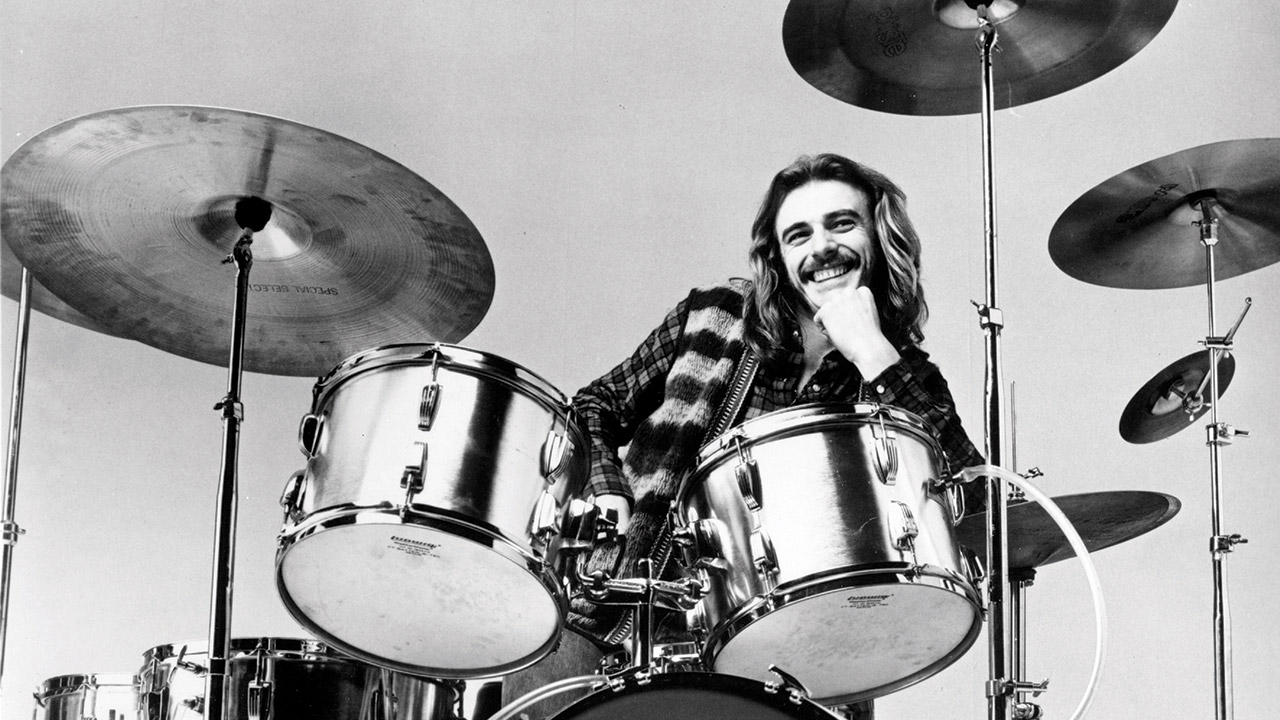

Our lives are so often accompanied by the music of chance. Attentive listeners will know that strange coincidences and unexpected encounters chime loudly throughout our personal histories, echoing and shaping our world with odd connections in ways that are unforeseen, fortuitous or simply surprising. For example, take Alan White. He was born in 1949 in the coal mining village of Pelton in north-east England. Not too far from that settlement is Drum Road, now the site of the Drum Business Park. Just a few miles from his Pelton birthplace sits the town of Washington. That, in turn, isn’t too far away from Newcastle, where White’s first band, The Downbeats, played its clubs and halls in the early 60s. Fast forward a couple of decades and White became a long-term resident of Newcastle in Seattle, USA. Originally one of the very first mining towns in the region, Newcastle lies in the state of Washington. This series of apparently disparate accidents of geography and their sense of one lifetime echoing with another must have brought a smile to his face.

Alan White had a habit of being the right guy in the right place at the right time. After stints in London playing in ex-Animal Alan Price’s group, White fell in with Griffin, like him a bunch of northerner ex-pats. One night John Lennon was in the audience. Though he didn’t know it at the time the trajectory of his life changed forever that night. It’s a story White told many times over the years of how, following the gig, he received a telephone call from someone claiming to be John Lennon. Initially he thought it was a prank but discovered it was real enough with the soon-to-be ex-Beatle inviting him to be in the band that would be appearing at the Toronto Rock And Roll Revival show the next day. Having only turned professional three years earlier at the age of 17, he now found himself rehearsing on the plane with Lennon, Yoko Ono, Klaus Voormann and Eric Clapton. Released by Plastic Ono Band, Live Peace In Toronto 1969, the resulting album, commingled rock’n’roll numbers and chugging blues riffs, the latter spattered with feedback and shock therapy vocals.

