Hollywood actor Bradley Cooper’s disembodied head is currently in a small village just outside Doncaster. Next to it stands a waxwork replica of his torso. The body parts belong to a US branch of Madame Tussauds and have been sent here, to a costumier’s in Yorkshire, to be measured for an outfit.

Stagewear Unlimited have been dressing showbiz stars for more than 40 years. Their client list has included Michael Jackson, Norman Wisdom, Cannon And Ball, geriatric DJ/stripper ‘Gyrating Jeff’ – and Saxon.

Another of its regular patrons, former Yes keyboard player and TV pundit Rick Wakeman, is here today, being fitted for a new outfit for a forthcoming performance of his 1975 extravaganza The Myths And Legends Of King Arthur And His Knights Of The Round Table.

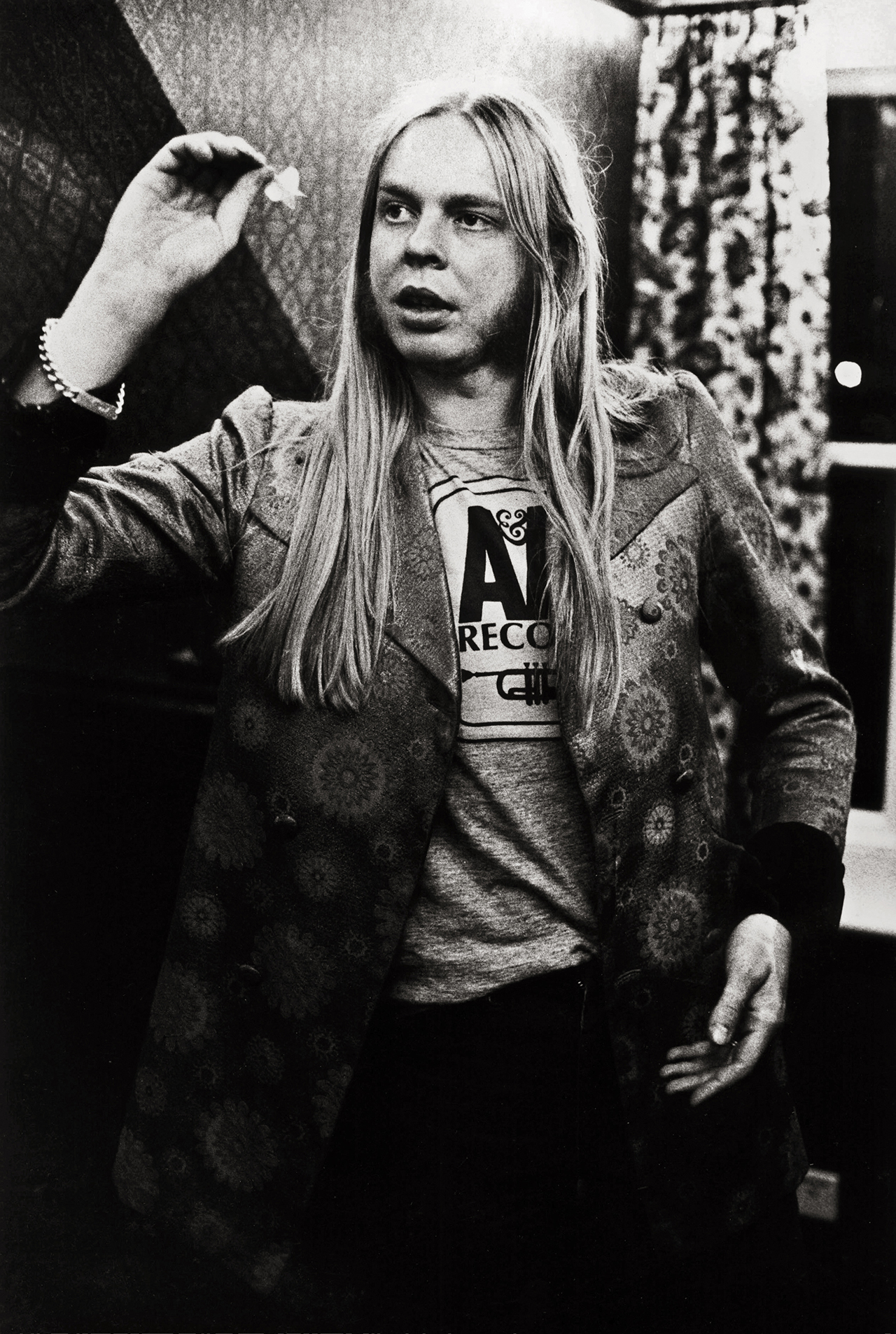

Stagewear Unlimited’s walls and ceilings are plastered with yellowing photos commemorating more than four decades of light entertainment. Wakeman, with his brightly striped jacket and long blond-white hair, fits right in. He has the repartee of a Working Men’s Club compere or after-dinner speaker (he’s off to Sheffield for a corporate gig later), and is surely the only member of the 70s rock aristocracy whose interview chat jumps from David Bowie to Frankie Vaughan; from Jon Anderson to Joe Pasquale.

