This article first appeared in The Blues #2, August 2012.

“Sometimes”, Bob Dylan once sang, “even the President of the United States must have to stand naked.” And sometimes even the President of the United States ends up as just another notch on Robert Cray’s guitar.

“We had the good fortune of doing a benefit for the President last year in Seattle, Washington, and we were in the meet-and-greet line, and there’s always a person there to introduce the President to whomever’s coming next, and he goes, ‘Mr President, this is Robert Cray…’ ‘I know who Robert Cray is! I got him on my iPod!’” Robert Cray chuckles, which he does often. “That was great. That made me feel really good.”

Robert Cray on Barack Obama’s iPod? Why not? After all… it makes perfect sense. Born in Hawaii and partly raised in Indonesia he may be, but President Barry is a classic soul man from Chicago, some eight years Robert Cray’s junior, and he’d’ve been all of 25 years old back in 1986, when The Robert Cray Band defied all the conventional wisdoms of the blues economy by zooming their Grammy-winning fourth album Strong Persuader into the Top 20 (with its featured single Smokin’ Gun reaching No.22) and their leader’s handsome mug, plangently soulful voice and viciously spiky guitar were all over MTV. Just as his white Texan contemporary Stevie Ray Vaughan was earning definitive rock star status, Cray became a bona-fide pop star, and in the following decade the new blue wave they jointly launched refloated the becalmed careers of their own heroes John Lee Hooker and Buddy Guy. Frankly, it would’ve been weirder if Cray’s music had not been on Obama’s iPod.

For a few years, Cray seemed to be everywhere: guest starring at the featured concert, musically directed by Lord Keef, in the Chuck Berry doc Hail! Hail! Rock And Roll, and in Tina Turner’s Break Every Rule TV special, not to mention co-writing songs and studio-collaborating with Eric Clapton and even popping up to sing a line in the BBC’s all-star version of Lou Reed’s Perfect Day.

Even before that burst of pop success, the blues community had already taken Cray to its collective heart. Phone Booth, the lead-off track from the band’s 1983 second album, Bad Influence (that and its follow-up False Accusations were the first two blues albums ever to top the UK indie charts) was rapidly covered by Albert King, who made its now-legendary opening line – ‘I’m in a phone booth, baby’ – the title of his next album, and you can’t get much more blues-approved than that… other than recording with John Lee Hooker, and a few years later Cray would do exactly that.

Cray was both one of the most successful of his contemporaries and one of the least typical. For a start, while the band are fully capable of delivering archetypal blues tropes like uptempo shuffles and wracked slow blues done to the proverbial turn, they don’t choose to do so very often. What they do do, and always have done, is to play ‘minor-key mid-tempo cheatin’ songs’ in a classic mid-60s Southern-soul vein, soaked to the bone in a Memphis marinade which recalls the golden years of Stax and Hi Records. Think Steve Cropper and Willie Mitchell; think Al Green in his earliest, bluesiest vein; think Albert King backed by Booker T And The MGs (hell, at the height of his fame and success, Cray was able to hire the Memphis Horns: saxophonist Andrew Love and trumpeter Wayne Jackson – the guys who’d cut with Otis Redding and Sam & Dave – to record and tour with him); think Bobby Bland and (Cray’s own all-time favourite soul man) O V Wright.