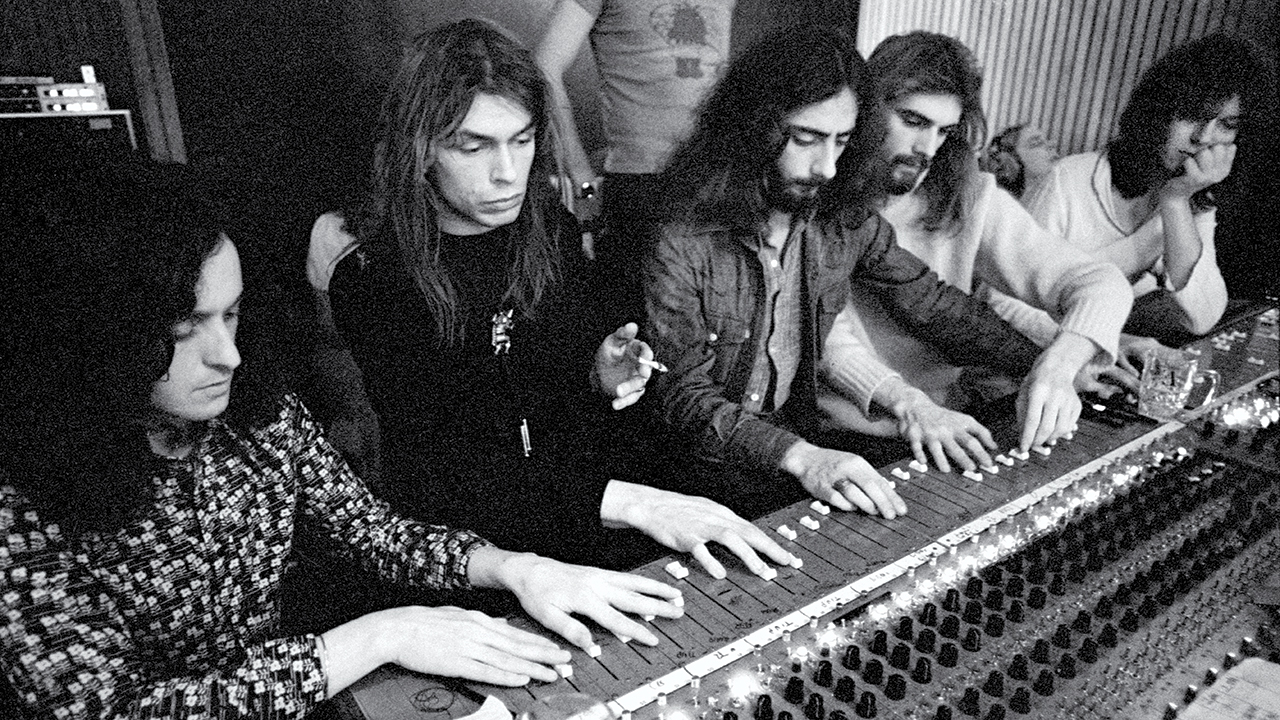

White’s easy-going demeanour and obvious abilities clearly resonated with Lennon, leading to an endorsement that relocated White in the swirl of musicians contributing to George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass in 1970. The following year he appeared on seven of the 10 tracks on Lennon’s Imagine. Not a bad calling card. Interestingly, whenever White told these stories they weren’t recounted in a boastful manner but rather with a smiling ‘how did I get here’ sense of wonderment, fully appreciating the chance and happenstance at play in his life. Similarly, after Bill Bruford abruptly quit Yes in 1972 following the completion of Close To The Edge, Yes needed a replacement fast. The right time and place on this occasion happened to be sharing a flat with Yes’ producer and engineer, Eddy Offord.

White had been in the studio during the making of Close To The Edge, occasionally playing drums with the others after Bruford had left for the day. He knew the band and they knew him so joining, though daunting, was a no-brainer for White. Daunting, because just like his appearance with Lennon in the Plastic Ono Band, the offer came with virtually no time to prepare.

