"My dream was a place where we could create and make music and take magic out of the air": Remembering Robbie Robertson, architect of The Band

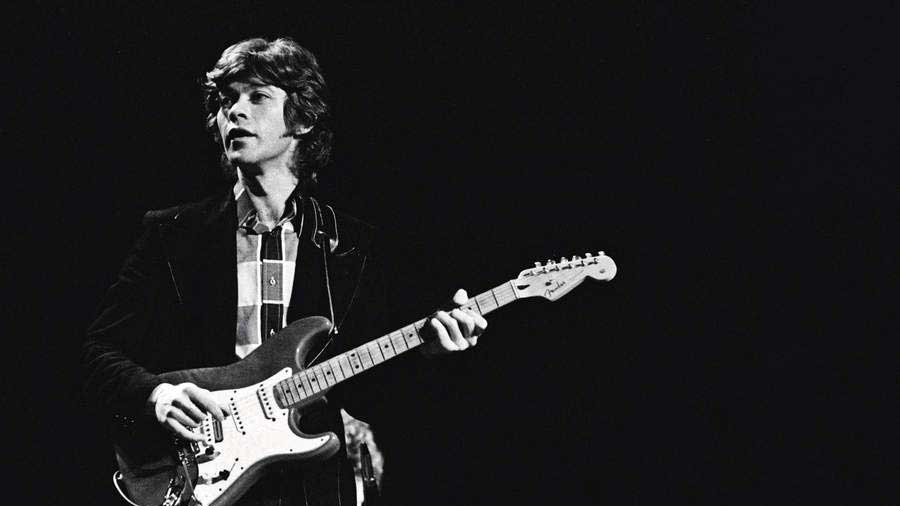

Robbie Robertson was behind two world-changing musical revolutions; a Canadian songwriter and lead guitarist whose group The Band gave birth to Americana

On July 1, 1968, the arrival of the debut album from a curious new group hit the music community with a resounding impact, its waves of influence felt almost immediately. Music From Big Pink was an enigma, sounding rawer and more rustic than the lysergically layered, overblown rock of the day, and feeling entirely out of step with the current fashion.

Its exotic blend of country, gospel and R&B would prove explosively consequential. An enamoured Eric Clapton broke up the virtuosic power trio Cream to pursue similarly down-home ambitions. George Harrison, evangelical with his love for the authenticity of the songs, steered The Beatles back to live studio performances. The Rolling Stones ditched their psychedelic posturing to re-embrace their blues roots. The Who considered its authors bona-fide geniuses.

“Music From Big Pink,” Roger Daltrey told this writer, “was one of the best albums ever made.” From their mountain retreat in upstate New York, this inscrutable collective of four Canadians and one American had inadvertently re-channelled the course of music history. And they didn’t even have a name.

“It came out looking like we were rebelling against the rebellion,” the band’s former guitarist Robbie Robertson told me in 2005. “And perhaps that’s true, but I don’t remember anybody saying: ‘Let’s rebel against the rebellion.’”

At that time, Robertson was one of three surviving members of the group, which would come to be known as The Band, and the sole curator of their legacy, having just produced the comprehensive career-spanning box set A Musical History. It was a role he’d got used to – as the group’s main songwriter and spokesman, Robertson had, in his attempts to harness the potential and power of his increasingly disorderly comrades, become their de facto leader. But it was something of a poisoned chalice; after initiating the group’s split in the mid-70s, Robertson was later unfairly vilified in some quarters, accused of short-changing his bandmates.

It was an unreasonable charge, amplified by the stinging criticism in drummer Levon Helm’s 1993 autobiography, and one that Robertson was repeatedly impelled to answer to. For the few who overlooked his subsequent success both as a solo artist and a renowned film composer, it was only his unexpected death, and the flood of tributes it incited, that allowed them to fully recognise his unerring commitment to preserving the sanctity of the timeless music they created together.