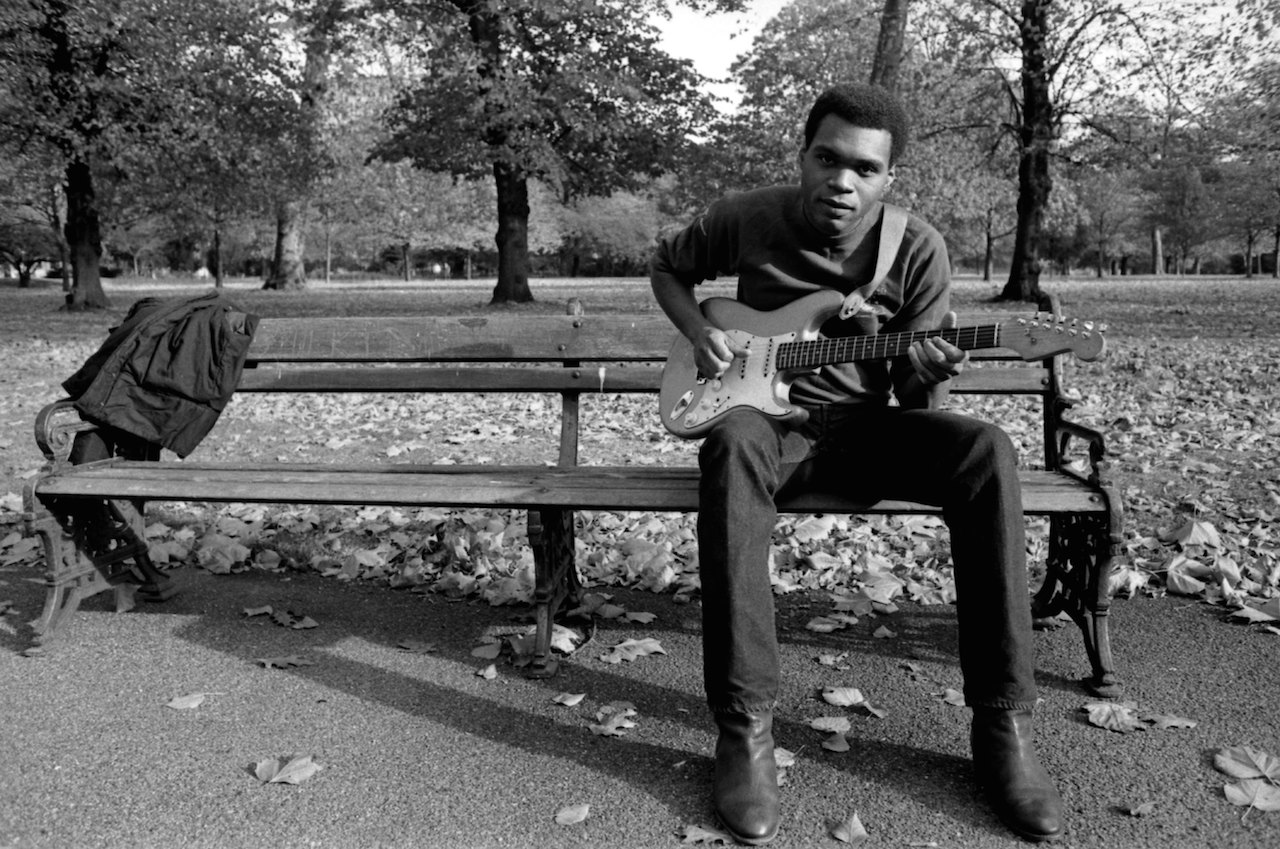

And all of it spiked with seriously nasty blues guitar solos inspired by the late and much-missed Master of the Telecaster, Albert Collins (whom the fledgling Cray Band backed live for several years) and served up smokin’-gun hot with the energy and groove of musicians who may play soul and blues but who were raised on rock.

The pop success eventually receded. Three or four albums on from Strong Persuader, the Cray Band’s records only reached the 50s on the mainstream charts… and then the 100s… and then they stopped showing up at all. The loyalty of the blues audience remained strong, however: the band kept playing and the people kept coming.

