“I remember that great morning when the term ‘classic rock’ was invented,” Robert Plant says, by way of introduction, at his base in the Severn Valley. “It became a radio network in America long before your magazine. What had happened was that the world of ‘raaaak’ – with several ‘a’s – had become like an oldies station.

"But it doesn’t relate to you guys much, because you’ve kept up with my madnesses over the years. And I appreciate that because, ironically, I don’t get played on classic raaaak these days, apart from my previous incarnation. Now I’m out there with the angels and the birdies, there’s not a chance in hell.”

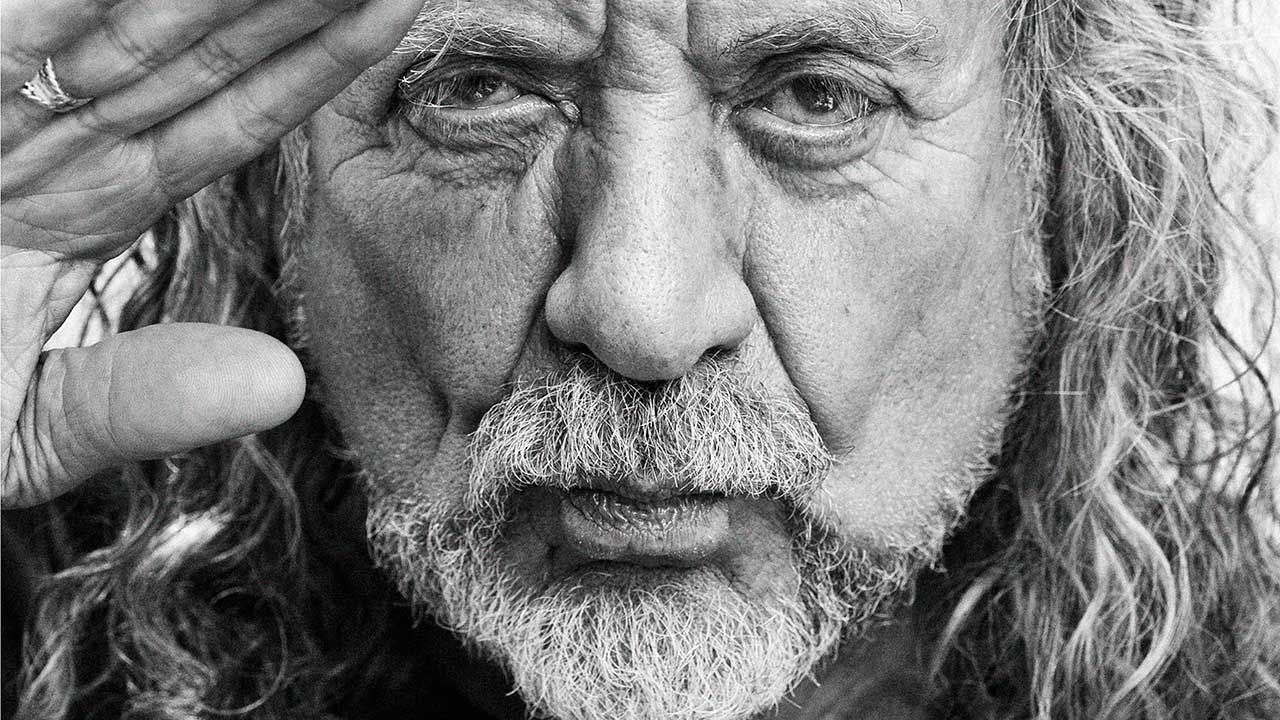

Plant has indeed been out there for some time now, ever since making his solo debut in 1982, two years after the death of his great friend John Bonham signalled the end of Led Zeppelin. It’s been a fascinating and wide-roaming career, pulling in elements of folk, blues, African music, psychedelia, roots-rock and beyond. And while he acknowledges that, for some, he will forever be the golden god of Zep legend, his rich catalogue – from his first tentative steps as a solo artist to the multi-faceted brilliance of recent albums Lullaby And…The Ceaseless Roar and Carry Fire – is the work of an inveterate seeker.