Robbie Robertson died after a long illness, one month after his 80th birthday, on August 9, 2023. He didn’t live to see the release of Killers Of The Flower Moon, his fourteenth soundtrack album, the latest result of his long-time collaboration with director Martin Scorsese, and a testament to the unyielding ambition that drove an exceptional and progressive career that began when he was a teenager.

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

Jaime Royal Robertson had grown up in Toronto, where frequent visits to the Six Nations Reservation (his mother was of Mohawk and Cayuga heritage) had introduced him to the communal aspect of music performance, and led to his parents buying him a guitar. “Then rock’n’roll suddenly hit me when Iwas thirteen years old,” he told Classic Rock. “That was it for me. Within weeks I was in my first band.”

Robbie And The Robots were gigging Toronto’s teen circuit when the 15-year-old guitarist saw the wild stage show of Arkansas rocker Ronnie Hawkins, playing the city with his hot band The Hawks, which included 18-year-old drummer and fellow Arkansan Levon Helm. “I had just never seen anything this excited and spirited,” Robertson would recall of Hawkins’s act, so potent in its dynamics, and authentic in its southern flavour.

Endearing himself to Hawkins with his guitar-playing skills and songwriting aspirations, Robertson was soon brought in as a Hawk, where life on the road was a vivid schooling in musicianship, business, sex and partying for the wide-eyed Canadian.

Hawkins made a habit of refreshing his Hawks with the best young talent he could find or poach. But in 1964, with the tide of youth culture beginning to turn, and the limitations of Hawkins’s strict decrees beginning to chafe, his seven Hawks flew the coop. “We had to find our individual sound and identity, and head in a more ambitious creative direction,” Robertson explained in his 2016 memoir, Testimony.

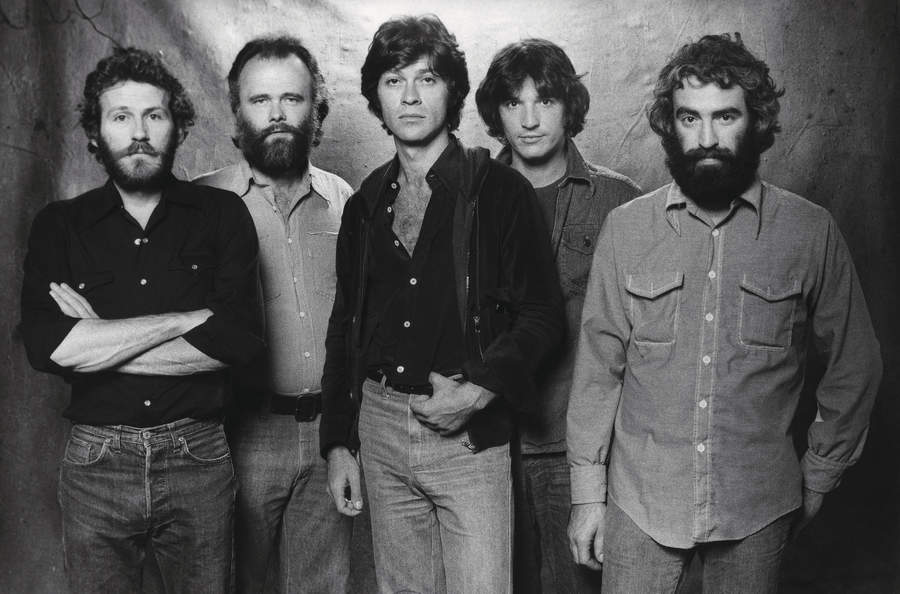

Levon And The Hawks, as they named themselves, made progress with a couple of singles of their own, and by 1965 had reduced to a quintet of Helm, Robertson, pianist Richard Manuel, bassist Rick Danko and organist Garth Hudson. Making headway independently, the last thing they were looking for was another bandleader.

Robertson first met Bob Dylan in August 1965. In considering a stylistic shake-up, the folk music poster boy had fielded recommendations for a backing group, and heard about the Hawks. Robertson, unaware of Dylan’s prestige, was taken aback by his request for the Hawks to electrify his sound. “We weren’t into folk music at all,” he told me. “We were from the other side of the tracks.”

