As founder, guitarist and de factor leader of King Crimson Robert Fripp can lay claim to being one of the founding fathers of progressive – even if it’s a label he dislikes. In 2014, years before he became an unlikely internet star, Fripp brought Crimson out of deep storage following one of their lengthy hiatuses – and he was ready to make “a joyous racket” once again.

In one of the more welcome returns of 2014, Robert Fripp re-emerged to front a new version of King Crimson. It was a move as unexpected as it was plain bloody marvellous, given that founder member Fripp had more or less retired from active service, largely due to a lengthy spat with Universal Music Group over rights to his back catalogue.

“From 1991 onwards, I was in dispute, litigation and dissension with management and record companies,” he tells Classic Rock. “It lasted until last year, when the final major problem with Universal was settled out of court. An immediate new beginning in the aftermath was the ninth incarnation of King Crimson.”

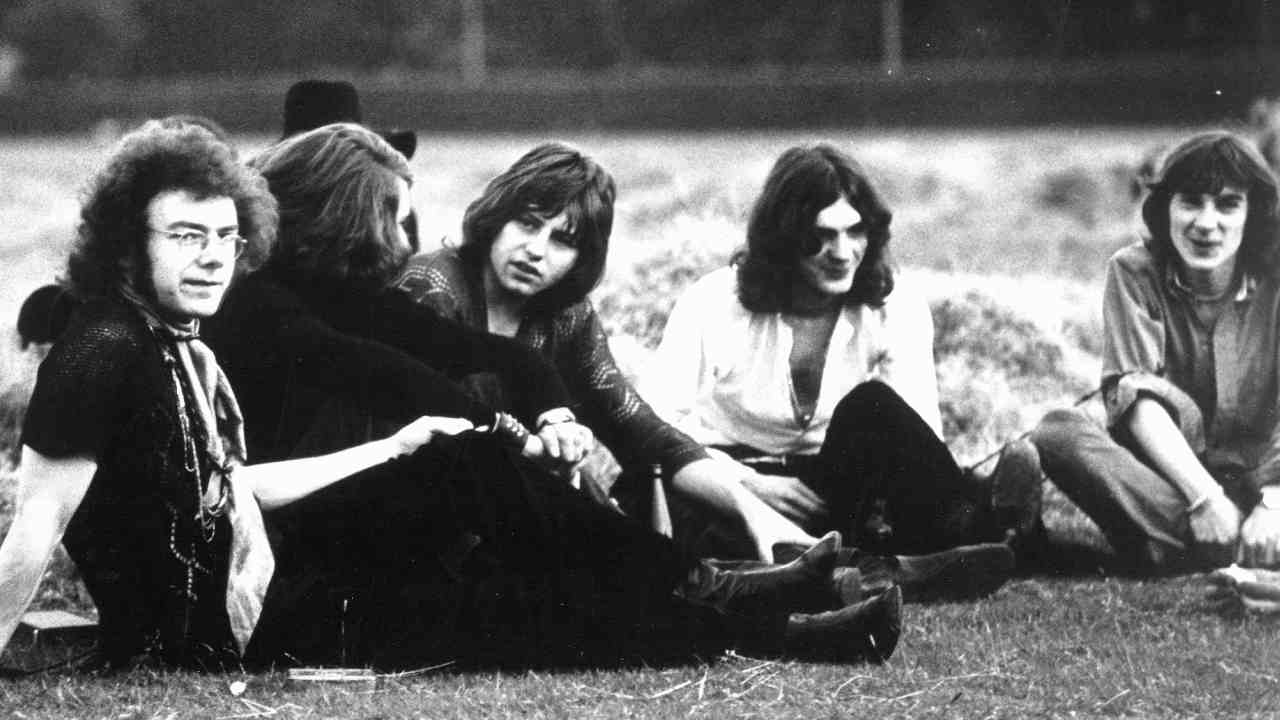

The progressive legends hadn’t played live since a brief swing around the US in 2008. This time around, Fripp decided to hit the road with a highly ambitious set-up that included three drummers stage front (Pat Mastelotto, Gavin Harrison and Bill Rieflin) and a backline of bassist Tony Levin, sax player Mel Collins and guitarist/singer Jakko Jakszyk. Plus, of course, Fripp himself as main guitarist. In what turned out to be an act of purely accidental symmetry, the new line-up finished rehearsals at the end of July, exactly 45 years since the band recorded groundbreaking debut In The Court Of The Crimson King. Their subsequent US tour of the early autumn proved to be a huge success.

Today, he’s content to guide us through a pivotal year in a rich life that’s also included some extraordinary collaborations with David Bowie, Peter Gabriel, Brian Eno, Talking Heads, Blondie and many more. But be warned: don’t ever call him prog.

What’s your assessment of the recent King Crimson shows?

I would describe it as very close to a joyous racket. King Crimson, as a band, is really for the hot date. If you don’t get it live, you don’t capture it. Even our first album, In The Court Of The Crimson King, didn’t really come close to what the band could do live.

