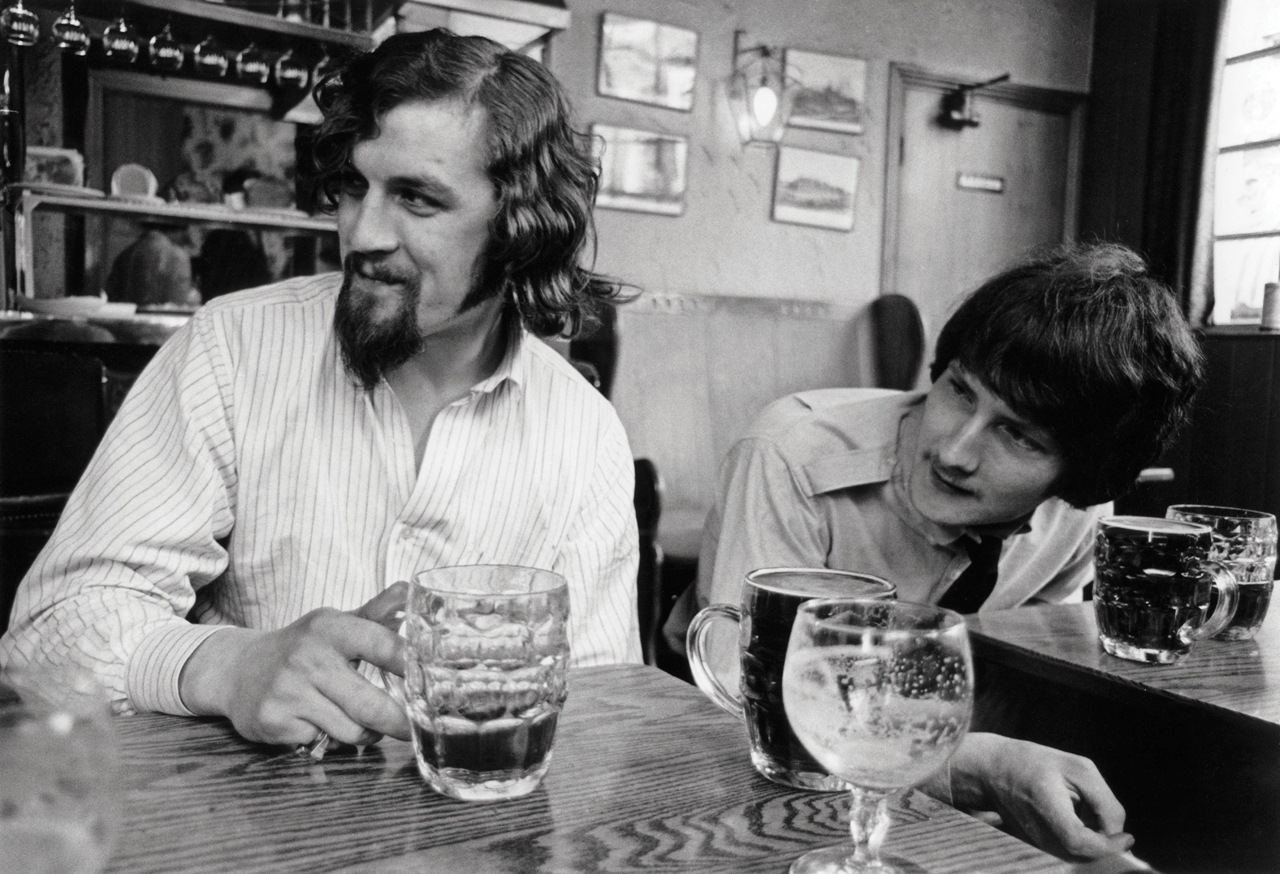

Of all the many songs that Gerry Rafferty wrote, the one that made him famous was drawn from a thoroughly humdrum experience. For the better part of three years, Rafferty had to slog down from his native Scotland to London, so often he could trace the route with his eyes shut, to sit with a gaggle of lawyers, poring over the fine print of a potentially ruinous contract he had signed up to when he was with his old band, Stealers Wheel. The light relief in these forays were the times at the end of a day when he would meet up in the pub with his friend and fellow musician Rab Noakes and drink to their better fortune. The two men’s regular London boozer was called the Globe and located at the junction of Marylebone Road and Baker Street.

