With their second album, Rising, Ritchie Blackmore’s post-Purple band Rainbow created one of rock music's defining records. Here, the man in black and his former bandmates look back on the tensions that fuelled this landmark album – and broke the band apart.

Tokyo, December 16, 1976

In the dark, smoke-filled basement disco of the Tokyo Hilton, the night is in full swing. The music throbs with a mid-tempo pulse, as salary men with open collars, loosened ties and uncomfortable paunches knock back the sake. Refined-looking and impeccably dressed hostesses hover in the background, circling their prey with casual yet purposeful intent.

In one corner of the room, I can just about make out the blurry outline of someone who seems out of place in this den of iniquity. Ritchie Blackmore, guitarist and driving force with Rainbow, sits almost hidden in an anonymous alcove. Dressed in his trademark black, only the whites of his eyes and a half-pint glass of imported German beer are visible. Exhausted after two shows with his band Rainbow at Tokyo’s famed Budokan theatre, Blackmore relaxes with one foot on the table, displaying a custom-made boot from Kensington Market, where Freddie Mercury once worked a stall. Tapping a finger on his cheek, he aims his laser stare at the girls dancing around the DJ booth. This isn’t purely carnal; Blackmore has been known to take bandmates to clubs like this, instructing them to observe which rhythms make the punters dance.

