“You can’t shine if you don’t burn!” Remembering Kevin Ayers

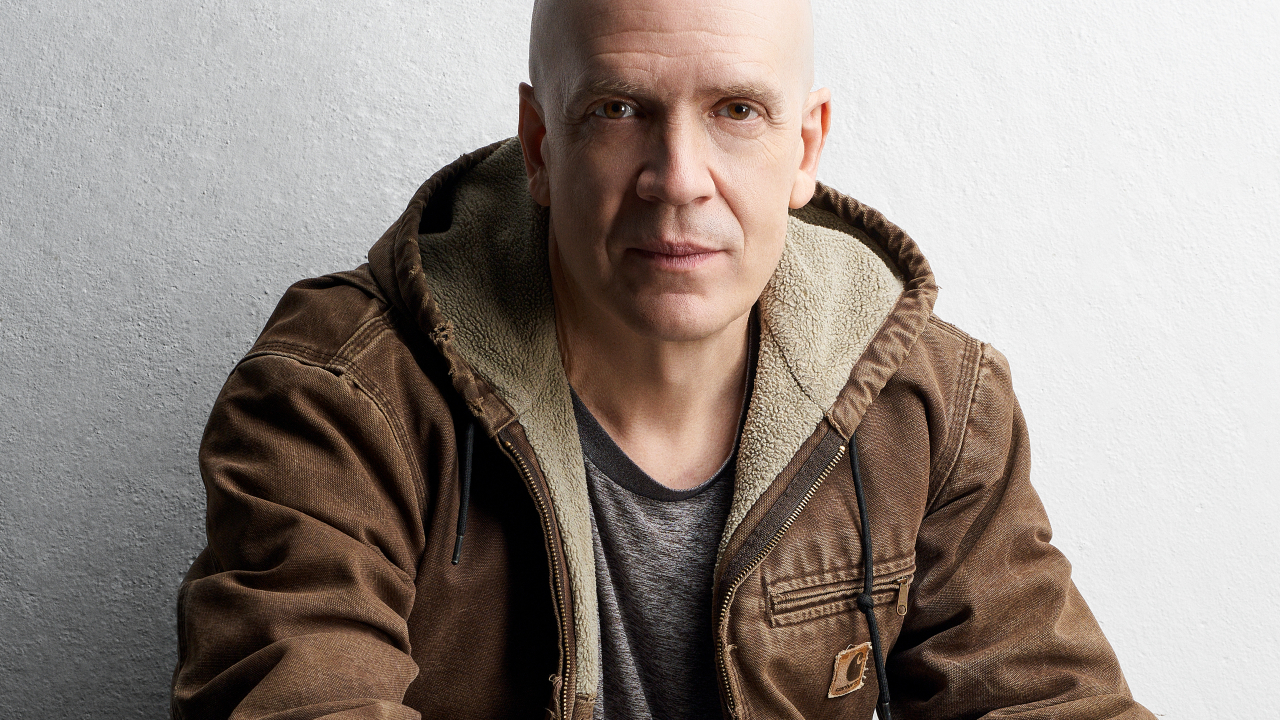

Prog Editor Jerry Ewing remembers a lifelong enjoyment of Kevin Ayers' music and his meetings with the great man

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

‘I’ve got no ambition, guess I’m out of place, Cos I’d rather go fishing than run in the race, I’m naturally lazy but what can I do? I was born in the wrong place, wrong time too…’ Kevin Ayers, Am I Really Marcel? from Falling Up, 1988

I met Kevin Ayers three times. Given he spent 68 years on this planet, that might not seem like much, but believe me, for a dedicated fan of his irregular talent and idiosyncratic quirk, it was more than I’d dared hope for. Not least because of Ayers’ own nonchalant approach to the machinations of the music industry, which at one point in his chequered but mesmerising career he summed up quite eloquently, and with almost painful honesty, in our opening quote. It’s a line from a song on Falling Up, his 1988 album that saw him reunited with Mike Oldfield, a man who Ayers tutored as a very young musician. Oldfield was in his band for Ayers’ first two solo albums, Joy Of A Toy (1969) and Shooting At The Moon (1970).