“He was a pretty erudite character,” says Noakes. “One of those people, from the post-war consensus, who’s bright as a button, but that didn’t do all that well academically. We had some great times with long conversations into the night.”

Rafferty had travelled an otherwise scenic route to this point in the mid-1970s. Beginning with beat groups in his hometown of Paisley, a satellite of Glasgow, he had been making his living playing music for going on ten years. Next he had dipped into the fertile Glaswegian folk scene, joining a colourful young local character named Billy Connolly in a duo called The Humblebums. Those had been good times, but not so as each of them didn’t want for something more and on their respective terms. Connolly was a born comic, the more introverted Rafferty minded to forge a different path. In 1971, he split from Connolly and made an accomplished solo album, Can I Have My Money Back? that got good reviews, but hardly sold.

Back to the bosom of a group he went, forming Stealers Wheel with an old running mate from Paisley, Joe Egan. This time success was huge and instant, a smash American hit with a song Rafferty had meant as a parody of Bob Dylan, Stuck In The Middle With You. Soon enough, though, things turned sour for Stealers Wheel. After the hit had proved a one-off, their management company filed for bankruptcy, leaving the band’s royalties unpaid and Rafferty and Egan in a state of contractual limbo, each restricted from writing or performing. Rafferty fled home to Scotland to lick his wounds and settle to the grinding routine of an attritional legal battle.

Determined ever after to be his own man and at all events, Rafferty set himself to writing songs for a second solo record. He taped them onto a four-track Teac recorder in the various houses he rented through the period in Clydebank, Skelmorlie and Kilmacolm, road-testing them on drives into Glasgow with wife Carla and their young daughter Martha aboard the family’s small Honda Civic. Listening to his own songs would always seem to comfort Rafferty, soothe whatever might be hounding him. Punk was rampaging out of London’s pubs and clubs and Rafferty’s intricately detailed songs flew in the face of the prevailing winds, but he didn’t for a second doubt their worth.