And – never forget – it is a band: a team effort. That’s why it’s always been ‘The Robert Cray Band’ rather than just ‘Robert Cray’. Even though there have been complete personnel turnovers (apart from yer man hisself, of course) with many musicians coming and going (and only original bassist Richard Cousins ever returning), all the various Cray bands have always functioned as songwriting collectives with all members contributing and also, during the 1980s, their songwriting label bosses/producers David Walker and Bruce Bromberg. The catch is that every song, whoever originates it, has to pass the Cray Test: the man who’s going to have to deliver the song, onstage and in the studio, has to feel able to deliver it with such absolute conviction that, ultimately, it won’t matter who wrote it. By the time it gets sung, it’ll be a Robert Cray song. As Peter Boe, who occupied the keyboard chair during the Persuader era, once told me, “It’s very much a band, but in terms of it being a product of one specific person’s vision of the emotional content of the music, that would be Robert’s chief contribution – outside of singing and playing… all the rest of the guys keep that in mind when they write.”

So: it’s been a while since your correspondent last saw the Cray Band, and now here they are playing a near-as-dammit-full Shepherd’s Bush Empire on an overcast Tuesday night. There’s Cray in his rightful centre-stage spot: from the balcony he doesn’t look that much different – other than a minimal thickening of the torso – from the way he looked 30 years ago. And there’s Richard Cousins, Cray’s teenage buddy and mainstay of the original line-up, lurking in the shadows of his Ampeg bass stack: lankily and insouciantly elegant in his baggy pinstripe suit and caught-up dreadlocks, alongside long-serving keyboard guy Jim Pugh and relatively new drummer Tony Braunagel.

From the first few bars it’s apparent: the snap is back. Karl Sevareid, who replaced Cousins during his lengthy sabbatical, was a fine musician who never put a recorded finger wrong the whole time he was in the band, but sometimes the grooves he and then-drummer Kevin Hayes created had an unfortunate tendency towards stodginess. Cousins’ return seems to have relit fresh fire under the man he calls ‘my boss’: when combined with Braunagel’s drumming, it’s safe to say that, for the foreseeable future, no one’s gonna be catching the Cray Band with their funk down.

Cray himself sings and plays his bits off, as he always does (whatever the relative merits of the various Cray albums, none of them can ever be faulted for any lack of passion and commitment on the leader’s part) and his between-songs patter is warm, engaging and urbane. (‘Twas not always thus: when he first started fronting the band, he was so nervous about talking to audiences that the more extrovert Cousins had to introduce the songs.)

Nevertheless, he refuses to trade on easy familiarity and makes no concessions to anyone in the house who’s hung up on his 80s hits until Smokin’ Gun is wheeled out almost at the end of the set. It’s the newer songs that matter most to him, and thus almost everything the band play comes from the last few albums. Despite kicking the obvious crowd-pleasers to the kerb – no Phone Booth, no Right Next Door, no Bad Influence – they righteously rock the house despite their trademark refusal to end with a boogie. Of which more later…