A conversation with Plant is just as digressive, his mind sparking off at tangents, one recollection eliding into another. Today he talks about his early years in Birmingham; being chauffeured around town by John Bonham at the height of his fame; bad-hair days on Top Of The Pops; why he’ll never write a memoir; his recent sojourn in Texas… And of course there’s his current band of brothers, the Sensational Space Shifters.

He also talks a lot about digging deep, which brings us to his latest endeavour. Digging Deep With Robert Plant is his hugely popular podcast, in which he eloquently discusses the hows and whys of songs from his across his career. Digging Deep is also the name to a box set that gathers together singles from his solo albums up to 2005’s Mighty Rearranger.

Plant is great company. And, considering that aforementioned “previous incarnation”, about as unstarry as it’s possible to be. Modest too. He and the Shifters are just back from America, where they ended their tour with an appearance at Hardly Strictly Bluegrass, an annual bash in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park.

“I’m still stoned from the weed in the crowd,” he laughs. “Fuckin’ hell! I was craving a snack by about song number three. What I wouldn’t have done for a tuna melt.”

It’s time to dig in...

What prompted you to do the podcast?

A lot of the endeavours that have been and gone since the passing of Led Zep have been great dalliances, almost like romances with different musicians and their input. Different sounds and the way contemporary recording changed in the mid-eighties, the fond farewell to analogue recording. All that sort of thing. I think I had so much experience of the acceleration of creativity going into chaos for a period in the seventies, that I really just wanted to keep doing different things all the time.

I do interviews with people and they say: “Have you thought about writing a book?” I go: “Fuck off. Everything that I’ve got between my ears, or between my legs, is my business and nobody else’s. I know too many things, and when I finally depart this mortal coil I don’t want my family to think that I was some kind of weirdo.” So I keep it hid. One of the tracks off my last record [2017’s Carry Fire] is about just that – Keep It Hid. And that’s what you have to do.

At the same time as guarding your privacy, the podcast aims to throw light on parts of your back catalogue.

Talking about the creation and development of music is a double-edged sword. I recently did a gig in Roskilde, Denmark, and Bob Dylan wanted to talk to me about touring. So I met him where all the buses are parked, at this big festival, and we eyeballed each other and smiled in the darkness. It was pissing with rain, two hooded creatures in a blacked-out car park, and I said to him: “Hey, man, you never stop!”

He looked at me, smiled and said: “What’s to stop for?” But I couldn’t ask him about his songs, because as much as I’ve been affected by his work you can’t talk about it. My work is not anywhere near as profound in what it’s trying to do. At the same time, you can get to know the motive and circumstances behind a particular song, without it being Masters Of War.

Through discussing certain songs on the podcast, have you discovered a unifying thread to your work?

In a way. There was always a reticence with stuff, kicking off in 1982 with Pictures At Eleven, which was using drum boxes and stuff, just trying to break the mould of expectation of me being part of some huge juggernaut. The bottom line is to dig deep. At the time, I kept on twisting and turning with these musical threads.

When I look back now, I never quite reached the point where I was trying to get to with some of them, but with other ones I really did. Doing Your Ma Said You Cried In Your Sleep Last Night [a cover of Kenny Dino’s early-60s hit, on 1990’s Manic Nirvana] with the actual run-in to the track being the sound of the stylus on the original vinyl in my house was just idiosyncratic beyond all belief. Nobody gave a flying fuck. But I did. And that’s what counted.

The whole idea of doing this thing is that it brings these songs back to life, which is fun. They almost come to life in a totally different way. It’s amazing how the whole idea of podcasts, as a mode of entertainment, has replaced radio in many people’s imaginations.