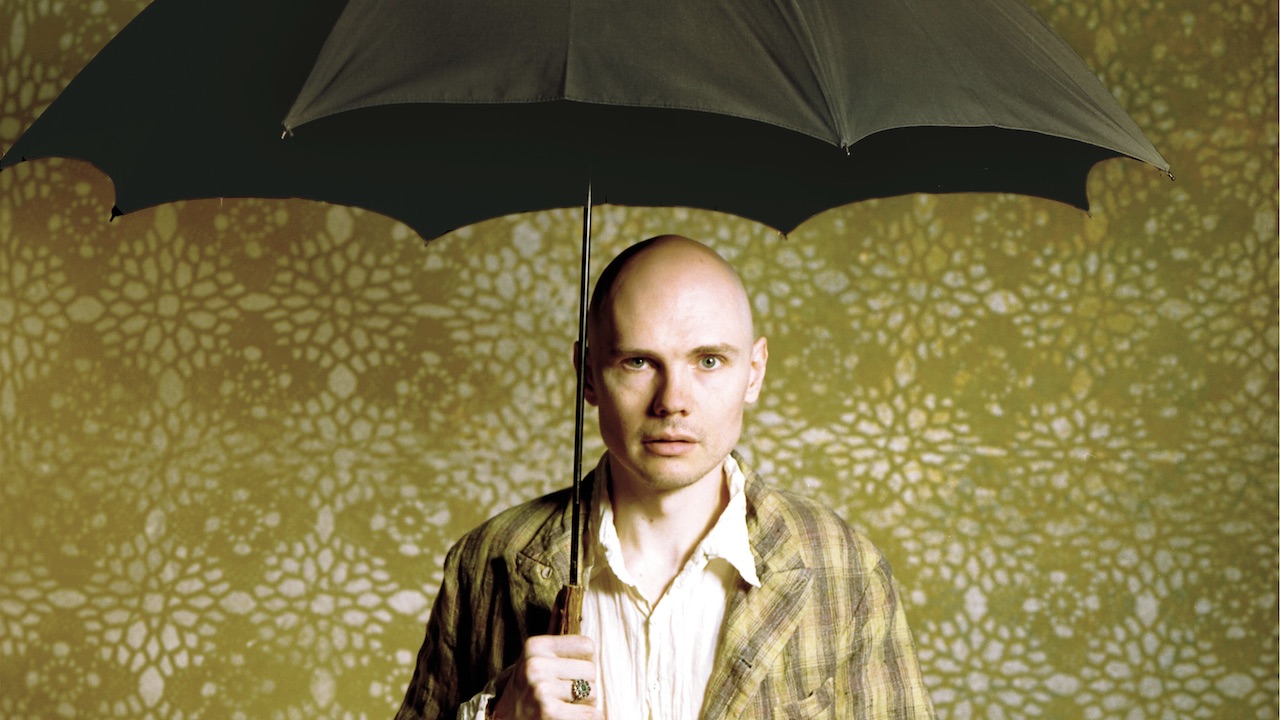

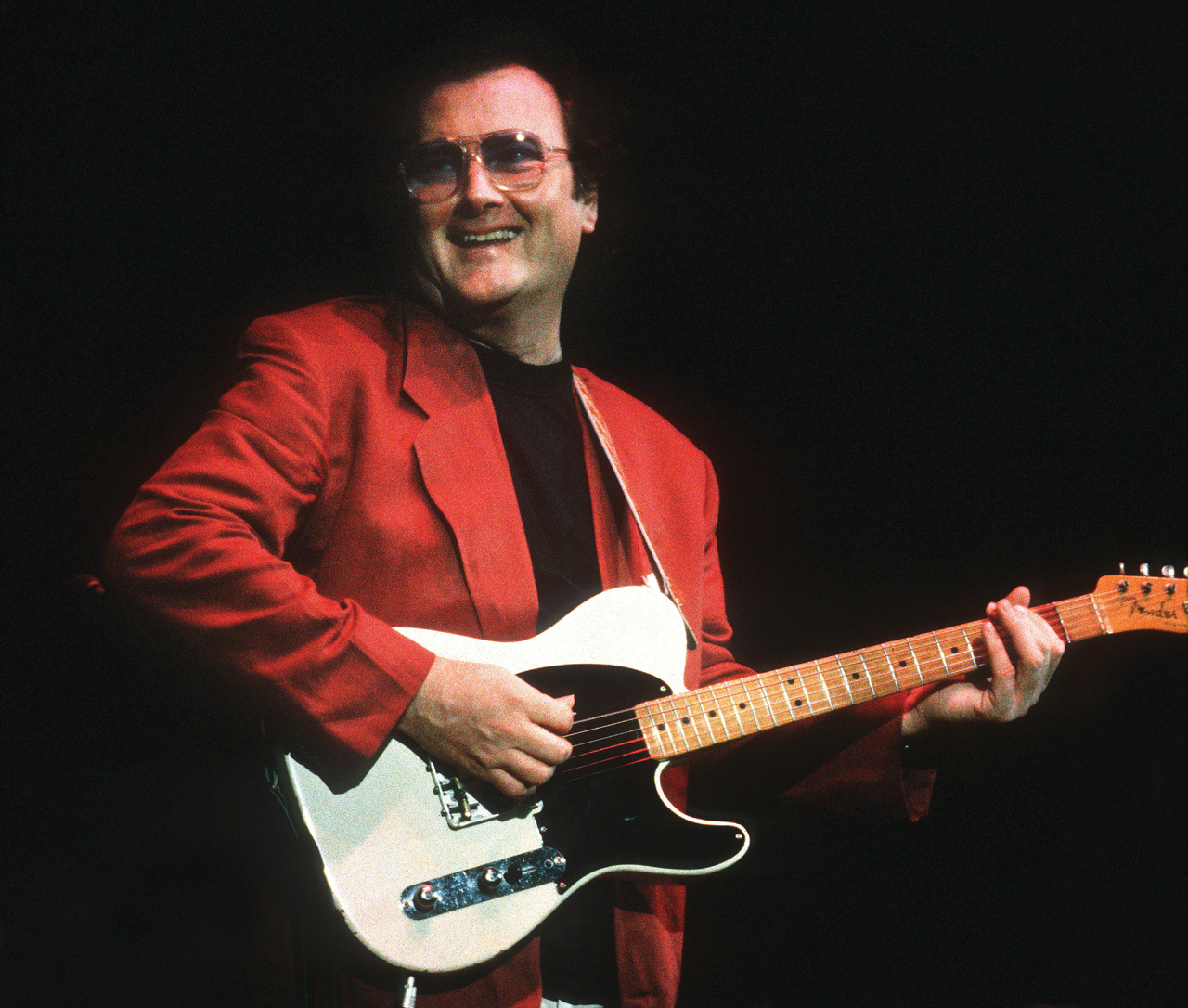

The title of the album he eventually cut was also derived from his protracted spell commuting – City To City. A Beatles nut, he fixated on strong melodies and the ten featured songs had that much in abundance. Rafferty was also blessed to be able to sing them in a voice that had both McCartney’s sweeter registers and Lennon’s raw passion. Baker Street was one of the last songs he wrote for the record and just as his contractual dispute was being settled. That much seeped into the optimistic last lines of the song: ‘And when you wake up, it’s a new morning/The sun is shining it’s a new morning/And you’re going, you’re going home.’ These were given wings by the album’s most distinctive melody line and which burst up throughout the song. Rafferty had originally written it for guitar, but when that didn’t soar – and at producer Hugh Murphy’s prompting – he summoned an unheralded session player, Raphael Ravenscroft to the studio to put it down instead on sax.

Initially, Rafferty’s new label, United Artists were set against releasing Baker Street as the album’s lead-off single. Rafferty and Murphy practically had to beg them to put it out, but once they did on February 3, 1978, the song took off like Ravenscroft’s spiralling saxophone. Baker Street rose to Number Three on the UK chart, went one higher in the US and won Rafferty two Ivor Novello awards. He got a telegram from McCartney congratulating him on “an incredible song”. Off the back of it, City To City sold five and a half million copies and knocked the Bee Gees’ until then all-conquering Saturday Night Fever soundtrack from the top of the Billboard chart in the States. The insular Rafferty wryly noted how he had become an overnight sensation from doing what he had for a decade. Altogether, no aspect of his life would ever again be the same.

“I don’t believe he had any particular expectations that he would have such enormous successes commercially,” says Michael Grey, head of press at United Artists when City To City was released and who Rafferty brought in as his manager. “The album had sold more than four million and he didn’t even have a manager. Mad promoters from Utah would be ringing him in the middle of the night and demanding that he tour. He wasn’t in need of a Svengali. Quite the opposite, he needed someone to more or less answer the phone. From my side of things, the main problem was that basically he wanted me to say no to everything.

“I liked him straight away. He was very guarded, but I could understand that. I had seen many sides of the record business by then. He was very sure of his own talent and equally suspicious of how it would be exploited.”

“When Baker Street became the hit that it was, adults changed towards me,” recalls Martha Rafferty. “They smiled more, gave me bigger portions of food at school lunches, and I remember feeling how fake and phony people became. Children see things as they really are.”