But Wakeman looks, frankly, knackered. He’s currently producing the final scores for his 2016 remake of King Arthur, and planning its grand performance at the Stone Free Festival at London’s O2 Arena in June. Also in the works are more TV shows, more ‘corporates’ and a new album with former Yes men Jon Anderson and Trevor Rabin. You suspect the 66-year-old Wakeman will keep going until he can’t keep going any more.

Showbusiness is in Wakeman’s blood. He was born in May 1949 in Perivale, West London, to musical parents Cyril and Mildred. “Mum and Dad had been in a concert party before the war,” he says, settling into a comfy chair. “Dad played piano, Mum and Aunt Esther and Aunt Olive sang, Uncle Stan played the banjo and Uncle Laurie was a comedian. But the war wrecked all that.”

Cyril Wakeman gave it up and went to work for a building firm. But on Sunday nights the extended clan joined him and Mildred in the front room of their terraced house in Northolt to relive the old days. The five-year-old Rick would creep out of bed, and listen, mesmerised, as Uncle Stan did his George Formby routine and his mum and aunts sang the old music-hall number The Haddock, The Kipper And The Bloater.

Eventually the infant Rick was allowed to join in and play the family’s upright piano. “Everybody clapped, and I thought, I’ll have some more of that, and refused to go back to bed.” Wakeman was already hooked on “the joy of applause”. Later, aged 10, he went rogue at Wood End Junior School’s annual talent show by playing Russ Conway’s piano hit Side Saddle instead of his rehearsed piece, Clementi’s Sonatina. “And all the parents clapped.”

It was uphill or downhill from there, depending whether you were Rick or his piano teacher, Mrs Symes, who described her precocious pupil as gifted but undisciplined. “Which was a fair assessment,” he agrees. “I’d get fed up of learning what I was supposed to be learning – ‘Forget Grade Four, why can’t I just jump to Grade Eight?’ I’ve been like that my whole life.”

Wakeman’s headmaster predicted that his wayward charge would “end up in one of three places: 10 Downing Street, prison or on stage at the London Palladium”. Wakeman hoped for the latter, and played in trad jazz, blues and country and western groups, everywhere from church halls to strip clubs. He enrolled at the Royal College Of Music in 1968, but quit the following year because he was being offered so much session work.

“Mum was distraught, bless her,” he says. “There was always an element of that Ronnie Corbett sitcom Sorry with me and my mum. I was Timothy Lumsden, an only child, and she really did tell me to make sure I wore clean underwear in case I got knocked over.”

It was a difficult time for the Wakemans. For a fortnight after her son left college, Mildred avoided Chatterton’s butchers in Northolt, where she often met up with other local mothers. “But then I played on Bowie’s Space Oddity, it was a hit, and she was in there like a shot,” he laughs: ‘Oh, my Richard played on that…’ She was a great proud mum.

“David Bowie was the biggest influence and encouragement I could ever have wished for,” Wakeman said, shortly after Bowie’s death. Just this week he learned that his piano rendition of Life On Mars (he played on the 1971 original), released to raise money for the Macmillan cancer charity, had reached No.1 on the Physical Singles Chart.

“I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t chuffed to old boots,” he admits. “These days there’s a chart for everything, though – Very Old Prog Rocker Plays Piano Chart. But it’s great. And also bloody typical that the one time I have a number one single I don’t earn out of it. But that’s the story of my life.”

Wakeman claims two record companies have since asked him to make an album of Bowie covers, but he refused. “I did Life On Mars on Simon Mayo’s Radio 2 show, and thousands of people contacted the BBC and suggested I put it out for a cancer charity. It was for a good cause. I played on Space Oddity and Life On Mars and Hunky Dory. But I don’t want it to look like I’m cashing in.”

Rick’s other ‘hits’ in the late 60s and early 70s included Cat Stevens’s Morning Has Broken and T.Rex’s Get It On. In 1970 he joined folk rockers The Strawbs. One day he got a phone call from prog rock pioneers Yes, and on the same day one from Bowie. Apparently it was a toss-up between joining Yes or Bowie’s new group the Spiders From Mars. He chose Yes, because he wanted to write his own music. “I often wonder what might have been.”