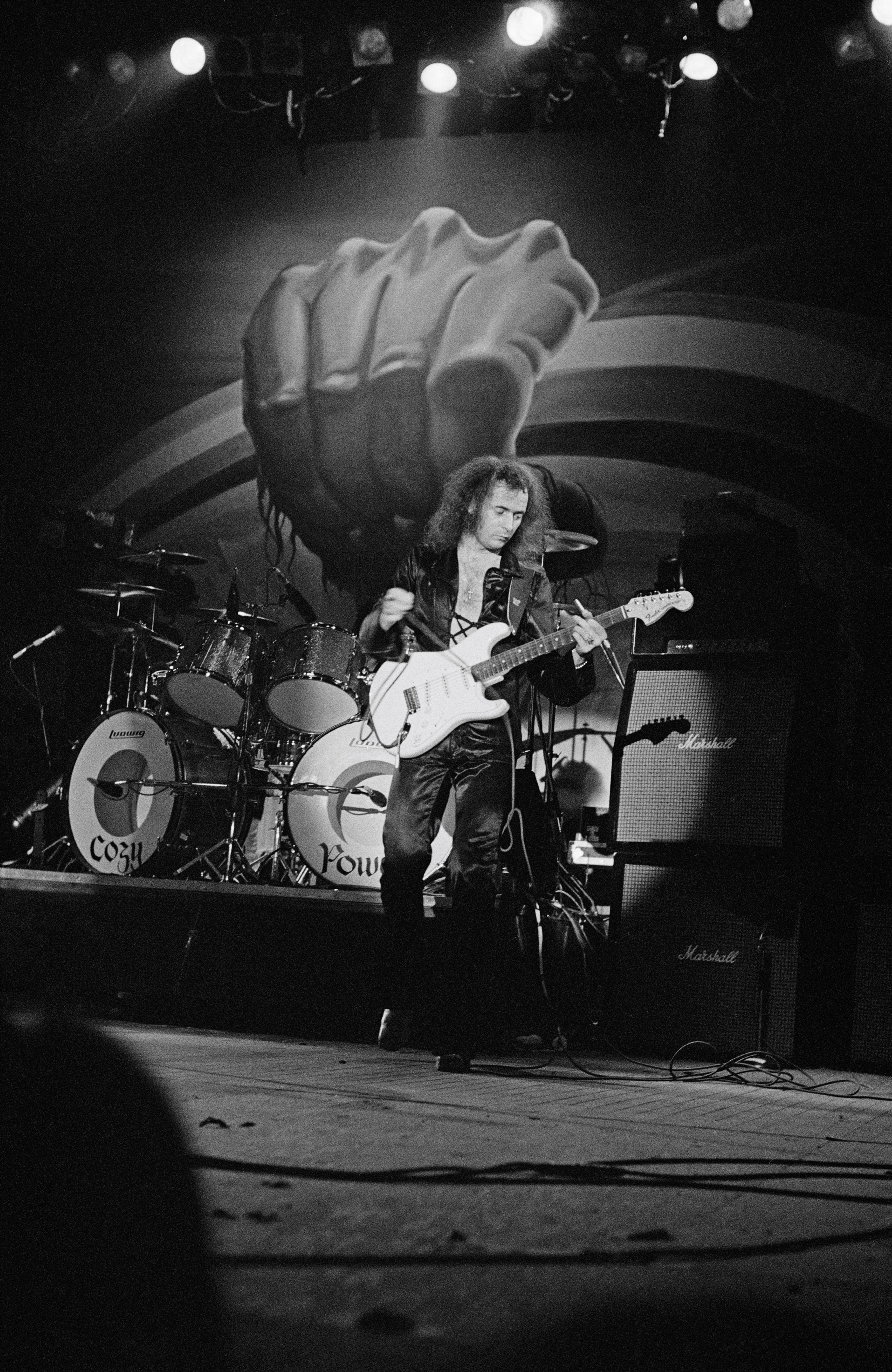

Rainbow have just completed an arduous, six-month world tour in support of their second album, Rising. The band – Blackmore, vocalist Ronnie James Dio, bassist Jimmy Bain, keyboard player Tony Carey and drummer Cozy Powell – are out to enjoy themselves. Blackmore, though, has other things on his mind.

“Here you go, take Jimmy out on the town,” says Ritchie, handing me a wad of yen. “He’s a lovely guy. Go out and have some fun.” As Bain and I head off to the bustling nightlife of the Roppongi district, Blackmore is already thinking about making changes to a band that, on the surface, seems to be perfect. Bain is set to be the first victim of his axe, and the guitarist – who by all accounts is still fond of the bassist today – wants to soften the blow.

Even by the standards of the 70s, the story of Rainbow’s classic second album – and its messy aftermath – is a tangle of creative genius, colourful characters and personal tensions. Rising captured the band at their peak. Driven by the guitarist’s single-minded vision, it pioneered an epic sound whose influence can still be heard today. In the space of 18 months, Blackmore had assembled one of the greatest rock bands ever – and then dismantled it.

North West London, September 1975

It was in the early hours of the morning when the phone rang in Jimmy Bain’s flat. No doubt bleary-eyed after a late-night session at his favourite haunt [the now defunct Speakeasy] the bassist stumbled blindly in the dark, cursing the gremlins who had moved the furniture, and wishing he had topped up the electricity meter. On the other end of the phone was a guitar-tech friend and fellow Scot named Fergie.

“I’m in Los Angeles working with Blackmore, man,” Fergie rasped above the pre-digital transatlantic hiss. “He’s looking for a new bass player, and I’ve put your name forward.”

Blackmore had left Deep Purple following 1974’s Stormbringer album, tired of the band’s relentless recording and touring schedules, growing funk-rock influences and, ultimately, their refusal to record a cover of Black Sheep Of The Family by cult trio Quatermass. Blackmore realised he was losing his grip on the band he formed, and quit to put together Rainbow with members of US rockers Elf, a former Deep Purple support band fronted by singer Ronnie James Dio. And now Blackmore was tapping up Jimmy Bain.

When Bain put the phone down, a million thoughts raced through his head. “I’m half asleep, thinking this is a bad joke,” Bain recalls today, laughing, “then all of a sudden, I’m talking to Blackmore – and he was one of my idols.”

Now aged 63 and living in the LA suburb of Eagle Rock, Bain these days is an amiable man, with a CV that features stints with Dio, John Cale and Ian Hunter. In 1975 he was fronting Harlot, whose drummer, Ricky Munro, had played with Blackmore in Mandrake Root in the 60s. Bain was a confirmed partier, whose lifestyle would eventually lead to drug and alcohol problems [now successfully conquered].

Harlot had a Sunday night residency at the Marquee in Wardour Street. Blackmore insisted he would fly over from Los Angeles to check them out. Sure enough, the following Sunday Bain dropped into The Ship, a pub close to the Marquee. Standing at the bar, with a pint and chatting to friends, was Blackmore.

“I nearly shit myself,” says Bain. “He’s not only come all the way from LA, he’s got his manager and Ronnie James Dio with him. I thought: ‘All I’ve got to do now is play a great show’.”

Not everyone in Harlot was quite so on the ball. Ricky Munro, as a former bandmate of Blackmore, assumed the presence of the guitarist meant he might be up for the Rainbow gig, and opted to seek courage in several pints of Guinness. By show time the drummer was in no fit state to perform.

“So I’m out front singing, playing bass and generally flying around the stage,” recalls Bain. “I look round and there’s puke all over the place, on the floor toms, it’s all over me. And I thought: ‘Oh no. This is not going well’.”

After Harlot had muddled through their set, Bain skulked off to the dressing room, smashed his bass against a wall and downed several Jack Daniel’s. The door opened, and Blackmore stood in front of him. Bain steeled himself to face the music.