The sound of Baker Street would become as emblematic of the era as any of Queen’s excursions into mock-opera, the Eagles’ sun-blushed harmonies, the Bee Gees’ stratospheric disco or Johnny Rotten sneering ‘God save the Queen’. In 2003, Rafferty was quoted as estimating that the song was still earning him £80,000 a year. The actual the actual figure, however was much higher. It never went away, but neither was Rafferty able to get out from under the looming shadow the song cast, or seem to escape the demons in him it appeared to amplify. When he died on January 4, 2011, aged sixty-three, his work had made him a millionaire, but the considerable due he merited as a songwriter of rare craft and intuitive skill had largely eluded him.

“He was a titan, a giant,” opines Barbara Dickson, who sung with Rafferty in Glasgow’s folk clubs and contributed backing vocals to City To City. “He could have been as famous as any songwriter in the world, but chose not to be. One thing I do know is that James Taylor wrote Gerry a fan letter about another song on City To City, Whatever’s Written In Your Heart. I rest my case.”

The town where Gerald Rafferty arrived into the world on 16 April 1947 is six miles from Glasgow, but prides itself on being apart from the city. Rafferty’s friend, the painter and playwright John Byrne, describes the two places as being as different as chalk and cheese, suggesting Glasgow more generally breeds stand-up comics and Paisley oddballs. Rafferty was the youngest of three sons born to Joseph and Mary Rafferty. Fairly typically of Paisley at the time, they were a working class family. Rafferty grew up in a ground-floor tenement on one of the town’s sprawling council estates.

His father was of Irish stock, a lorry driver by trade and a heavy drinker. Writing Rafferty’s obituary for The Guardian, Michael Grey claimed that Mary Rafferty would regularly whisk her youngest son from the house on a Saturday night and so as to be out of harm’s way when Joseph got home drunk. Joseph Rafferty died when Gerry was just sixteen, but if he bequeathed anything to his last-born son it was an affinity for songs in the Irish and Scottish folk tradition. From knee high, Rafferty would sing these standards, three-part harmonising with his elder siblings, Jim and Joe.

At eleven, he started to play. Jim Rafferty worked with John Byrne as a ‘slab boy’ in a poky back room at the local Stoddard’s carpet factory, grinding up coloured powder for the carpet designers. Byrne would later write his trilogy of famous plays The Slab Boys about this experience. The future playwright would take a three-string banjo with him into work, hanging it under a dust coat behind the door.

“Jim and I became pals and spent a number of evenings at each other’s houses,” takes up Byrne. “One day, Jim asked if it was okay for him to borrow the banjo. He said his little brother wanted to teach himself a Cliff Richard tune. Gerry was very quiet, very shy. I spent a year in the slab room before getting a place at Glasgow School of Art, and didn’t see much of him until some years later when I was married and he was playing in a band.”

Upon leaving St Mirin’s Academy school at fifteen, Rafferty had gone to work as a butcher and then in a shoe shop. By then, the Beatles had already begun to change the world and Rafferty, like countless other British teenagers, was intoxicated by the very idea of having a band of his own. The first that he joined was the Mavericks, through which he met Egan, who was nominated by the fledgling group as lead singer, and together they bashed out Beatles and Stones covers around the local dancehall circuit on weekends.

Further inspired by the example of Lennon and McCartney, Rafferty and Egan began to write their own, mop-top-styled songs. As his muse, Rafferty had Carla Ventilla. Dark-haired, pretty and fifteen-years-old, Carla was from an Italian family and worked as an apprentice at her father’s hairdressing salon in nearby Clydebank. The two of them had met at a dance and after which became inseparable, much to her father Tony Ventilla’s disgust.

“To Tony, Gerry was a total ne’er do well,” says John Byrne. “He wasn’t at all happy when Gerry started to go steady with Carla. For a few months, Carla had to come to lodge with me and my then wife, Alice and we saw a great deal of the two of them.”