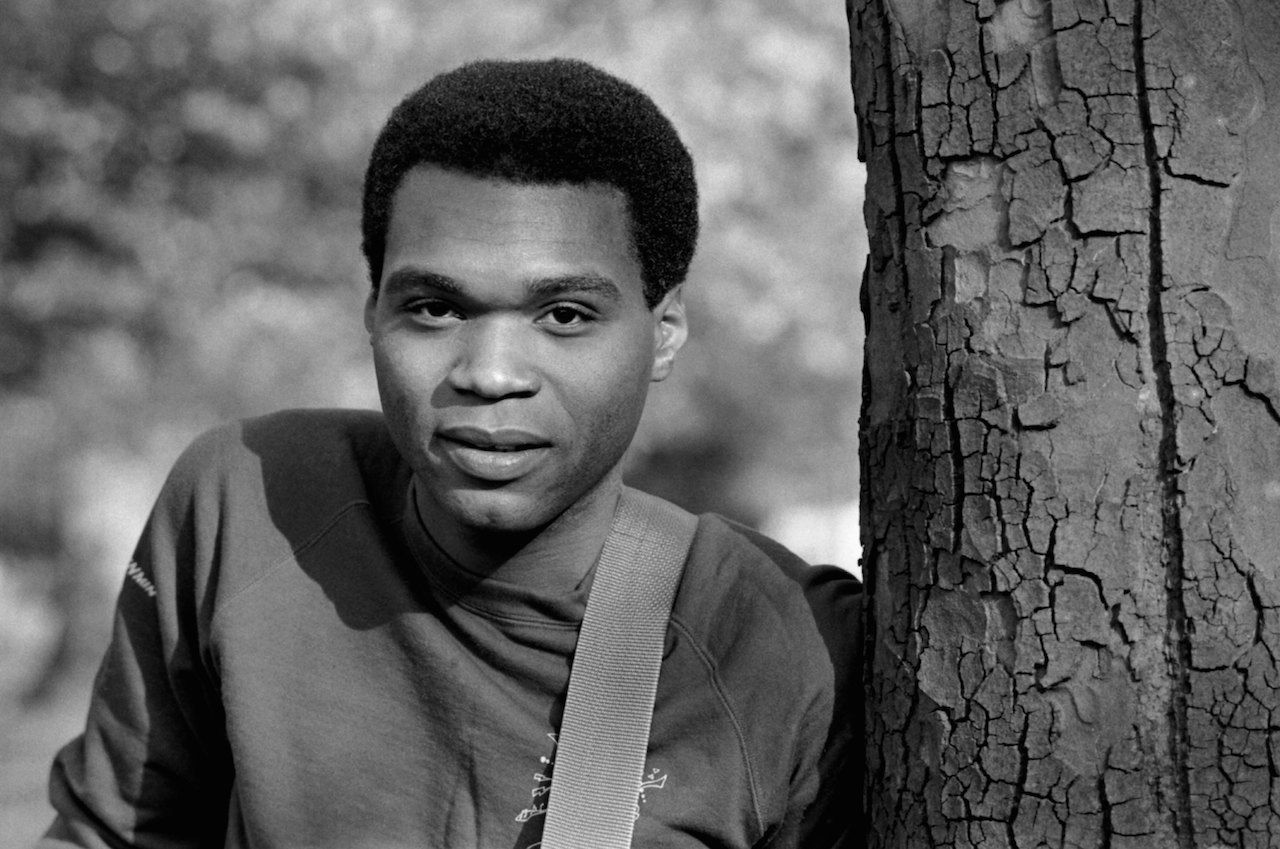

The following day, on a sunny afternoon to gladden Ray Davies’ heart, Cray – in baseball cap, sweatshirt and shorts, and still looking eerily youthful despite being only a year or so shy of his 60th birthday – sits down to discuss his band’s 16th album, Nothin’ But Love, produced by Kevin Shirley, who does the biz for Joe Bonamassa, and including songs about the state of the world rather than just the troubled love life of Cray’s musical alter ego Young Bob. (Whatever his songs might suggest, the real Cray has been married for 22 years and he’s accompanied on this tour by his five-year-old son and ‘lavly’ English missis.)

So what was the inspiration?

“The inspiration is what’s going on around us. Ever since George W Bush was in office in the United States it’s made more people – especially in my age group, with the advent of the 24-hour news-cycle – more politically aware, so we know more about what’s going on around us: certainly more than I maybe would’ve known, or paid attention to, 20 or so years ago. The housing crisis and the mortgage crisis and the banking crisis put a lot of people out of their homes.

“Watching all that on the news, watching the ‘For Sale’ signs go up in the neighbourhoods and even on the street where we live, inspired a couple of songs on Nothin’ But Love, in particular: Great Big Old House and I’m Done Cryin’, which also deals with jobs in the recession goin’ on.

“And there’s another, which was written by Richard Cousins and his friend Hendrix Ackle, which is called A Memo and it’s supposed to be the President of the United States telling you, ‘I’m gonna warn you, it ain’t over yet/Got you out the hot water, but you’re still all wet/if you don’t pay attention you’re gonna get what you deserve’.”