I’ve also got forty-plus tracks that I’ve never put out. I’ve got stuff that I did in New Orleans with the Li’l Band O’ Gold and Allen Toussaint. I’ve done so many things. I’ve got a whole album, Band Of Joy II, that I did with Buddy Miller and Patty Griffin. I’ve got stuff everywhere. So it might be a good way to gather some pretty powerful stuff and just eke it out there. I’ve just been tidying up my little studio here, to do some rehearsing later in the week, and found some stuff with the Space Shifters that we did at Rockfield two years ago. So it’s not just about stuff that came out through the normal channels.

Going back to the start of your solo career, am I right in saying that it almost didn’t happen? You were all set to go to teacher training college at one point.

In 1977 we lost our son, Karac [he died of a stomach virus while Led Zeppelin were on tour in America]. He was only five years old. I’d spent so much time trying to be a decent dad, but at the same time I was really attracted to what I was doing in Zeppelin.

So when he bowed out, I just thought: “What’s it all worth? What’s that all about? Would it have been any different if I was there, if I’d been around?” So I was thinking about the merit of my life at that time, and whether or not I needed to put a lot more into the reality of the people that I loved and cared for – my daughter and my family generally. So yeah, I was ready to jack it in, until Bonzo came along.

He convinced you otherwise?

Yeah. He had a six-door Mercedes limousine and it came with a chauffeur driver’s hat. We lived five or six miles apart, not far from here, and sometimes we’d go out for a drink. He’d put the chauffeur driver’s hat on and I’d sit in the back of this stretch Mercedes and we’d go out on the lash. Then he’d put his hat back on and drive me home.

Of course, he’d be three sheets to the wind, and we’d go past cops and they’d go: “There’s another poor fucker working for the rich!” But he was very supportive at that time, with his wife and the kids. So I did go back [to Zeppelin] for one more flurry.

Similarly, a few years later, Phil Collins helped you on your way when you went solo.

Phil was at such a huge peak and very prolific. I sat in a room with Atlantic Records and Peter Grant, talking about the solo thing. I said: “Look, there’s no other way to do this, really. I’ve got to keep going, because I’m thirty-two years old and I haven’t actually felt anything else other than this juggernaut success thing. I need to find out what the other side of it is like.”

Consequently, Phil Carson, of Atlantic, was dealing with Phil Collins’s solo stuff, post-Genesis. Phil was such a huge fan of John [Bonham] that he sent me a message: “I’d really like to help you, because this must be one of the toughest things you’ve ever had to do, musically.”

He was talking about me being without the guy I’d been playing with since I was sixteen, although we had a fiery relationship, myself and Bonzo. So Phil came in and just got on with it. We had four days for the first album and four for the next. So we were cutting backing tracks non-stop. And if he didn’t like something, he’d stop halfway through, stand up and tell people why it wasn’t quite right. I loved that, because I was still tiptoeing around, not knowing how to deal with other musicians.

As much as there was trepidation about going solo, presumably it was also a liberating experience?

Absolutely. It’s really what it’s all about. You’ve got this thing inside you where you know there’s something around the corner that you’ve never heard before, but who’s going to pick the lock to get it out? I knew [guitarist] Robbie Blunt really well, from being around this area here in North Worcestershire. He’s a very lyrical guitarist, a beautiful player.

So I hear the first solo record and things like Like I’ve Never Been Gone and realise just how beautiful his playing was.

Like I’ve Never Been Gone is on the podcast and in the box set, as is 1983’s Big Log, your first major solo hit. Looking back at your performance of it on Top Of The Pops, you seem slightly awkward.

Well, I don’t know who the hairdresser was. I’m still looking for him. He’s probably hiding somewhere. The song is a good one, but I felt out of place with the whole deal. I could understand more the Robert that had played at the Fillmore in San Francisco, with everybody flat out on the dance floor while we [Led Zep] were doing a song that lasted fifteen minutes, with a violin bow in the middle.

Singing a song that had a beginning and an end, at that point in time, was quite challenging. And also miming. It was all so new. It was a long way from playing with Alexis Korner in some folk club.

You once said you felt you were “in the wrong place” around the time of Big Log. Can you expand on that?