From the Mavericks, Rafferty and Egan progressed to another beat group – a quintet, the Fifth Column – so as to be able to play their own songs. They got as far as landing a deal with Columbia Records and in 1966 cut a Rafferty-Egan original, Benjamin Day. More Byrds-influenced with its jangly guitar line and whimsical sense of psychedelia, it was released by the label as a single but flopped. Rafferty struck out on his own, casting back to the folk songs of his childhood for renewed inspiration. Fortuitously, it wasn’t long before he got introduced to Billy Connolly at Paisley’s Orange Hall, where the latter was playing with partner Tam Harvey as the nascent Humblebums. Native to Partick, Glasgow, Connolly already had a notably larger-than-life personality. In this respect, he was entirely opposite to Rafferty.

“He was a raging extrovert and I was the sensitive singer-songwriter,” Rafferty told BBC Radio Scotland in 2003. “Yet we each shared a sense of the absurd and a way of looking at life, so that we did a lot of laughing. That night, we went back to a mutual friend’s place and where I played Billy quite a few of my songs, which he thought wonderful.”

Barbara Dickson was similarly bowled over by Rafferty’s blossoming as a songwriter. Then making her way as a young folk singer, Dickson happened across Rafferty performing solo one night at Glasgow’s Scotia Bar, a wood-beamed, River Clyde-side Mecca for the local folkies.

“I remember being completely transfixed by him,” she says. “It was very rare for me to feel that way, but he was fantastic. Somebody told me he was a mate of Billy Connolly’s. We started to hang out together. Gerry was a huge personality and a big man. He had a laugh like a machine gun and a fantastically infectious smile. He was wonderfully expansive in his gestures, yet terribly shy which made him devastatingly attractive of course.

“I wasn’t the only person to discover Gerry at that time. Hundreds of other people were listening to him around Glasgow, but it was a seminal moment in my life and not just in music.”

Connolly, who says Dickson thought Rafferty “the best thing since sliced bread,” didn’t waste time in inviting his new friend to join the Humblebums. Though Harvey left soon after, Connolly and Rafferty would remain partners for the next couple of years. They toured the country, their act a simple, but effective one, with Connolly telling jokes in between Rafferty’s songs. They also made a brace of likeable albums together, 1969’s The New Humblebums and the next year’s Open Up The Door. Rafferty reflected later that the time he spent with Connolly was the most he ever enjoyed being on the road. “We travelled light – just an acoustic guitar and a banjo,” he said. “And for a concert I suppose we got £100, which was cash-in-hand.”

“I was asked by Gerry and Billy to do an illustration for the cover of The New Humblebums,” says Byrne, who would go on to provide the artwork for all the Stealers Wheel albums, and both City To City and Rafferty’s follow-up to that album, Night Owl. “At that time, Alice and me, Gerry and Carla were very fond of dining together at the Rogano, a long-established, Art Deco seafood restaurant in Glasgow. We would eat, talk, laugh and drink the entire night away and with instructions from the staff to pull the door closed behind us when we quit the joint and which would be as the sun was coming up next morning.”

Eventually, and as Rafferty related it, Connolly’s jokes got to be longer, the time allocated to his songs exponentially shorter, and inevitably the two men broke apart. Rafferty’s subsequent first solo album might not have won him a bigger audience, but with it he forged a solid bond with Hugh Murphy, then employed as staff producer for his label, Transatlantic. It would be six years before the pair of them next worked together and after which Rafferty had enjoyed and then endured his initial taste of fame.

By 1972, Rafferty had moved his family to Tunbridge Wells in Kent. It was to there that he gathered about him the musicians who would make up the first line-up of Stealers Wheel. Joe Egan also moved down south from Paisley; Roger Brown, an American who’d been a member of the Humblebums backing band, joined him, as did Rab Noakes who Rafferty had become acquainted with on the Glasgow folk circuit. Rafferty had a piano set up in the front room, around which he and Egan would write songs.

“That was a tremendously fertile period,” explains Noakes. “The house was full of songs the whole time, morning, noon and night. Someone would pick up a guitar and start singing and other people would join in. You wouldn’t call Gerry the leader of it, but it was his vision that brought the whole thing together.