“Before I could apologise, Ritchie said: ‘The band made you look great,’” he says now, still astounded by the verdict. Bain was in.

Within a fortnight the bassist had flown to LA to hook up with the rest of the band. But in a portent of what was to come, changes were afoot. Blackmore had recorded Rainbow’s self-titled 1975 debut album with the members of Elf. But, with the exception of Dio, the guitarist had no intention of retaining a group he felt had the charisma of a bar band. Bassist Craig Gruber was the first to go. Drummer Gary Driscoll was jettisoned a few days after Bain arrived in LA. He was soon followed by keyboard player Mickey Lee Soule.

As painful as it was to see his former bandmates jettisoned, Ronnie James Dio shared Blackmore’s musical vision. “Line-up changes and more commitment to why Ritchie and I started the band together made for a different direction,” the singer later explained. A calm, composed presence, Dio counterbalanced Blackmore’s more emotional and occasionally volatile behaviour. “When you’ve spent years touring shitty, chicken-in-a-basket circuits where you have to confront some pretty scary characters to get your paltry wages, you quickly learn not to take any crap,” he explained.

The trio of Blackmore, Dio and Bain began auditioning drummers at Hollywood’s Pirate Sound studio. The procedure gave Bain an insight into the guitarist’s dark sense of humour.

“The guy would come in, set up his kit, and we’d go to the other side of the building and play pool,” the bassist recalls. “When he got comfortable, Ritchie would start this really fast riff: dat-dat-dat-dat-dat-dat… I’d join in on bass, and the drummer would start playing along. That would be great for five minutes. After 20 minutes the guy would be falling apart. Ritchie and me would stop playing and go back to the pool table without saying a word. We did this about 14 times and nobody even came close. And then Cozy arrived.”

Born in Cirencester, Cozy Powell had been playing drums since the age of 12. By 1975 his CV included a stint with Jeff Beck (one of Blackmore’s favourite guitarists), as well as hit solo singles Dance With The Devil and, prophetically, The Man In Black. He arrived at the studio from the airport, carrying his trademark over-sized drumsticks.

“Ritchie goes into his dat-dat-dat-dat-dat-dat… routine,” says Bain. “We do this for about 45 minutes and the tempo doesn’t fluctuate. We finish that, and before we could say anything Cozy starts another beat on the double bass drum. We were trying to fuck him up, and he turns it around on us. He was in.”

Last in place was keyboardist Tony Carey. The 22-year-old Californian was recording with his band, Blessing, at nearby SIR studios. Bain was introduced by his flatmate from London, who was working with Led Zeppelin in the studio next door. Bain convinced Carey to audition, And the keyboardist gave Blackmore a run for his money. “Tony played some Bach,” says Bain. “He could trade off with Ritchie note for note. So Ritchie hated him.”

Carey’s youth and naivety made him a target for Blackmore. “If Ritchie didn’t like someone in the band he would play terrible practical jokes on them,” Cozy Powell later recalled. “And he hated keyboard players.”

“I can’t remember a single sentence that Ritchie ever said to me that wasn’t sarcastic or condescending,” Carey says today. “There’s a snarkiness I’ve noticed from people born during the war – it’s resentment, because they’ve seen harder times. In me he found someone who didn’t give a shit. I’ll play as loud as you want and look you in the eye when I’m doing it.”

Despite the friction, as well as competition from former Curved Air/Roxy Music man Eddie Jobson, among others, Carey’s talent won out over his youth. He was Rainbow’s new keyboard player.

Munich, Germany, February 1976

Three months after Jimmy Bain joined Rainbow, the band flew to Munich’s Musicland studios to begin work on what would become Rising. The new line-up had already been broken-in with US dates the previous November, on which they unveiled three new songs: Do You Close Your Eyes, Stargazer and A Light In The Black.

“We had written Stargazer at rehearsals, and Tarot Woman, I believe,” Blackmore recalls today. “The other songs we made up in the studio, as far as I remember. We chose the studios because I worked there before. I like to be in Germany when I’m recording.”

Founded by disco producer Giorgio Moroder, Musicland had already hosted Led Zeppelin and The Rolling Stones, as well as Deep Purple and a Blackmore solo session. Technically and aesthetically, though, it left a lot to be desired. “We couldn’t get the drums to sound live enough, because it was an archetypal 70s studio with rugs on the wall”, Carey remembers. “So we got a wrecking crew together, hacked up the stairwell and turned it into a concrete tomb. That’s how Cozy got his sound.”