I didn’t really know what to do, because the wheels of fortune – and also the wheels of Warner Bros. – were encouraging me to play it tough and hard and to somehow carry on the tradition that was already there in the psyche of everybody, because of the Zeppelin thing. And I think I touched on that with things like Slow Dancer [from 1982’s Pictures At Eleven]. But the idea of actually being groomed into this other guy was very odd.

I made a few videos and I got on maximum rotation on MTV, which was kind of funny. We all grow, you know? It’s either that or recede back into something and say: “I’ve gone far enough now and this is all I can do.” I think the growing went from that MTV rotation thing into slowly edging my way out into Fate of Nations [1993]. From then on I was kind of gone.

You’ve described Fate Of Nations as a turning point. Was that the first time you really felt comfortable as a solo artist?

Not really. If it was about being comfortable, there wouldn’t be any point in being creative. I just needed to keep good company and, bit by bit, I made my way into that. I was able to work with people who I have huge respect for, like Richard Thompson, and then move into a zone where, ultimately, I was making records with T Bone Burnett and Alison Krauss [2007’s Raising Sand].

So you grow into the person that you didn’t know you were going to be. Or else you do a rock package. Or even a fucking boat! So I don’t think I was ever really comfortable with the whole idea of doing Top Of The Pops. I found myself developing into this other guy instead – not complacent, but I definitely had a groove.

1988’s Tall Cool One samples Led Zep and features Jimmy Page on guitar. Had you started to make peace with your past by then?

The Beastie Boys had started sampling Zeppelin [on She’s Crafty, which samples The Ocean]. I thought: “That’s a great idea. Listen to that.” Because you can take it out of context and bring it into another zone, which is exactly what we did with Tall Cool One. We took lots of different bits of Zeppelin.

I thought it was slightly comical as well. Even the title, Tall Cool One, was an instrumental by The Wailers out of Seattle in 1959. So there was nothing new there, it was just a kind of visit. But coming to terms with the past, no no no. I mean, which past shall I go to?

But in the podcast you stress how mindful you were of not turning into that Led Zep parody guy.

Yeah, but no matter what happens, I have no choice. There have been great variants of another me, but whenever I read a newspaper it seems I’m still in Led Zep. I think the problem is that nobody can hear what artists who stick around are able to put out now. If you don’t go out and find it by your own volition, it’s not going to come down the normal channels. And I think a lot of people who go to gigs don’t even listen to the radio. So do you go to Spotify and see it there: “Robert Plant has made a new record, has he? Fancy that!”

On 2001’s Dreamland you cover Bonnie Dobson’s apocalyptic folk song, Morning Dew. How did you come to that one?

I heard it when Tim Rose had a kind of hit with it in sixty-seven or sixty-eight. Later on in that period of the Morning Dew era, John Bonham was the drummer in Tim’s band. I had to go and fish him out for Jimmy [Page] from the Hampstead Country Club, when he was playing with Tim. I never even realised it wasn’t Tim Rose’s song.

He did a deal with Bonnie Dobson, who’s since become a regular acquaintance of mine whenever we go into Bert Jansch world. I just thought that song was really beautiful. It would be just as valid for that to be played now by a really contemporary artist. Just change the time signature. Let kids hear it and realise that we’re in trouble.

Going back to your own folk club days around Birmingham in the sixties, was it a healthy scene?

It depends where folk and blues become two different things. I would say that Alexis Korner singing Rock Me Baby may not be traditional English folk, but it can still run in the same climate. The folk thing was only really in the very early days for me.

It was a very prolific scene around where I was at school, and there was a folk club there that had Alex Campbell, Ian Campbell and various people coming through who were singing songs about ships going down the Northumbrian coast or wherever it was. But the blues scene was more evocative for me, because it had that sort of minor-key, blue-note misery thing going on, which I love.

Did you take the usual route to music via doing a succession of workaday jobs?