“Gerry and I did a flurry of shows around the area in the summer of 1971. It was a two-voices-and-guitar kind of thing. He’s probably the person that I’ve loved singing along with more than anyone else. Yes, he was complex, but also deep, thoughtful and highly creative. He had a large degree of self-determination. Some people can find that kind of focus a wee bit difficult to deal with, but to me it was hugely inspirational.”

Not that this state of creative bonhomie was made to last. After the band were signed to A&M, the label insisted upon drafting in new musicians to work around Rafferty and Egan and also paired them with veteran producers Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, famed for their association with Elvis Presley. The revered duo’s working partnership with Stealers Wheel was not nearly so well defined. In particular, Rafferty was unsettled by Leiber’s and Stoller’s strictly old-school approach to making records.

“I think he viewed us as the enemy,” Stoller observed years later. “There was something very distasteful to him about us, what we represented to him, crassly commercial, what have you. Gerry was difficult to work with from the get-go.”

Nonetheless, propelled by Stuck In The Middle With You, Stealers Wheel’s debut proved to be both a creative and commercial success. The band was made to tour relentlessly behind it, prompting Rafferty to quit, claiming later that he had been on the edge of a nervous breakdown. He was persuaded to return to make 1974’s Ferguslie Park album, named after a notorious Paisley estate. With nine musicians backing Rafferty and Egan, it was lush and extravagant, but didn’t sell. A third album, Right Or Wrong, followed in 1975, but by that point Stealers Wheel was already over, broken on the wheel of their own internal bickering and the collapse of their management. The whole experience coloured Rafferty for the rest of his days.

“He was obsessed with keeping control,” opines Barbara Dickson. “And he didn’t trust anybody in the music business. By definition, if they were in the business they were a bunch of shits and he thought they were going to feck him over. His work and his world were very precious to him. Also, he saw himself as a serious writer, which indeed he was, but being a pop star is a Faustian pact. You cannot start dictating the terms two years into it.”

A pop star was just what Baker Street and City To City turned Rafferty into. A year later and also with Hugh Murphy, he produced a second hit album, Night Owl, which with its title track and Get It Right Next Time matched the mercurial Steely Dan for sophisticated pop perfection. Rafferty himself was not so clear cut. In some respects he pushed against the tide, most obviously in refusing all entreaties to tour behind either record in the US. On the other hand, he fully enjoyed the fruits of his success. He bought a rambling farmhouse and three-hundred acres of land in rural Kent and a grand Queen Anne house in London’s upmarket Hampstead. Required on one occasion to travel to America, he flew by Concorde.

“He liked having money and status, and why shouldn’t he have done?” considers Barbara Dickson. “He had an image of himself being almost like an American rock star and that was okay. He was always well off and drove nice cars, and coming from a very humble upbringing he felt that was an achievement I’m sure.”

“Sometimes he would want to sit in the bar at the airport, miss his flight and just get on another a couple of hours later,” furthers Michael Grey. “That’s the main thing I feel bad about, although I’m not sure what I could have done really. When he would say, ‘Oh, let’s not go to the gate for this one, let have another drink,’ it never occurred to me that he was on the road to becoming an alcoholic. Everybody drank and took drugs in those days, but Gerry wasn’t nearly such a nice man when he’d had a certain amount of whisky.”

Of Rafferty’s golden period, there were a couple more fine records –1980’s Snakes And Ladders and Sleepwalking in 1982 – and then six years of silence. He had a studio built at his Kent farmstead and continued to make music, but otherwise spent the time away travelling in Europe and America, and also, according to Martha Rafferty, being engaged on a more personal quest.

“His real journey was an inner spiritual one,” she says. “He wanted to understand why we were here. I don’t think he felt as if he was shutting himself off from anything of great value. He was disillusioned with the commercial aspect of making music to sell product. He made records because he had to. He was driven to create; it’s what helped him put his inner world back in order.”