Overseeing the sessions was Deep Purple producer Martin Birch. Having worked with Blackmore’s former band during their most turbulent periods, the Zen-like Birch was a calming influence. He was also a black belt in karate, which gave him an assurance that came in useful when dealing with strong personalities.

Also on hand was Musicland’s resident engineer, Reinhold Mack. Apparently the German-born Mack would alleviate tensions by arriving in the studio dressed in a storm trooper’s uniform and barking out orders to the band. “I did this only once,” says Mack. “Ritchie always asked me about WWII stuff – as if I would know. So me and my assistant rented the gear and stormed into the control room cussing and shouting, almost scaring Ritchie to death. Fairly good acting on my part.”

- Ritchie Blackmore's Rainbow - live review

- Rainbow Rising: How Rainbow Became Accidental Pop Stars

- Watch Ritchie Blackmore’s Rainbow perform Perfect Strangers

- Rainbow reunion shows set for home release

Despite the underlying tensions, Rising is the sound of a band on fire. Recorded in the days before digital edits, the album has the intensity of a band getting it right in just a couple of takes, driven by Blackmore’s intense desire to prove a point to his former Purple bandmates. And then there’s the voice. “Ronnie was not only a talented singer, he was an amazing songwriter,” says Carey. “Even on the throwaway songs, which would be Run With The Wolf and Do You Close Your Eyes, he was ferocious. All five-foot-two of him.”

The album kicks off with the keyboard crescendo of Tarot Woman. “I especially like the Minimoog solo Tony does on Tarot Woman,” says Blackmore. “It was the first solo he did for the song. He said he could do much better, and went back and played for about an hour, but it never compared to the first solo.”

The album’s centrepiece is Stargazer, a nine- minute epic that combines Blackmore’s love of classical music with Dio’s vivid, fantastical lyrics. The track is built around a cello-inspired main riff, but the highlight is Blackmore’s uninhibited lead playing and searing slide work (a recent addition to his repertoire). The sweeping, Eastern scales add to the grandiosity.

“It’s amazing how many guitarists use the same old lines,” says Blackmore. “They never dare touch Arabic or Turkish scales.” For added grandeur, Blackmore brought in the Munich Symphony Orchestra, led by conductor Rainer Pietsch. But not everything went to plan.

“The orchestra was too flowery, and there was too much detracting from the simple melody,” Blackmore says in retrospect. ”We kept taking out parts, and I felt sorry for Rainer because he was so proud of this grandiose piece he had written. We got down to the bare bones, and mixed in some Mellotron to even out the orchestra not sounding cohesive or in tune.”

Rising was released on May 17, 1976. Although it has a running time of just 33 minutes and 28 seconds, Blackmore obviously felt it was complete, as he held back songs, notably Kill The King and Long Live Rock’N’Roll, for Rainbow’s next album. Looking back at Rising, opinions differ. Bain remains positive. “You could tell how much fun we were having,” he says. “It’s got that attitude.”

Blackmore, though, is more circumspect: “Although I thought the overall sound of the record was very punchy, it lacked warmth and bass. It was very ‘toppy’.”

Europe, Australia and Japan, June-December 1976

That summer, Rainbow embarked on a world tour that took them to four continents in six months. Surprisingly, their set didn’t include Tarot Woman and A Light In The Black, while Stargazer was rarely included. “For some reason the tempo for Tarot Woman didn’t translate for the stage,” Blackmore explains. “Same with Stargazer. Which was a pity.”

The tour was far from perfect. On the technical side, the vast, 40-foot wide Rainbow backdrop, powered by 3,000 light-bulbs, played havoc with the guitars and amplification. It was eventually chucked into the Atlantic at the end of the tour, to the delight of the beleaguered lighting crew.

By the time I joined the band to cover them for Sounds magazine, cracks were beginning to show. On the flight from Australia to Japan, Blackmore’s personal assistant, Ian Broad, got into a fight with Cozy Powell’s wife; Bain was ‘refreshed’ thanks to a prescription of Mandrax; Blackmore threw buns at disgruntled First Class passengers’ heads, and convinced confused staff that he was oblivious to events, while furtively fingering an innocent member of the group.

Bad news greeted the band when they landed: Tommy Bolin had died. Despite the fact that he had replaced Blackmore in Deep Purple, Blackmore was a fan of Bolin; Bain was a personal friend.