The setlist included many songs that Crimson hadn’t performed since the early 70s – Starless, Sailor’s Tale, Larks’ Tongues In Aspic and so on. Was there much trepidation in taking them on?

Yes. For a man of 68 to revisit classics from 40 years ago, from my youth, was a concern. The audience at the time, in the mainstream, didn’t actually like the material very much. But 40 years later, it’s taken on a different hue. Particularly since I now use a different guitar tuning, which makes some of the originals impossible to play in the same way. But the aim was to enter into the spirit of the music. And we managed to do that, surprisingly. One King Crimson principle is that the music is new whenever it was written, even if it was written 45 years ago. The newness is an attitude. It’s the divide between the professional player and the artist. The professional knows exactly what they can do and they’re utterly reliable. That holds no interest for me whatsoever. Someone once asked Elvin Jones, John Coltrane’s drummer, what mindset he adopted on stage. He said: “You have to be prepared to die with the motherfucker.” That’s the level of intensity that you recognise as a musician.

Have you ever found yourself playing in that ‘professional’ mode?

There was one performance with King Crimson, at Preston in 1971, where I just ripped off a lick. And I felt like I was lying to my mother. It was awful. That was the first and last time.

After the final 2014 gig in Seattle in October, you’d already decided to carry on as a live unit?

Yes, we’d already arrived at that. It was so obvious that this was something rather exceptional. After that show, we all came off stage and ate cake together. It was a wonderful key lime pie, from a restaurant about a block away from the hotel. Bill Rieflin, our Seattle resident drummer, acquired it for a sit-down treat.

2014 also saw the release of Fripp & Eno: Live In Paris 1975, which took improvised performance to a whole other level. What are your memories of those shows?

Five minutes before we went on stage for the first performance in Madrid [May 1975], we said: “Right, what shall we play?” We played, came off, went back on again and kept doing that. I don’t know how long we were on overall. In the end, we went up into the balcony and sat with the audience, seeing the responses while the lights were still down. Finally, the music ran out, probably 40 minutes later. Someone turned to his friend and said: “This is genius!” And the man next to him went: “This is shit!” Then there was some sort of altercation. On the second night in Barcelona, we were playing in a bullring. We came off once again and walked around the enclosure where the bullfighters would go. Eno opened the door, looked out and there were the audience, still wondering if it was over or not. This American saw us and asked if it was over. Eno said: “It is for us, but not for you”, then closed the door. Then at our first performance in France, the sound system didn’t work very well and there was a lot of crackling. After 20 minutes, the booing was as loud as the music coming from the PA. Eno turned to me, we nodded, pulled down the faders and left.

You’ve credited Eno with opening your eyes to the possibilities of what you could do with music, a breakthrough that you date to September 1972…

I’d met Eno in the office, because Roxy Music auditioned for King Crimson in 1970 and I turned them down. And I remain one of two people, [Crimson lyricist] Peter Sinfield being the other, who have heard Bryan Ferry singing 21st Century Schizoid Man and The Court Of The Crimson King. I knew Eno was going to succeed, but not with King Crimson. He was a lots-of-fun character, very wild, and invited me round to his apartment in Maida Vale. I took my guitar and pedal board, went into the next room and plugged in. He didn’t say what was happening, but to me it was obvious. I played for about 18 minutes, Brian wound it back and then I played over the top. Forty-five minutes later we had The Heavenly Music Corporation as it appears on (No Pussyfooting) [1973].

The record company made no secret of the fact they hated (No Pussyfooting)…

I was told later that, as a consequence of the album, Eno’s management decided he was ready to go solo. They thought he had a far more glittering commercial career available to him than working with the progressive-rock, left-field guitarist Robert Fripp, which now seems absurd. However, here are the ironies. David Bowie was a fan, I believe, of (No Pussyfooting). And I was told that Iggy Pop, who David was working with at the time, could sing all the main guitar themes to the album.

When did you first meet Bowie?

I’d met David in London in the spring of 1972 and saw the Rainbow show, when he was supported by Roxy Music. That was one of the best rock shows I’ve seen, just stunning.

Hadn’t he also been at King Crimson’s first show at the Speakeasy in 1969?

Yes. He got up to jive with Angie [Barnett, soon to become Mrs Bowie], but my attention was elsewhere. Various members of Yes also turned up. [Guitarist] Pete Banks had a drink that didn’t leave the bar throughout the first set. As a pal said to me later: “And if you knew Pete Banks, that was quite an achievement.” [Yes drummer] Bill Bruford came to our second show, when we played the Lyceum at four in the morning, supporting T. Rex. He returned to the other members of Yes and decided, so I was told, that they needed to practise more.