Towards the end of the decade, Rafferty did come back. With Hugh Murphy, he co-produced one last hit, Letter From America for Scots duo the Proclaimers. In 1988, there was also a new solo album, North And South, a more low-key, introspective echo of former glories, but it was met with some scathing reviews. His drinking had escalated too, to the degree that it became debilitating and damaging. In 1990, his beloved Carla left him. There were other punishing blows to his psyche. His brother Joe died in 1995, then Hugh Murphy in 1998, each devastating him and appearing to hasten his own decline.

“Carla loved him till the day he died and he loved her, but she couldn’t believe what happened to him,” says Barbara Dickson. “There was nothing anybody could do for Gerry. Carla was the closest person in the world to him and she wasn’t able to help. Alcoholism is a terrible sickness.”

There were just occasional records after that, three in all. Intermittently on each Rafferty’s wondrous grasp of melody could still be heard, almost like a reflective spasm. He was even indirectly returned to the spotlight in 1992 and when Quentin Tarantino chose his old Stealers Wheel hit to soundtrack the infamous ear-slicing scene in his searing crime caper, Reservoir Dogs. Rafferty didn’t bother to watch the film until nearly twenty years later.

He went with Martha to live in California for several years, for a spell joining a group devoted to the teachings of Russian-born philosopher and spiritualist George Gurdjieff. He could not stop drinking, though. Back in the UK in November 2010, he was rushed into hospital in Bournemouth suffering from multiple organ failure and put on life support. He was not expected to make it through the night, but rallied enough to be able to spend that Christmas with Martha and his grand-daughter at their home in Stroud, Gloucestershire. It was to be his last Christmas.

“He was dying and we both knew it, and it was okay,” says Martha. “During that time, we both made peace on many levels. When my mum left, Dad was dependent on me to function. I did my best to hold things together, but it was very difficult and he lent on me heavily, psychologically and emotionally. His journey to death was the most profound thing I’ve ever witnessed.”

“I was living in Edinburgh and heard from Martha that her dad was very poorly,” remembers John Byrne. “I got on a train to Stroud and picked up a taxi which skidded its way in pitch blackness to where Gerry was living with Martha. There, in the middle of nowhere, Gerald and I blethered, laughed and shot the breeze for a good five or six hours’ non-stop. He was perfectly coherent and ready to quit this world for the next.

“Two days later, Martha texted to say her dad had slipped peacefully away. He was a genius and dear friend who left a priceless gift of wonderful songs to all of us. He went through Hell and arrived at his final destination with a sense of peace and fulfilment, but what a journey!”

A requiem mass for Gerry Rafferty was held at St Mirin’s Cathedral, Paisley on January 21, 2011. John Byrne gave the eulogy before four-hundred mourners and among them the then-First Minister of Scotland, Alex Salmond. That same month, Celtic Connections in Glasgow hosted a remembrance concert, at which Noakes, Dickson, the Proclaimers and Jack Bruce played. The following November, his hometown paid a still more lasting tribute, naming a street in the Shortroods area Gerry Rafferty Drive.

Outside of Scotland – and same as it ever was – it’s the sound of that resigned vocal and eruptive saxophone that still now most readily brings Gerry Rafferty to mind. Better, more representative songs would be Shipyard Town from North And South – a rousing version of which Jack Bruce performed at that Glasgow concert – the stately The Right Moment, or any of the other deep, soulful songs on which the big bear of a man from north of the border with the aching voice and too-wounded heart bared himself.

“For me, he’s the greatest ever Scottish songwriter,” maintains Barbara Dickson, who released her own tribute album to Rafferty in 2013. “It was an honour and a privilege to have even known and been close to him in any way. When he died, I cried and cried, but whenever now I get sad about him not being here, I say to myself that it’s better to have had a part of him than not to have had him at all.”

“I will be forever in debt to what Dad gave me,” Martha Rafferty concludes. “There were so many indescribable experiences. Every day was a journey in itself and I’m still recovering from the impact those years had on me.”

Stealers Wheel: The A&M Years is out now via Caroline International