I was working at Lewis’s in Birmingham, measuring gentlemen’s inside legs. The great phrase that went with that task was: “Which side do you dress, sir?” In other words, where are your bollocks? And if those guys were a little bit springy, they’d tell you the wrong side, just so you would give it a quick tweak!

I believe your dad played violin, but did your parents still have that attitude of: “Go and get a proper job”?

Well, I was bound for a proper job, and I’ve got one. Yeah, I had my moment of professional potential, and because I didn’t accept it I had to leave home when I was seventeen. So I toughened up pretty quickly. I made my peace with my parents a couple of years later. But it was good, it was what it should be.

I know so many guys from my time at school, who I still see and who are very funny and love life, but they did the wrong thing. They stuck with a family or whatever you were supposed to be doing, and they really rue the fact that it never really kicked in. They didn’t live their life, they lived the life that was required.

So you knew early on that you didn’t want to do that?

I didn’t know what I wanted to be, but I wasn’t going to push a pen for two quid a week and train to be an accountant.

Pre-Zeppelin, you and John Bonham played in Band Of Joy around the Midlands. But is it fair to say that at that time your spiritual home was the West Coast of America?

Yeah, I think so. It was more like there was something being said there. We didn’t have the Vietnam phenomena and we didn’t really have the same knee-jerk racial tension – although there was racial tension, but we didn’t have the marches. The whole deal of being over here was old Empire.

America has always been reeling and yawning and growling and having internal conflict, so the youth culture was dealing with its own problems. So on the West Coast, the people out there were vanguards for their own generation of musicians, bringing it through. If you think of Buffalo Springfield’s For What It’s Worth, it’s all about what they were dealing with themselves on the street with the authorities. Over here, the revolution was slightly to suit a bit of a cottage industry; there were a lot of bells and beads and stuff being sold.

Leaping forward to your 2005 album Mighty Rearranger, you talk about one of its songs, Tin Pan Valley, on the podcast and how important that time was on a personal level. You suggest that it was the start of you embracing that challenge of being both a singer and songwriter in earnest.

Maybe, but I’ve always been trying to make the whole thing work as a kind of rounded-off piece. I think the great power of Mighty Rearranger is its flexibility, from Tacamba [a Malian rhythm] through to all sorts of things.

Nine years later, Lullaby And… The Ceaseless Roar seems to be the culmination of all that searching and experimenting.

We got rid of the kind of grit and aggression of a recording like Tin Pan Valley, and replaced it with the panoramic drama of Embrace Another Fall, which is a combination of musicality and intention and poetry that I could never have imagined way back when.

Lullaby is all rhythms and texture, with your voice as part of that “panoramic drama”. Was that a breakthrough of sorts for you?

It’s partly to do with circumstance. Sometimes you don’t run your own life, it runs itself. I saw my life opening up in a different way. I suppose if I go back to Mighty Rearranger and move from thereon through, there was a whole deal of fantastic opportunities and changes which I could try to get into and stagger through, which I did.

So from Raising Sand to Band Of Joy [the 2010 incarnation], these were really quintessential moments for me, because I was just really a singer from the Black Country who did a good version of Rock Me Baby, and I’m suddenly in all these different environments, musically and emotionally. And I was convinced, the more I travelled through America and the more people I met from different parts of the musical globe out there, that that’s where I should be.

During the Band Of Joy era [2010-11], I spent a lot of time with Patty [Griffin] while she was living in Austin, Texas. Of course I’d been travelling through America for forty years or so, and I’d always seen these little postcard visions of various places. But I’d never actually lived in it to see what it really was. So I moved to Austin. And I was surrounded by some incredible musicians. Jimmie Vaughan, Stevie Ray’s brother from the Fabulous Thunderbirds, was a great player. Charlie Sexton, Junior Brown, Wanda Jackson… so many people. And I was part of that fraternity of great players coming and going, moving in, moving out.