Wakeman made his Yes debut on their 1971 album Fragile, before unleashing his growing arsenal of keyboards on 1972’s Close To The Edge and the following year’s Tales From Topographic Oceans.

At a show in Connecticut, he took a shine to the gig compere’s flamboyant cape and gave him 200 dollars for it. Like Tommy Cooper and his fez, Wakeman had found his trademark gimmick. Rick in his shiny cloak became a fixture on the front page of Melody Maker. He brought humour and showbiz flair to Yes’s knotty prog rock – or tried to. “Yes was a straight-faced band and Rick wasn’t,” Yes’s guitarist Steve Howe said in 1974.

Wakeman’s well-travelled anecdotes about Yes present him as the boozy, meat-eating joker tirelessly teasing his spiritually-minded, vegetarian bandmates. The story of him eating a curry on stage at Manchester’s Free Trade Hall has done the rounds forever. But there was also the time he asked Yes’s on-tour chef to cook a roast turkey dinner for him. Wakeman later recalled how each of his bandmates, apart from the unbreakable Howe, approached him afterwards to ask for turkey leftovers, but insisted he didn’t tell the others.

Wakeman pokes fun at Yes’s grandiosity, but sounds a bit wistful for those days. “This might be a terrible analogy, but Yes’s music reminds me of Fawlty Towers or Father Ted – the prog rock of comedy,” he offers. “Each time you watch those shows or listen to those albums you spot something you missed before and go: ‘Oh, that’s clever.’”

Like a traditional comic mourning the death of clubland, you have a hunch Wakeman thinks music was better in the 70s. “It was a period when people wanted something more than just pop,” he says. “Nothing wrong with pop, but Yes was music you could really immerse yourself in.

“When it worked, it really worked. Fragile, Close To The Edge and Going For The One are the three best Yes albums. Because we were all bringing music that was perfectly suited to Yes – and no good for anything else,” he says with a laugh.

That said, Yes were a bit much for the Northolt mothers. “My mum didn’t get it at all. Close To The Edge? ‘Ooh, it’s a bit long, dear.’ My dad got it. But he said: ‘I can see what you’re trying to do, son… But I’ve no idea how you’re going to get there.’”

But Wakeman was soon thinking beyond Yes. His second solo album, The Six Wives Of Henry VIII, went Top 10 in 1973; Journey To The Centre Of The Earth, his lavish interpretation of Jules Verne’s sci-fi novel, reached No.1 the following summer. These days no BBC4 documentary about the ‘golden age of rock’ is complete without a clip of Wakeman in his cape, eyes closed, working his Doctor Who-style keyboard console while an orchestra parps away behind him.

For Wakeman, though, it had to be the London Symphony Orchestra. Just like it had to be biggest inflatable dinosaurs in the lake in front of the stage for his summer ’74 performance of Journey at Crystal Palace Bowl. One of the monsters sprung a leak, and “farted its way through the entire performance”, as if to confirm the increasingly windy nature of some prog rock.

Then it all started to go wrong. The day after playing Crystal Palace, Wakeman was rushed to hospital. He’d had not one but two heart attacks. “I was twenty-five years old,” he says, “which was ridiculously young.”

It was cigarettes, booze and overworking that did it. A pattern was already developing. Wakeman’s current workaholism makes sense when you learn that he wrote some of his 1975 album The Myths And Legends Of King Arthur while recuperating in hospital. His dad’s earlier assessment – “I can see what you’re trying to do, son… But I’ve no idea how you’re going to get there” – could also have applied to Wakeman’s infamous performance of Arthur on ice at London’s Wembley Arena. With its DIY castle and pantomime horses, it’s now regarded as the ultimate 70s rock folly. Wakeman sees the humour in it, but he adores the music. “We’re re-recording King Arthur now,” he reveals, “and it’s been funded by [online direct-to-fan music platform] PledgeMusic. Cos otherwise it would have cost us a bloody fortune.”

The interactive nature of the project has been a revelation to him. “You get feedback,” he marvels, “and people are not shy. ‘Can I come to a rehearsal?’ ‘Can you do the vocal version of Merlin The Magician?’ It’s like buying a ticket for a football match and getting to go in the players’ lounge as well. People expect more for their money, and if they don’t like it they will let you know.”

Wakeman quit Yes the first time in 1974, because he thought they were disappearing up their own fundament with the impenetrable concept album Tales From Topographic Oceans. At the time, Yes were huge. He could have stuck it out and become a millionaire. In 1979 he quit Yes a second time, only to see them enjoy their biggest hit ever with 1983’s Owner Of A Lonely Heart. But, like his refusal to cash in with an album of Bowie covers, Wakeman walked away because the music didn’t feel right. “Yes had all stopped singing from the same hymn sheet.