- Ten pivotal dates in the chaotic career of Chuck Berry

- Call And Response: Robert Cray

- Albert King: "We weren't thinking blues, we were thinking dance music"

- Muddy Waters Buyer's Guide

Well, maybe Obama will sing it. He does a pretty good Al Green impression…

”[Laughs] He does do a good Al Green! And you know what? When he sang it, just off the top of his head, he sang it in the right key of the original song!”

How’d you hook up with Kevin Shirley?

“It’s because of the record label: Joe Bonamassa and I are both on Provogue now, and Kevin and I talked about how he likes to do stuff, and what we like to do, and we got along great. He loved the idea of working fast, which is how we liked to work: we don’t like the idea of working on anything for any great length of time. Just move onto something else if it’s not happening, and try to capture a live feel. It worked out and it was cool, because the last record I pretty much did the production on it, and it was nice to have someone else take the reins.

“When we started working, we could tell from the very first efforts… because Tony Braunagel, our drummer, has produced records, and Jim’s produced records and Richard’s done production… it was like, ‘Hey, this guy, let’s check him out, he’s got these rock credentials…’ Kevin knows his stuff, and he took the ideas that we brought in, and took a different look at the songs… and we thought, ‘This is cool.’ We had a good time and we were all on the same page. The album only took two weeks to record.”

[For his part, Shirley told this magazine last month, “To be honest, Robert only had 11 songs, but they were good ones… after two weeks I said, ‘I think we’re done’ and he said, ‘Okay, I’m going home!’]

Robert Cray may have been born in Georgia (which is fo’ sho’ the South, y’all), but his route to the blues was characteristically untypical. I mean: The Beatles?

“My father was in the army and we did a lot of travelling around, but my parents had a great record collection: from Ray Charles to Sarah Vaughan, and on Sundays my father would listen to gospel music such as The Dixie Hummingbirds and The Swan Silvertones. Mom was into Bobby Bland, Jackie Wilson and Sam Cooke, of course. That was stuff we listened to throughout all our moves, especially when we were in Germany during the early 60s. We bought a lot of records there, so I know that my dedication to listening to records began then. And when The Beatles came out, everybody got a guitar. I followed suit, and it was all about learning anything that you could pick up, so I listened to everything that was on the radio. I was a Beatles guy!”

I’d have thought you’d have ended up liking the Stones better, because of…

“Their blues thing? I didn’t go there at that time. I dug the Stones, but I was a Beatles fan! I liked what they were doing. I mean, I liked what the Stones were doing too, and I remember when they were playing on the Shindig! TV show and they brought Howlin’ Wolf…”

Yeah, I nearly had an argument about it with Buddy Guy a few weeks back, he swore that it was Muddy.

“Yeah, I read that in his book! No, it was Wolf. I saw it! I listened to all kinds of music. I listened to Peter Green’s music, I listened to Eric Clapton’s music, I saw Jimi Hendrix a couple of times when I lived near Seattle. And, towards the tail-end of my high school days, there was a bunch of friends who played guitar: Bobby Murray – who spent a lot of time in Etta James’ band: we grew up in the same neighbourhood – and Richard Cousins and myself.”

It was Albert Collins who provided Cray’s blues epiphany when he was booked to play the friends’ high-school dance… and it was also Collins who gave the youthful Cray Band – Cray had considered himself mainly a guitarist until the band’s singer bailed on an audition, forcing Young Bob to take the mic he never again relinquished – their first lessons in hands-on bluesmanship. The band had played a successful three-night club gig and the owner invited them to stick around and back up Mr Collins, who was then travelling solo without a group. Since they loved his music, and already had a few of his songs in their set, they jumped at the chance. Being sticklers for structure, they were dumbfounded to find themselves on stage jamming on Sly & The Family Stone’s Sex Machine (no relation to the James Brown piece of the same name) for up to 15 minutes at a time while Collins prowled the halls, soloing at the end of a 120-foot cable.