Against this chaotic backdrop, Rainbow had split into separate camps. Bain and Carey’s up-all- night lifestyle earned them the nickname the Glimmer Twins. Blackmore kept himself sane by indulging in his usual pranks, and swigs of his beloved Johnny Walker Black Label whisky prior to shows. The more sedate Dio, meanwhile, spent a lot of time in his room. Powell kept his head down and socialised with everyone. Despite the growing divisions, the band played some of their best shows of the tour, as captured on their 1977 live album On Stage.

Unknown to Bain and Carey, their cards had been marked. Carey had already been fired and rehired twice. The first time was before the band’s first US tour, when the band had unsuccessfully tried out Vanilla Fudge’s Mark Stein and Italian hotshot Joe Vescovi in his place. “The management sent Ronnie and Colin [Hart, Rainbow’s tour manager] to get me back to rehearsals,” Carey says. “Ritchie didn’t have the balls to do that. When I got there they had a tape of the Italian guy playing. It was garbage. So I got behind some keyboards. Ronnie looked over and grinned, then Ritchie grinned; nothing was ever said.”

The second occasion was on the last date of their British tour, on September 14, 1977 at Newcastle City Hall. During the fifth number, Blackmore suddenly walked over to Carey and told him to leave. The keyboard player did just that. The band finished the show as a quartet. “I guess he changed his mind because I stayed,” Carey reflects. “Fuck ’em. I knew I was good and they couldn’t find anybody to outplay me.”

“He was a good keyboard player,” Cozy Powell later said of Carey. “But he was also a little bit cocky, and if you got like that with Ritchie you were shot down in flames.”

Bain was shocked when he went to the band’s office to get details of recording sessions for the next album, only to be informed that his services were no longer required.

“I heard they were talking about getting rid of me during the Australian tour,” he says now. ”Maybe they thought I was drinking too much. It never affected my playing. I know it got wild and wacky in Japan, but we had been working our asses off for a year, we were winding down.”

In January 1977, a curt statement was issued to say that Carey and Bain had been dismissed. “They were not complementing the founder members’ style of playing and their musical direction,” ran the official line. Blackmore declines to say why he decided to part company with the two musicians.

Thirty-five years on, the bassist still sounds disappointed. “We could have grown together. It was a really good line-up”, he says. “We had fun when we played, and we got big crowds.”

March 2011

Asked when he last listened to Rising, Ritchie Blackmore replies: “I haven’t heard it in 25 years.” He continued to fly the Rainbow flag until 1984, albeit in increasingly radio-friendly forms.

“He was perturbed that he wasn’t being played on the radio,” reckons Bain, “and he decided to go a different route. He didn’t think we were going to get successful, because Rising was too heavy.”

After Deep Purple’s reunion in the 80s and a brief resurrection of the Rainbow name in the mid-90s, Blackmore has largely turned his back on rock in favour of his Renaissance-era project Blackmore’s Night with his wife, vocalist Candice Night. They have released 14 albums in as many years.

Ronnie James Dio left Rainbow after 1978’s Long Live Rock’N’Roll, while Cozy Powell stayed until 1980. Sadly, neither are around to celebrate the 35th anniversary of Rising in May: Powell died in a car crash on April 5, 1998; Dio succumbed to stomach cancer on May 16, 2010.

“Rainbow was such a great influence on younger musicians,” Dio said. “I’d see these bands who would say, ‘Rainbow were the reason I started to play.’ It was a ground-breaking time.”

Now aged 57 and living in Germany, Tony Carey has had a successful career as a performer, arranger and producer since leaving Rainbow. Two years ago he teamed up with Blackmore’s son, Jurgen, to form Over The Rainbow, performing classic Rainbow covers. Soon after, he was diagnosed with cancer and given only a 10 per cent of survival. Remarkably, he beat the disease and is now fit and about to take Over The Rainbow out on the road again. “I’ve lost many of my organs but managed to save my Hammond,” he jokes.

After Rainbow, Jimmy Bain joined Dio in the singer’s solo band. Today he’s threatening to release a solo album, and has started writing an autobiography, called I Fell Into Metal. Despite past tensions he has kept in touch with Blackmore, and says he has no bad feelings towards his former boss: “I was kind of pissed off that I didn’t get to stay longer, but I can never say anything bad about Rainbow. I was only in it for two years, but it’s done me a lot of favours.”

A recent two-disc, expanded reissue of Rising saw the original widely praised as one of the defining albums of the 1970s; the group who recorded it have been hailed as one of the most under-appreciated rock bands ever. Even as far back as 1976, Ritchie Blackmore certainly agreed: “Everybody who’s heard it thinks it’s my best playing in a long time, which I suppose is a compliment,” he said. “Then again, what do they know?”

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #158.