“This is why David Bowie was so good,” he stresses. “When I first put together my own band [the English Rock Ensemble in the mid-70s] I didn’t just take a leaf, I took… the whole tree out of David’s book. David knew what he wanted, but he let his musicians be themselves.”

Wakeman’s belief in the music above all else has sometimes been his undoing. He remortgaged his house to help fund Journey To The Centre Of The Earth in the 70s, then lost “a small fortune” on the subsequent US tour. By 1977, punk and new wave were in vogue, Wakeman’s album sales were dwindling, and his extravagant spending left him £350,000 in the hole at the end of an undersold tour. Something had to change.

The 1980s were a funny old time for Rick Wakeman. His music was desperately unfashionable, and his Orwellian concept album 1984 was his last to make the Top 40.

Bankruptcy loomed, but he stayed solvent by writing soundtracks for TV documentaries and straight-to-VHS films. He also moved to the Isle of Man, where he set up a studio, recorded new age music and befriended comedian/actor Norman Wisdom, who apparently “swore like a trooper and told the most disgusting jokes”.

It was also during the 80s that Wakeman made his first TV show. In 1982, rock fans found their usual choice of Top Of The Pops or The Old Grey Whistle Test added to by Channel 4’s Gastank, a haphazard mix of music and chat in which Wakeman played keyboards and interviewed boozy pals such as John Entwistle and Phil Lynott. It lasted one series, mainly because the station complained that “there were too many old rockers on it”.

But TV has sometimes been Wakeman’s salvation in between erratic solo ventures and his on-off relationship with Yes. His easy manner and way with a good yarn made him a comfortable fit for chat shows, quiz shows, any show, really. “I love doing TV,” he says with a grin. “Countdown, Watchdog, Pointless Celebrities, done ’em all – great fun.”

His ‘talking head’ appearances on BBC’s Grumpy Old Men in the 2000s made him a household name in households that had never owned a Yes album. “Usually when I do a ‘corporate’ I get introduced as a grumpy old man rather than the bloke from Yes. But that’s fine.”

These days his musical career is handled by Yes’s veteran ex-manager Brian Lane, and his corporate engagements by his agent, one-time TV ventriloquist Roger De Courcey of Nookie Bear fame. Wakeman seems comfortable in both worlds.

Although he still talks like he’s propping up the bar of a Home Counties boozer with real ale on tap and a horseshoe over the door, he’s now teetotal. “I stopped smoking in seventy-nine and drinking in eighty-five,” he says. “I didn’t have any choice in the matter. I was going to die otherwise. My only saving grace is I never took drugs. I knew that if I smoked even a bit of grass it would only end one way. It goes back to what I said earlier – ‘Forget Grade Four, why can’t I just jump to Grade Eight?’”

How bad did it get? “When I smoked I smoked eighty a day, when I drank it was a whole bottle of port or brandy…” His voice trails off. “I have an excessive personality. Cars? Can’t have one, had to have twenty-two. Keyboards? Can’t have two, had to have twenty-two. Wives? I’ve had four.”

Wakeman had been through two marriages before tying the knot with his third wife, former Sun Page 3 girl Nina Carter, in 1984. Their marriage lasted until 2004. He’s been married to freelance writer Rachel Kaufman since 2011, and the couple now live in an old millhouse in Norfolk. “And yes, she does get on my case about working too much,” he says quietly.

His excessive traits also spread to Yes – the band he’s left five times. After quitting for the fourth time, in 1998, Wakeman began another solo project, Return To The Centre Of The Earth. But the workload proved too much – again. “My medical history ain’t great,” he deadpans. “I don’t have things like in-growing toenails, I have things like being told I have forty-eight hours to live.” Wakeman was in his studio on the Isle of Man when the problems began. “I had a deadline to meet. I’d had a month of working all day, falling asleep, waking up at the desk, eating a bowl of soup and starting all over again.”

In the middle of all this he flew to Los Angeles to oversee Star Trek actor Patrick Stewart’s narration on the album: “I felt ill on the plane. Patrick did his recording, and then I flew back, no sleep, and felt even worse. I got home Friday night and went to bed.”

Realising he needed a break, Wakeman took the Saturday off to play golf. “I don’t remember much after arriving at the club,” he winces, “only being stretchered into the ambulance and thinking: ‘I don’t like this. I can’t breathe.’”