But then if you read the many obituaries that have appeared in the broadsheets paying homage to the man who helped form Soft Machine and instigate what we now call the ‘Canterbury sound’, one thread always stands out beyond Ayers’ own charming talent (once described famously by John Peel as being “so acute you could perform eye surgery with it”). It was his reluctance to indulge the fame game, frequently dipping out of public view just as some kind of career momentum seemed to be getting up a head of steam.

Article continues belowThe first of those three times we did meet, at an aftershow party at a rare 1988 London gig, typified this fact. Having seen a photo of this most unique of artists in the Sounds Hippie Chart, I’d decided anyone who looked so casually unconcerned by life and its travails must be worth seeking out. And so I did. At that point, making my way in a decidedly foreign England after years growing up in the relaxed confines of 1970s Sydney, anything that offered a slightly quirky take on the pub-rock groove I’d grown up with helped mould my desire to discover music anew.

Ayers, while not uniquely prog rock, still helped open the door to the vast sonic landscape we all now cherish.

I can actually remember my very first Ayers purchase. In the early 80s, Ayers was very much off-radar. Having recorded his final album for the Harvest label (1980’s That’s What You Get Babe), he retreated again to the sunnier, laid-back climes of Spain while struggling with addiction issues. Indeed, he was almost wholly overlooked – a situation he would have perversely enjoyed no doubt.

Still… Wembley market. 1977’s Yes We Have No Mañanas (So Get Your Mañanas Today) – a US import on the ABC label I still have to this day, and indeed am listening to as I write this piece. Ayersologists (if such a thing exists) will tell you that Kevin’s output post-1974’s quite exhilarating The Confessions Of Dr Dream, is rarely worth bothering with. Ayersologists are wrong. True, the output is patchy, but there are still gems to be discovered.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Anyway, out of the blue, in 1988 Ayers featured on his old friend Mike Oldfield’s Islands album. At the time, Oldfield was given to working with different vocal artists, and had, no doubt after much cajoling, enlisted Kevin to sing on the track Flying Start. It’s an almost biographical take on Ayers’ own career, featuring as it did the lines ‘Did you find your chateaux in that Mediterranean fantasy’ and the more damning ‘So you lost your dream in a bottle of wine, I know you had to do it your way fine, but there’s none to carry the cross this time.’ Ayers even featured in the promo video (check it out on Oldfield’s Elements DVD collection), suitably attired in sunny climes and with that ever-present bottle of wine.

Although Oldfield was reluctant to admit it when I once asked him at his Buckinghamshire enclave if he’d set the deal up, Ayers signed to Virgin Records (Mike’s label at the time) and released his own album, Falling Up. It was undoubtedly his best and most cohesive work for over a decade, and despite scant promotion, he actually played a UK gig – at London’s Queen Elizabeth Hall (annoyingly the same night as Arlo Guthrie played a rare show at the Royal Festival Hall next door). I pestered my mate Adrian into coming along with me (he remains one of many people I’ve introduced Ayers’ music to who’s utterly enthralled and equally agog that so few people seem to be aware of his output), and we sat, admittedly stoned, in utter awe as this charismatic and idiosyncratic musician plied his trade.

With his long-standing musical cohort Ollie Halsall on guitar (ex of UK prog rockers Patto), it was a spellbinding experience and the poster purloined from the venue remained on my bedroom wall for many years. Somehow we even blagged our way into the aftershow party, at which a slightly uneasy Ayers signed said poster with a “Why on earth do you want me to sign this?”, embodying his whole attitude to that fame game.