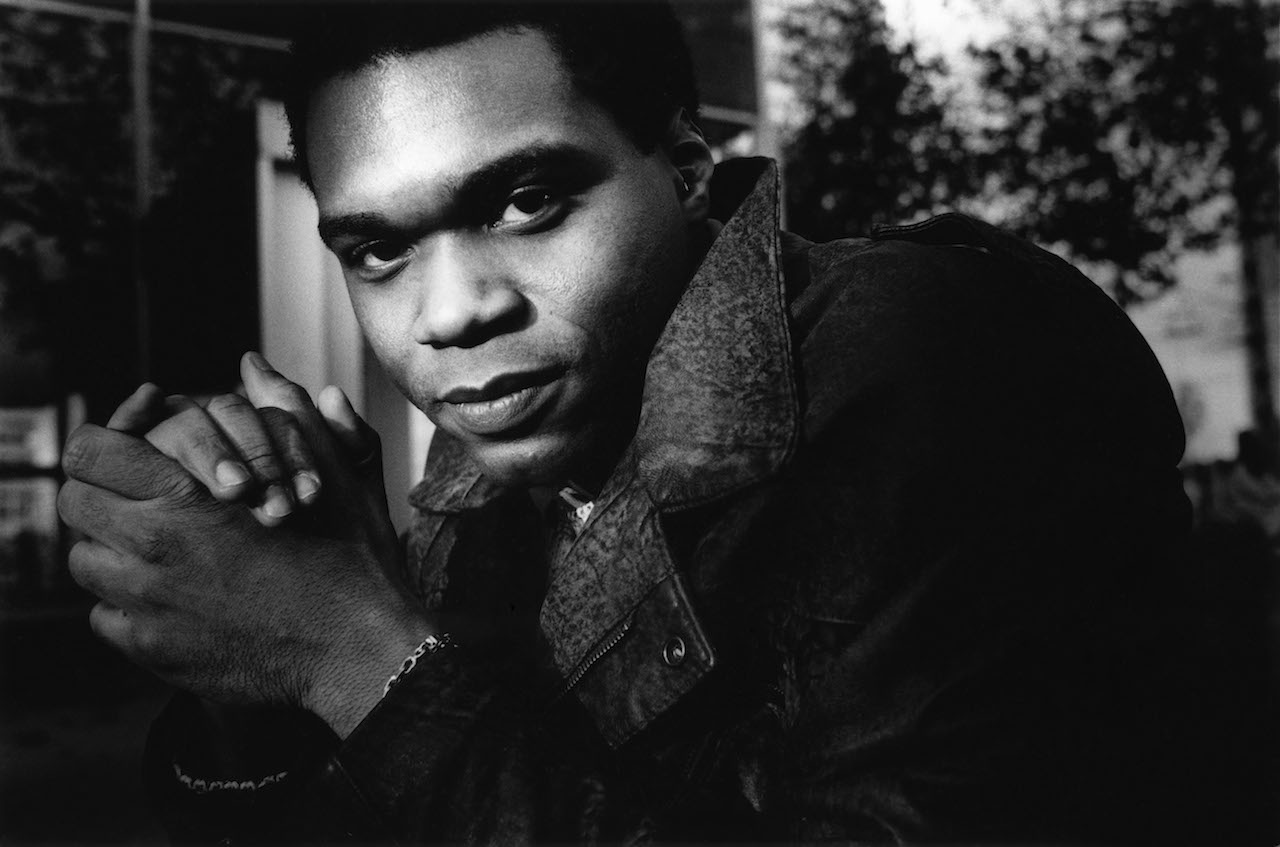

For almost a dozen years, the Robert Cray Band worked the West Coast blues circuit, playing bars, clubs and the occasional festival. They finally cut their first album, Who’s Been Talkin’, in 1980 for former Stones and Yardbirds honcho Giorgio Gomelsky’s Tomato label (which, in its heyday, had released records by John Lee Hooker and Albert King), but the label folded on them before it could be released and it didn’t emerge until two years later, on Davd Walker and Bruce Bromberg’s tiny Hightone label. Their second effort, 1983’s Bad Influence, was picked up by the UK’s Demon label and hit like blues albums generally don’t. It made the band, still only regionally known in the US, seriously hot in Britain – following a tour highlighted by a sizzling Dingwalls show which your correspondent was privileged to attend – and, with little fanfare, went on to sell a million copies. The genial, unassuming Mr Cray – then just hitting 30 – was about to redefine the notion of what ‘blues stardom’ could mean.

Since the heady pop star days of the 80s, his career has slowed, but never stalled. He never got what John Lee Hooker called “the big head”: a dozen years of scuffling, and his own innately level disposition, saw to that. And he remains not only one of the biggest names in his field, but one of the most-respected and best-liked.

How do you see the state of the blues these days?

“I see a lot of the people I’ve known for a long time still out there workin’. Just a month ago I saw Lou Ann Barton working with Jimmie Vaughan: we did a gig together. We did a festival in Ottawa and John Mayall was on the bill. Everybody’s working, a lot of people are working. In the summer it’s blues festival season, and a lot of the clubs still feature blues in a big way. People are playing the music but adding their own flavour to it.