Nevertheless, an intrigued Robertson floated the idea with Helm, and the pair played a couple of shows with Dylan to test the waters. Dylan attempted to lure the pair into his current band, but Robertson was intent on convincing him to hire the Hawks as a unit. With The Hawks behind him, Dylan embarked on a notorious world tour, where the musicians nightly faced a barrage of boos from folk purists horrified by amplifiers.

Dylan defiantly dragged his disapproving disciples into a new, cultivated era of rock’n’roll, with Robertson watching the bard from his side, soaking up a wealth of information through their shared interests in music, literature, poetry and movies. The negative reactions were too much for Helm, who quit in autumn 1965. “We were on the inside of a musical revolution and didn’t really know it,” said Robertson.

Dylan’s thin, wild mercury streak came to a sudden halt with a motorbike crash in Woodstock, New York in July 1966. While he was recuperating, Robertson and his girlfriend Dominique (whom he’d marry in 1967) moved to the area with Richard Manuel, Garth Hudson, and Rick Danko living together nearby in a salmoncoloured house they dubbed Big Pink.

The musicians would gather with Dylan in that house’s basement to write and record, amassing hundreds of songs that served not only to provide Dylan with material to offer out for publishing, but also, through endless playing in such an intimate setting, reshape the Hawks’ sound into a something softer and distinctly pastoral.

“This had been a dream of mine, to have a workshop, a clubhouse, a place that we could go every day and create and make music and take magic out of the air,” said Robertson, “and it would be our own atmosphere and our own sound – everything that we had been building and gathering over the years.”

Those songs were enough to lure Helm back into the fold, and also land the group a contract with Capitol Records. Music From Big Pink would follow, a natural evolution from those basement sessions, which sounded as basic, woody, and comfortable as the room it came from. The album, and the group, became a phenomenon. Four of the songs on Music From Big Pink, including future classic The Weight, were credited to Robertson, but it was on their second album that he truly flourished as an accomplished storyteller.

When The Band was released in September 1969, it finally confirmed the identity of the group, their unpretentious moniker a reflection of their humble means and indomitable brotherhood. “Everybody held up their end and played an extremely important part in it,” enthused Robertson, who stepped up on the songwriting front to deliver all 12 of the album’s songs (including four co-writes).

The songs, imbued with the bronzed hues of an autumnal Woodstock saw Robbie reach into the well of American history and mythology to write songs that celebrated a country currently at war with itself, and were designed to be expressed by each of his bandmate’s individualistic voices.

On the album, Richard Manuel’s evocative pining in Rockin’ Chair and wails of desperation in King Harvest (Has Surely Come), Rick Danko’s bittersweet melancholy in The Unfaithful Servant, and Levon Helm’s masterful bruised pride in The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down, all owe their being to the fertile imagination of Robbie Robertson, who created each character specifically for those qualities to be conveyed.

As a guitarist, Robertson’s style had evolved far beyond the flashy soloing that Ronnie Hawkins demanded, and now echoed The Band’s understated grace, where subtleties dominated until virtuosity was required. His solos on record were scarce, but impassioned and evocative when unleashed. “Robbie was the type of guitarist who was more concerned with the overall song and structure than his own personal prowess,” George Harrison said.

The Band’s star rose through the early 70s, but with success came the trappings of fame. Drug addictions crippled songwriting contributions from the rest of the group (with the exception of Hudson), and as their albums mounted up (the great Stage Fright, the middling Cahoots), so too did Robertson’s responsibilities as a writer and creative director. “I wasn’t trying to be leader or anything else,” he said, “I was just doing what I had to do.”

He spearheaded a move to California in 1973, settling in Malibu with the intentions of founding another clubhouse there. (Their studio, Shangri-La, opened in 1974, and is now owned by Rick Rubin.) But the change of scenery did little to abate The Band’s unbalance, and Robertson sought an escape.