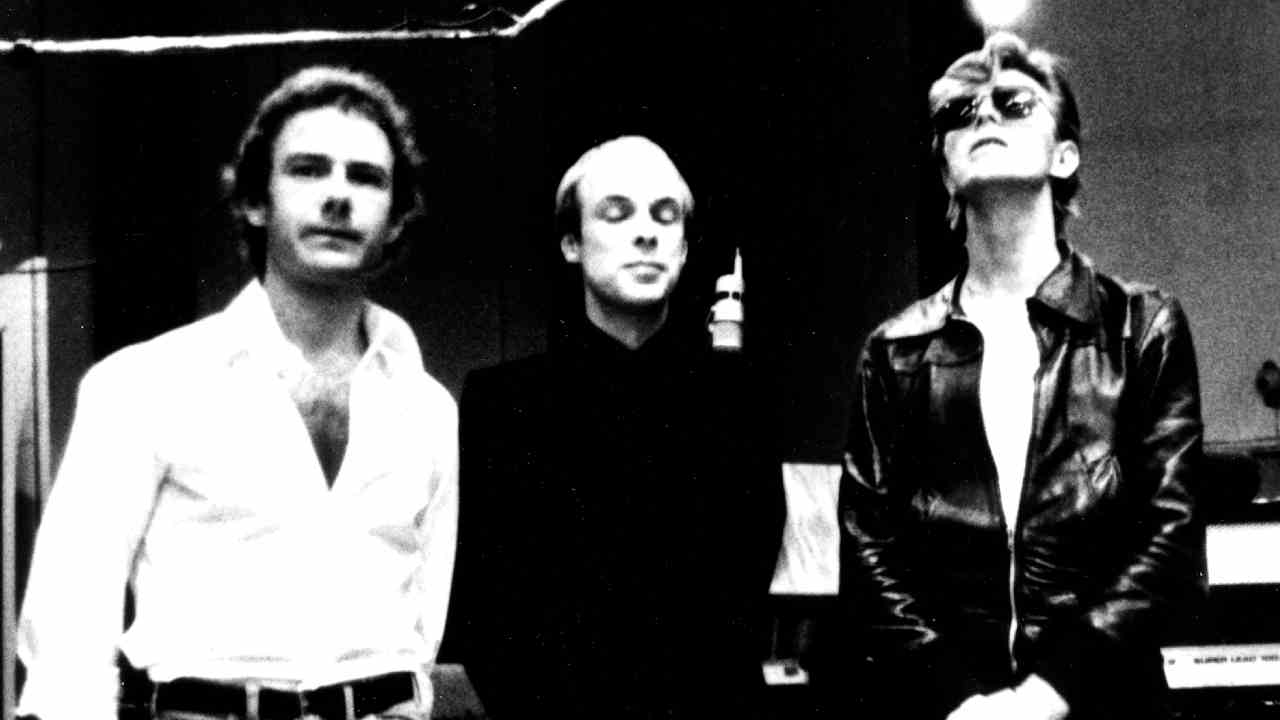

How did you come to play with Bowie on Heroes?

I got a phone call when I was living in New York, in July 1977. It was Brian Eno. He said that he and David were recording in Berlin and passed me over. David said: “Would you be interested in playing some hairy rock’n’roll guitar?” I said, “Well, I haven’t really played for three years, but if you’re prepared to take a risk, so will I.” Shortly afterwards, a first-class ticket on Lufthansa arrived.

And you worked with him again in 1980 on Scary Monsters…

We were doing either Up The Hill Backwards or It’s No Game and I said: “Any suggestions?” And David replied: “Ritchie Blackmore!” Because David isn’t really a guitarist, he couldn’t give me more of a ground plan than that, but I knew what he meant. One of the few guitar solos in King Crimson which I think is on a par with my work for Eno and Bowie is on Sailor’s Tale from the Islands album, in 1971. It has all the intensity, it’s terrifying stuff. I actually did at it three in the morning.

Have you always had an issue with King Crimson being labelled as prog?

Yes, it’s a prison. If you walk on stage and you’re playing music, fine. But if you’re walking on stage and you’re playing progressive rock: death. It began as underground rock, became art rock, then progressive rock. But, as a term, ‘prog’ only evolved in the 1990s. And I loathe it. As soon as someone sticks a label on to you, they stop listening. It’s very strange for me now, after 40-odd years, in that people are beginning to be nice about King Crimson. Back in the 70s, there was something astonishingly wrong with the music press when it came to King Crimson. The amount of hostility and sheer vitriol that was poured out, even lasting into the 90s. Some of it was so hilarious you couldn’t take it seriously. ‘Prog Rock Pond Scum Set To Bum You Out’ – that was the headline in the LA Reader when King Crimson played Los Angeles in 1995. The band loved it actually, we still wave that one about. But nevertheless, I think there was damage done. As a template for how a creative, evolving band-unit works, my models would always be jazz groups. Miles Davis, particularly. Let’s face it, Miles was progressive.

So why have people come to regard King Crimson in a better light now?

I know that I’m a man of a certain age, because people are kinder and more polite to me. And people don’t take you seriously anymore. You’re no longer a threat. You’re just a funny little old man, so they begin to be nice to you. They also ignore you at the same time, but there you are.

I believe you’ve been in the studio since the American tour, working on new Crimson songs…

It’s been going very well so far. We’ve also been mapping a release schedule for live material from the US tour, which we’re planning. But I won’t say too much at the moment. Let’s just say there’s a staggered, increasingly completist presentation planned. Let’s leave it there, shall we?

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 206, December 2014