“Everybody’s talking about Gary Clark Jr, who I was turned onto by Keb’ Mo’, who showed me a YouTube clip of him playing a gig in Austin, Texas – this was about four, five years ago – he said, ‘Look at this, Cray!’, and there he was, fronting a horn section of guys all at least 20 years older than he was. He’s in his twenties, but he was like a 60-year-old. He’s adding his own flavour in terms of what he can relate to and what’s around for a kid in their twenties, which is the hip-hop thing. He’s got a good musical sense and great taste. When I hear hip-hop, it’s a different generation to me and I go, ‘Urrrrghhhhh!’, but it’s him pushing the stuff forward and it’s cool.

“When the rap thing started, there was a lot of hatred towards it among the R&B musicians. I remember being here in England in the 80s, doing an interview for some magazine and somebody said to me, ‘What do you think of rap? Do you think it’s going to be be around much longer?’ and I said, ‘Nah, it’ll probably be gone year after next!’ [laughter]. I made a stupid statement like that, and it’s been almost 30 years now!

“I don’t know anybody else outside of who I just mentioned… there are guys who are sort of ‘in between’, Derek Trucks or Jonny Lang, Susan Tedeschi… but I don’t know everybody that’s out there. That’s about it for my list so far, but I know it’s out there, because there are too many people that care. The long-term fans are bringing their kids and sometimes when I’m signing autographs after the show they say, ‘My parents told me: if it wasn’t for that Strong Persuader record I probably wouldn’t have been born!’ or, ‘My dad turned me onto that record, man!’. I tell that to my wife and she says, ‘See? Now you’re a legend!”

Do you still believe that if it ain’t a sad song it ain’t the blues?

“I do! I think that a blues song is a sad song! That’s just my personal thing. I know that there’s a form of music called ‘the blues’, but nobody’s going to tell me that My Babe by Little Walter is a blues song – it’s blues in terms of the musical changes, but it’s not a sad song. Or They’re Red Hot, by Robert Johnson.”

And Muddy’s Got My Mojo Workin’?

“That’s rock and roll, man! [laughter]. Though, ‘but it just won’t work on you’ is the blues!”

You’re a bluesman who mistrusts pleasure, and a soul man who denies redemption. You don’t end your shows with a boogie or a rocker, so in a sense you give your audience no release from the wrenching soul-blues noir songs you sing. What’s that about?