That White met such a challenge and all the attendant pressures with such apparent equanimity says much about his skills and his character as a person. With just three days between the offer and the first gig, his assimilation, in short order of a setlist considerably more complex than the clutch of 12-bar blues he’d played in Toronto, has rightly entered the annals of Yes folklore. But there’s another quality that was crucial to his success in taking over the drum stool. He wasn’t just a quick learner with an ability to provide the beat with a sure-handed power. As a person, White came with a can-do attitude and a self-deprecating affability that stood him in good stead with Lennon and even a stint with Ginger Baker’s Air Force. His down-to-earth, even temperament meant that when it came to the next part of his already eyebrow-raising career, White was the calm centre in the whirl of anger management issues that were sometimes a feature of Yes’ rehearsals and recording sessions.

Having had piano lessons as a kid in the north-east and later learning his way around the guitar, he was also able to explain, clarify, and add compositional suggestions to the creative processes at work within Yes. During the recording of Tales From Topographic Oceans, White’s tinkering with a chord sequence on the guitar caught Jon Anderson’s attention, who added them to The Remembering (High The Memory). Similarly, during one of Rick Wakeman’s absences from Morgan Studios, the drummer was at the piano and wrote the sequence that would be used for the ‘Hold me my love’ bridge on Ritual. “Jon and Steve were credited for the album, but Chris and I wrote a lot of the parts on side four,” White told this scribe in 2016, adding: “It was a creation between all of us. Afterward, we worked out a publishing deal to reflect everyone’s contributions.”

The tribal loyalties of fans are infamous these days, with some quick to tell anyone in earshot why Yes with Bruford is better than Yes with White. Alan wouldn’t have cared about such chaff and chatter then and nor did he in the years that would follow. In 1999 Chris Squire remarked to journalist Chris Welch, “Out of the 30 years Yes has been together, Alan has been there for about 27 of them. People always say Yes had two drummers, but actually Bill was only there for four years.” Unflappable as ever, White simply got on with the job and made it indelibly his own.

Such was the artistic and commercial momentum of Yes in the mid-70s that each member released their own solo album. White’s contribution to a sequence that included Steve Howe’s Beginnings, Jon Anderson’s Olias Of Sunhillow, Chris Squire’s Fish Out Of Water and Patrick Moraz’s Story Of I, was Ramshackled. Significantly unvalued by fans and some critics at the time of its release in 1976, it was, in essence, a reunion of Griffin, the band John Lennon saw playing in 1969. A likeable mix of rootsy tunes, laid-back ambience and the occasional jazz-rock excursion, it remains underrated; its biggest crime, so it is often argued, is that with the exception of Spring-Song Of Innocence, which featured Anderson’s lead vocals and Howe on guitar, it didn’t resemble Yes. That kind of short-sighted thinking fails to meet the album on its own merits. It’s the sound of Alan enjoying himself. “I tried to get a lot of different kinds of music on the album because I like playing lots of different kinds of music,” he said upon its release. “Within Yes you can express your feelings of doing something nobody’s ever done, we’re always trying to see round the corner or over the hill, trying to take your particular instrument in a new direction… I just made an album of music I really enjoyed playing with a good band.”

In 2011 White was invited to collaborate on a project with bassist Tony Levin and guitarist David Torn. Their self-titled album was a blast of fresh air and full of surprises, not least from the drummer’s performance on the left-field material. The sense of liberation in the way he engages with the spiky tunes that are brimming with neatly executed twists and musical back-flips is tangible. His energy and power propels Torn’s unconventional scatter-gun sonics and meshes deep into Levin’s famous low-end grooves. Standing about as far away from Yes’ Fly From Here, released the same year, it’s a much-overlooked example of what White was capable of in a different creative context.

When considering his time in Yes during the 1970s and early 1980s, White radiated a quiet satisfaction, the hard edges of his hometown accent softened by so many years living in North America. Away from the what might be regarded as the classic era of the band, he expressed a fondness and appreciation for 91025, an album that he felt had kept the band moving forward at a time when the whole edifice of Yes looked like it was on the verge of collapse. Despite the various line-ups, reinventions, and disputes, White’s commitment to Yes and its achievements over the decades was tangible. “It was very exciting because the band was very vibrant and it’s good to have the memories and the fact that you made a great career of really adventurous music that was trying to move things in a good direction.” When he joined the band both sides agreed to give it a few months to see how things might work out. In the end, Alan White gave Yes 50 years of his life, a life well lived.

This article originally appeared in issue 131 of Prog Magazine.