He was diagnosed with several critical ailments, including double pneumonia and pleurisy. He was put into an induced coma. When he woke up it was Tuesday. “They’d stuck an oxygen mask on me, so I had some idea where I was. But I looked at the end of the bed and five of my kids were there.” That surprised him, as his eldest sons lived in England and their younger half-brother in Switzerland. “I remember thinking: ‘Fuck! I must be ill.’”

Wakeman’s eldest son, Oliver, later revealed that they’d all had calls from the hospital. “Basically saying: ‘Come now, because your father might not make the week.’”

Rick shrugs. “But I did. And I’m still here.”

It seems Wakeman has been cramming as much as he can into his life since that narrow escape. He recently came to the end of his second year as King Rat of The Grand Order Of Water Rats, a charitable fraternity of musicians, actors and sportsmen. “It’s the oldest entertainment order in the world,” he explains. “It’s been going 127 years. But you can’t say: ‘I want to be a Water Rat,’ you have to be invited.”

Wakeman received an initial approach after he’d played a solo show in Hemel Hempstead in the late 80s. “There was a knock on the dressing-room door and it was Frankie Vaughan,” he recalls with a chuckle. The old song-and-dance man of Give Me The Moonlight Give Me The Girl fame was not Wakeman’s target demographic. “I said: ‘I wouldn’t have thought this was your cup of tea, Frankie’.’”

It wasn’t. But Vaughan invited Wakeman for lunch. It was the beginning of a lengthy vetting process. After their third date, Vaughan asked whether Rick was interested in joining the Order. He told them he was. “And four years later I received a letter of invitation. I was initiated on the same day as Joe Pasquale.”

Previously, the Order had been rather light on rock musicians. Less so now. “Brian May’s a Rat,” says Wakeman. “So is Gordon Giltrap. And Nicko McBrain. Nicko’s a very proud Rat.”

But after two years as King Rat, Wakeman declined a third term. The workload was too much. Will he ever slow down, you wonder?

“I am aware that I am going to be sixty-seven this year. And it feels like it sometimes,” he says, pulling a pained expression. “But I’m still up at the crack of dawn and I work every day. I took four days off earlier this year, and that’s the first holiday Rachel and I have had in eight years. She’s still wondering when we’re going to have our honeymoon.”

Not any time soon, if Rick’s diary is anything to go by. He’s currently emailing music back and forth with Jon Anderson and Trevor Rabin (“When my engineer heard it he immediately said: ‘That sounds like Yes’”). The trio are due to tour soon with an as-yet unnamed drummer. Before then, though, there are orchestral scores to be finished for the King Arthur show. Wakeman is bracing himself for 18-hour working days, but promises he’ll remember to sleep and eat this time.

“If I’m brutally honest, that’s when I’m at my happiest – on stage,” he says. “Walking out there knowing all the pieces of the jigsaw are in place, and you can finally see the big picture.” He looks knackered, but happy.

Surrounded by photographs of singers, actors, comedians and one Hollywood hearthrob’s disembodied head, Rick Wakeman couldn’t be in better company. As he drives off to Sheffield for that after-dinner engagement, it’s clear he lives for that old truism: the show must go on. After all, it’s in his blood.

SUITS YOU, SIR

Stagewear Unlimited: threads makers to the stars.

Neil Crossland has been in showbusiness since the age of seven. He toured in groups in the 60s before forming Stagewear Unlimited in 1975. Crossland spotted a gap in the market – and decided to fill it.

“When I was playing the clubs there was nowhere to get outfits made,” he says. “You’d see a jacket you liked in a shop, but they’d only have one or two of them – and if you’re playing in a group you might need four or five.”

Crossland and his “team of ladies” manufacture their bespoke outfits in Stagewear’s HQ in a converted church hall in a village near Doncaster in Yorkshire. They don’t advertise – they don’t need to, their reputation has spread by word of mouth, from the northern club circuit to comedians and game-show hosts in the 70s and 80s (Little And Large, The Grumbleweeds, Charlie Williams, Jimmy Cricket), to pop stars, including Michael Jackson and Oasis, and corporate clients including ITV, P&O Ferries and Warner holiday camps.

Rick Wakeman discovered Stagewear Unlimited 20 years ago, through former Coronation Street actor Johnny Leeze. “Rick liked Johnny’s jacket and he passed my number on,” Crossland explains.

Wakeman had been booked to host the TV comedy show Live From Jongleur’s, and needed a different jacket for every show. Since then Stagewear Unlimited have met most of his sartorial needs. “He reckons I’ve made him eighty-two jackets and half-a-dozen capes,” says Crossland. Is Rick a difficult customer? “Not at all,” he says, laughing. “The great thing about Rick Wakeman is any stupid jacket, he’ll wear it. Rick will wear anything.”