The bottom line is that I really embraced the whole idea of being in that scene and I was living alongside Patty. And she’s so prolific and such a soulful cat that I thought, this is it. This is the whole deal of what it’s all about – musical integrity, great company and stimulus. And a really warm welcome from people from all the arts. So I dug deep into it and bought a place there. But then I kept on looking back home and wondering how it was with my kids and my mates.

I relish the simplicity of life sometimes. I was really getting used to the fact that I was switched on in Texas, but there was no escaping my story. So I couldn’t take it any more and came back. And that’s what Lullaby And…The Ceaseless Roar is all about. It’s about coming back, about failing, really. Or actually just realising that it takes so many different elements to make a life.

The whole of that record is about realisation, about maturity, about trying to get in line with yourself and finding out that you sold yourself down the line a little bit. And in its own way, that’s the blues.

Your most recent studio album, 2017’s Carry Fire, feels like a companion piece to Lullaby.

Yeah. The Space Shifters, to a man, are remarkable. They’re also remarkable from the different angles from which they’ve developed. Justin Adams and Johnny Baggott and I have been together, on and off, since 2001. And there’s enough going on in between that when we come back it’s a great homecoming.

When Billy Fuller arrived, he brought something different again from his side. And he’s got his adventures with Beak. John Blease has joined us on drums. He’s an amazing player. And ‘Skin’ Tyson was a founder member of Cast. So it’s like a kind of fraternity. We can get together any time and it’s all good. There’s great creative encouragement between us all.

Do you have anything new on the horizon, recording-wise?

Yeah, there are some things in the air, possibly in Nashville. I’m supposed to be going there in two weeks’ time. There’s nothing going on at all at the moment, but there will be. Between Justin and Skin and everybody, we’ve got about forty different instrumental ideas already. We work with a guy called Tim Oliver, who’s the studio manager down at Real World, Peter Gabriel’s place, and we can mess about in there.

I can spend an afternoon with Tim and really shift styles and stems of music in preparation to shape them as songs. We’ve recorded the last two records with Tim and it’s a great way of doing things. It’s a good combination. We all know where we’re going.

Will there be a follow-up to Raising Sand at some point?

Oh, I’m sure, yeah. I see Alison a lot and talk to her a lot. And T Bone too. The reality is that I ran back once before, and Patty had made her American Kid record [2013] and was touring with that. And I think once you start splintering off and going different ways, and you’re a stranger in a place where people still think there’s a mirror ball rotating around your head, it’s really good to dig in with the reality of the Space Shifters. There’s no greater thing than being on stage when these guys are in full flight.

Pete Townshend recently said he thought guitar-based rock’n’roll had exhausted its possibilities, and that new technology has opened the door to create other forms of music with different attitudes and ways of working. What’s your take on that?

I just think that the game is there for everybody and everything. As far as the people on the street are concerned, it’s just a matter of taste. There are people making great music everywhere, all the time. Pete’s right in that as far as recording techniques and changing the whole idea of creating songs goes, you don’t have to worry about a guitar solo.

You can put in lots of little bits of confectionery in contemporary stuff. And humour and social commentary. Not everything has to come from Nashville. I think that’s just the way that Pete feels. Also, he’s been travelling a lot, so he’s probably switched on to all sorts of musical formats.

One of the things that you refute in the podcast is the idea that you’re restless. Instead you say it’s more a case of you being inspired and constantly stimulated.

It’s another way of looking at the same condition, isn’t it? It’s the same beast. I don’t know when the curtain’s going to close for me, either as somebody who’s inspired or as somebody who’s actually breathing, but five-a-side on a Wednesday night is not enough.

So I do this. And I’m lucky, because I’ve got two or three different roads that I can enjoy with people, and different rewards. I do know that bona-fide bands put out records and tend to feel disappointed. Because the whole window of exposure and opportunity has gone, no matter whether it’s Neil Young, Elton John or whoever it may be that people are ready to switch on to.

But who cares? If it’s fucking hip-hop or a cover of a Melanie song, it doesn’t matter. Just do what you do and feel it and mean it.

Robert Plant’s Digging Deep box set is out now.