“You know what I’m thinkin’? It’s like me. I like emotional music. Everybody likes emotional music. It’s the kind of stuff that stays with you, and I guess maybe that’s the reason for doin’ that. For the longest time we’d end shows with Time Makes Two, and last night we did I’m Done Cryin’. I guess it’s that thing where you don’t have to pound people over the head to get to them.”

John Lee would have ’em weeping in the aisles, but he’d always send ’em home with the boogie, because he wanted…

“…To end on a good note, huh? I can see that, and I can understand that. For someone who’d been around as long as John Lee, playing to his home crowds in the early days, people who worked hard in the factories and had to have that release, drown their sorrows, make ’em feel good. Not that it’s any different for people working their gigs today, but maybe it is in the sense that it’s not quite the same as that. Maybe I’m just being selfish but that’s where my heart is. Thinking off the top of my head to one of my favourite albums, Nucleus Of Soul by O V Wright. The last track is called I Want Everyone To Know, and it’s my favourite O V Wright song, and that song closes the album – it’s a ballad. And it ends with him squalling, ‘I want my mother, my father, my sister, my brother… to know that I love you.’”

Well, that’s an album rather than a live show and some of my favourite albums end on something deep, but I’m thinking about the way you almost subvert the ritual of performance because everybody ends with a rocker. Everybody ends on a boogie or a stomp, except you.

“It’s not that we haven’t done it before. Nowadays the regular set ends with Smokin’ Gun and when we come back for the encore we close down with a ballad.”

When we first met you were the new guy, and now you’re a frontline elder statesman.

“It’s a funny way to think of it but, wow, yes, I guess I am getting older. When you play and you have fun doing what you do, you don’t think of it. We’re all getting older and it must be hard if your mobility is compromised, but your brain still tells you you’re still the same person you’ve always been. When I started it was just about having fun and playing. I was hanging out with my good friends: Richard Cousins and whomever else was in the band and every time we got a gig it would be: ‘San Francisco Blues Festival? Great!’ or being on stage with Albert Collins and just looking at each other and smiling – what a great time! Getting the opportunity to play with Muddy, or to play with John Lee or Albert King – the guys whose records we used to try and learn the songs from – we were like a leaf being blown in the wind, just going wherever it took us. We’re still making a living at it.”

Interview concluded, your correspondent is in the hotel bar passing the time with the band’s PR and a couple of bottles of Czech lager, when in strolls Richard Cousins.

“Someone’s got to be the clown of the band,” he once told me, but I’ve always thought of him as the Cray Band’s Ron Wood: the mischievous cheeky chappie whose function – on- and off-stage – is to gee everybody up and bring the fun in. Since 2008, he’s been back in the band he co-founded when barely out of his teens and which is manifestly benefiting from his presence. “It feels good: there’s a different energy to before, with Richard’s camaraderie and that spark that’s always there,” says Cray.

Beer in hand, Cousins happily settles back to dish the dirt and gracefully accept a compliment on his rather magnificent crown of dreadlocks (“Going grey, though. I don’t use products like my boss!”) before regaling us with a few anecdotes from his years backing Etta James in a band which also included guitarist Bobby Murray (another old buddy from his and Cray’s teenage years) and drummer Tony Braunagel, whom he brought with him when he rejoined Cray. Braunagel, incidentally, was “virtually a house drummer for Island Records in the 1970s” and played alongside the troubled ex-Free guitar star Paul Kossoff in Back Street Crawler.

Tell Robert Cray he’s now one of the world’s greatest living bluesmen and he’ll simply deflect: go into modest mode and murmer, “Thank you, man. That’s nice!” Nevertheless, he is. And the new album proves the Strong Persuader has lost none of his strength, nor his powers of persuasion. Back in the day, one of BB King’s intro lines was ‘the dynamic gentleman of the blues’. In 2012, no one has a stronger, or more persuasive, claim to that description than… Ladies and gentlemen, Robert Cray!