Halsall died of a drug overdose in 1992, having completed work on Ayers’ next release, 1992’s largely acoustic Still Life With Guitar. The loss of his long-time musical foil clearly affected Ayers. Despite this, he made a return to active live work with a selection of Belgian acolytes, which saw Ayers appear at London’s Borderline in 1992 and 1993. The latter which saw me, this time in work mode, seated supping a pint with this enigmatic hippie on the steps of the Soho pub The Pillars Of Hercules, where we discussed his career but, perhaps more pointedly, watched the world go about its business in the warm sunshine. The same year I caught him at the short-lived but quite wonderful Canterbury Rock Festival, and his live activity was upped with the involvement of Liverpudlian psych rockers The Wizards Of Twiddly later the same decade.

Although I’d never see Ayers perform again after that, our paths crossed once more in a pub near Westbourne Park tube station, near the home of Bernard MacMahon, co-founder of LO-MAX Records, a small independent label. He’d managed, with the help of artist and Ayers’ friend Timothy Shepherd, to get Kevin back in the studio to record his final album, The Unfairground, released in 2007. Given the ignorance that clouded his career in the 80s, this time the likes of Teenage Fanclub and Gorky’s Zygotic Mynci were champing at the bit to work with their inspirational hero, while long-time friends and colleagues like Robert Wyatt, Phil Manzanera, Hugh Hopper and Bridget St John also helped out.

Over the course of an evening, and long after the interview tape ran out, we lazily discussed his career and its rightful place in the pantheon of music. Kevin was typically recalcitrant to accept his own part in the scheme of things but, when alcohol had coloured proceedings, he talked joyfully of touring with Hendrix (which he’d done with Soft Machine in America in 1968) and the kinship he genuinely felt with fellow idiosyncratic musos like Roy Harper, John Martyn and his one-time friend Syd Barrett, for whom he wrote the song Oh! Wot A Dream, and who featured on the original version of Singing A Song In The Morning from Joy Of A Toy, entitled A Religious Experience (along with several members of Caravan). Yet he remained genuinely perplexed that people retained an interest in his own musings. Walking him back to MacMahon’s nearby flat, it never entered my head that we’d never get the chance to speak again.

Kevin Ayers died in his sleep on February 18. He’d remained out of the public eye since 2007, no doubt an irritation to LO-MAX in the same way his reluctance to play the star was to Elton John’s manager John Reid, who in 1975 had decided Ayers’ louche good looks could make him the next star (just listen to that year’s Sweet Deceiver, which features Elton on piano, to hear Ayers’ thoughts on that issue!). He once said, “I think you have to have a bit missing upstairs, or just be hungry for fame and money, to play this industry game. I’m not very good at it.”

It said everything of the man who pioneered progressive music and along the way worked with the likes of David Bedford, Caravan, Daevid Allen, Nico, Eno, Andy Summers, Archie Leggett, Lol Coxhill, Didier Malherbe, Pierre Moerlen and Danny Thompson.

Ayers’ wonderful musical legacy, along with much of the music made by his peers, makes a mockery of today’s X Factor-led ideas of entertainment, and remains a defiant and poignant reminder that there is amazing talent out there to be found. It’s been reported that a note by Ayers’ bedside after his death bore the legend “You can’t shine if you don’t burn!”, hinting that new music was possibly on the way. That ideas were still flowing. Kevin Ayers burned very bright in those 68 years on this planet, and his music still does. It remains something to be cherished.

This article originally appeared in issue 35 of Prog Magazine.

Writer and broadcaster Jerry Ewing is the Editor of Prog Magazine which he founded for Future Publishing in 2009. He grew up in Sydney and began his writing career in London for Metal Forces magazine in 1989. He has since written for Metal Hammer, Maxim, Vox, Stuff and Bizarre magazines, among others. He created and edited Classic Rock Magazine for Dennis Publishing in 1998 and is the author of a variety of books on both music and sport, including Wonderous Stories; A Journey Through The Landscape Of Progressive Rock.