After touring their final studio album, Northern Lights – Southern Cross in 1976, he suggested to The Band that they pause to recover.

“The natural thing was to find a cave, a quiet place to heal, and then – hopefully – return with a vengeance,” he wrote in Testimony. “I proposed that we go underground and let the dark clouds pass over. Nobody had the answer, but something inside of me said: ‘You boys gotta get off this train.’”

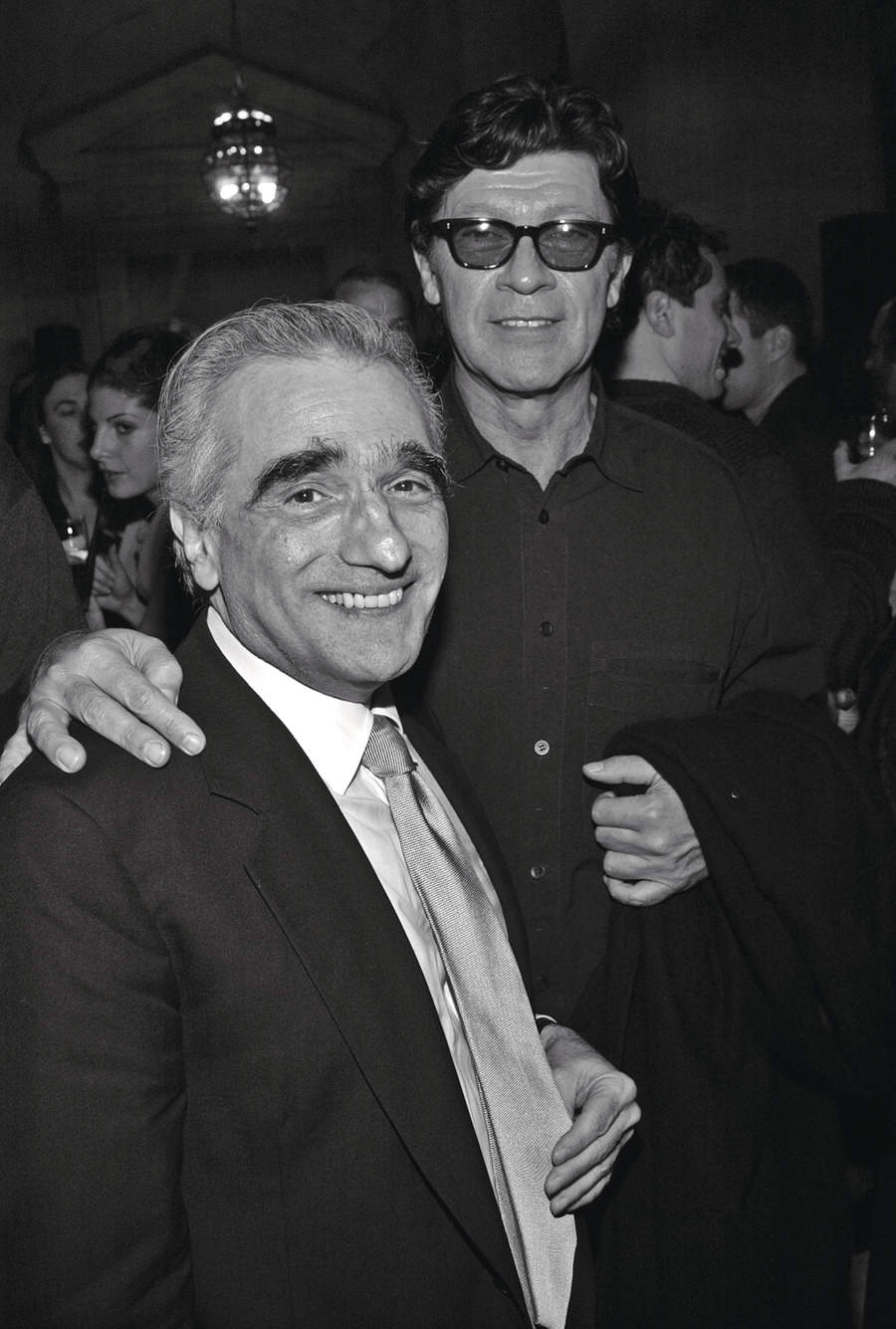

A celebratory farewell concert was planned for Thanksgiving 1976, and, after Robertson met up-and-coming director Martin Scorsese, it was to be filmed for posterity. The Last Waltz is an iconic document of a magnificent finalé to The Band’s glory years. With guest turns from Dr. John, Muddy Waters, Joni Mitchell, Neil Young, Eric Clapton and Bob Dylan, it’s a veritable immortalisation of The Band’s importance and the reverence in which they were held by their peers. By the time it was release in cinemas in 1978, The Band had irrevocably splintered.

Robertson’s post-Band career was primarily in the movies. A starring role alongside Jodie Foster in 1980’s Carny gave way to work behind the cameras. That year, he assisted Martin Scorsese in compiling the soundtrack to Raging Bull, initiating a partnership that endured until Robertson’s death, producing over a dozen musical backdrops to films including The King Of Comedy, Casino, Gangs Of New York and The Wolf Of Wall Street.

It was Scorsese’s 2019 film The Irishman that galvanised Robertson to write his own original material again, and that year’s Sinematic became only the fifth album in a solo career that began with his acclaimed self-titled debut in 1987.

I had met Robbie in London in 2011, around the release of How To Become Clairvoyant. He explained that the infrequency of his output was due to his rejection of music industry expectations. “I’ve been to that place of where you had to make a record because of deadlines and because of schedules and everything,” he said, “and I choose not to have that any more. I’m off that treadmill. I’m just following my instincts, really.”

The following year, Levon Helm died of cancer. He had long blamed Robertson for The Band’s break-up (they regrouped without Robertson in 1983, continued after Richard Manuel’s suicide in 1986, and finally ended – after three respectable albums – with the death of Rick Danko in 1999), and his aggrievement over publishing royalties rankled. At their request, Robertson had bought the publishing stakes of Manuel, Danko and Hudson when they faced financial distress, while Helm, who was still receiving one-fifth of the collective income, argued over song credits.

Robertson refused to rise to the claims. “I never had an issue with Levon,” he told Classic Rock in 2019. “He was having a tough time, and he blamed me. He was so great at playing and singing, but he wasn’t great at taking responsibility for stuff.” The pair reportedly cleared the air in Helm’s last days.

Robbie Robertson died at home in the company of close family including his wife, Janet, ex-wife Dominique, and children Alexandra, Sebastian and Delphine. Tributes were plentiful. Stephen Stills, Ronnie Wood and Ringo Starr – all Last Waltz participants – paid their respects. Martin Scorsese called Robbie a “giant”, adding: “His effect on the art form was profound and lasting.” Bob Dylan said Robbie was a “lifelong friend”, and his death “leaves a vacancy in the world”.

In reevaluating Robertson’s life in music from this perspective, it is difficult to deny the genius and generosity that shone through. From the moment he helped bring the cream of Canada’s barroom circuit in to the Hawks, he batted for his brothers every step of the way. It was Robertson who sold them wholesale to Bob Dylan, who furnished them with astonishing, rich material that provided their livelihood, who sought to encourage their creativity, who supported them in their time of need.

His captivating memoir, Testimony (volume two was in the works), was adapted into the excellent 2019 documentary Once Were Brothers, which in turn was named after a song on Sinematic. That song was a poignant reflection on his connection to his friends in The Band (of whom Garth Hudson is the last man standing), and a stirring swan song that book-ended an outstanding career. ‘When that curtain comes down,’ he sings, ‘we’ll let go of the past/Tomorrow’s another day, some things weren’t meant to last.’

Simon Harper is a co-founder of the award-winning music and fashion title Clash Magazine, and its Editor-In-Chief since launching in 2004. A lifelong Beatles fan, he has worked on a number of projects with Paul McCartney since interviewing him for a Clash cover story in 2007.